Jane Nylander, busy at work on the book, the image on her

computer screen is that on page 38 in the book featuring the

“Oldest Residents” in Manchester, N.H., Centennial, 1896.

Parades, a community staple to mark annual holidays and special events, have a storied history in America. Jane Nylander, who has enjoyed Old Home Day parades in New Hampshire for most of her life, has recently lined up several years of research and published The Best Ever!: Parades in New England, 1788-1940, which stepped off the press at Old Sturbridge Village in late 2021. We pulled up a curbside folding chair with her to find out more about what inspired the project, what she learned during her research and where the tradition is headed.

What prompted the book?

It was something that just developed from my own antiquarian sensibilities: my longstanding interest in the way ideas and memories are expressed tangibly started it. I have watched the Old Home Day parade in Freedom, N.H., since I was a little girl; eventually it struck me that things like this are really folk art. I was interested in how cultural history was portrayed, especially the floats. What really struck me were the stereotypes and what constituted “old.”

I’m not familiar with other books on the subject – is it a previously researched topic?

There are some books. What I found was that most books that discuss parades as a topic – rather than individual parades – rely on the same: The Grand Federal Procession in Philadelphia in 1788, and in the Twentieth Century, the Rose Parade, Mummers, Mardi Gras, and, always, the Fourth of July. The illustrations are very repetitive.

Since the small towns are usually missing, I started working in the local historical collections and found rich resources everywhere. Historic newspapers and stereograph collections were especially useful and revealed a lot about unfamiliar things like Floral Processions in the 1840s and the Antiques and Horribles, which began about the same time and continues even today. A lot of major Nineteenth Century commemorative events had souvenir books published that describe the parades; I’ve made a collection of those. Now I am left with an office piled with books that have to be sorted and passed on.

What is the origin of parades?

You have to go back to Classical antiquity. Depictions of those are very hard to find but you begin to see parades represented in paintings during the Renaissance.

How long did this book take to research and write?

I started the float research 16 years ago, after I had retired; it was a very interesting project that gave me an excuse to travel, to visit places I’d never been to or go back to others where I had found rich collections of ephemera. The really hard part was deciding when to stop. I worked on the writing for four years and had a publisher lined up, but when he sold his company in 2018, I felt stymied and stopped for about a year. After Bauhan Publishing and Old Sturbridge Village stepped up, I pulled together everything I’d done and then spent a very intense year selecting illustrations and revising text. I was pinned down at the start of the pandemic. Remote work made it difficult for me to get all the illustrations in high resolution and to meet deadlines. A lot of curators didn’t have access to their collections, but some people really went out of their way to get images to me: men in Vermont opened up historical societies in snow to retrieve things for photography, for example.

Why the date bracket of 1788-1940?

I began with the oldest float I could find: a huge ship from the 1788 New Haven Procession celebrating the Ratification of the Constitution. It was last used in the 1880s and is still in the New Haven Museum. It had its original sails until fairly recently, but they have since been replaced. It’s really remarkable for such a large thing to have survived.

As I worked, I realized that after World War II, parades changed, illustrations changed. Much of the newspaper photography was syndicated. Kodachrome was the standard for amateurs, but those photos are all turning yellow, so I decided to stop at that point. It was really a practical consideration. I had plenty of prewar material and I wanted to open up unfamiliar things for people, to dive deep into origins of the regional parade culture.

The press release for the book describes it as exploring the parade ‘traditions as enacted in the small cities and towns of New England’; was the parade tradition in large cities different? In what way?

They are essentially the same but much larger in the cities, of course, and much better known. The small towns didn’t have the huge parades, but their parades may have been even more influential, since they showcase individuals and ideas of local significance. At the same time, they make clear which ideas and images were widespread.

The book title is The Best Ever! What’s behind that?

The detailing of the parades is rarely complete, and a newspaper account is short. As I kept reading about parades, I found that the accounts usually conclude with a comment like ‘it was the best ever!’ or ‘the finest ever seen here!’

Are most of the parades seasonal?

They are more often in summer. Parade planners hope to ensure good weather. It is no surprise that there are very few George Washington birthday parades here because it is often snowing on February 22. It has to be a pretty special event to happen in poor weather. The first ratification parade in Boston took place two days after the Massachusetts legislature voted to ratify and it happened in snow! The usual calendar features St Patrick’s Day parades and the Evacuation Parade in Boston all on March 17. April 19 becomes important with Lexington and Concord. In June, you have Flag Day, Old Home Day in August throughout much of New England, and of course, the Fourth of July.

“Mayflower.” Haverhill, Mass., 1890. “From A Record of the

Commemoration, July Second and Third, 1890 of the Two Hundred

and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Settlement of Haverhill, Mass.”

Boston: Joseph George Cupples, 1891.

Have parades always been on holidays?

No. A holiday may be suddenly declared to celebrate a victory. Some parades welcome visitors, like Lafayette, who visited America in 1824-25 and was welcomed by a parade or procession in every town he visited so there wasn’t a single holiday. Community anniversaries stand by themselves. There are regionally special parades, then national ones; the Fourth of July parade is the most unifying.

What was the inspiration for Old Home Day?

It was the brainchild of Frank Rollins, the New Hampshire governor in the 1890s, who was worried about depopulation in rural New England. He realized that abandoned farmhouses would made great summer residences. It would be beneficial to the state as a whole if people were encouraged to come back, meet friends, have a reunion. It would also be an economic boost to the communities. The first one was in 1899 in New Hampshire, it quickly spread to other states, and continues to this day, usually with a parade.

What stories do New England parades tell?

There is often a historical section with a chronological component, which is highly selective. It usually starts with floats depicting the founding of the town, patriots, the founding heroes and the Declaration of Independence. The rest changes over time, showing progress, industrial innovation and cultural change.

How do parades change over time?

In a couple of ways. Horse- and oxen-drawn floats and elements give way to motorized vehicles. Sometimes a nostalgia factor reverts back to include horses and oxen. Torch-light parades are replaced by electric or gas streetlights. In the mid Nineteenth Century – mainly between 1850 and the Civil War – there was a change from tradesmen with tools to extensive displays of products. There was an overwhelming number of floats with various products. An example of that would be men who had a host of delivery wagons using many to display their wares. Parade organizers recognized that this was a cheap way to make a long parade that advertises the community with the business owners bearing the expense.

Another thing that has changed is that today there are far fewer people walking or marching. Some parades go for miles.

How intertwined are civics and parades? Businesses and the trades and parades?

Very much intertwined. Parades are a unifying feature for communities and values. They both express community members’ responsibilities to each other and celebrate the rights and duties of citizenship. They often feature politicians and political candidates making a big deal of seeking votes and energizing supporters. Sometimes the parades lead to a central place where a speech is given. In the Nineteenth Century, there was usually a reading of the Declaration of Independence as well as a long political speech about national and local issues.

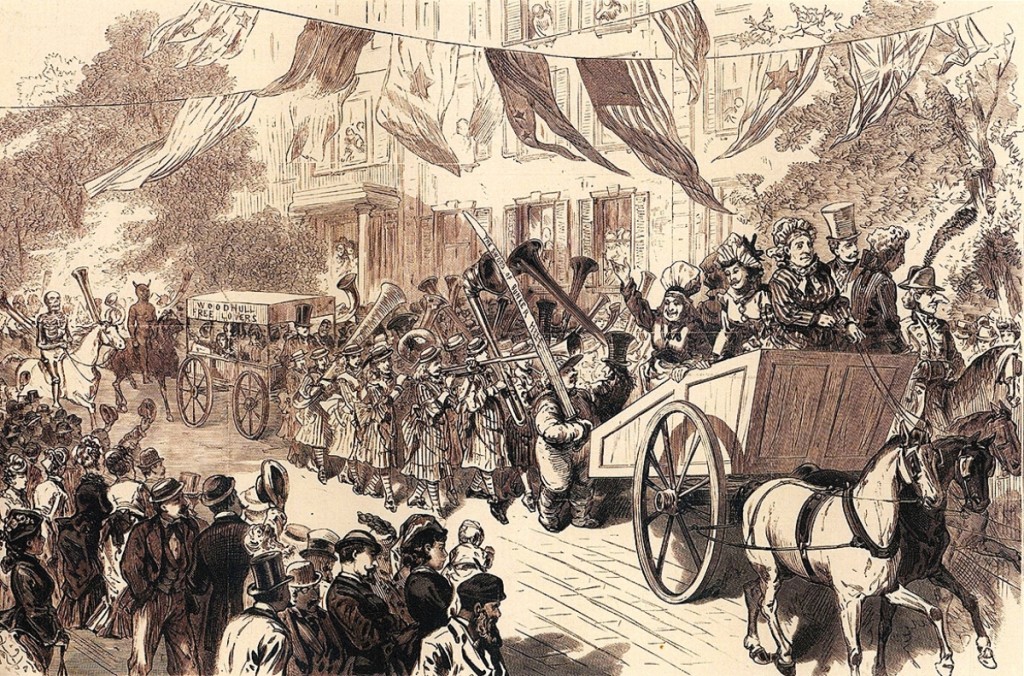

“Parade of the ‘Antiques and Horribles’ in Charlestown, Massachusetts on the morning of June 17, 1875.” Wood engraving after a sketch

by E.R. Morse and Harry Ogden. Supplement to Frank Leslie’s

Illustrated Newspaper, July 3, 1875. Private collection.

What were some of the revelations to you in the course of your research?

The extent of the ‘antiques’ and ‘horribles’ elements, the extent of the public criticism of current issues and even individuals. The involvement of women from the beginning.

What is the longest running parade in New England?

The Bristol, R.I., Fourth of July parade. The first one was in 1785 and it still goes on. There is a lot of community pride around it.

What were some legendary parades?

The 1788 Grand Federal Procession in Philadelphia and the 1825 Procession for the completion of the Erie Canal.

When did firefighters begin to take an outstanding role in parades?

I think it parallels the acquisition of uniforms and equipment. I looked for this beginning with the Erie Canal procession as I didn’t see it in the 1780s ratification parades. By 1820, you begin to have more fire engines, and then fire fighters become very enthusiastic participants. In addition to marching in parades, they developed firemen’s musters as events where they can display their skills, competing between the different companies. They offer prizes for the best uniform, the largest turnout, the unit from the greatest distance, pumping the highest stream of water, etc.

Do you think parades will be a tradition threatened in the post-Covid world?

No, I think the parade tradition is too deeply engrained. People love doing this stuff. There is always a challenge to improve on a previous year’s parade, or to try to illustrate an idea they’ve thought about for years. After so much time isolating from Covid, it will bring people together. It will be wonderful to be back.

-Madelia Hickman Ring

Editor’s Note: The Best Ever! Parades in New England, 1788-1940. By Jane Nylander Published byBauhan Publishing & Old Sturbridge Village, Peterborough, N.H., and Sturbridge, Mass. 2021, pp. 384, $45 hardcover, $30 soft cover. To order, https://www.osv.org/jane-nylander/ or https://bauhanpublishing.com/.