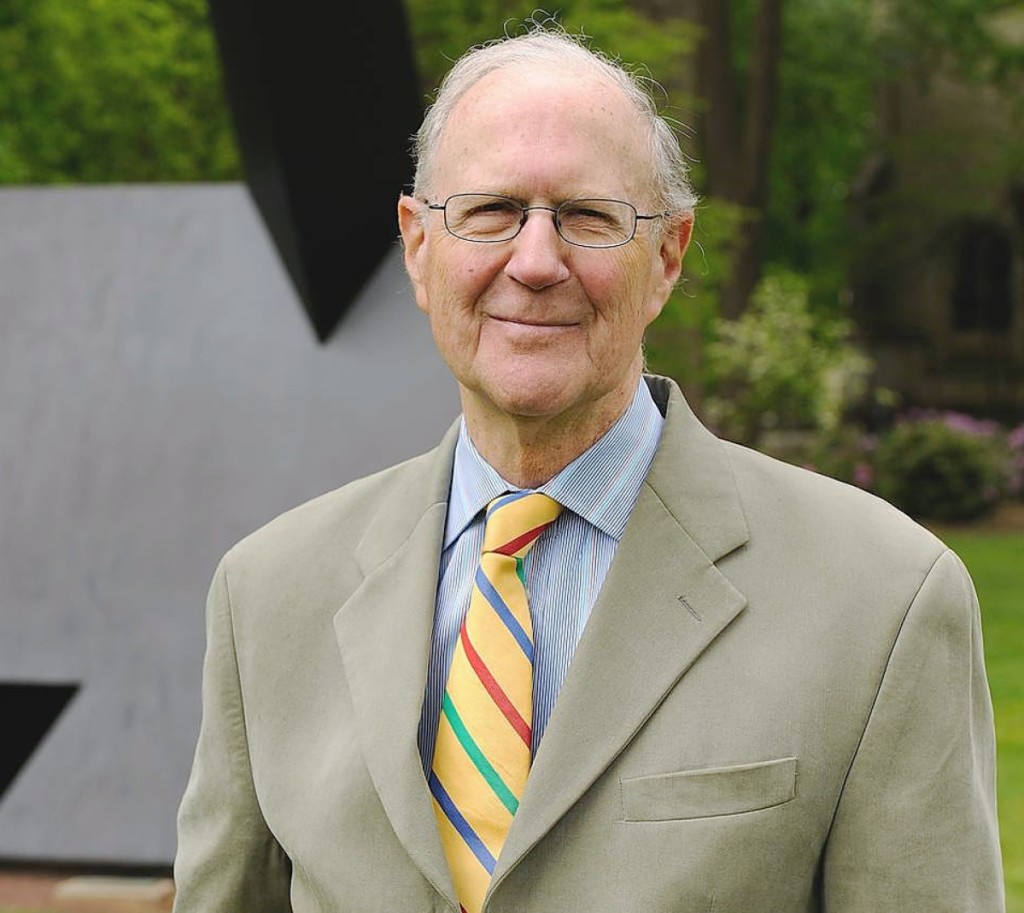

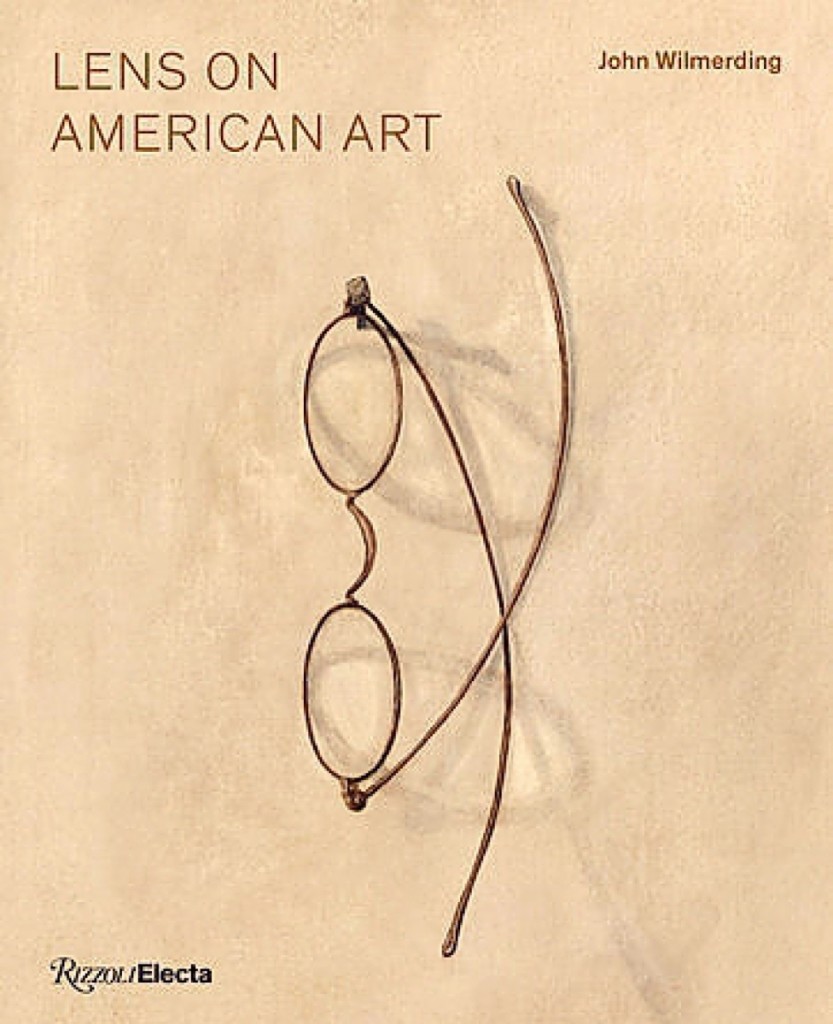

In the 24th book from art historian John Wilmerding, titled Lens on American Art: The Depiction and Role of Eyeglasses, the author turns his attention to, as he phrases it, “eyesight and insight.” What follows is a physical, psychological and sociological study of eyeglasses in American art from the Eighteenth through the Twentieth Centuries. The author explores the accessory through contrasts such as necessity and vanity or outward facade and inner thought, but also on a case-by-case basis as they specifically relate to the finest works in the American canon. We sat down with Wilmerding to receive some of that insight from this playful title.

Tell me about the book’s genesis.

When I was a curator at the National Gallery, one of the first major paintings I was able to acquire as a new curator of American Art was the portrait “Rubens Peale with a Geranium” by Rembrandt Peale painted 1801. It was a momentous event, it was the first painting the National Gallery had purchased at public auction. So J. Carter Brown went up to New York and did the bidding with Larry Fleischman and we acquired it. It was quite a sensation, close to $4 million, and this was back in 1985 – that was a huge price, it set a record for American art at the time. That brought us a lot of attention. As a curator, I had to do some writing on it, particularly for the collection catalogs and I later published a book American Masterpieces in the National Gallery, and the Peale was front and center. I can’t remember if I was the first to notice or not, but one of the things I noted was that Rubens is holding a pair of glasses in his hand and he’s wearing another pair of glasses on his nose. If you look closely, I noted the fact that they were not identical glasses. That didn’t quite make sense, and the closer you looked – and you often couldn’t tell this from reproductions, you had to look at the painting carefully – the shape of the glasses is not identical. The bridge of the glasses in his hand is slightly wider than the bridge of the glasses on his nose. This is the first case where I was looking at eyeglasses in a painting. I always love that painting and every time I go back I see something more.

Why the difference?

Once you realize the glasses are not the same, you need to ask “Why?” “What do they represent?” The solution is that one pair was for looking close, the other pair, worn on his nose, is for distance, which he wears to look at the viewer. If anything, that painting was in my mind one way or the other. I had also written essays on Charles Willson Peale’s two other paintings on Raphaelle Peale and Titian Peale in the famous staircase group at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Charles Willson Peale wore glasses most of his life. The more I explored the sons, Rubens and Rembrandt or Titian and Raphaelle, they all wore glasses, which led me to the correspondence with Peale and Benjamin Franklin. Peale was talking informally to Franklin asking him to get his boys glasses, as they were always falling over things. So the Peale paintings were the grounding.

Lens On American Art by John Wilmerding; Rizzoli Electa, www.rizzolibookstore.com; Release March 24, 2020; hardcover; 184 pages; $50.

Why is Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of Benjamin Franklin notable?

I always asked my students to read Franklin’s autobiography. It’s not only fun to read, it’s a very original book in that he shapes it as he wants. The story of the autobiography only goes up to 1745, the first half of his life. It’s something very playful and formally inventive. Even though it’s in the first person and all about Franklin’s ego, that book is really our first book of American literature as opposed to Colonial literature. One of the anecdotes that suddenly became relevant, upfront in the first chapter, is one where – and you have to wonder how much of it is total Franklin or partial self-invention – but it’s the description of a diplomatic dinner table in Paris when Franklin was an ambassador to France. He was complaining that he couldn’t see the French diplomat very well across the large dining table. He could see his food in front of him very well, but wondered why he couldn’t have eyeglasses that could accommodate both near and distant sight. He then comes back and writes to his glassmaker to cut apart his glasses for distance and reading and put them together in one frame, which leads to the invention of bifocal lenses. Later Franklin claimed bifocals made him a much better conversationalist. That little incident, in 1784, was the perfect starting point. Peale’s painting of Franklin is a year later in 1785.

Could you find any American portraits with subjects wearing glasses before that?

Before the Peales, I couldn’t find any Americans that painted eyeglasses. Not even Copley.

Were there any moments in time when eyeglasses started showing up more often?

At the Shelburne Museum, you see glasses with a lot of anonymous artists, true folk artists of the Nineteenth Century. It leads one to believe that there were also economic concerns. Eyeglasses were becoming available, not just to the elite or the wealthy, but to all classes. So you have an increasingly educated citizenry who want for information, not just reading books but particularly newspapers. There are all kinds of sociological aspects, including changes in teaching and schooling, the teaching of literature – but it’s all part of the accessibility. The fact that shopmakers and salesmen could put out these huge signs over the door, again, that’s looking to a much wider public. In that sense, it’s the democratization of the subject itself. They’re available; there’s a need for them. The fact that not only well-known or established artists, but folk artists were painting them, means that they were much more widespread.

Were you able to make any observations about gender?

There are not many portraits of women wearing eyeglasses until well on in the Nineteenth Century, and my speculation is that it relates to fashion – that women must have thought they would look ridiculous in glasses or that glasses were associated with men’s work, for example, reading or writing. As I got into it, there were all kinds of social issues around the subjects.

You devote two chapters to Thomas Eakins, why the focus on him?

Now in this context, I’ve sorted through several hundred portraits that he painted. To my best recollection, there are around 30 paintings of his showing sitters with eyeglasses. The more you look at Eakins’ works, you realize that he’s interested not just in the physical presence of his sitters and his ability to paint anatomy, but he’s interested in the psychological presence, the inner character and the inner mind. By the time I got to the Eakins section, some of the other painters are about optics, that is to say the sitter needs glasses. But with Eakins, you are also aware that the sitters are often staring off into space, looking over their shoulder or to the side, they don’t seem to be focusing on any single thing that needs clarification. As I started looking at those pictures, I realized there was a whole category of painting where the eyeglasses not only help show us the direction the sitter is looking, but help confer a focus on something else, an inner vision. They’re not just staring vacantly, their thought is not in the physical world, it’s nothing recognizable. It has nothing to do with the prescription of the lenses, it is about inner vision.

Give me an example.

Eakins wrote about optics as it was directly related to his interest in perspective, in rendering space. It was the scientific aspect that he wanted to understand, as it related in both personal and professional ways to his art. One of the things the book afforded me was a chance to look at major works again that were utterly familiar to us, for example, “The Thinker” in the Met, where the full-length figure is standing, looking down at the floor through his eyeglasses. The way Eakins painted the eyeglasses on “The Thinker” is a tour de force. Technically, it is in foreshortened angle perspective, that is to say the head is bowed down looking at his feet through the glasses, so you’re not looking at the glasses straight on, you’re seeing them at an angle going back over the nose. This is just another example of Eakins’ extraordinary technical ability to paint realistically, a dazzling sort of illusionism. But if you look at it, the painting is deceptively simple: there’s no background, he’s standing there in a black suit, and it’s amazing one can perceive the sense of body mass, of bones, behind the ruffled pants and jacket, and that he’s given a sense of weight and gravity to the figure. Faces, hands and eyes were the most important thing to Eakins in his later work, and to track that I felt was an important subject in itself. The seeing, and the question of innerthinking: it’s not only a portrait of a figure, it’s a portrait of somebody engaged in thought. There’s something very mournful and melancholy about this picture that becomes its subject. You’re dealing with Eakins the psychologist. He’s presented a physical character with dexterity, but a physical presence and psychological interior. That’s an elusive thing to try and capture. The eyeglasses are crucial to explaining that. He’s looking through those lenses to contemplate. He’s standing on the threshold of the new century, he’s an unhappy character. The eyeglasses direct his glance from his head downward to the floor. You can take almost any of his major figures and, just by doing a little bit of close looking, you start to engage with a great artist using the most common of details to give the largest sense of meaning.

Did eyeglasses as symbols change over time?

Yes. Particularly in the Eighteenth Century, eyeglasses were expensive. They were a symbol of patronage and a certain degree of wealth. Once they did become fashionable for women and men, it was clear they could reveal personality. That leads to the modern convention where you have eyeglasses that are not corrective at all. Some people buy them to look a certain way. Then there was the statement where Rick Perry said he got a pair of eyeglasses so he would look intelligent. The most notable category, which occurs in various places in the book, is eyeglasses with the aged, the elderly. We associate eyeglasses with age – the fragility or vulnerability of old age itself. Probably the most obvious signifier is various kinds of intelligence with literate people, with writers and thinkers. And then you circle back to Charles Willson Peale, that wonderful self-portrait in 1804, one the first where he has his eyeglasses on his forehead. It’s also relevant to art, to look closely.

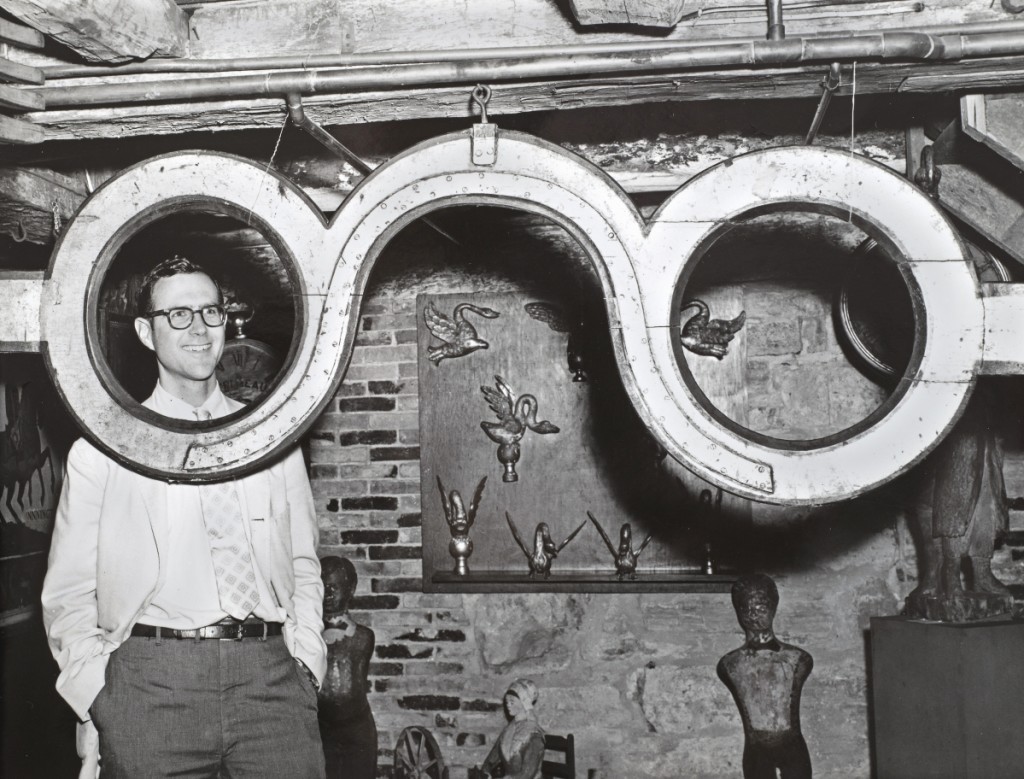

“John Wilmerding with Spectacle trade sign, July 10, 1968” by Einars J. Mengis.

Collection of Shelburne Museum Archives.

You go into Grant Wood a bit, tell me about that.

Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” is there a more familiar image in American art? But then you discover the detail that the glasses the farmer is wearing were those that belonged to Grant Wood’s father. There’s another photograph of the subjects: his sister who posed for the woman and the local dentist who posed for the man. In the photograph, the dentist is in fact not wearing those glasses that Grant Wood painted. They were more octagonal. So he substituted in those glasses that belonged to his father, one of the few accessories or items that he would have inherited. It led me to no real conclusions but at least some speculation as to the relation between these two figures in the painting. Everything from farmer and wife, to father and daughter, we know the wife was his sister, so there’s an autobiographical element. In portraiture, on some level as he wore these glasses, it becomes a portrait of Wood’s father and of Wood himself. The eyeglasses did lead to some kind of new observations.

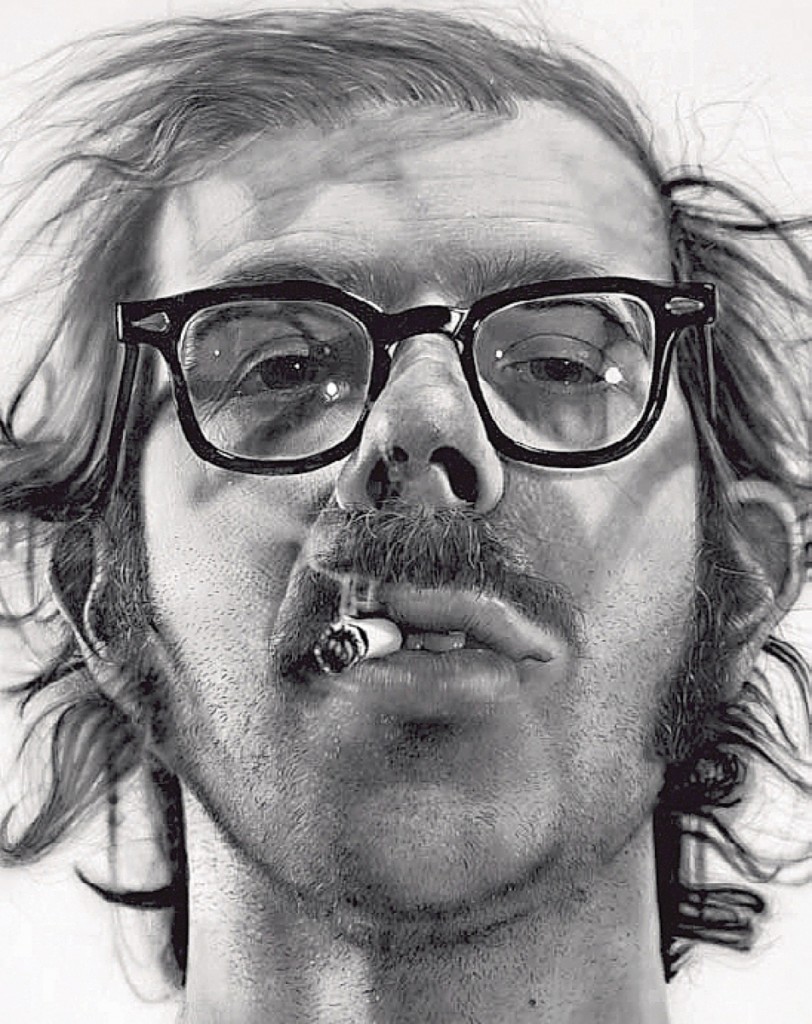

And then comes the postwar period and there seems to be a drastic shift in the Twentieth Century?

It becomes a spin-off of self-perception. Artists are clearly using eyeglasses as a form of branding. You dig into Keith Haring’s eyeglasses, I don’t know that he wanted to look like a raccoon, but that was his look. I knew Duane Michals, who did a wonderful photographic portrait of Warhol with his hands covering his face. It just made you realize that Warhol was about not just revealing but concealing. I asked him, “What about wearing sunglasses indoors?” He said that was just Warhol wanting to look groovy going to Studio 54. He did need eyeglasses, but as you look at Warhol’s self-portraits, a lot of it is self-presentation. To look fashionable, to look with it, to look youthful. That is clearly a signature aspect of contemporary artists. It’s like Oscar Wilde and his costumes or Whistler and his dandyism. Eyeglasses are a form of costume. As you know, when you go to the store to buy them, there exists every manner of shape and design. That goes into the Thiebaud paintings of eyeglasses, the counters of eyeglass frames have nothing to do with any known glasses, he is just showing the kind of variety that every designer comes up with. Talk to a lot of people going to buy eyeglasses, they see it clearly as a fashion statement. It’s a form of self-image making, self-image presentation.

-Greg Smith

Ed note: Lens on American Art: The Depiction and Role of Eyeglasses by John Wilmerding is available at the Rizzoli bookstore at https://www.rizzolibookstore.com/lens-american-art-depiction-and-role-eyeglasses.