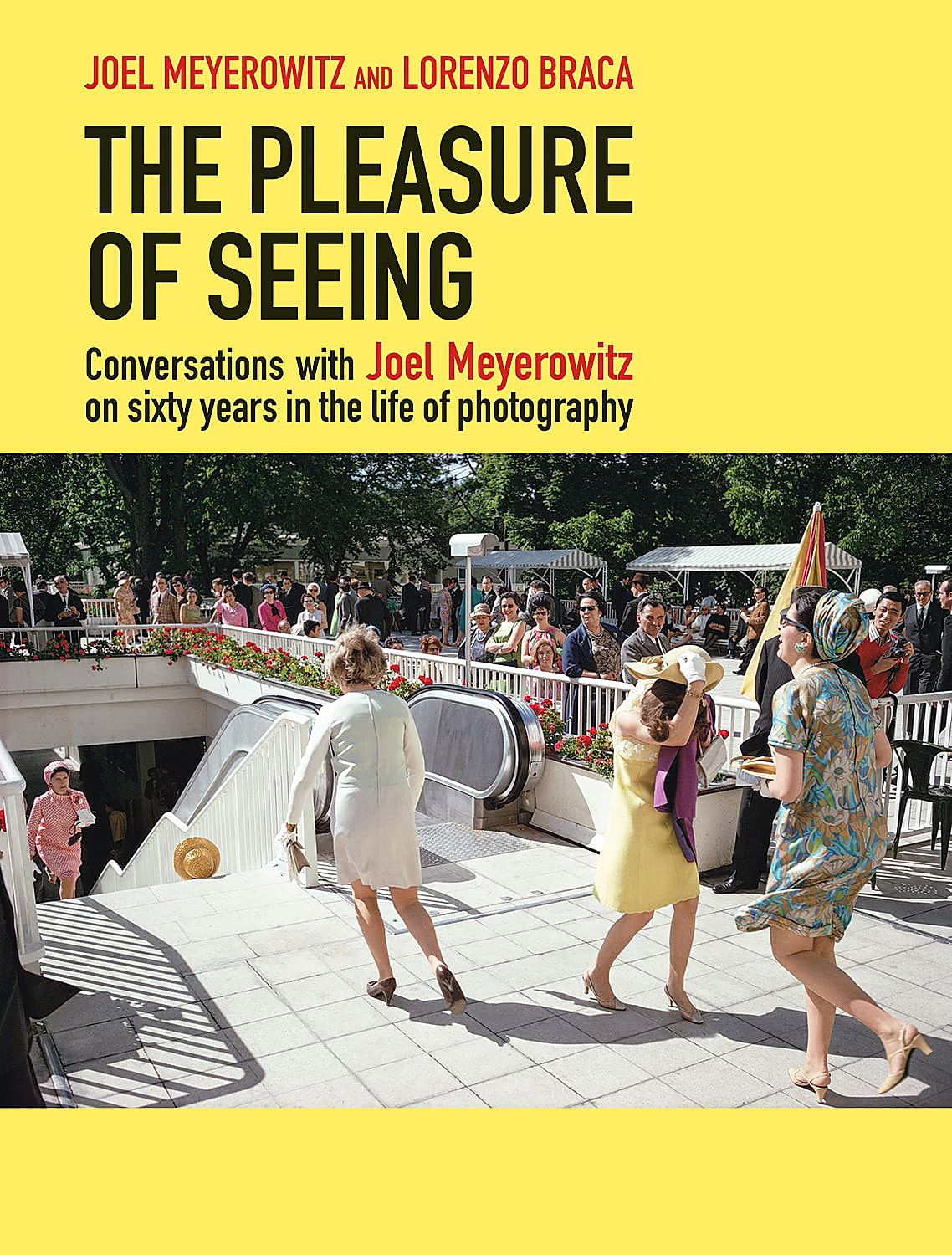

Joel Meyerowitz (b 1938) is an award-winning photographer whose work has appeared in more than 350 exhibitions in museums and galleries around the world. Celebrated as a pioneer of color photography beginning in 1962, he is a two-time Guggenheim Fellow, a recipient of both the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities awards, and a recipient of The Royal Photographic Society’s Centenary Medal. He was the only photographer allowed inside Ground Zero where he worked for nine months creating the history of the monumental recovery efforts. Meyerowitz has published 46 books, and he lives and works in New York and London. Antiques and The Arts Weekly was lucky enough to correspond with Meyerowitz while he was on tour for The Pleasure of Seeing, an oral biography of his career reviewed in conversation with historian and photographer Lorenzo Braca.

When and how did you and Lorenzo Braca decide to publish a book centered on your conversations?

During the pandemic we spoke a lot on the phone, and one conversation became two, then three and then two years later we had this long form that made itself into a “Talking Book.”

Unlike your previous publications, The Pleasure of Seeing is more of a long form interview than a traditional photography book. Which genre would you assign to it?

This is an intimate talk between friends about the nature of photography and the life I lived in it for the most intensive 60 years in the medium’s history.

At the beginning of your career, street photography was not considered documentary photography. Has your work from that period, and later, become so now?

No, it’s still more of a personal reflection on what the world had to show me and how I could learn who I am through the medium. I forged my identity through it. Only in the sense that the “then” has “now” become history and something of the time can be understood from looking at it. In that way…maybe…it has documentary energies.

Why do you think your photography inspires a sense of nostalgia for those who were born years, even decades after some of the photos were taken?

The time we are living in appears to be so insular and cut off from “real” intimacy in the public sphere and in social relations that I feel people today seeing these images of the past make them long for that kind of daily connection and reality.

One subject that comes up a few times in the conversations of your avoidance of clichés. How easy or difficult is that to accomplish?

When you speak from a deeply personal experience it nullifies clichés.

Another recurring topic is the surrealism that street and landscape photography sometimes inadvertently reveal; is there a photo or photos of yours that illustrates this?

Right from the beginning there are images that resonate with what we attribute the term surrealism to today. More than real. There are some examples in the book.

In one part of the text, you say, “Meaning is the Holy Grail of photography.” Do you find that your photographs have changed meaning over time, or even just after you develop them?

Meaning comes slowly. The fraction of a second in which the image is put on film leaves the seer with only the vaguest sensation of the potential for meaning to cohere. Only after, when a print is made and time is spent looking and taking it in, does its place in one’s lexicon of ideas and their meanings emerge, and that’s still a “maybe.” Meaning is slippery and not everyone gets it. But if the maker does, then it has a chance to stand on its own.

Many of your photographs were developed with the ability to be printed to life size, how do you think viewing them on a smaller scale affects their impact on the viewer?

The image in the original is actually 8 by 10 inches, so they are small, and printed at 8 by 10 inches is “jewel-like” and quite sufficient in themselves. But it’s their capacity to be enlarged say to 8 feet or more that carries that potential I spoke of.

The arrival of high-resolution cellphone cameras and social media apps like Instagram has changed how artists grow and develop within this medium. Where do you think this will take photography next?

Probably the instant ease and utility of image making will awaken the desires in millions of people to take this new “universal language” of the “image” in a more serious way. I expect there to be a huge jump in the number and range of artists who will emerge from this discovery. Of course, it starts with the generalized junk we see all over the web, but out of that will come new visions for the Twenty-First Century.

[Editor’s note: For more information about The Pleasure of Seeing and Meyerowitz’s available work, www.joelmeyerowitz.com.]

—Z.G. Burnett