We still don’t know everything about Fern Coppedge, but one thing we do know is that the Pennsylvania Impressionist was hard as ice. And now we know a lot more about her since Les and Sue Fox have written the first in-depth exploration of her life in Fern Isabel Coppedge (1883-1951), out November 2021 at www.ferncoppedge.com. Picture a stalwart and undeterred woman in the male-dominated art world of the early Twentieth Century as she laces up her boots, pulls on her bearskin coat, trudges through a squalling blizzard, ties her canvas to a tree and begins to paint works of art that are now regarded as some of the finest to ever come out of the Keystone State. Tell me that doesn’t change the meaning of en plein air for you.

How much research has been done on Fern so far?

L: The Michener Museum put out 48 pages in 1990 alongside an exhibition at that time. Then ten more pages in The Philadelphia Ten: A Women’s Artist Group 1917-1945. Fern Coppedge has been glossed over, no one has ever done a lot of research, mostly it has been images. We were told we’d never be able to get enough material to write a book, but as you can see, we found a lot at 262 pages.

Who did you talk to and how long did it take?

L: The first person we contacted was Michele Stricker, the author of Fern Coppedge: A Forgotten Woman, the book that accompanied the Michener exhibition. She’s now the deputy state librarian of New Jersey. She basically said there’s nothing else to research unless you can get in touch with the family. That’s what we did next, which wasn’t easy because Fern didn’t have children. Four sisters and one brother who lived to adulthood, another brother who died at age 10. We eventually tracked down ten great nieces and nephews.

S: It was a labor of love that took two to three years. I’m a trained researcher and Les is a real digger, we love doing research.

Even today it still seems like there’s often a sense of forgottenness applied to Coppedge. Why is that?

L: Alan Goldstein, the curator of the 1990 exhibition at the Michener, stated Fern was ignored and rejected by the Bucks County artist community because she dared experiment with her personal use of color. In other words, Impressionism is supposed to be what they see in a way that catches light. If Fern saw a house that was painted brown, she might paint it pink. She would paint the same picture over and over and change things. They didn’t like that, they thought she wasn’t playing by the rules. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Bucks County artist community was a male-only club. Despite that, she’s among the most sought-after of those artists today.

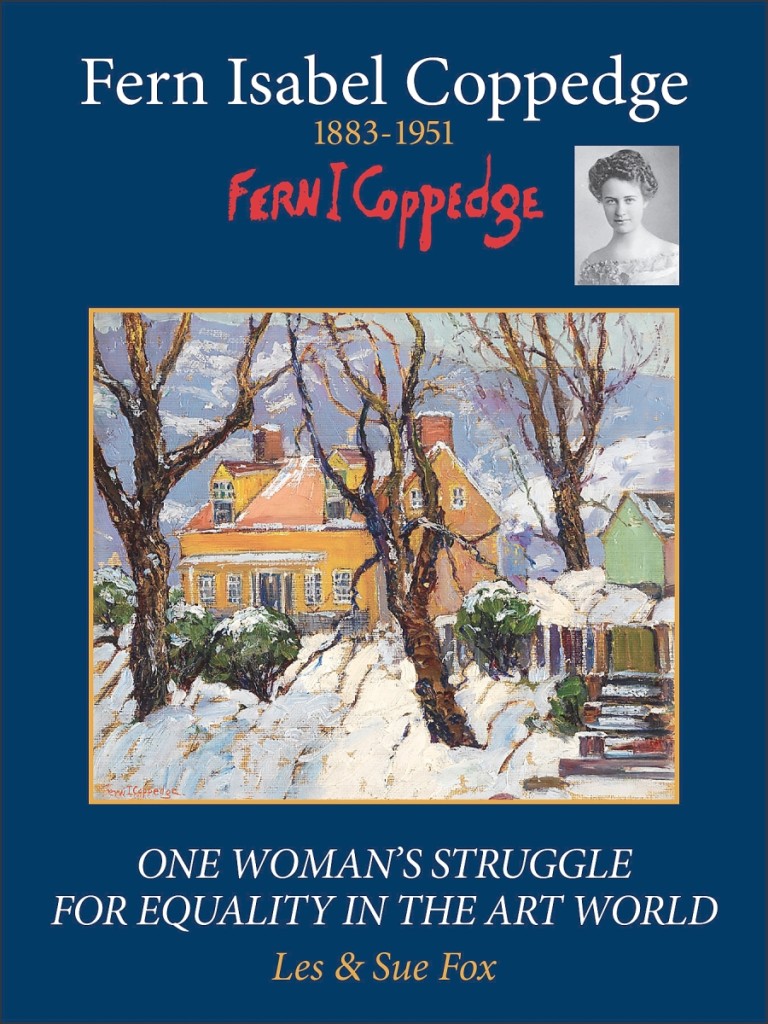

Fern Coppedge (1883-1951), the first in-depth exploration of the artist’s

life and work, is out November 15 for $65 at www.ferncoppedge.com.

Do we learn anything new in your book?

L: No one ever really dove into her marriage and personal life. Everything prior said she was married in 1910, but we’ve located her marriage certificate to her husband Robert, it’s from January 2, 1904, as well as the announcement in the newspaper for the wedding in the family house. Another new point is that she lived across the street from Daniel Garber’s cottage and studio in Lumberville called Bittersweet. She painted 30 pictures of his studio.

S: She never had a journal we found and titled few of her paintings. In the Philadelphia 10 book, the author Patricia Sydney said it was an art historian’s nightmare to figure the paintings out. In some respects, because she wasn’t wealthy, if someone loved one of her paintings, she would repaint it in a similar fashion. If she could sell a popular painting two or three times, she would. So if you look through the images in our book, there are seven or eight paintings that look very similar.

Tell me about her upbringing.

S: She started her art career in her late 20s. Her family lived in McPherson, Kan., and they all went to college and became teachers, as did she when she graduated. She had already met her future husband Robert at that point and she immediately dropped out of school to get into art.

L: Her husband Robert encouraged her to take lessons. Had her family not encouraged her, she probably wouldn’t have painted. Robert got her into this art class in Topeka High School, she was older than the students but they thought she was 18, she looked younger. She had a teacher there named Iris Andrews who was trained by William Merritt Chase. She encouraged her to go to the Art Institute of Chicago.

So she started training.

L: First at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1908. She’s there for two years from 1908 to 1910. Outside of her registration card, they have nothing from her, not even a photograph and no records of who taught her. In 1910 she’s at the Art Students League of New York. There she paints with William Merritt Chase and Frank DuMond. Chase tells her she’s pretty good. In 1917 she starts renting a studio in Philadelphia and begins training with Daniel Garber at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1918 and 1919. Garber likes her, he said he didn’t think anyone understood color like Fern did. It was something no one could teach, she just understood color. When she was a little girl, she saw colors in the snow that no one else could see. People thought she was crazy, they said snow is white, but she said she saw pink, green and purple. After a while she ignored them and painted colors in snow, and Garber appreciated that.

“Back Road To Pipersville,” circa 1926-1930. Oil on canvas, 38 by 40 inches. Provenance to Robert and Mary Lillie collection. Gift to the James A. Michener Art Museum Permanent Collection, 1999.

And there in Pennsylvania she remained.

L: Thereafter she buys a house in Lumberville, Penn., across the street from Garber’s studio on the Delaware River – that couldn’t have been coincidence.

Do you think there’s more to the relationship with Garber than we know?

L: She knew him socially, nothing romantically. They were almost the same age. They were probably good friends, they had to have seen each other more than once in a while.

When does she become involved with the Philadelphia 10?

S: She joined the Philadelphia 10 in 1922 when she became good friends with Mary Elizabeth Price, at that time a famous Philadelphia Impressionist painter who paints flowers. She basically said, ‘You should join this group, we don’t think much of the way men treat us,’ and she was with them for ten years. They held 69 exhibitions between 1917 and 1925, Fern does about 15 or 20 of those exhibitions. They’re exhibiting mostly at the Art Club of Philadelphia, they let everybody in. On average a few hundred women came to those shows and paid an average of $200 per painting. The Philadelphia 10 would encourage these women, tell them they didn’t need their husband’s permission to buy these paintings, to just bring the painting home and tell their husbands they bought it. She was very happy with the Philadelphia 10, but after a number of years she grows older and starts exhibiting out of her studio and house.

Who was buying Fern’s work back then?

L: She developed a clientele from having exhibitions and meeting people in the shows. She sold a good number of her paintings to women, but men bought them too. We know someone who purchased one in 1936 and the family still has it. They would sell for on average $100 to $300 at the time. I think the most she ever got was $800. On average, a couple hundred dollars. At the time, Garber was making prints for the same price, but Fern never made prints. We have a lot of the names of the original owners who bought her work in the book.

With Robert getting summers off, they were able to travel?

L: In the summers of 1910 to 1915 she goes to Woodstock and John F. Carlson is her teacher there. He loves to paint snow and that’s when she starts getting into that. I think Frank DuMond told her to go to Gloucester, so she goes there in 1916-1934. That’s where she gets the big break of her career, a harbor scene that gets exhibited at Wanamaker’s Department Store. In 1916, Wanamaker’s was a factor in the art market. She was in a competition of 600 artists and her painting wins and gets into a publication called International Studio magazine. It was a full-page story with a picture of her painting.

“Afterglow On The Delaware,” circa 1927. Oil on canvas, 38 by 40 inches. Provenance to Newman Galleries, Philadelphia. Exhibited in “Fern Coppedge: A Forgotten Woman,” 1990, James A. Michener Art Museum.

Was she always painting outside?

L: I think she touched things up in the studio, but she mostly painted things outdoors, even in Gloucester.

Her snow scenes are iconic. What do you see as their strength?

L: To say that Fern Coppedge liked snow is like saying Babe Ruth liked hitting home runs. She didn’t hate the other seasons, but she couldn’t wait for the winter to come.

It’s 9 pm and a blizzard is outside, expected to let up around midnight. What are the odds Fern is painting in the morning?

L: One hundred percent, Fern loved blizzards. A newspaper reporter in Reading, Penn., said she could help create blizzards. The writer reported that she was coming to paint and there was going to be no snow. She said ‘When I get there, there’ll be snow.’ And there was.

I assume she liked the cold?

L: She said that in order to paint the cold, she had to feel cold. When it was windy, sometimes she tied her canvases to the tree. Her sister gave her a bearskin coat in the early 1920s but it’s lost now. And then sometimes she also took to the back seat of her car and then painted there if it was really cold.

Fern shared a vision with Grandma Moses, any indication they knew each other?

S: We think they are probably the only female artists who specialized in snow scenes, but they did not know each other.

Are there any writings about what the other Pennsylvania Impressionists thought of her?

L: None, including John Folinsbee, who lived right next to her. There’s no indication they ever spoke to each other. She was somewhat shunned, I think, for being an individualist and a woman. Garber could be a tough teacher, he told one of his female art students that she wasn’t very good so she better learn to cook.

Today, where does she stand against the more popular Philadelphia Impressionists?

L: We feel she’s just as good as Garber and Redfield. “Backroads to Pipersville,” painted around 1930, that’s as good as any Garber or Redfield. Another, “Afterglow on the Delaware,” that’s as good as any, too. She also did some mediocre paintings, and unlike Redfield who supposedly destroyed paintings, Fern never destroyed anything. If she had a bad day, she sold it for $10.

With your book, we’ve got our first catalogue raisonné on the artist?

L: It’s a biography, but the last 85 pages include more than 400 of her paintings. We guess she painted about three times that amount and we hope that when the book comes out, more people that have private Coppedge paintings will contact us.

-Greg Smith