If art’s most basic purpose is to communicate with a viewer, who better to parse the nuance of conversation than a collector with a career in technical communication. Joel Third spent much of his life building the infrastructure for communications, the groundwork that no one thinks about when they make a call or view a television program, so it makes sense that he would appreciate those who laid the groundwork long ago as they documented travel routes, our understanding of the natural world and the images that would become “us” or “ours.” Antiques and The Arts Weekly sat down with Third to talk about his collecting career and where it has taken him.

What is your affiliation with the Keeler Tavern Museum and History Center?

My late wife, Bettie Jane, joined the board of directors and became a docent after we arrived in Ridgefield in 1992. She persuaded me to become involved with the museum. I became president in 2012 for a four-year term. During that time we had a capital campaign to acquire and update the property next door. Cass Gilbert’s son built the brick home, now the museum’s Visitors Center, in the 1930s. We bought the property back four years ago, completing our four-acre campus. I’m still on the board and serve as the development director. I’m very pleased that the museum has great donors, volunteers and members, as well as a creative, dedicated staff, all who assure our viability as a nonprofit. The museum’s special focus is education, supporting the curriculum of around 2,000 students a year from the 4th grade to middle school, from not only Ridgefield, but also surrounding communities. Plus, I’ve given talks and exhibits at the museum. I owe my late wife a great deal for opening up the rewarding opportunities for volunteering in Ridgefield for me and actively participating in the growth of the print collection.

Tell me about the exhibits you’ve done there.

I started with an exhibit and related talk on John J. Audubon in the late 90s, to obtain experience with presentations. I was planning to retire, which I did in 2007, and I needed challenging pursuits to keep active. After that experience, I did exhibitions at Founder’s Hall senior center, Ridgefield Men’s Club, other organizations and more recently at the Ridgefield Library, where over the last five years I have done three extensive exhibits and related talks, the last on Audubon, but also earlier ones on Currier & Ives and antique maps.

What did you retire from?

In 2007 I retired from Harris Corporation headquartered in Melbourne, Fla. After graduation from Case Western Reserve in 1960 with an electrical engineering degree, I started out as a communications engineer for ITT Inc, International Telephone & Telegraph. I traveled all over the world. In 1990 I joined the international marketing and sales group at Harris Corporation. We worked on contracts with whoever wanted a communications system. When I started with Harris in 1990, we moved up to Montreal from New Jersey. In 1992, I interested the management in initiating a marketing “relationship” position, focusing on AT&T, Ericson and other large telecom providers. We chose Ridgefield, Conn., to settle down in, which is located about half-way between the AT&T complex in North Andover, Mass., and Bell Labs in New Jersey.

Did you do a lot of work with maps in your job?

Oh, I certainly did. Back in the day before the Hewlett Packard calculators, we used basic slide rules and maps and we had to lay out point-to-point systems across the landscape, and they had to work with no obstacles. So we did a lot of work on maps and even did field surveys in, as examples, Germany, Ecuador, Vietnam, Angola and other African locations, as well as in the United States and elsewhere. One of my most memorable systems was the educational TV system in Mississippi when PBS was first getting Sesame Street launched. Mississippi Educational TV placed TV transmitters for statewide coverage but lacked the interconnection with Jackson, the network center. We designed and implemented a microwave transmission system to connect all the transmitters. Because of the lack of detailed maps, considerable field survey work was necessary and I kept thinking, what if this doesn’t work?

When did you start collecting?

I started collecting maps in Germany in the 1960s, acquiring a map at a Frankfurt antiques market and then from other countries, such as England and Portugal. And other sources, including dealers such as The Old Print Shop in Manhattan, visiting English dealers, New York shows and auction houses. I learned about the hobby from all these groups.

So map collecting was your first area of interest?

Map collecting was my first interest, then the Nineteenth Century Audubon bird prints and Currier and Ives lithographs.

When you first started collecting maps, what were you drawn to?

The age, historic significance and the artistic appeal. I was pretty eclectic; initially I didn’t focus on any one area. In later years I focused on the United States, New England and the immediate area around here. This area I started off from an artistic perspective and then it transitioned into more of an academic perspective.

Right, you don’t understand the nuance at first.

Yes, start learning about the cartographers, the map’s age, historical significance and so on. I never had the means to buy the top-end maps, but there’s a lot in the middle-range maps that I could acquire.

Which of yours is your favorite map?

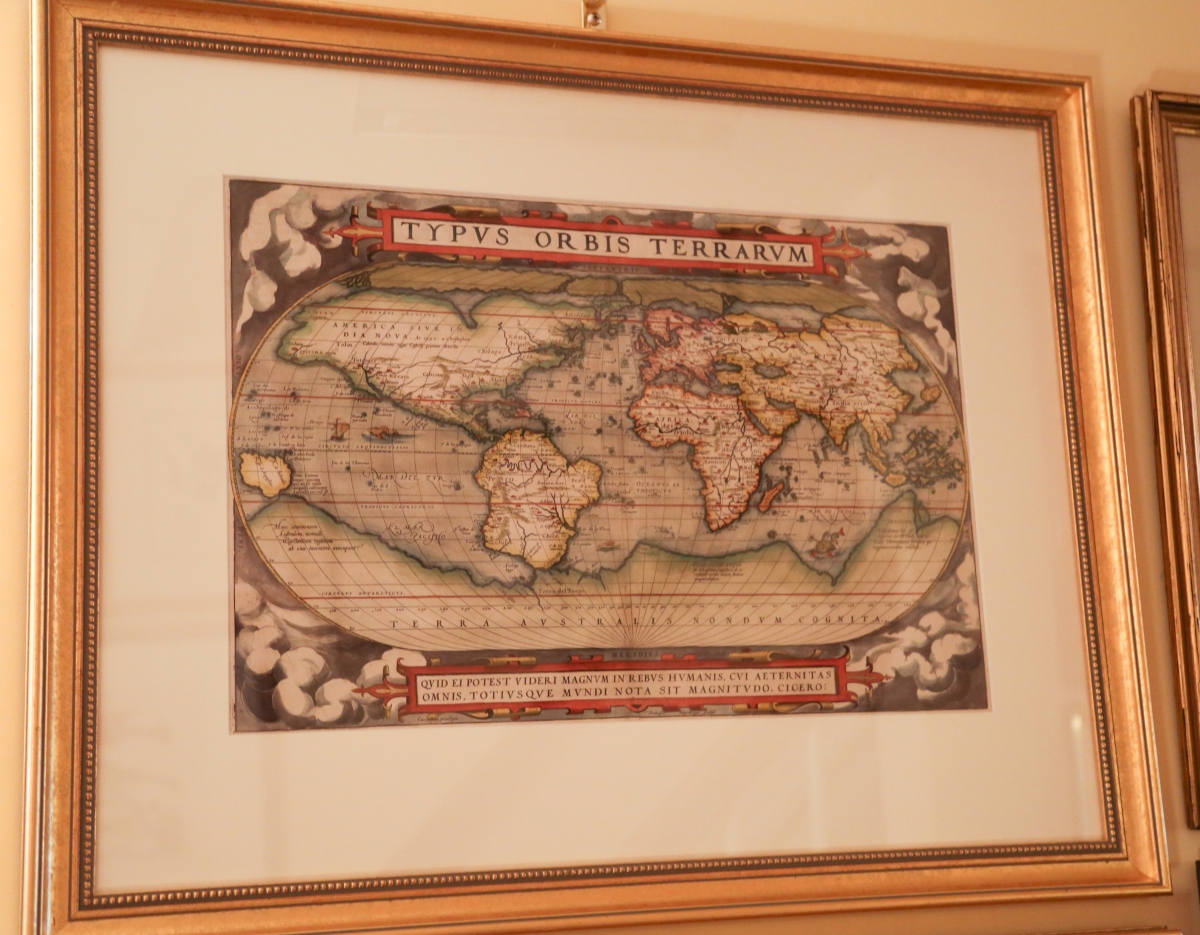

These circa 1550 maps here made by Sebastian Münster of Basel. They’re special because of their age and the early approach to the printing process: woodcuts, which was compatible with Gutenburg’s printing system. My Münster maps are from different editions of the same publication, but published at about the same time. These are all the continents and actually the first time all the known continents appeared in the same publication, Münster’s Geographia & Cosmographia. This publication was remarkable since the explorers were just obtaining geographical data that greatly expanded western knowledge from the Greco-Roman concepts. I am also fond of the Flemish cartographer maps, Abraham Ortelius of the Sixteenth Century.

Any others?

During the library exhibition preparation, I bought a very early world map by Laurent Fries initially published in 1522, my map’s edition is circa 1540. What makes it quite special is that it is the second time that “America” appeared on a map, influencing the public and contributing to our continent’s final name. The first time was around 1507 by German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller who later removed the name realizing that Columbus had the “Primacy of Discovery.” There are of course many other interesting Seventeenth Century publishers such as the Blaeu family of Amsterdam and the John Speed/Francis Lamb American colonial maps from London.

Any other areas of maps that you explored?

I’ve collected New England maps as well. This map, titled…Most Inhabited Part of New England…,published 1776, just before the American Revolution. A detailed German map that was published by Tobias Lotter of Augsburg, based on English cartographic information. Vermont and New Hampshire are shown together as a crown colony – this land all belonged to the king as a source of white pine trees used for his Royal Navy. Germans had an interest in America since they had people on both sides of the conflict.

I also have this 1559 Sabastian Münster woodcut print titled Monstra marina & terrestria, quae passim partibus aquilonis, inveniuntur, reflecting the public concepts of the sea monsters. Münster depicted a whole collection of sea monsters. It’s a fun print, and they’re all labeled in a map’s companion document.

Is that a lobster impaling someone?

Yes, it’s a giant lobster with a man in its claw. Sea monsters were promoted by the Islamic countries and others as an obstacle to the European exploration of “their” oceans, disrupting their lucrative trade and the very profitable silk route to China.

Clever.

There were also other reasons for promoting the monsters as people started to doubt their existence. It reached a point where if you were commissioning a map, you might pay extra for some monsters to enhance your map. Attractive, frightening monsters would sell maps.

Tell me about some of your other maps.

I have a colonial New England postal map, New England, New York, New Jersey and Pensilvania, from circa 1720 by an English cartographer Herman Moll. It shows and explains the route that a letter travels from Philadelphia to north of Boston. This map depicts the postal network and the travel times experienced. It was amazing, it only took about a week to get there.

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is considered to be one of the first modern atlases, published in 1570 by Gilles Coppens de Diest at Antwerp with 53 maps created by Abraham Ortelius.

Still does!

Yes, it does! The 1720 map is crude, it’s not a beautiful map, but it’s very historically informative.

Any that relate to your travels?

Yes, I stayed on Crete for a few months, working on a system contract for the US Air Force. In the beginning of the Cold War, we had bases and weapons all around the Mediterranean area and very little communications. Before modern cables and satellites, they were using ham radio channels, so they contracted ITT to implement a system for command and control. The size of the island is probably not as big as indicated on Tabu Nova Can (Crete), this 1525 map published by Laurent Fries, but it’s still lovely. I can see areas I used to drive around in my Volkswagen.

What about this one?

This is an important colorful Dutch map of New England, Novi Belgii… (New Netherlands) by Justus Danckerts, published in Amsterdam. This 1684 edition is the first to show Philadelphia and farm animals as an inducement for immigration to the new world. An idealized view of New Amsterdam is depicted and not New York, even though the British initially captured the city in 1665. You can see where the Dutch probably showed areas as theirs for political reasons back home. The Dutch were here for fur trading and other commerce, while the British were here to stay.

And you also collect works from John J. Audubon.

Yes, they all have their own unique look. They’re not as romantic as Currier and Ives or historically relevant as maps, but they’re timeless, beautiful and accurately capture nature of the Nineteenth Century. Audubon is a recognized important American artist as reflected in the prices for his original prints.

How did you decide what birds you liked?

I like many of Audubon’s prints, such as the osprey, white pelican and bald eagle, but collect what’s available at affordable prices.

Any one format?

No, formats are dictated by availability and cost in different genres. I have some original Robert Havells, Audubon’s English engraver/publisher, from Birds of America of circa 1830. I also have some Audubon animal prints from The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, folio or large edition of 1845/48 like the “House Mouse” print. I also collect the smaller octavo edition, which are 1/8th of the size of the original prints. Audubon started Quadrupeds, but his sons finished it, since Audubon had dementia. He died in 1851.

I also have some chromolithography prints of Audubon birds, considered the second edition, his sons were producing these lithographs in 1860. However, the American Civil War cut off their Southern customers, bankrupting the effort. And I have a modern, very accurate, full-sized digital reproduction of Audubon’s original painting from Joel Oppenheimer, a Chicago dealer who I’ve known for some time.

Do you expand to any of the other naturalists?

I also have some original prints by Alexander Wilson, one of the first American ornithologists, and in my library exhibition I compared Audubon art with influence of Wilson and Mark Catesby, an English naturalist/artist of the Eighteenth Century colonial period. I like Wilson’s work, even though it wasn’t to Audubon’s standards. He had a knack for placement, placing multiple birds on the same plate because he couldn’t afford to do them individually. He did a good job of publishing the first recognized ornithology in the new American nation in circa 1813.

Onto the Currier and Ives (C&I) prints. What are your favorite scenes?

I love the Mississippi River prints. Fannie Palmer, an English immigrant, who was the C&I artist who drew these lithographs, she never visited Mississippi; she based her scenes on stories and descriptions. She also drew railroad scenes, which I like. The process invented in the late Eighteenth Century is amazing. It starts with a limestone block weighing 400 or 500 pounds with a finely ground surface. Limestone is fragile so the large blocks are five inches thick, if it was thinner it wouldn’t survive. They drew the original image on the stone with a greasy crayon as a mirror image. After watering the stone surface, ink was applied and the image was printed, in black and white, and then hand colored. The large-format prints are quite a bit nicer than the smaller ones, even though some of the smaller ones were quite good. They sold the large black and white originals to artists in Greenwich Village for coloring who would sell them back to Currier and Ives for final distribution and sale domestically and internationally. The smaller prints were colored in house using an assembly line arrangement.

Novi Belgii… (New Netherlands) by Justus Danckerts, published in Amsterdam.

Third says, “This 1684 edition is the first to show Philadelphia and farm animals as

an inducement for immigration to the new world.”

Why did you fall in love with Currier and Ives?

The images appeal to me. They have a historical reference quality as truly Nineteenth Century “mass-media,” plus they have a very romantic appeal to them. I think you have to be sort of a romantic to get into this genre. When you start doing your research, you find this a reflection of the growth of the new country in the Nineteenth Century, displaying the immigration, the movement to the cities, women’s rights, the temperance movement, etc. C&I published about 7,000 titles and millions of prints over their 73 years in business starting in 1834. The prints were popular as visuals for immigrants with language difficulties. Newspapers were not printing images, so these images were the public’s “mass-media.” C&I printed an idealized version of America with little poverty expressed. However, they did show the “evils of drink” while publishing beer ads at the same time.

They made it look very exciting to travel up those rivers.

Yes, they had all these beautiful descriptions to accompany them on these tours. And then the boat races – it was a big deal with lots of betting. The steam vessel owners would strip the boats to lighten the weight and they would hit the boilers so hard that sometimes they would explode.

Did they travel the whole river when they raced?

Usually from New Orleans to St Louis, it would take three or four days. I have a print that tells you how long it took down to the minute. It’s a very good reflection of our history with great public interest.

Did Currier and Ives create the American image?

Yes, they certainly contributed to the view of an idealized nation and its technical advancements. The immigrants in the new country wanted their own history, so Currier actually answered that need by promoting our founding fathers and American history. They did Christopher Columbus landing, then totally ignored the colonial period, and picked it up again in the revolutionary period, which probably meant a lot of the immigrants who were not terribly fond of Britain early in our history.

Louis Maurer did a series of the fire-fighting volunteers and later municipal systems in New York, that was an important step. He did them in the 1850-60 period. Currier was a volunteer at one of the volunteer fire clubs. A lot of C&I prints are New England-centric, there’s not much about Jamestown, however, Plymouth is nicely documented.

Any other Currier artists you like?

I’ve got some large Curriers, some done by Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait, a British immigrant. He also did these Western scenes; they were very dramatic. And there’s just something about these Curriers that really attracts me. Once you see a Currier and begin to study them, you’ll always recognize them.

Do you collect Curriers from the “Best 50” list?

Yes, most of these are on that list, but I didn’t try to check them off, no. But if it’s on that list, you’re going to pay a premium for it. The “Best 50” lists the most popular prints by collectors and dealers.

How many Curriers do you think you own?

Around 75 I guess. The small ones add up. I would like to hang them, but I ran out of wall space.

Anything you’d still like to acquire?

There’s a Currier I’d like to get, dealing with the railways, three engines leaving the station, very dramatic. The last time I ran into it the price went through the ceiling.

Can you describe your collecting journey?

Collecting is really four phases. First, you get an interest. Then in the second phase, you start to collect and display it. The third phase for me is community, sharing your knowledge and collection, especially with young people. And the fourth phase is the estate planning, what you’re going to do with them at the end.

And it looks like you’re full.

I’m out of space. The Keeler Tavern Museum is finishing the basement on the lower level of the new Visitors Center for our archival storage, and once that gets done, some of the collection will go there.

-Greg Smith