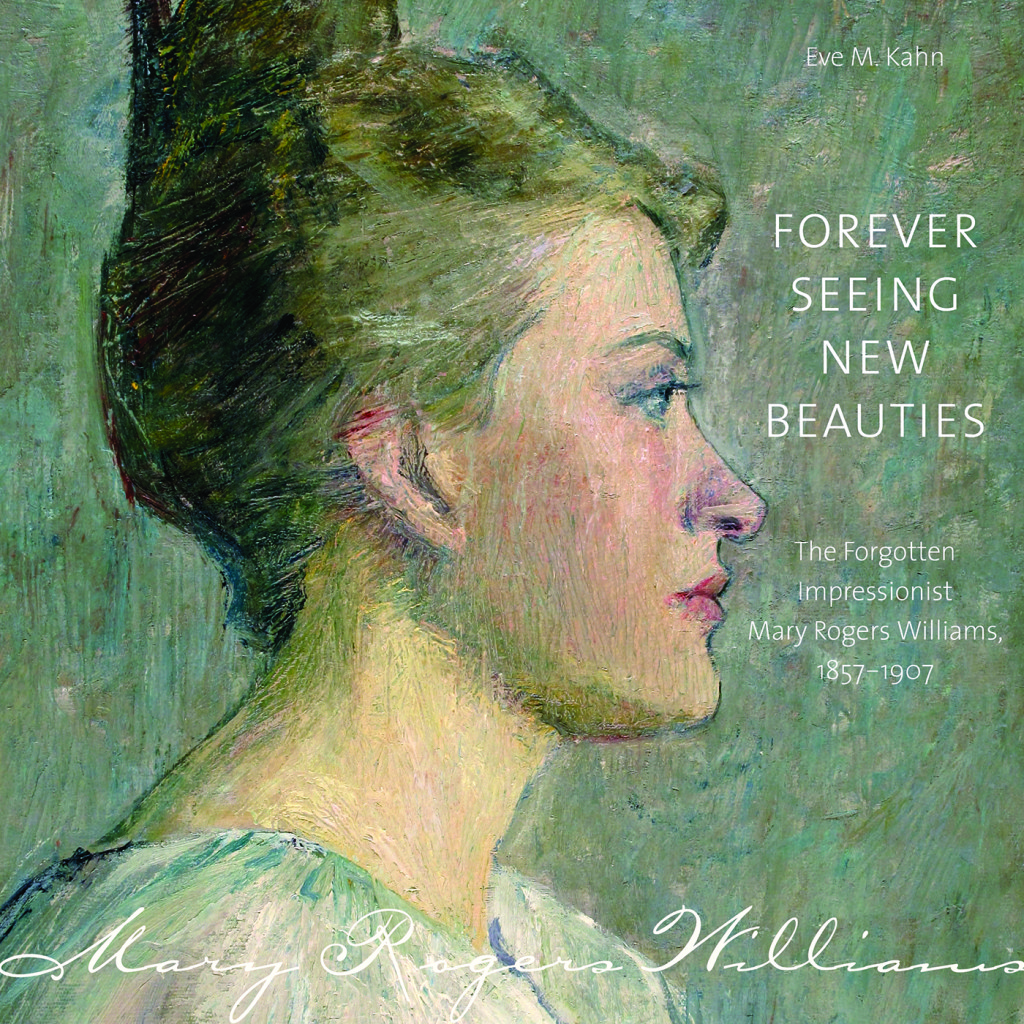

From the arresting first words of her new book Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857-1907, forthcoming from Wesleyan University Press, journalist and scholar Eve M. Kahn is a persuasive spokesman for the long-overlooked artist, diarist and feminist who blazed trails in the United States and Europe even as she endured the condescension of her male colleagues. Building on letters, lively in their narrative detail, from the Hartford-born painter and pastelist to her friend and colleague Henry Cooke White (1861–1952) of Waterford, Conn., Kahn uses Williams’ own incisive observations to pen a compelling biography rich in period detail.

What are the most important things to know about Mary Rogers Williams?

She crisscrossed Europe from Naples to Norway while painting in a foresightedly Modernist manner and sent home vivid and witty letters about her adventures and emotions that no one has read in a century.

How exceptional is she for her time and place?

Few other painters of any era can be documented this clearly day-by-day, and few women of her time — let alone on a modest schoolteacher’s budget like hers — traveled so widely on their own steam. She had some impressive art-world successes — exhibiting dozens of times, from Paris to Indianapolis — although the field was heavily loaded against women. And although I’m sure she didn’t intend her letters to be published someday, they offer a hilarious feminist take on the pomposity of men in power.

You describe the thrill you felt upon opening a box of Mary’s letters for the first time. When did you know you had a book?

For decades I’d been writing newspaper and magazine articles, regular columns and the occasional book essay. People would always ask, ‘When are you going to write a book?’ And I’d answer, jokingly, ‘Oh, only when I find some forgotten trove of important material that no one has seen before.’ Mary found me. Before I knew it, I was meeting with Wesleyan University Press.

Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857–1907 by Eve M. Kahn will be available in early November in both hardcover and eBook editions from Wesleyan University Press.

You have a great eye and ear for the telling details of Mary’s life. How did you settle on your narrative approach and tone?

The tone, the narration, the vivid detail — that’s Mary’s doing! She wrote with no nonsense, very minimal philosophizing, no pretensions or self-aggrandizing, no lies that don’t jibe with other sources.

Tell us more about your sources. You clearly spent much time mining archives.

I pored through any papers I could find for anyone who knew Mary. There were mentions of her or her family scattered in files at Smith College, Connecticut Historical Society, New York Public Library and Yale. I called and emailed everyone I could find descended from her relatives or anyone who knew her. Most of the time my outreach was a bust, but there were people who replied with something great.

As Mary describes them, Dwight Tryon (1849-1925), her boss at Smith College, is monstrous and James McNeil Whistler (1834-1903) is something of a fool. Do Mary’s first-hand observations about other artists alter what we knew about them?

Some scholars I spoke to who had looked at Tryon’s papers in depth said, basically, honestly, well, they thought he was kind of a jerk, too. Whistler’s foppishness and self-absorption, that’s been written about somewhat. I’m just so happy to have added Mary’s evolving perspective — that she adored Whistler when she first met him in London and then later became amusedly appalled in Paris as women fawned over him during rather useless, expensive classes. I think I convey what it was like to be at the edges of the Victorian art world as Modernism crept in and women gained some footholds.

Monhegan Island in Maine inspired some of Mary’s loosest artworks during a 1903 trip. Pastel, 4¼ by 5¾ inches. Private collection, Ted Hendrickson photo.

How much work remains to be done on women artists?

I can hardly believe, in the seven years since I went down the Mary rabbit-hole, how big a wave of deserved homage is being paid to under-appreciated dead women artists. Group shows, solo shows, monographs, museums announcing acquisitions with fanfare, even selling work by men to buy women’s stuff. Take Hilma af Klint’s show at the Guggenheim. I went back again and again and it was never not packed with amazed people.

Will your book be the basis for related projects in different media?

I’ve got lectures coming up: October 6 at the historical society in Portland, Conn. — that’s near where Mary painted at her family’s ancestral farm — and October 27 at the Boston International Fine Art Show. And if anyone is interested in Mary’s movie rights, I’m in. It’s evemkahn@gmail.com.

What’s next for you?

Well, I thought I’d never write another book after this labor of love. But a few months ago I excavated archival material for another under-appreciated circa 1900 woman innovator, the journalist, fiction writer and magazine publisher Zoe Anderson Norris (1860-1914), who documented New York immigrant life and was known as the Queen of Bohemia.

—Laura Beach