After a comprehensive search, the board of the National Academy of Design (NAD) recently selected Gregory Wessner as the institution’s new executive director. The appointment marks the latest milestone in the NAD’s revitalization, following the creation of an endowment that provides financial stability, and a renewed commitment to the academy’s diverse constituency. The 195-year-old academy was first formed to promote American art and architecture, and that same tradition lives on today, adapted for the Twenty-First Century. Among its community of National Academicians, the institution counts 431 living artists and architects and 2,372 National Academicians in total. Wessner begins his role there on September 8, so we thought this would be a good opportunity to sit down with him and learn what’s in store for the National Academy of Design as it approaches its bicentennial.

Congratulations on your new position. What is job one for you as you begin your role?

Such a hard question to start with! I don’t know where to begin. The National Academy has had some challenges over the past decade or so, which have been well documented, but it has pushed through those and is in such a strong position now. It is a moment of incredible possibility, and I feel so lucky to be a part of it. What I am really looking forward to is working with the board, and the National Academicians, to rethink programming and exhibitions, and beyond that, to determine what the permanent home for the National Academy will be. I think the board’s decision to sell the buildings on Fifth Avenue was absolutely the right one, and not just for financial reasons. The NAD is now free to rethink the kind of space it needs to best serve its community of artists and architects and to expand the kinds of programming it delivers. I know I am biased, but I have never been more confident in an institution’s future than I am about the National Academy right now.

This is a return gig of sorts for you, no?

That’s true – I was the administrator of the School of Fine Arts back in the late 1990s. I had been working at the Parrish Art Museum when Annette Blaugrund curated The Tenth Street Studio Building exhibition that opened at the Parrish and then traveled to the National Academy. Annette became the NAD’s director during that time, and then she hired me to work at the school. Having that prior history is so helpful because it allows me to better understand what this moment means in the larger trajectory of the academy’s history.

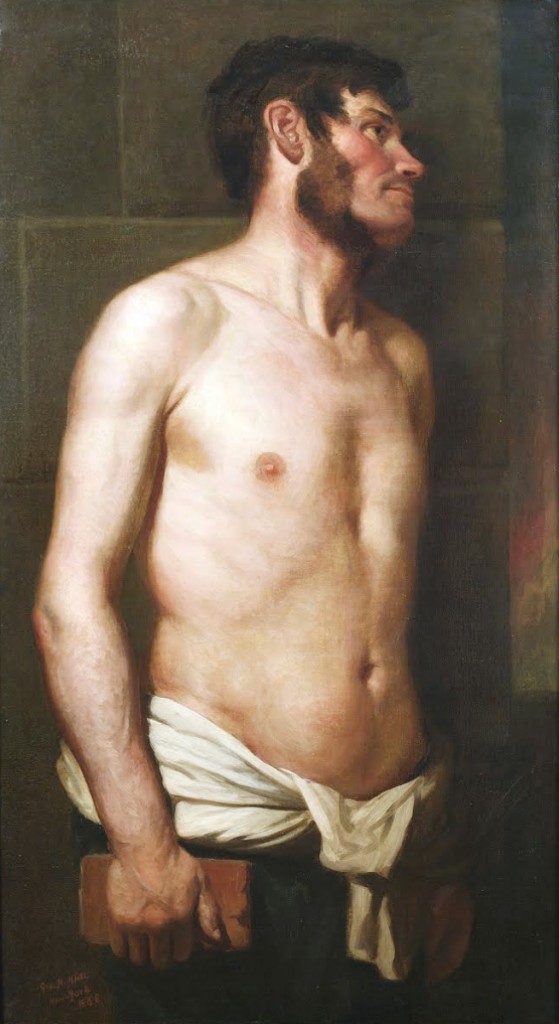

George Henry Hall, “A Dead Rabbit,” 1858, oil on canvas. 43 by 24 inches. NA diploma exchange presentation, April 3, 1882. Courtesy National Academy of Design.

The NAD holds one of the United States’ largest public American art collections. How many works have been donated by Academicians over its history?

The collection has more than 8,000 works in it, spanning painting, sculpture, drawing, architectural models, digital media and more. And, as I think everyone knows, what makes the academy’s collection so unique is that it has been assembled almost entirely through gifts by the Academicians themselves, as part of their induction as members. That makes it a very personal, and at times idiosyncratic reflection of how the artist and architect members want to represent themselves and their work. It is an incomparable collection of American art and architecture, and I think all of us at the Academy are eager to find new ways to make it more publicly accessible.

What did you do as executive director at Open House New York?

Open House New York is a nonprofit arts organization dedicated to public education about architecture, planning and development in New York City. When I started, its primary activity was the annual OHNY Weekend, a two-day festival every October that opens hundreds of architecturally and culturally significant buildings for tours and talks. The audience for that event had grown substantially over the years and it seemed to me like there was an opportunity to engage the public beyond just that one event. A big focus of my work there as executive director was to first envision a broader mandate for its programming and then to build the organization to be able to deliver it. New York has experienced rampant new development over the past decade, a lot of it not very good, so it seemed to me that Open House had a role to play to help the public better understand how the city was changing so that they could then help shape it in better ways. I was responsible for developing the program, as well as fundraising and board development, and all the things that nonprofits typically need to do. It has been one of the best experiences of my life, and I don’t know that I would have left for any opportunity other than this one at the National Academy of Design.

Tell us about OHNY Weekend and what you did to promote it.

I oversaw seven OHNY Weekends as executive director, and I am still sort of in awe at the scale of the event and, frankly, that it happens at all. We would open 275-300 buildings across all five boroughs of New York – many of which are never opened to the public – with help from a team of 1,500 volunteers and attended by about 85,000 visitors. It was by far the most logistically complex project I ever worked on, but at the same time, one of the most rewarding. It brought together an incredible mix of people – New Yorkers as well as visitors from around the world – for a shared experience of the city. An open house by definition is an act of generosity – you open your home or office or studio and welcome people to visit. Imagine applying that concept to an entire city – it is an extraordinary event, a chance to explore the city, meet new people, and learn about how others live and work. Not to overstate it, but it is democracy and civil society at its absolute best, which is something we need a lot more of right now. All that said, it is an exhausting event to produce, so I am excited to now experience it as a visitor!

Installation image of the NAD’s traveling exhibition “For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design” as presented at The Society of the Four Arts in Palm Beach, Fla., 2020. Photo by Christopher Fay. Courtesy National Academy of Design.

You’re not an architect, yet this summer you received the American Institute of Architects New York’s Award of Merit, its highest honor. What was that like?

It was a huge honor for me. The AIANY’s Award of Merit is the highest award the members give to a non-architect. I never expected to receive any award for my work, so when I got the call I was genuinely overwhelmed by the recognition. As you say, I’m not an architect, I’m not an artist. I see my career as being completely in service to artists and architects, creating opportunities for communicating their work and ideas to a broad public, whether that’s through exhibitions or lectures or whatever. So for them to recognize me in that way – it means more to me than I can say. It is without a doubt one of the high points of my career.

Do you see a resurgence of cultural advocacy on the national horizon?

Absolutely, and there needs to be even more. I think the arts, and artists, have an important role to play in helping lead us forward, asking questions about what kind of society we want to live in. As difficult as things seem right now, I have hope that positive change can come out of this. I think the critical questioning that is happening around how our society works, and for whom, is necessary and needs to be ongoing. And artists, and arts institutions, need to be a part of that.

The current administration grabbed some headlines earlier this year when it drafted an executive order that would give precedence to classical architectural forms in the construction of federal buildings. Your thoughts?

It is an absolutely horrible idea. And not because I have anything against classical architecture, of course – I love classical buildings as much as anyone. One article I read about this referenced what Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote in 1962 in his principles for federal architecture: that “an official style should be avoided,” and design must flow “from the architectural profession to the Government, and not vice versa.” I’ll leave it at that, because I don’t know how much more forcefully I can express my objections to this order.

In the good old days (like last year), we would connect with art mainly by visiting a museum. Do you believe that the pandemic has fundamentally changed the dynamics of buildings, galleries and the art that is shown inside them?

Do I think it will fundamentally change how we connect with art – in the long run, no. Nothing will replace the experience of seeing a painting or a building in person. And that will resume one day – I don’t know when, but it will resume. Will there be long term implications for how we design galleries and museums, or really any building, that responds to lessons learned during this pandemic? I would assume so. The history of architecture – and the history of cities – is defined in large part by how we adapted to public health needs and concerns. But how we experience art and culture is certainly changing in the near term, as we continue to adhere to stay-at-home orders and reduced capacities at museums and galleries. Thus, the proliferation of digital programming. For example, the National Academy is exploring forward-looking educational programs that respond not only to our current moment, but also anticipate the future of audience engagement. One series, which we will launch this spring, will be a digital platform devoted to creatively telling the stories of our National Academicians – the intersections of their personal histories and creative practices.

May Stevens, “Benny Andrew, the Artist, and Big Daddy Paper Doll,” 1976, acrylic on canvas. 60 by 60 inches. NA diploma presentation, May 19, 2004. Courtesy NationalAcademy of Design.

The traveling exhibition, “For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design,” is hitting all the major stops at venues across the United States through January 2022. Is there any work in the show that speaks to personally?

I can’t tell you how much I am looking forward to the day when we can travel safely again, because I haven’t even seen the exhibition yet, and I am really look forward to that. This is always a hard question because there are so many great works in the show. I love May Stevens’ “Benny Andrews, the Artist, and Big Daddy Paper Doll” for a lot of reasons, but especially because it captures a moment in her studio with a fellow National Academician, at a time in New York that was so alive with art and ideas and activism. There are just so many layers to appreciate in that painting.

For something completely different, I love George Henry Hall’s “A Dead Rabbit.” It is a pretty stunning painting; Hall depicts the man’s torso in such a frank way it is almost startling. Catherine Opie wrote a great piece for the catalog – the catalog, by the way, is a beautifully designed book, you should definitely take a look if you haven’t – in which she talks about the “tenderness and vulnerability of the flesh.” This is one of those surprises that you can find in the NAD’s collection.

COVID question, sorry. When you assume your new position on September 8, will you be going to the office or working from home?

Good question. I hope I can go to the office, at least a few days a week. Not least because the National Academy is in residence at the National Arts Club and I am excited to go to work in such a beautiful building! Also, like a lot of us, I miss experiencing the stimulation of the city every day. I might even go so far as to say I need it – my mind is sharper and I feel more creative when I have access to the city’s energy. But I think we are all waiting to see what happens with the change in weather in the fall. Ultimately, we have to do whatever we have to in order to eradicate COVID, and if it means working from home for a while longer, then that’s what we’ll do.

What is something that you are especially excited for in your new role?

This is an easy question – I am excited to work with the Academicians. They are such a remarkable group of artists and architects, the heart and soul of the National Academy. It’s their vision and enthusiasm that ultimately moves the NAD forward. And as we do every year, this fall we will induct a new class of Academicians, who bring with them new energy and ideas. Of course, this year’s induction ceremony will be unlike any other, given that we have to rethink it as a digital event. But that opens up so many opportunities, because for the first time not only can National Academicians from across the country attend the ceremony, but we can also open it to the public and welcome a larger audience than we ever could have by holding a live event in New York. It offers so many possibilities for how we celebrate the work of the incoming Academicians and I would not be surprised if this has a lasting impact on the Induction ceremony. Silver linings everywhere.

–W.A. Demers