It may be difficult to conflate the current coronavirus pandemic and cemeteries in a positive way, but Meg L. Winslow, curator of Mount Auburn Cemetery’s Historical Collections & Archives in Cambridge, Mass., and the cemetery’s nonprofit Friends have harnessed a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) CARES grant to create an innovative crowdsourcing initiative spurred by the pandemic. The NEH grant is being used to enable people working from home to gain open access to historical documents in a program titled “Providing Comfort and Inspiration: Transcribing the Records of America’s First Rural Cemetery.” Antiques and The Arts Weekly sat down with Winslow to get briefed on what the novel project entails.

How long has Mount Auburn Cemetery been operating?

For nearly 200 years, Mount Auburn Cemetery has been burying the dead and consoling the bereaved in a landscape of extraordinary beauty. Founded in 1831 as one of the earliest Massachusetts nonprofits and the first large-scale designed landscape open to the public in North America, Mount Auburn’s mission remains the same. As a National Historic Landmark and active cemetery of 175 acres, Mount Auburn serves as a beloved community resource and vibrant cultural institution concerned with human stories and expression, landscape and preservation. The grounds were designed by General Henry A. S. Dearborn, Dr Jacob Bigelow, Alexander Wadsworth and George W. Brimmer, along with members of the newly formed Massachusetts Horticultural Society. As a landscape for the living as well as the dead, Mount Auburn represented a turning point in Nineteenth Century attitudes about death, burial and commemoration. The cemetery’s concept of bringing the grave into the garden was widely imitated across the United States and inspired the great age of cemetery-building and the establishment of America’s public parks.

Who are some of the historical figures who were early visitors?

In 1860, the 19-year-old Prince of Wales, Queen Victoria’s son who became Edward VII, thrilled America with a visit that included a stop at Mount Auburn. He helped to plant two trees across from the Chapel – a European Beech and a native American Yellowwood. Emerson walked here, Robert Frost read Virgil here, and a young Emily Dickinson visited on a trip to Boston. Today, Mount Auburn welcomes more than 250,000 visitors a year. In addition to tourists and families attending burials and services, it’s a place for nature lovers, historians and artists looking for inspiration.

Can you quantify the cemetery’s archives?

The archives are the only known collection of their kind in the nation. There are more than 3,500 linear feet of records collected and generated since the cemetery’s founding in 1831. If we laid out all the boxes, they would cover the length of the road from the Entrance Gateway to the Tower. Holdings include the permanent records of the institution such as deeds, lot correspondence, invoices, death certificates, lot maintenance records, entrance tickets, trustee records and annual reports, interment records, superintendent reports, operations and engineering records, horticultural records and financial records. Also included are detailed monument plans, work orders and invoices from sculptors and carvers, examples of primary source materials that offer an extraordinary level of detailed documentation for the monument collection.

As the first rural cemetery in America, Mount Auburn must have a number of historical celebrities interred there. Who are some of the most prominent?

More than 100,000 individuals are buried and commemorated at Mount Auburn, including Isabella Stewart Gardner, James Russell Lowell, Julia Ward Howe, B.F. Skinner, Mary Baker Eddy, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Fanny Farmer, Charles Sumner and Margaret Fuller. Notable African Americans include abolitionist and author Harriet Jacobs; lawyer and judge George Lewis Ruffin; activist for women’s rights and civil rights Josephine St Pierre Ruffin; and Clement Morgan, founder of the NAACP. Sculptors Harriet Hosmer, Anne Whitney and Horatio Greenough; photographers Minor White and Slim Aarons; illustrator Charles Dana Gibson; and painter and printmaker Winslow Homer include some of the prominent artists laid to rest here.

Among the cemetery’s thousands of monuments, are there any that speak personally to you?

Typically, my favorite monument is the one I’m working on at the moment such as the Sculpture of Hygeia commissioned by Dr Harriet Hunt and carved by Edmonia Lewis, or the Amos Binney monument commissioned by his widow and carved by Thomas Crawford. There is an evocative, rectangular ledger stone lying on the ground, with a long thin cross, no name, no dates, often covered in pine needles in the shade of a side path, that I’ve always loved. It belongs to the American stained glass artist, painter and book designer Sarah Wyman Whitman (1842-1904). On the stone, it says simply: “Sursum Corda.” Lift up your hearts.

How many volunteers are at work transcribing Nineteenth Century handwritten documents?

In April we started out with three volunteers and since then, the public has jumped in to grow that number to 80 volunteer collaborators. At this point, we average more than 100 pages transcribed per week. By December, we will have completed 4,000 transcribed pages – just think of it! Now, researchers from around the world will have access to these documents. Better yet, the materials they are using will be readable, searchable and accessible. This new group of digital volunteers is just as important as our other Mount Auburn volunteers. We invite everyone to be a volunteer transcriber by joining the project at fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery.

What kinds of documents are they transcribing?

There’s a treasure trove of Nineteenth Century documents that tell the story of Mount Auburn. Meeting minutes, letters and reports detail the decisions and discourse among the founders, trustees, superintendents, sculptors, gardeners and lot proprietors relating to the daily design and care of the cemetery’s landscapes and memorials. I particularly love the stories found in the 1855 sculpture commissions, the “Sphinx” Civil War memorial, our first greenhouse and nursery, and the commission of early stained glass windows from Edinburgh, Scotland, for the first chapel.

Nineteenth Century penmanship can sometimes be baffling. Any tips?

Reading Nineteenth Century handwriting can be quite difficult at first, but once you get used to it, it can be rewarding and enormous fun. For example: The “long s:” Transcribers will likely come across a letter that looks like an “f” but is in fact a long “s,” reflecting the handwriting style of the time. It looks like “Mr Rufsell” but is in fact: Mr Russell, the cemetery gardener in 1834. It helps to know that “Messrs” means misters, and that “viz” and “to wit” both mean namely, or, that is to say. There are also lots of abbreviations for names: Jno for John and Jas for James. And, of course, there are charming archaic turns of phrases, such as: The meeting was “holden” on such and such a date, and “do” means ditto. Etcetera was written with an ampersand and the letter c: “&c.” Transcribers have become quite fluent with a new vocabulary consisting of terminal long dashes, tildes and curly brackets.

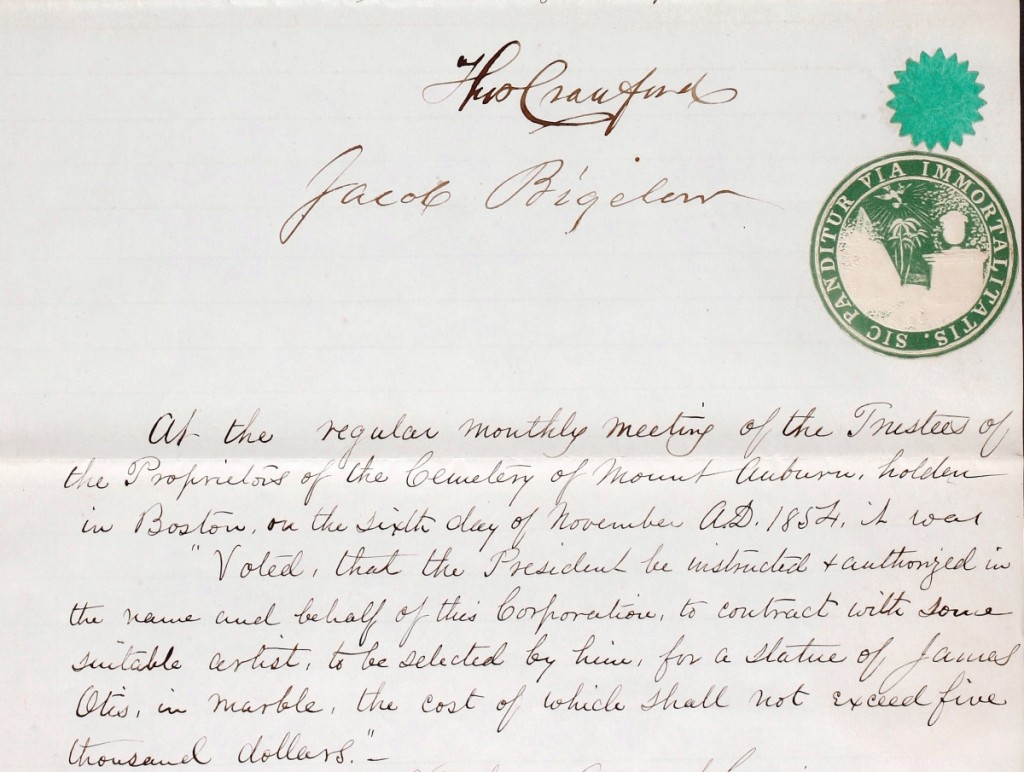

An 1855 contract between sculptor Thomas Crawford and Mount Auburn Cemetery. Courtesy of Mount Auburn Cemetery.

What has been the biggest surprise to arise from these stories of the cemetery’s early decades?

There’s nothing more exciting than the thrill of deciphering a letter written hundreds of years ago, discovering its contents, and then being able to share it with researchers and the public. I never knew we had perpetual care of soil! Or that sculptor Randolph Rogers lost his life-size marble statue of John Adams at sea – and then nearly lost it a second time! When you’re transcribing, you begin to understand the personalities of the writers. To be in the Nineteenth Century for a while, to be in their brains and see what they’re thinking has been a great escape during this time of COVID-19. The project has provided a steadiness during an unsteady time, and every day reminds me of our common humanity. I feel as though we’re making a difference for the future by sharing these voices from the past.

Can anyone with a computer and internet connection join the project?

Yes! That’s what is so great about this project. Everyone can join! Wherever you are in the world, if you have a computer and an internet connection, you can log on and start transcribing. If you would prefer, you can also look through the digital images of historic documents with their elegant handwriting and read their transcriptions. On a computer monitor, the digital image is often easier to read than the original document because you can zoom in for a closer look.

The project is obviously a boon for researchers. How does the grant impact the professional staff and volunteers?

We were thrilled to receive the announcement of our award in June. As a result, we’ve been able to secure staff salaries and do our best mission-driven work at a difficult time. The project has enabled us to work with our collections virtually, while at the same time make these historic, primary source materials available to the public. The project is already helping researchers around the world as well as enabling Mount Auburn staff to tell our own story – an expanded, more inclusive story – that is now available to everyone like never before.

We saw horrific pictures of mass burials at New York’s Potter’s Field on Hart Island early this spring as COVID-19 ravaged the metropolitan area. What does your work tell you about how Americans dealt with mass loss of life in the past, such as during the Civil War?

We see firsthand how the Victorians were surrounded by death, that it was woven into the fabric of their daily lives. Mount Auburn’s records document the high mortality rates, and the young ages of everyone buried at the cemetery. In the 1850s, for example, about a third of all burials at Mount Auburn were those of children five years of age and younger. Letters to the cemetery show how families chose to assuage their grief through artistic expression on monuments that incorporate comforting symbols of sleep and innocence. With more than 620,000 deaths in the Civil War, there doesn’t seem to be a family that wasn’t impacted. Founder and second president Dr Jacob Bigelow thought deeply about the impact of this war on the nation. His records show how he designed and commissioned sculptor Martin Milmore in 1871 to carve a monumental “Sphinx” to commemorate the end of the war, the magnitude of the events, and the greatness of their consequences. Bigelow describes his intention to create a memorial work of art to be placed at Mount Auburn for a suffering nation poised on what he called “the dividing ridge of time.”

Earlier in your career, you were an art advisor to private collectors and artists. What was that like?

There’s a rich pleasure in making connections between art and the viewer. I’m interested in what happens when we look at art, and in the experience of art. Why is it that certain works of art endure? How is it that a Nineteenth Century cemetery monument can feel relevant? Or that the combination of art in nature can be more inspiring than on its own? Art is often unexpected in a cemetery, but it is available to everyone. Looking isn’t an isolated or directed experience here. We can walk all around an object, come back to it, visit it in different seasons and times of day, linger a long time with it. Works of art nourish me visually, and Mount Auburn is a place where you get that immediate fulfillment from the objects in nature.

Is Mount Auburn open to the public now?

The cemetery grounds are open to the public every day of the year free of charge, morning to dusk. In July, the gates are open from 8 am and close at 8 pm. For a brief period in March, the gates were closed temporarily in order to protect grieving families and essential staff who were overseeing cremations and burials. We’re all grateful that didn’t last long as so many of us walk there to visit graves, have peaceful walks and find solace. Non-essential staff and volunteers continue to work remotely from home. I’m grateful that we launched our online collections database less than a year ago: www.mountauburn.pastperfctonline.com. This has helped us enormously.

You and Melissa Banta of Harvard recently profiled the cemetery’s evocative funerary sculptures and monuments in a book, The Art of Commemoration and America’s First Rural Cemetery: Mount Auburn’s Significant Monument Collection. Where can folks find a copy?

This slim volume is available on the cemetery website’s store and at the Cemetery Visitor Center for $12.50. This publication was made possible with a grant from the US IMLS to research and document 30 of our most significant monuments. Our goal in writing this book was to provide the readers with an accessible guide and give some context and vocabulary to better understand our collection of significant monuments. Mount Auburn was the first cemetery to receive such a grant.

Would you like to be among the company of souls at Mount Auburn when your time comes, and if so, what would your monument look like?

Yes, I can’t imagine being any other place. Wouldn’t that be great company?! Can you imagine sitting at each grave and listening to their stories? I do love the idea of giving my boys a place to go, to remember, a place to touch. We’re thinking about sustainability so much these days, stewardship of the land and green burial. It could just as easily be a tree or a boulder. It’s the landscape of Mount Auburn in its entirety that serves as memorial.

What do you want people to know?

With volunteer help, a wealth of new content will be unlocked and made available to everyone – providing new insights into America’s first rural cemetery and the first designed landscape open to the public in North America. I no longer think of our history as remote and fixed. Instead, it is expanding and opening up with new voices. With this project, we are filling out the story of Mount Auburn and making it available as never before. The effort helps us better understand our past but also our present. I believe we all want to feel useful and make a difference. This project is just one of many ways to help out. Please join us at www.fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery. Browse our collections at: www.mountauburn.pastperfectonline.com.

–W.A. Demers

-1024x940.jpg)