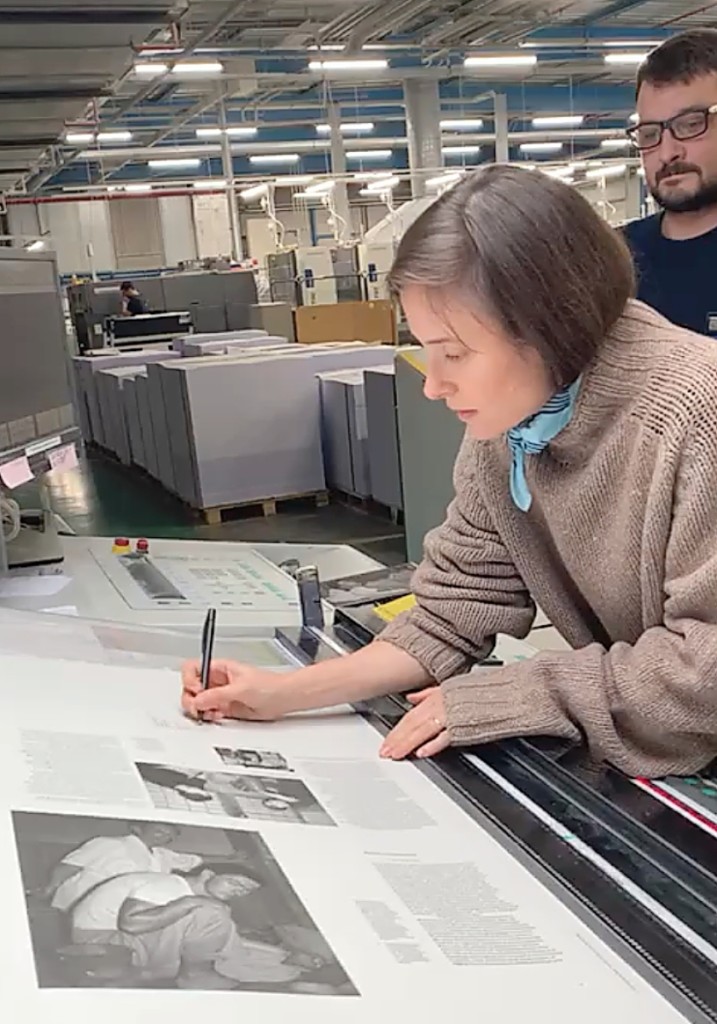

Mariah Nielson on press at die Keure for the JB Blunk book, 2020. Kajsa Stahl photo. ©JB Blunk Collection

The first survey of the ceramics and sculpture of beloved Californian artist JB Blunk (1926-2002) is out, and his daughter and the book’s editor, Mariah Nielson, is behind the move to explore the entire oeuvre of the American sculptor with previously unseen examples of his work in stone, clay, painting and jewelry. The book’s design combines archival images of Blunk’s work in situ, and his home and studio, with color plates of newly photographed pieces. We caught up with Nielson to get an understanding of the essence of JB Blunk, along with his artwork.

JB Blunk is said to have maintained a Midwestern sensibility of hard work and plainspokenness throughout his career – even as he established roots in California. Where did that come from?

His work ethic came from his humble background and intense commitment to making art – he had to make art. This determination kept him focused and productive. In Olivia H. Emery’s book Craftsman Lifestyle, the Gentle Revolution, JB said, “I just do it, that’s all.” He was an artist of action rather than words.

In addition to woodwork and ceramics, he also worked with jewelry, painting, furniture-building, bronze and stonework. What was the most “monumental” of his projects?

His most iconic artwork is “The Planet” at the Oakland Museum of California. This seating installation was commissioned in 1968 and is carved from a single redwood burl 13 feet in diameter. JB carved the giant ring with a chainsaw and the piece embodies the various aspects of his practice – the carving techniques and textures are reminiscent of his work in clay and the piece is both sculptural and functional.

What was it like growing up in a household filled with chunks of salvaged wood, sculpture and furniture in various states of completion, unglazed ceramics, wood scraps and boxes of beads and shells?

Our home is his masterpiece, a total work of art. My father made everything in the house from the furniture to the ceramic tableware. Growing up in a unique creative environment was all I knew; it was normal. The home and studio were dense environments layered with artworks and raw materials. Funny that I’ve turned out to be a minimalist!

What would a typical day for your father look like?

My father was a prolific artist and spent most days in his studio. He would have breakfast with the family, make a strong cup of black tea and then walk up to his studio. He always took a tea break at 4 pm. In one day he would typically work with several mediums – a painting, a sculpture and maybe glaze some ceramics. He often returned to his studio after dinner and stayed up late working on jewelry for my mother or loading the kiln with ceramics.

The beautiful photographs throughout the book are from your father’s archive. Who took them?

The photographs in the book were taken by friends, family and, in some cases, JB! Unfortunately, there are many photos that we can’t attribute to anyone in particular. My father didn’t keep impeccable notes or records of his work and its documentation. “Photographer unknown” comes up a lot in the book.

Why did your father travel to Tokyo, Japan, in 1951 – and what did he bring back?

My father was drafted into the Korean War soon after graduating from UCLA where he had studied ceramics with Laura Andreson. He was stationed in Korea, but in 1951, on a short training trip to Japan he coincidentally met the artist Isamu Noguchi in a shop in Ginza that sells mingei ceramics. It’s still open!

This chance encounter changed my father’s life. JB was hoping to find mingei ceramics while in Japan, specifically pieces made by Shoji Hamada. Noguchi arranged an introduction with Japanese National Treasure Rosanjin Kitaoji. After apprenticing with Rosanjin for several months JB moved on to the studio of another National Treasure, Toyo Kaneshige.

He was deeply influenced by the Shinto religion Kaneshige practiced. In an interview with Mimi Jacobs in 1973 he describes the Shinto philosophy:

“The potter that I lived with [Toyo Kaneshige] practiced Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan. The traditional Shinto religion was his way of relating to the world. Shinto has to do with reverence for what came before, not only in the animate and human form, but also in all of nature in a very complete way.”

I think my father’s reverence for nature stemmed from his years in Bizen and his time working as an apprentice for Kaneshige. The potters in Bizen source clay from the surrounding hills and allow the inherent qualities of the clay to affect the final work. Stones that are embedded in the clay body are left and the lack of glaze brings attention to the natural color and finish of the material. My father applied this way of working to all his creations. For example, when he carved redwood burls he usually left naturally occurring details within the sculpture. Often these organic forms became important features of the piece. This translation from ceramic tradition and technique to wood carving, jewelry making and painting is what I think is unique about my father’s work and what I hope the book clearly presents – the synergy and cross-disciplinary nature of his art and life.

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

This book is an introduction to my father’s work. The hope is that readers both familiar and unacquainted with JB will be presented with and surprised by the breadth of his practice and the synthesis of all the materials he worked with. For example, chisel techniques he used on sculptures and furniture were also applied to ceramics and paintings. I also hope readers will better understand JB’s background and creative influences.

-W.A. Demers

JB Blunk is available from Blunk Books/Dent-De-Leone; Hardcover, 8¼ by 10¼ inches; 226 pages/ 71 color / 73 b&w photos; list price: $55; CDN $77.]