When the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester, Mass., set out to present an exhibition spotlighting archival materials from its own collection and from those of eight sister organizations, it had the good fortune to enlist Dr Molly O’Hagan Hardy, director for digital and book history initiatives for the American Antiquarian Society. Hardy not only became guest curator for “Unfolding Histories: Cape Ann Before 1900,” a show currently on view there until September 9, but also recently joined the museum as director of library and archives.

When the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester, Mass., set out to present an exhibition spotlighting archival materials from its own collection and from those of eight sister organizations, it had the good fortune to enlist Dr Molly O’Hagan Hardy, director for digital and book history initiatives for the American Antiquarian Society. Hardy not only became guest curator for “Unfolding Histories: Cape Ann Before 1900,” a show currently on view there until September 9, but also recently joined the museum as director of library and archives.

Your book covers a big swath of time: beginning with Native American life to the turn of the Twentieth Century. I see a Ken Burns miniseries here. How did you come up with the chapter themes?

The impetus for the exhibition was two-fold. First, to highlight the area’s vast archival holdings and, second, to begin to tell some of stories of people who have been underrepresented or even silenced in the telling of Gloucester history. With this second goal in mind, I went into the planning with certain themes determined, but I didn’t want to be too stringent. Researching in archives requires a delicate dance: sometimes you lead, and sometimes you are led. I had to let the archives dictate what some of the themes would be. For example, I didn’t expect to find such amazing primary documentation recording how and when the people of Cape Ann cared for each other. Repeated evidence of local security nets that various communities organized, as well as evidence of the ways in which local, state and federal government provided for those in need meant that “Charity and Welfare” emerged as a theme.

Who is this exhibition designed to appeal to?

“Unfolding Histories” aims to make early archival collections on Cape Ann known to a wider scholarly and popular audience; to both residents of Cape Ann who are proud of their history, and to the professional and amateur historian who will surely be delighted to listen to the stories these archives might tell. Gloucester is preparing to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Dorchester Company from England. The stories of those early settlers are well known, but the stories of others: the Native Americans living here, the African Americans who were enslaved – these stories are less known, so getting a more nuanced, complex understanding of the region’s history seems especially pressing now.

You let the documents tell the history of Cape Ann. Where did they come from?

The documents came from nine holding institutions, primarily the Cape Ann Museum and Gloucester City Hall, but there are objects on display from each of the other seven places where I conducted research. In Gloucester, these include the Annisquam Historical Society, the Gloucester Lyceum and Sawyer Free Library and the Sargent House Museum. In Essex, this included the Essex Historical Society and Shipbuilding Museum as well as the Town of Essex archive loaned materials. The Manchester Historical Museum and in Rockport, the Sandy Bay Historical Society and Museum, were also substantial contributors.

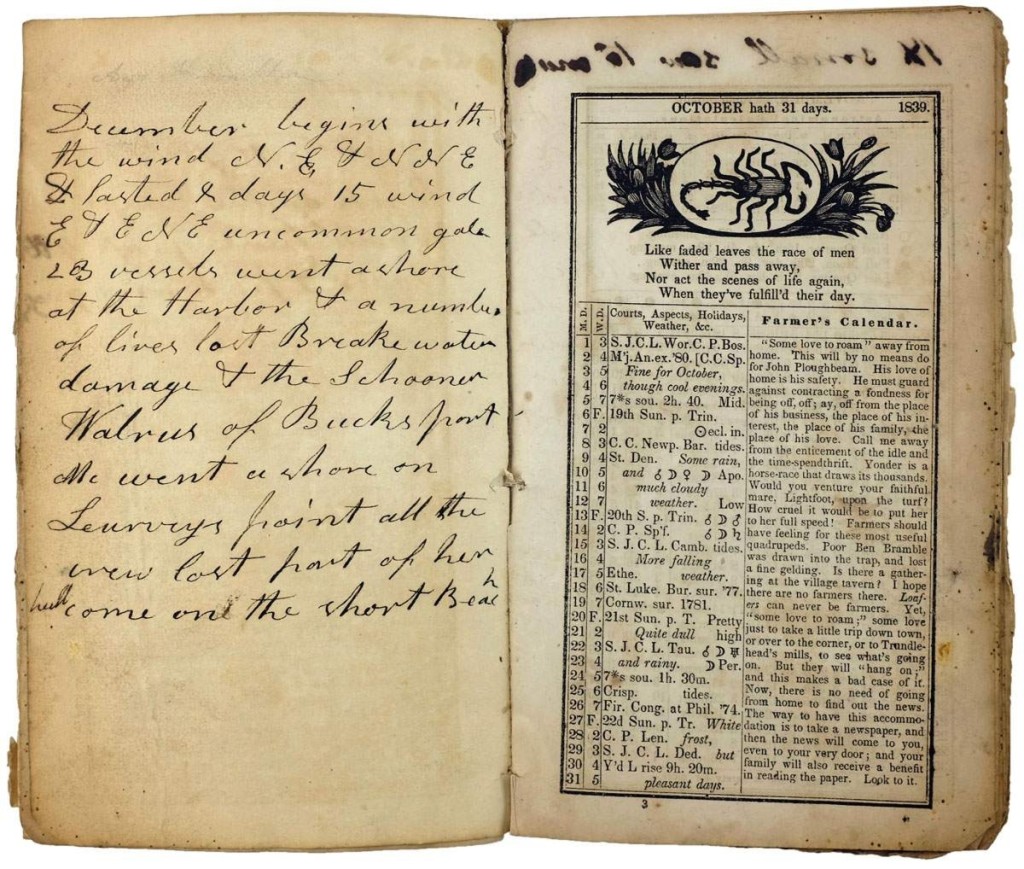

Azor Knowlton’s (b 1789) annotated The Farmer’s Almanack (Boston: Published and sold by G.W. Palmer & Co., 1838). Sandy Bay Historical Society and Museums.

Where are the biggest gaps, if any?

The biggest gaps in the exhibition reflect the biggest gaps in the historical record: first-hand accounts of marginalized people. For example, we have nothing that a Native American or African American wrote, beyond an occasional signature or mark to indicate a legally binding agreement. We have to triangulate and approximate these people’s experiences on Cape Ann, rather than be able to know them from their own voices, their own accounts.

Original documents translate easily into a book form. How does the museum’s exhibition deal with the difficulty of displaying fragile scraps of paper?

Fortunately, the crack team of exhibition mounters here at Cape Ann Museum was undaunted by this task. They embraced the archival objects, treating them as fine art paintings as they considered how to frame them, light them and lay them out. I am pleased to report that the exhibition did require that the museum purchase a number of display cases, as well as book cradles. Once the exhibition comes down, these will be put to good use in the museum’s library.

Among the book’s ten chapters, each dealing with a different theme, which one resonates most personally for you?

As a literary historian, I am rather partial to “literary imagination.” This whole project started when I began snooping around the local collections here to answer a question about an early Nineteenth Century poem. There are traces of that research in the exhibition catalog, but I am still developing it for a few presentations this summer, and then I hope to complete an academic article this fall. Throughout my research into all of the themes, there were few times when I wasn’t learning something that really excited and energized me. Cape Ann’s history is deeply local, but, given its history as the United States’ first continuous seaport, it is also deeply international and interwoven with national and international trends. To borrow a formulation from one of my favorite historians, Karin Wulf, early America is vast indeed.

You’re guest curator for the museum’s exhibition, but you also recently joined the institution as librarian and archivist. How is it going?

I am thrilled to be in Gloucester, working with these collections and making more time for my own writing and research when I am not in the library. Questions about the fate of local history in the face of uneven, but undoubtedly massive digitization are very much on my mind right now, and I so appreciate being in the trenches, not just theorizing about archives, but being confronted with the book rot, the age-old dust and even the occasional moldy spot. In the Nineteenth and for much of the Twentieth Centuries, we fetishized large, national or statewide repositories. In the age of digitization, I am less convinced that the same logic applies as collections can be brought together for study without being in the same physical location. As long as we can provide stable, safe environments for our collections as well as remote access, then there are real benefits to communities, and I would surmise, to the study of the past writ large, to keeping collections local. My new position allows me to test that hypothesis while, I hope, continuing to care for as well as to make more accessible these amazing collections.

–W.A. Demers

[Editor’s note: Copies of Unfolding Histories: Cape Ann Before 1900 are available at Amazon and the Cape Ann Museum shop].