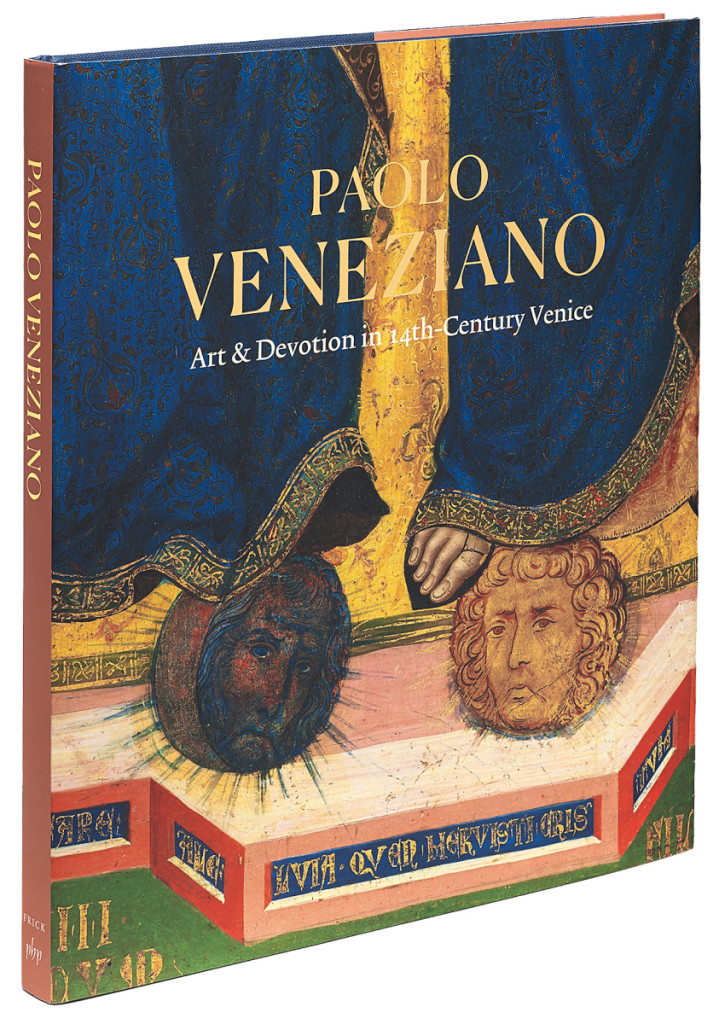

John Witty is the 2018-20 Anne L. Poulet curatorial fellow at the Frick Collection in New York City. He and Laura Llwellyn recently authored Paolo Veneziano: Art & Devotion in Fourteenth Century Venice, an in-depth look at the foremost Venetian painter of the Fourteenth Century, regarded as the founder of the Venetian school of painting. The volume, published by the Frick Collection in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, reunites, for the first time, the dispersed components of two of the rare surviving altarpieces and presents them alongside contemporaneous objects in various media. Antiques and The Arts Weekly sat down with Witty to discuss his scholarship.

What spurred you to do this research and book?

I had always been interested in Venice for its long history as a point of contact between many cultures. In the study of Italian art history, the Fourteenth Century has received less attention in recent decades. I was an intern at the National Gallery of Art in Washington before I attended graduate school. Their collections include an especially important work of early Venetian painting, “The Coronation of the Virgin,” by a painter who was most likely an older contemporary of Paolo Veneziano. This work was formerly attributed to Paolo Veneziano. I found the details of this painting and others from early Fourteenth Century Venice to be so vibrant and striking that I wanted to understand more about the period in which they were produced.

Who was Veneziano, where was he from and when was he active?

For late Thirteenth and early Fourteenth Century artists, it is often the case that we don’t know very much about the details of an artist’s life. There is no surviving record of Paolo Veneziano’s birth. Art historians estimate that he must have been born around 1290 in Venice. His earliest signed work has a date of 1333. His last known work, “The Coronation of the Virgin” in The Frick Collection, has a signature inscription dated to 1358. In 1335, a notary from Treviso mentioned Paolo Veneziano in a memorandum as the brother of a painter named Marco. He noted that both painters created works for the Franciscans in Venice and nearby cities. They are described as living near the church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, the principal Franciscan church in Venice. A property sale record from 1339 cites Paolo Veneziano as the son of the painter Martino. By this time, Paolo had moved to the neighborhood in Venice that held the greatest concentration of painters’ workshops. We can therefore conclude that Paolo was born into a multigenerational workshop of Venetian painters and that by 1339 he oversaw his own workshop.

How did his workshop come to get commissions from Venice?

Paolo Veneziano would have received commissions based on the reputation of his family and patrons’ satisfaction with his own work. By 1339, he seems to have attained a notable degree of success. When the doge, or elected ruler of Venice, died in 1339, the executors of his will chose Paolo Veneziano to create a panel painting for the doge’s tomb. In 1345, Paolo Veneziano painted images of saints and scenes from the life of Saint Mark for the cover that concealed the high altarpiece of San Marco on weekdays. San Marco was Venice’s state church and most important religious site. The weekday cover, called the “Pala Feriale,” has a signature inscription that emphasizes Paolo’s ongoing family legacy by naming his sons Luca and Giovanni as collaborators on the work.

Paolo Veneziano: Art & Devotion in Fourteenth Century Venice is available in hardcover, 10½ by 9½ inches, 168 pages, 112 color illustrations; ISBN: 9781911300953 for $60.

Why were altarpieces the vehicles for such art?

In late medieval Europe, the church had a strong influence over everyday life. Mendicant religious orders, such as the Franciscans and Dominicans, became increasingly prominent in the late Thirteenth and early Fourteenth Century. Through their literature and public sermons, they encouraged pious behavior by exhorting their followers to reflect on episodes from the life of Christ and the saints. Painted images helped adherents focus their attention on these subjects. Large-scale altarpieces were an important focal point in the performance of the mass. Images on an altarpiece could illustrate the life of a saint to whom an altar was dedicated or encourage viewers to contemplate the figures at the center of the Christian narrative -Jesus and the Virgin Mary.

Tell us about the two rare altarpieces and how they were able to survive.

The full scope of the exhibition that was originally planned for the Frick and the Getty featured two different kinds of altarpieces. The Frick Collection’s “Coronation of the Virgin” was the central panel of a large altarpiece that was originally displayed in the Dominican church of Santa Maria del Mercato in the central Italian town of San Severino Marche. When the church was updated in later centuries, the altarpiece was moved to a small chapel on the outskirts of the town that was also owned by the Dominicans. The central panel was separated from the rest of the altarpiece in the Nineteenth Century. It was a common practice for dealers in this period to cut up larger works of art so that they could have more objects to sell.

Following the newly formed Italian state’s suppression of religious orders in 1861, a local priest arranged for the altarpiece’s side panels to be hidden in a peasant’s home, where they were used as a bedroom screen. A senator from the region later appropriated the works for his private art collection. In 1895, he was compelled by legal action to surrender the panels to San Severino’s civic painting gallery. The Frick Collection’s “Coronation of the Virgin” surfaced on the art market in Munich in the 1860s. In 1873, it was purchased for the Hohenzollern collection in Sigmaringen, Germany. The trustees of the Frick Collection purchased the panel from M. Knoedler and Company in New York. The painting had been sold to a Munich-based dealer when contents from the Hohenzollern collection were sold in 1927.

The altarpiece reconstruction currently on view at the Getty is a smaller-scale triptych intended for private devotion. In fact, the exhibition features two different versions of the same type of object. One version has survived intact; today, it is a part of the collections of the Galleria Nazionale, Parma. Nothing is known about the whereabouts of the triptych before 1851, when it was documented in the Bourbon ducal collections at Parma. Since 1927, the Worcester Art Museum has owned a series of seven small panels of saints by Paolo Veneziano. Comparison with the Parma triptych shows that these panels can be put back together to form the wings of the triptych. The wings can be completed by two small panels with images of the Annunciation that the Getty purchased in 1987.

In the early Twentieth Century, they were a part of the collection of Charles Loeser, an art collector and heir to an American department store fortune who was living in Florence, Italy. A small panel bequeathed to the National Gallery in Washington from the Kress collection nearly completes the dispersed triptych. A panel from the Musée du Petit Palais in Avignon was long thought by scholars to complete the triptych. Undertaking technical analyses for this exhibition, a team of art conservators from the Getty, Worcester and the National Gallery determined that the measurements of the Avignon panel are too large for it to have been a part of the triptych reconstruction. This suggests that there may have been a third version of the triptych.

Paolo Veneziano (circa 1259-1362), “Archangel Michael,” about 1340-45, tempera and gold leaf on panel. Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Mass., museum purchase, 1927.

In what way was Veneziano considered innovative?

The standard art historical view of Paolo Veneziano is that he is a painter who simultaneously incorporated the styles of western European art and the Byzantine painting tradition. This is certainly the case, but it was our hope that the exhibition would present a more thorough view of the artist. Formal, static iconographies are the hallmark of the Byzantine painting tradition. Think of a frontally oriented saint standing against a gold ground, with small strips of gold applied to the saint’s clothing to create a schematic rendering of the drapery folds. Applying feather-light strips of gold to the painted surface is a technique called chrysography. Most often, Paolo Veneziano used chrysography to represent ornamental patterns in the textiles that the holy figures wear in his paintings. The patterns seen in his paintings are very close to those that were produced for expensive woven silk textiles in Paolo Veneziano’s lifetime. Textiles produced in Asia and the Middle East were traded into the European economy by Venetian merchants. Italian weavers created new designs in response to the imported goods. The design history of luxury goods traded in the global medieval economy can be read in the details of a painting like the “Coronation of the Virgin” in the Frick Collection.

What other disciplines was Veneziano exposed to that informed his art?

Fourteenth Century painters could be involved in many different creative endeavors. For example, in the 1335 document that mentions Paolo Veneziano, the notary included a reminder that he owes a different artist money for painting a griffin on his family crest. Painters could also create designs for embroideries, as Paolo Veneziano is known to have done. He is also likely to have created the decorations for an annual civic festival. Scholars have also attributed frescoes to Paolo Veneziano. Specific details seen in his altarpieces are very close to the figurative styles seen in contemporary mosaics.

When is the earliest date that an American museum acquired a work by Paolo Veneziano?

“The Seven Saints” were purchased by the Worcester Art Museum in 1927, making them the earliest museum acquisition of a work by Paolo Veneziano. They can be seen in the Getty installation forming the wings of the triptych reconstruction. Interestingly, in 1870 a small panel showing the “Betrayal of Christ” was donated to the recently founded University of California by the French Èmigré Francois Pioche, who had become wealthy as a financier and real estate developer. At the time the painting was thought to be by a Sienese painter. An attribution to Paolo Veneziano was recently proposed.

Bad news that the pandemic kiboshed the exhibition at the Frick. But the Getty presentation went ahead, closing October 3 in Los Angeles. Tell us how this focused exhibition, reuniting panels that once formed a larger ensemble, fills in what is known about Veneziano.

The exhibition makes a strong contribution to the study of Paolo Veneziano by settling the question of the Avignon panel’s relationship to the triptych reconstruction. Works in other media included in the installation, such as a Fourteenth Century silk textile, an ivory triptych that has the same format as the Parma altarpiece and an illuminated manuscript leaf give visitors to the exhibition the opportunity to experience the material culture of the period in which Paolo Veneziano lived and worked.

Paolo Veneziano (circa 1259-1362) and Giovanni Veneziano (active 1345-1358), “The Coronation of the Virgin,” 1358, tempera on panel, 43¼ by 27 inches. The Frick Collection, New York City. —Joseph Coscia Jr photo

Adventures of an art history PhD candidate? Can you share?

Traveling to see works that are still in the churches or small towns for which they were commissioned is always a thrill. For my dissertation research, I needed to see an altarpiece that I had read was in the cathedral of Krk, Croatia. After a series of bus rides from Venice that took more than eight hours, I arrived in Krk, and was relieved to find the cathedral still open. A sinking feeling, and dismay, when I wandered through the church: no altarpiece! I ended up attending the evening mass. I followed the priest to the doorway of the sacristy after the service and was relieved to discover that he was both friendly and fluent in German, which I also speak. When I explained why I had traveled to the cathedral, he arranged for me to return the next day to see the altarpiece, which was typically kept in the bishop’s chancellery.

To prepare for the exhibition, I visited the storerooms of several textile collections. The Cleveland Museum of Art has a very important collection of this material. Thankfully, they make high-quality images of the textiles freely available on their excellent website. I highly recommend spending time with it.

In the exhibition catalog, an example from the Deutsches Textilmuseum of Krefeld, Germany is illustrated because it is especially close to what is seen in Paolo Veneziano’s paintings. When I visited Krefeld, I found it to be a beautiful small city with a large English-style park. The local historical museum had an ancient Roman merchant’s barge that was excavated from the banks of the Rhine when a harbor was expanded in recent years. Krefeld has an important collection of silk textiles because the city was home to factories that were specialized in weaving silk clothing labels throughout the Twentieth Century – picture the kind of large labels with fancy script that you would find in a vintage coat. Local benefactors believed that assembling a collection of important historical examples would inspire the local work force. Had I not studied Fourteenth Century textiles for the sake of finding new ways to approach the art of Paolo Veneziano, I never would have visited Krefeld and learned about such fascinating local histories.

-W.A. Demers