Americans are increasingly discovering their ancestral connections – as evidenced by the popularity of DNA services like Ancestry.com and 23andme and television programs like Finding Your Roots. Against this social trend, biographer Grant Hayter-Menzies contributes a unique memoir woven from a rich family history full of faces, personalities and compelling stories. Following the threads of lore, remembrance and facts, he has written The North Door: Echoes of Slavery in a New England Family, based on his search for the truth about his slaveholding ancestors and personal encounter with descendants of people they enslaved, not just in the South but in the North.

Your slave-owner ancestor, Benajah Bushnell from Norwich, Conn., held Guy Drock, a young man of Cameroonian origin, in bondage starting in 1730. Did your research cause you to change your perceptions about life in early New England?

I’d only known New England as the crucible of abolition. When I found that most of my New England ancestors had held people in slavery, including Guy, from the early 1600s until the 1780s, I had to reorient my whole view, confront the complexity of a history I was never taught and barely knew about New England. And I wanted to know more.

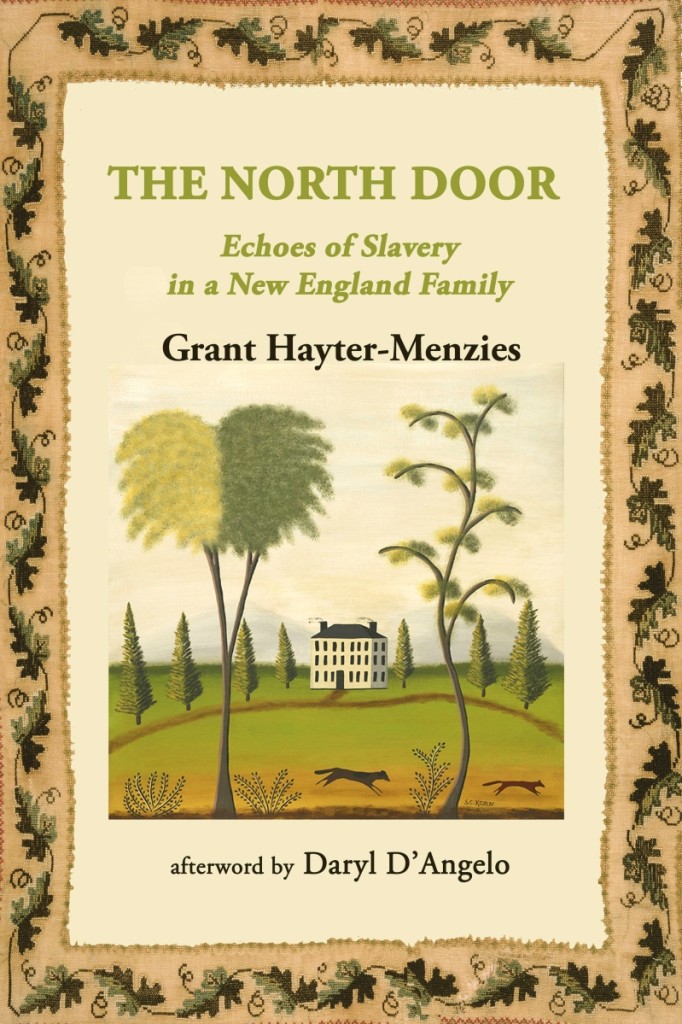

The cover of your book features a landscape by Massachusetts artist Suzanne Carroll Korn, who has researched and written about Nineteenth Century painted-decorated plaster walls in New England for more than 20 years. Why was her art chosen for this project?

I’ve called my abiding vision of New England stereotyped, and it was: little square Greek Revival farmhouses stitched on samplers, with floral borders and edifying aphorisms. I wanted the cover of the book to offer a suggestion of that naiveté and, perhaps, the naiveté of people who can’t or won’t accept that slavery existed in New England. I also chose Suzanne’s painting because in its purity and honesty it speaks to a key facet of America that has never died, which we need to reclaim.

After writing this, have you been able to overcome rightful anger toward the Bushnells and guilt about your other slave-owning ancestors?

I realize that none of these historical crimes were committed by me. But I can’t not feel compassion for the people my ancestors enslaved and share my grandmother’s concern about what happened to them after they were freed, not to mention the lasting effects of that brutality on the descendants of those people and on American society in general today. America still has far to go to acknowledge this debt to the enslaved and to their descendants and to making them whole.

Talk a bit about your work with Greenwich Historical Society president Debra Mecky and the Slave Dwelling Project at Bush-Holley House.

Years ago, I envisioned meeting descendants of people my Southern ancestors had enslaved. I’d offer my apologies to their ancestors through them, compelling my own ancestors to reach out a hand along with mine to these people whose ancestors they abused. I met those descendants not in the Deep South but in Connecticut, adding layers to the complexity. Not only that, I was able to convince the Greenwich Historical Society and Bush-Holley House, with its publicly interpreted former slave quarters, to allow the Slave Dwelling Project (SDP) to spend a night in that cramped space over the kitchen. SDP was founded by Joseph McGill, a descendant of enslaved Southern blacks, to address neglect of plantation slave quarters in the South. Too often guides tout the Big House for tourist dollars and ignore the slave cabins – the inconvenient engines of an enslaver family’s wealth. Joe draws attention to these dwellings by spending a night, then blogging about the experience. Meeting descendants of Guy Drock, the African man enslaved by my Bushnell ancestors, and spending a night in the slave quarters of Bush-Holley House with Joe, allowed me to confront my personal history as well as American history. I wasn’t sure Guy’s descendants would want to take my hand, and I wouldn’t blame them, nor was I sure Joe would want me in the quarters with him. By welcoming me, they changed my life, and this book was born.

You’re a long way from Connecticut today. What drew you to Victoria, British Columbia?

I married a Canadian in 2005 and moved here to join him, taking Canadian citizenship in 2010. There are issues around race here that need much work, but there is much to be grateful for, including the fact a black woman, Viola Desmond, Canada’s Rosa Parks, was just honored on our $10 bill. I feel good living in a country where government and people are trying and often succeeding to follow the better angels we all have, if we’d just listen and act on conscience’s advice.

Click Here to purchase the e-book version of The North Door: Echoes of Slavery in a New England Family.

-W.A. Demers