Collector Mitchell “Micky” Wolfson Jr is a man of action. His sprawling 155,000-object collection is housed between two eponymous museums on opposite sides of the Atlantic, the Wolfsonian-FIU and the Wolfsoniana, both of which still receive a steady stream of objects and scrawled notes from the collector who has no intention of stopping. Curators at the Wolfsonian-FIU have launched an exhibition to tell Wolfson’s tale: “A Universe of Things: Micky Wolfson Collects,” on view for a year beginning November 15. Wolfson’s endeavoring mission is unique in quality, scale and theory among his peers, so we caught up with him, on the occasion of his 80th birthday year and in the midst of a trip through Bulgaria, to listen to but one chapter of his monumental story.

Tell me about the Wolfsonian-FIU and The Wolfsoniana’s mission. Where in those missions do we see the collecting and personal spirit of Micky Wolfson?

They are absolutely reflections of my spirit and my methodology and my mission. We collect linguistically. I believe the language that men and women speak influences the forms men and women make. The language is the DNA. It is the relationship between the spirit and the matter that people work on. We collect in seven languages: Italian, Dutch, German, English, Japanese, Slavic and Celtic. We don’t collect territorially. We used to collect by country and now we collect men and women who speak those languages. It’s a mission of identity – the art and function of ideas. The material manifestation of the spirit. It’s a very interesting juxtaposition because I’m not a Marxist or a Leninist but I believe it’s humanity that determines man’s history and destiny. In the Eastern market, they believed economics determined everything in a man’s life. But it’s the human condition that influences and controls what we make.

What guides the collection? Do you have a favorite area?

I create mosaics. Each fragment of the mosaic plays its own role. I’ve never had a favorite. I only ever have a favorite in the moment. Only interested in the now and in the future. I’m not interested in particulars, I’m interested in the whole mosaic of objects. I don’t believe in history, or the words people say and write, I only believe in what men and women make because that’s the material manifestation of the spirit.

This exhibition does not venture earlier than pre-1850, is that specific to this exhibition or your focus in general?

I’m easily manipulated; my collection should be 1885-1945, but because I listen to the curators, they have expanded my collecting to 1850 to 1950.

Why those years?

For the ending date of 1945, the war was over, it was the dawn of my generation. My generation believed it was the dawn of a new day, though we were totally wrong. The old world didn’t finish until 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall. I like 1885 because the United States reached the GDP of the powers in Europe. It’s an interesting comparison. Though bringing it back to 1850, it should really be 1848, which was the dawn of a new age after the revolutions in Europe.

Sideboard designed by Edward William Godwin (British, 1833-1880), produced by William Watt, London, circa 1876. Pine, ebonized mahogany, silver electroplated hardware. The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson Jr Collection.

This exhibition is as much about you as it is about the objects. It is a collector’s tale. An object means everything to an owner, but how important is an owner to an object?

It’s a portrait. I didn’t write it, the curators did. They have done a portrait of me using the language of the objects that I collect. I never wanted anything but three things in life: I wanted a train and a castle and the ability to be able to travel where and when I wanted. I am not in the least bit interested in propriety. It’s easy for me to give it away and it still is. I’ve given half of it away, and I’m cautious. I have no sense of propriety, none.

Do you think you’ll like your portrait?

I haven’t seen it yet. I don’t interfere. I’ll let you know when I do. I’ll probably like it because they know me better than I know myself. And so far, since they live with the objects everyday, they know me as well as anybody could. It’s fun for me to see them do a portrait and I would never interfere. The sitter doesn’t interfere with the artist.

Where did you draw the line in the exhibition?

I always say more is best. But the curators are more practical, and they are the editors of my novel.

Any themes?

The context is history. Human endeavor, human error, human sorrow, human joy. It’s about the human condition and where we are and how we got there. So this is the moral crusade. Isn’t that a weird thing to say? But it’s optimistic and I am optimistic. I’m perfectly aware of the horrors that men can do to each other, but nevertheless human error is a constant. You can’t suppress it and undo it. So I try to make people aware of their history. Of our history. Of humanity. And my hope is that the collection and the exhibition teach tolerance, understanding, patience and somehow not forgiveness, but at least a better comprehension of how things happen and what happened and how they happen. Nothing is black or white. Everything is gray, it’s never so clear. You have to examine, life is prismatic and you have to really examine the prisms that make up the whole.

Which of the objects in the exhibition do you remember acquiring most vividly?

What I remember most vividly is what I wasn’t able to acquire.

How many objects have you contributed to the museums now?

155,000. The library has 75,000 objects, the commemorative medals has 20,000 and then there’s everything else…paintings and furniture and sculpture.

And you’ll never sell?

I’m not going to sell anything. Everything is documented and accounted for and I have a full record. And it will continue to be documented forever.

Do all of the things you own head to one of your museums?

Everything I own, the two museums have access to. Do I collect personally? No, not really. What I have where I live is what I’ve bought in the moment before it heads off to the museum for cataloging. I live with a lot of things, but it’s just decoration for the moment.

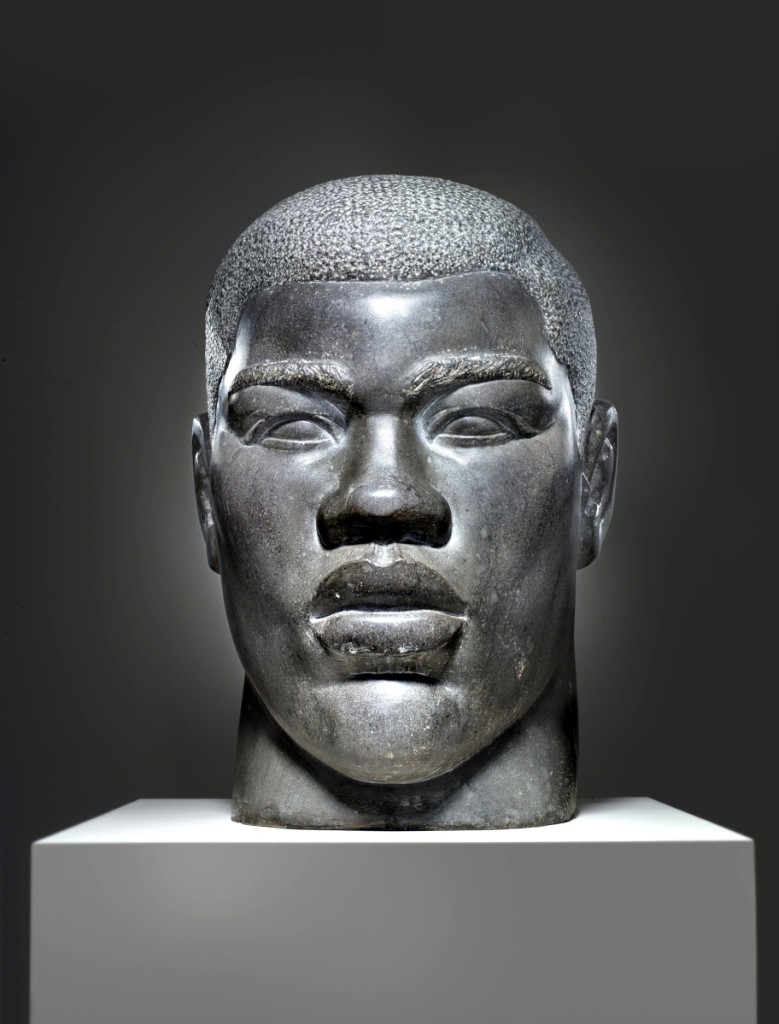

“Joe Louis” by Ruth Yates (American, 1891-1969), New York City, 1940. Marble. The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson Jr Collection.

So no personal cabinet of curiosity?

The whole thing is a cabinet of curiosity.

When I think of your collection, the sheer volume is what really sticks out to me… 155,000 objects over your lifetime means you’re buying multiple things every single day.

Yes, that’s right. Would you like to know what I bought today?

Of course.

In the Varna Archaeological Museum, which is one of the greatest archaeological museums on Earth, there’s a man who sells commemorative medals. So I got two medals from the Varna Trade Fair of 1935 and a large commemorative medal of Georgi Dimitrov. I got a pin of Russian/Soviet Communist Friendship with Stalin and Dimitrov. I bought eight books on the decorative and applied arts of Bulgaria, Bulgarian Art Deco architecture and Bulgarian design.

Do you have any advisers?

I have many advisors behind me, including my accountant and the curators. Some beg me not to buy anything and, from time to time, send out a moratorium. The museums are quite happy with what they already have. But unfortunately, there’s no hope.

The exhibition lists a model of an Italian railcar, for which you own the actual 63-foot-long Fiat railcar, La Littorina. What was your curator’s response when you told them an Italian railcar was coming?

Well you could imagine the disbelief.

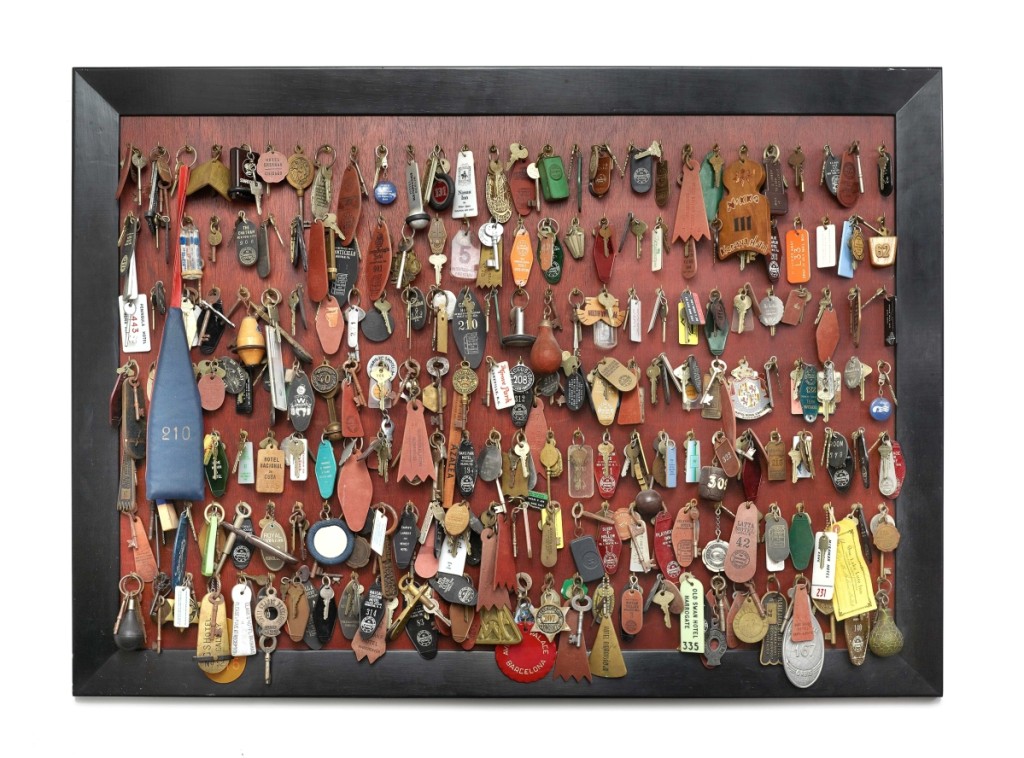

I read in the catalog that you first collected keys.

Well, as for the first thing I collected – when I was in the crib, I reached out to grab something, though I know not what. But the most articulate were the keys, because the keys opened doors. And I’m a colonialist, I wanted to know more. I wanted to open doors to men and women and to understand and grab what was around me. Those are symbolic for metaphors to open the mind to adventure and stimuli and newness.

Hotel keys, 1951–86. Metal, wood, plastic, cloth, leather. The Mitchell Wolfson Jr Private Collection.

You’re passionate about objects, but what do you personally love?

There are things I love – love, love, love. I love my Castello Mackenzie [Mackenzie Castle]. I love Asheville, N.C., where I grew up on a farm, and I love Key West. And I love my railroad train. All children want a castle or a train and I have them both.

A castle?

Castle Mackenzie, the last castle ever built. In 1914, they built it with the same criteria as the castles in ancient times. I don’t own it anymore, I just live in it – thank God. It’s got 96 rooms and a grotto, which has an original Venus de Milo work.

Most things ever purchased at once?

Oh, I think that’s easy. That would be archives. I’ve gotten them in 10,000 and 20,000 pieces. Both Italian archives, very important, and the filmmaking studios of Italy. And the archives of Schultze and Weaver, the architects who redesigned the ballroom in the Plaza Hotel, The Breakers in Palm Beach, etc. We have volumes and volumes of archival material. And among motion picture houses, we have huge archives there.

What about non-archival material?

The furniture from the first-class waiting room of the Milano Centrale railway station. I was walking through to catch a train and saw them taking it all out. I stopped and said, ‘you can’t take that out,’ and the man turned around and said, ‘Well, would you like to buy it?’ I said yes. He said rather smugly, ‘well, where would you like us to put it?’ We wound up finding a warehouse.

In 50 years, what do you hope the Wolfsonian and The Wolfsoniana will have achieved?

I only have one hope: I hope it will be a major educational resource for the applied and decorative arts. I’m not necessarily interested in it as a museum, it should be like the Bard Center in New York, an education center for students to understand the history of man. I want it to be used by as many people as possible to improve education and give people a broader understanding of our human condition and to inspire more tolerance of human changes and shifts in diversity.

-Greg Smith

_photo_by_lynton_gardiner_(2)-819x1024.jpg)