Down in Atlanta, the High Museum of Art is commemorating one of the city’s most celebrated Twentieth Century artists, Nellie Mae Rowe. With color bursting from every inch of paper, more than 60 of Rowe’s works come together in “Really Free: The Radical Art Of Nellie Mae Rowe,” on view from September 3 to January 9, 2022. The show’s curator, Katherine Jentleson, argues that Rowe’s art crosses dimensions on the regular: two-dimensional works inspired by three-dimensional environments and vice versa. Her environment, The Playhouse, the greatest three-dimensional work she ever made, was lost to development – its existence recorded only in two-dimensional photographs. If it’s all confusing, worry not: this kind of back and forth between time and space is essential to understanding Rowe and the work she created.

The High recently got a gift of Nellie Mae Rowe works, are they included in the exhibition?

Not all of them. We received an incredible gift of 17 Nellie Mae Rowe works from Harvie and Chuck Abney. They are incredible collectors who bought work out of her first gallery show and continued to patronize her. In the exhibition there are five works from the Abney collection that we’re excited to feature. Chuck had a real eye for Rowe’s work, he collected pieces that are representative of the spectrum she was capable of and different dimensions of her artistry. Out of all the artists he collected, she was the one he engaged with most deeply.

The rest of the show is based on a series of gifts. We started collecting Rowe in 1980 but we got a major gift in 2003 from Judith Alexander. She left the museum more than 130 artworks and had already been giving us works since 1998, she basically made a gift that would make the High the main caretaker of Rowe’s legacy and we have been putting on shows of Rowe since 2005.

Where should we begin with Rowe?

The birth of her artistic profile begins in childhood with her dollmaking. She loved making art as a child, and she owned work she did as a child, but she put all that aside at some point. She grew up on a farm as one of ten children and had to help out. She got married very young and quickly upon moving to Vining, a more urban suburb of Atlanta, she took on domestic work to supplement her family’s income. She did that for more than 30 years. Her husband died, she got remarried and ends up at her permanent home in 1936. In 1948, her second husband also passes away. At that point, she starts making a little more, she draws here and there and starts hanging things.

Is that the beginning of her environment, The Playhouse?

It’s not until the late 1960s, when her longtime employers, the Smiths, have both died. Many people have started dating her rebirth to 1968. That’s when she gets to start “playing in her playhouse.” This is when she starts becoming an artist to the public, decorating her yard, inviting people other than her large family into her home. In the early 1970s, she starts getting photographed by Judith Alexander Augustine, the younger cousin of Judith Alexander, and Melinda Blauvelt, another photographer. By 1971, her home is fully decorated.

Does she have much work dated prior to 1968?

She has some drawings in our collection that are dated prior to the 1960s, but very few. The vast majority isn’t dated at all, so we might have more work that predates 1968, but she didn’t date her work until she started working with Judith Alexander. We broadly date the work we think is early.

She starts gaining attention in the 1970s, what happened there?

A 1973 article in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution brings her recognition, people start visiting her. In 1976 her work is included in “Missing Pieces,” a bicentennial exhibition that put Southern folk art on the map. It’s really one of the first shows that includes Southern folk art in the broader canon of folk art. At that show is the first time Judith Alexander sees her art, but she doesn’t take it seriously until the 1978 exhibition at the Nexus Gallery, which included Rowe’s dolls. Alexander wanted to represent Rowe immediately. She has her first show with Alexander that year, and then in 1979 she gets her first show at Parsons/Dreyfus Gallery as she makes her first trip to New York City – as far as we know it was her first airplane trip. They have this adventure in New York City, which was documented by a photographer. Her career is starting to explode, the High acquires her in 1980 for the first time. In 1981, she is diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a kind of cancer. She continues to produce, so a lot of the works we have are dated through 1981, 1982 and she passes away in October 1982. That was the year her work received broad attention when she was featured in “Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980” at the Corcoran.

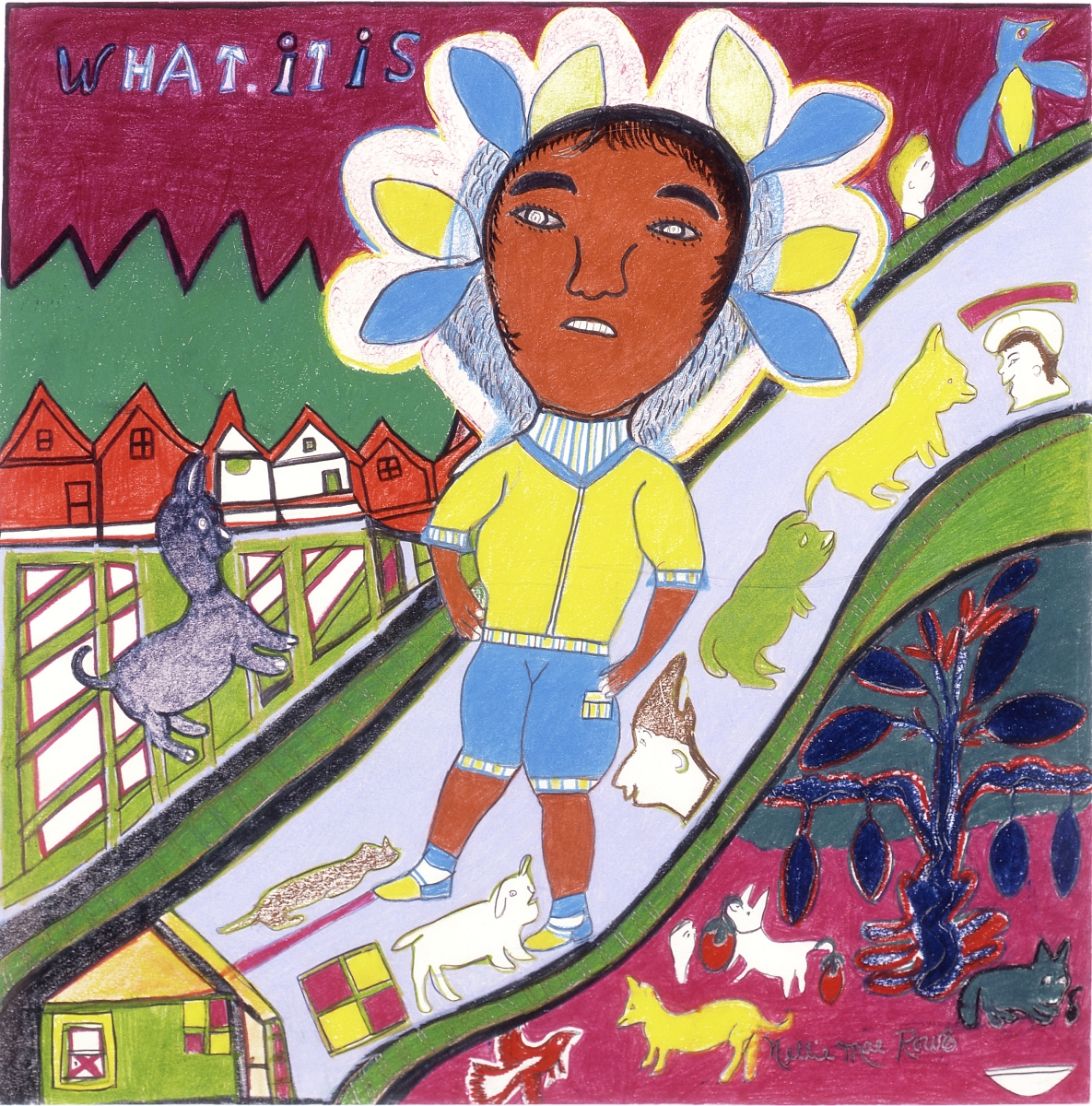

“What It Is” by Nellie Mae Rowe (American, 1900-1982), 1978–1982. Crayon, colored pencil, and pencil on paper. Gift of Judith Alexander, 2003.215. © 2021 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

What happened to The Playhouse after she died?

She was a very involved aunt with lots of nieces and nephews in the area, but no kids of her own. Her second husband, Henry Rowe, had children. My understanding is that the property was owned by the family but I think there was tension between Nellie and those children, and I don’t think there was interest in preserving what she created there. Even if there had been, the property values in Vining were skyrocketing. There is a hotel there now and there’s a tree that has a memorial plaque. Inside the hotel is a nice little display, mostly photographs but also a few drawings. So The Playhouse exists in memory and we’re bringing it to life in the exhibition.

How important was the act of playing to her process?

Everything she did in art was a form of play. There are so many male artists, whether Mike Kelly, or Kandinsky or Picasso, that their embrace of childhood is seen as sophisticated. Whereas Rowe has not been fully honored for her elevation and return to childhood. This was a specific choice, she reveled in play as an experience that she never really had.

Why are her dolls significant?

She made drawings as a child, but she also made dolls. She would take the dirty laundry laying around and transform them into dolls. Her mom was a seamstress and quilter. There’s a couple different functions of them apart from harping back to her childhood – it was also a way to keep her company. She was living alone for the last 40 years of her life. Having these dolls, some of which were on the larger size and as big as a toddler, they were a kind of comfort to her. She made them in the image of herself and people she knew. She also called them her children, which was revealing, as she did not have children. We don’t know the circumstances, but she was the only one of her sisters who didn’t have children. That was a hardship in her life. She also said things like, “God didn’t give me that gift, but he gave me this gift to create art.”

There was a tension between childbearing and rearing and being able to dedicate yourself to art. She said more often than not that she wished she had children, but dolls were another way of bringing them close. They struck a chord with Alexander, there’s an intersection between what she was doing and what feminist artists were doing in the 1960s and 1970s – around the Pattern and Decoration movement and the intersecting artistic practices usually associated with domestic labor. She had a connection with Betye Saar, who came to Atlanta quite a few times and visited with Rowe. Saar sought her out, went to visit her and still keeps a drawing of Rowe’s in her studio. What Rowe was doing with dolls had a connection to contemporary aesthetics.

Are the works in The Playhouse different than her others?

One thing that I’m trying hard to make people see is the relationship between her two-dimensional and three-dimensional practices – the drawings and the environment. There was a lot of coded meaning in her work, but there was a lot of basic correlation between what she surrounded herself with and her drawings. Photographs of the playhouse show hanging dogs, exploding trees, these are things in her work. I’ve come to understand her work as different parts of a whole. Her drawings are really related to what she was doing in space.

She hung her drawings on the walls, she put her dolls in chairs, she put her gum sculptures around. She was really using mass produced goods that people would have thrown away to create these installations – they’re not original objects she made from scratch. Around her bed she curated this display of family photographs, novelty clocks and tchotchkes and an album that was released to commemorate the March on Washington. She curated these installations with objects she valued. Dolls were everywhere, not just ones she made, but she hung them from the wall, from the window frame, a tableau. She lived there, it was a constantly evolving artwork. There wasn’t any one version of it that was final or static, it was a living breathing evolving art installation that she made. Her yard was decorated with garland, on which she hung all kinds of things: ornaments, plastic fruit, children’s toys. There are theories that these yard displays may relate to different spiritual practices in Congo and other parts of Africa. Her yard was part of that African American yard aesthetic.

How many specific installations do you think she made in her home?

I have no idea, but every surface was covered. She was a curator, she just enjoyed making pleasing arrangements of things. She said she liked being employed by the Smiths and they would let her place things at their house. From what I’ve seen in the photographs, every inch of wall space, nearly all the surfaces, everything had a very intentional arrangement.

.jpg)

“Nellie Mae Rowe” by Melinda Blauvelt (American, born 1949), Vinings, Ga., 1971. Gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the artist, 2021.69. © Melinda Blauvelt.

Is there a stylistic timeline to her work?

We have one from 1947, another from 1953 and another from 1964-and many that are undated that are from those decades, probably. Again, she didn’t start keeping her drawings until the late 1960s. In the early works, she was drawing freeform and groups of figures, they weren’t very complex. She was doing it all on different kinds of substrate or recycled paper, or a cardboard food carton. Her work was oftentimes crayon or pencil and pen. She continued to use crayon for her entire career. There’s pencil and gouache after she meets Judith Alexander, who supplies her with better materials. From 1978 to 1982, works are a larger format on archival white drawing paper, but still she preferred crayon, wax-based crayon. She was just incredibly tactile with the crayon, she would create rich ranges of color. I think it was easy for her to control, she got so good at it. We thought for some time she was using colored pencils, but she was using crayons sharpened to a fine point. When she starts getting access to better materials, her imagination explodes. Her compositions become fully decentralized in incredible quilt-like ways, the way they harmonize all these different shapes and fragments in activity. Her mature work in the last four years, there’s an incredible pictorial harmony, not leaving a single inch of the paper uncolored or undecorated. I link this to her three-dimensional practice: abundance, more is more, that’s the way she worked in The Playhouse and on paper.

You’ve linked her work with an aspect of liberation and self-expression in the post-Civil Rights era, tell me about that.

Rowe is somebody who experienced the Twentieth Century. She grew up on a rural farm in Georgia in the segregated South. She lived the trajectory of so many women: she married young, had to become an earner, and then spent her whole life working in that sphere. The fact that she started outwardly expressing to the world that she was an artist in 1968, the same year Shirley Chrisholm is elected the first Black congresswoman, the same year as Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination – this is significant. It was absolutely a response to the political shift she was living through. The point we’re making in the exhibition is that she made a choice to be a Black woman living alone in the South, in the Atlanta suburbs. As much as Atlanta was integrated, the city emerges in this moment as a beacon of the new South with a vision of a future, but the reality for the people who lived in the city was a revival of the KKK in Stone Mountain and white supremacist governors. She chose to become visible in the same year as the climax of the Civil Rights struggle.

Are there common subjects in her work? Religion? Hybrid figures?

There’s lots of different kinds of subjects. Animal symbols, frequent appearances of dogs, which have been read in the past as avatars. She didn’t own dogs, but this is a common thing you’ll see often with her works. She had so many stuffed dogs in her home and yard, she kept them all around. It’s not that I’m doubting there were more layers, but she just loved dogs. She might have believed in the symbolism of protection that dogs bring.

Another symbol that has been linked to her religious nature is the fish. It’s a major Christian symbol, but it’s also a folklore symbol about wishes for fertility. There was an idea that before you become pregnant you have a dream about fish. Some of her work with fish has erotic features in them, forms that had reproductive imagery coded as plant life in the fish drawings.

Those are her two most dominant symbols, but people are by far the most common. Women, mostly women I believe she based on herself at different stages of her life.

There’s also lots of crosses, though I think that is a reference to a historic African American cemetery just up the hill from her house. I think that when a cross appears in her work, it’s not just a symbol of Christ, but also a way to memorialize her husband and other people she cared for who were buried just up the hill from where she lived.

Your favorite work?

I love “What it is,” she made that over and over again. The phrase is a way of saying “What’s Up?” but it’s this funny thing she does. She likes to change the meaning of her work. She’d say in interviews, “People ask me all the time what the meaning is behind my work, I tell them, ‘it is what it is.'” She was amused by this interest that arose in her work, she totally knew what they meant. So that phrase is there on the work, and it’s a portrait of herself as a young girl, her braids are flowing around her in a halo and she’s walking along Paces Ferry Road. It’s just a work that really symbolizes her return to girlhood and the power to return to that.

-Greg Smith