The December 3, 2019, discovery of skeletal remains beneath an Eighteenth Century home in Ridgefield, Conn., launched a flurry of calls – to the local police department, the selectman’s office and state medical examiner. Not to worry, folks, it turned out not to be a modern crime scene. The bones were deemed to be old. Really old. In fact, the discovery and ongoing investigation may mark the first time in state history that soldiers from the Revolution have had their remains recovered from the field of battle. Among the expert team called in to provide historical context for the discovery was former Ridgefield resident, historian and author Keith Marshall Jones. We caught up with him to see if he could flesh out the findings so far.

Can you describe briefly the “scene” revealed by the homeowner’s renovation project?

The email from Sharon Dunphy, president of Ridgefield Historical Society, thrilled me to the bone! Three intact skeletons were discovered during the basement expansion of a late Eighteenth Century structure along the village’s historic Main Street. They were but some 50 yards from site of the April 27, 1777, Revolutionary War “Battle of Ridgefield.” Would I, Sharon asked, help to determine if they were battlefield casualties?

What certainty do you have that the skeletons are Revolutionary War soldiers?

Forensic testing by a team under the direction of Nicholas Bellantoni, emeritus Connecticut state archaeologist, determined the trio were strong young males dating to the Eighteenth Century. Accompanying the remains were brass and pewter buttons and a leather neck-stock representative of period military garb. Further DNA testing and forensic analysis of these artifacts – along with an accompanying textile remnant – is necessary to confirm military attribution, but it’s fair to hypothesize that the skeletons were indeed connected to British Major General William Tryon’s Danbury Raid of April 26 -28, 1777. My comprehensive account of the expedition’s Ridgefield component (Farmers Against the Crown, 2002) identified eight specific fallen patriots whose final resting place was unclear. Could the skeletons be them?

What connection would they have to that battle?

The third and chief engagement of the 1777 action at Ridgefield took place around a barricade hastily erected by 500-600 soldiers under Continental General Benedict Arnold and Fairfield County militia General Gold Selleck Silliman at the north end of Main Street. If they could delay Tryon’s 2,000-man expeditionary force long enough, a hornet’s nest of Connecticut militia and New York Continentals were on the march to overpower the invaders. Alas, these reinforcements arrived too late; but when the British stormed the barricade to take Ridgefield, at least 13 patriots were killed, four of which were officers. Formal British reports detail 30 rank and file killed, 97 wounded and 28 missing; no officers died, but 14 were wounded. These figures, however, were for the entire three-day expedition, so it’s unclear exactly how many British and Loyalist soldiers perished at the Ridgefield barricade that 27th of April. A nearby granite marker, installed in 1890, commemorates “Eight Patriots Who Were Laid In These Grounds Companioned By Sixteen British Soldiers.” Because it was erected along Main Street more than a century after the fact, this marker is purely commemorative rather than an exact burial site. The bodies were most likely, in my opinion, buried hastily in multiple graves near where they fell.

So, American or British?

While we do not know the precise military unit affiliation of individual dead soldiers, records show that the following units incurred casualties in the Ridgefield action: patriot forces: 3rd, 5th and 6th Regiments of the Continental Line – who may or may not have been in uniform; 4th, 9th, 13th and 16th Regiments of the 4th Brigade of Connecticut Militia (Brigadier General Gold Selleck Silliman); 3rd Westchester (County, New York) Regiment Militia Crown Forces: 4th, 15th, 23rd, 27th, 44th and 64th Regiments of Foot, 4th Royal Artillery and the Prince of Wales American Volunteer Regiment – approximately half from Connecticut.

We also know that it was British protocol to bury their own dead on battlefields on which they were victor, and that uniforms were often stripped from the bodies in order to preclude looting of regimental property. Patriot dead, especially militia, would have been left for the locals to identify and inter.

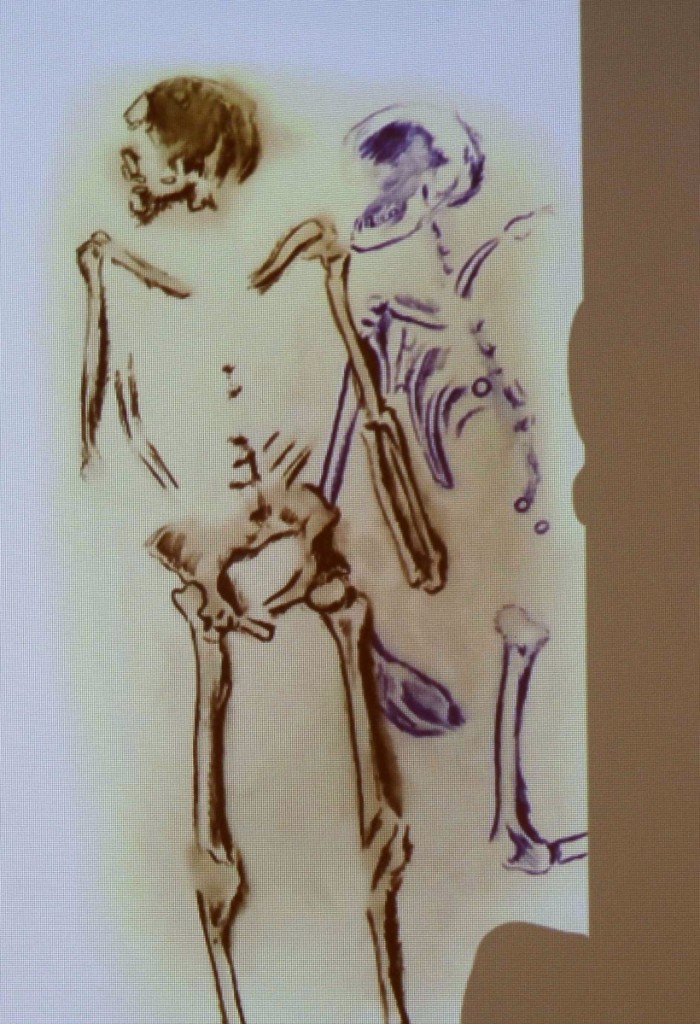

This composite sketch shows two of the discovered skeletons, which were co-mingled, one on his back. The robust adult men were lying in an east-west orientation (customary of an Eighteenth Century Christian burial) in a grave that appears to have been hastily dug. The two skeleton remains were not clothed.

What do you make of the composition of two of the remains: co-mingled, apparently not clothed and lying in an East-West orientation?

This suggests a hasty, Christian burial, whereby the graves face east toward Jerusalem and the second coming of Christ. The five brass and pewter buttons aligned on one of the two remains may be of either civilian or military nature. Rank and file of both sides wore pewter buttons. Regimental coats of both sides sported two to three dozen buttons; therefore, only five surviving buttons suggest the bodies may have been stripped down to small clothes for burial. Further forensics are necessary to determine whether the skeletons were British, provincial American volunteers, Continental Army, Connecticut or New York Militia, or perhaps just local patriots – like Salem, N.Y., farm boy David Selleck, who grabbed a musket and fell in with the militia.

Could there be more grave sites near the vicinity of the battle?

The 24 men commemorated by the Main Street marker were most likely not buried together, but rather were hastily interred by both sides in the barricade surrounds. The three skeletons, then, are probably part of this scattered collective grave site. And because the battle, after the barricade was breached, became a running street-fight throughout the village of Ridgefield, it’s likely that other unmarked graves exist around town. For example, at least one Crown soldier lies buried in a communal grave at Olde Town Burying Yard at the south of town.

Will you be rewriting your 2002 book?

The book is now in its third printing (2002, 2008, 2014). I look forward to a fourth printing of Farmers Against the Crown after the mystery of the three skeletons has been settled definitively. The book is available in Ridgefield at “Books on the Common,” on Amazon, or from my website – www.keithmarshalljonesiii.com. My fourth book, John Laurance, The Immigrant Founding Father America Never Knew, published this summer, has earned the John Frederick Lewis Prize as “Publication of the Year” by the American Philosophical Society (Est. 1743).

You now split your time between New York City and Arizona. What lured you away from Ridgefield?

As a writer I believe that each of our lives is an unfinished book, and after 26 years in Ridgefield it was time to explore another chapter. In so many ways, however, I can never leave Ridgefield…memories, friends and skeletons summon me back.

-W.A. Demers