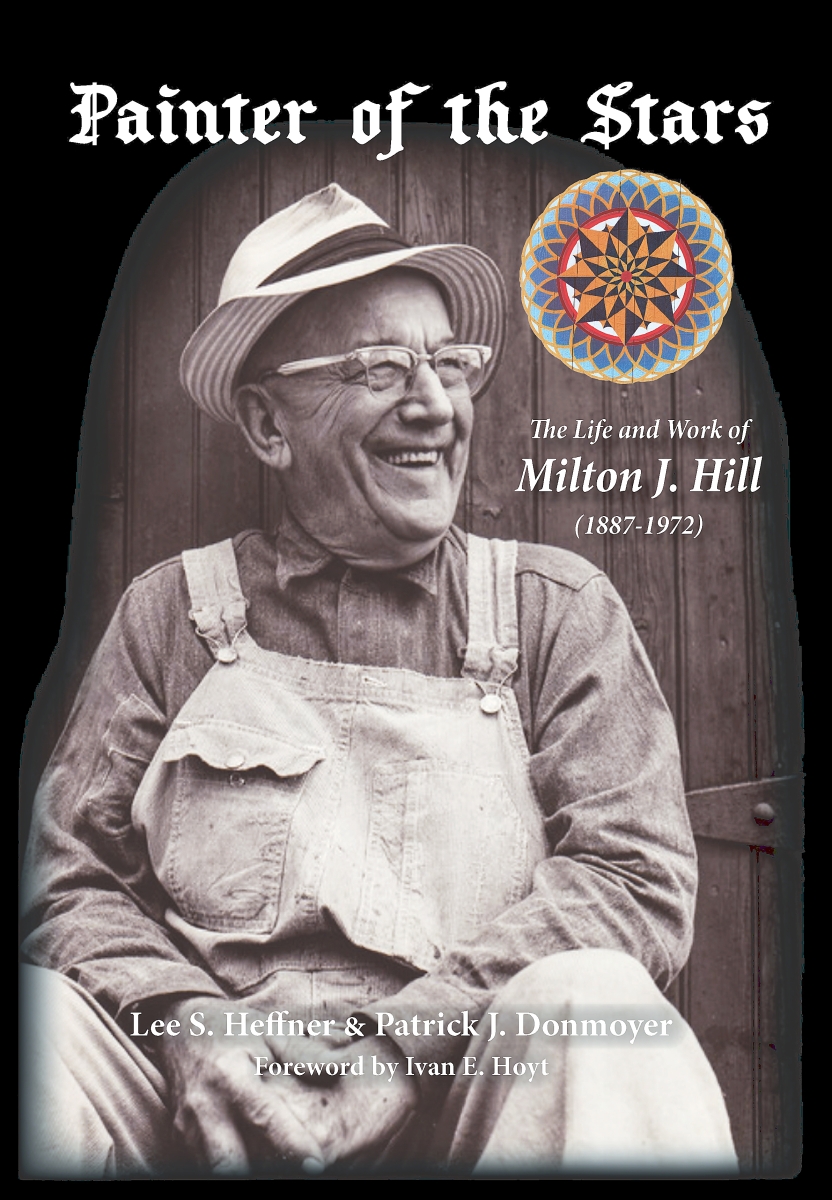

The Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center (PGCHC) in Kutztown releases a new title every year, the newest allure found in Painter of the Stars: The Life and Work of Milton J. Hill (1887-1972). By Hill’s grandson, Lee Heffner, and Patrick Donmoyer, director of the PGCHC, the book tracks one of the most well-known and prolific Pennsylvania barn star painters of the early Twentieth Century. While Hill was firmly rooted in the tradition of the folk art form, he was also an innovator who developed complex designs and inspired an entire generation of painters after him. We sat down with Patrick Donmoyer to talk about Hill, this long-rooted Pennsylvania tradition and the culture that surrounds it.

How did Milton learn to paint barn stars?

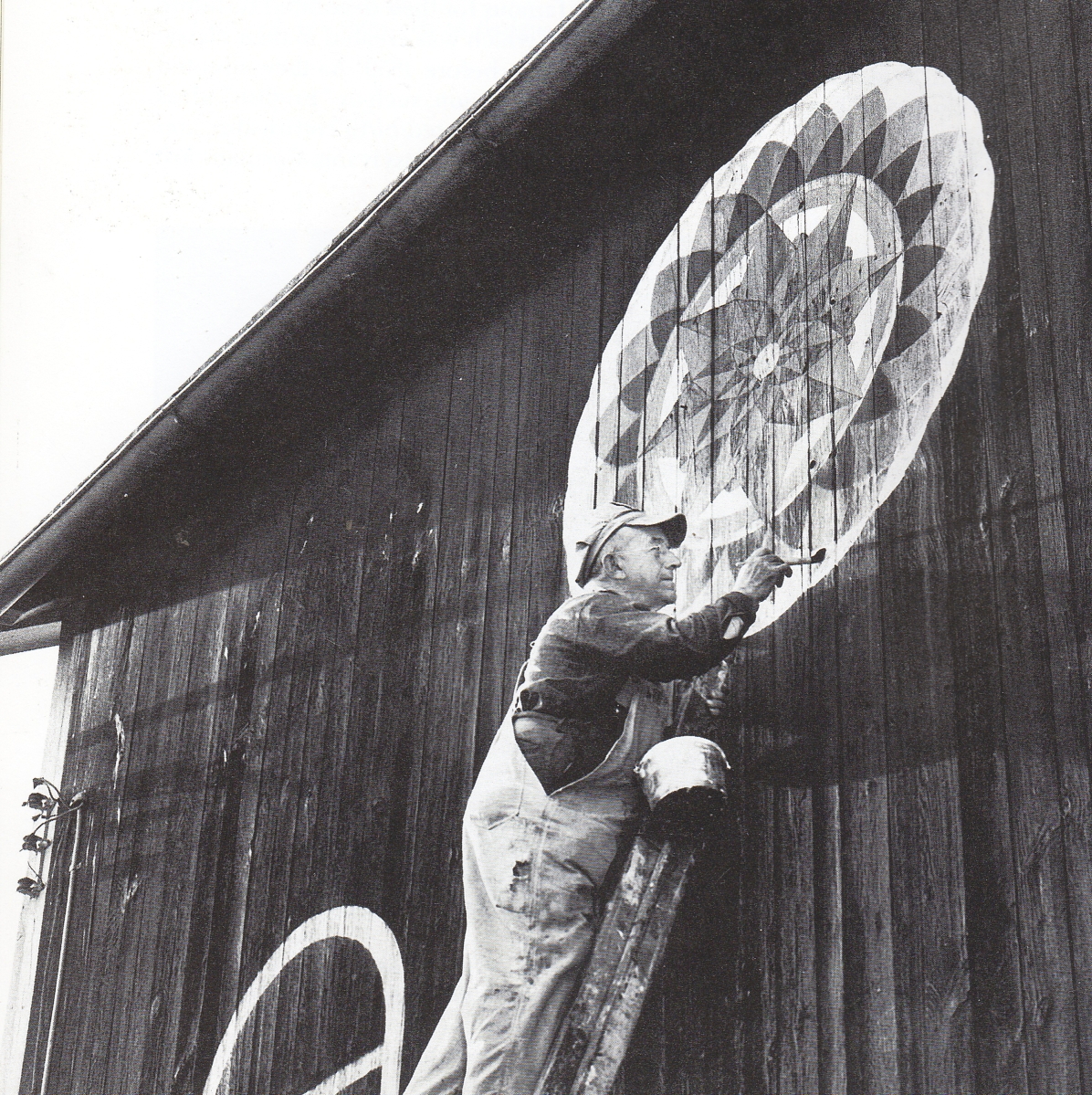

Milton Hill (1887-1972) was a third-generation barn star painter. He identified as a painter first, and as a barn star painter second. His father and grandfather were career painters of houses, barns and utilitarian objects. Milton followed in their footsteps. He’d get a job at a house, do the interior, exterior, perhaps even grain paint the cabinets, do stenciling. When he recalled his first barn star, he said he was asked to climb up on a ladder and repaint the stars on the barn of their home sometime around 1900. The barn was from the mid-Nineteenth Century, but the farm property had been in the family since the 1750s. Presumably, the stars on the Hill Family barn had been done by his father or grandfather before him. His engagement with the tradition was direct, and it was a seamless transmission passed between his grandfather, father and him. That’s one of the best circumstances you can have when learning a folk tradition – an uninterrupted passing from one generation to the next.

Was his grandfather the first-generation immigrant?

The earliest immigrant Hill ancestors arrived sometime between 1720 and 1727, and Milton Hill was of the seventh generation on American soil. His immigrant roots were very important to him, and his family helped found the early churches in the area and settled local farms. That’s a point of pride for Pennsylvania Dutch people, that their ancestors were a part of the transformation and establishment of the region’s communities.

Did he have a unique style to his barn stars?

Up until the time of Milton Hill, most local barn painters were creating stars that were formulaic patterns. We mostly see the same designs repeated often within given regions, especially 8-pointed and 12-pointed stars with tiny rosettes between each point, and braided borders around the earliest stars in the area of Northern Berks County. Originally, barn painters didn’t sign their work. As a result, we don’t know who the first painters were, or why they chose to express themselves in this way. In the late Nineteenth Century, there are a number of painters that have been documented, but not always with specific examples on local barns. In the case of Milton Hill, he was able to garner enough attention to have a clearly established corpus of works. At the Heritage Center at Kutztown University, we have his first watercolor paintings done in 1899 when he was in 6th grade. These early works differed from his later signature patterns, but still show a level of sophistication that was unparalleled in his time. By 1910, he standardized the classic Hill Star design. It was an 8-pointed star with a multi-layered starburst at center, and an interlaced border of multiple arcs. It was sometimes striped to highlight a gradient effect and he did it in a number of colors, sometimes up to ten. It became his classic signature design that he did on barns from the first decade of the Twentieth Century up until the 1950s when he retired and turned to painting on signboard, which he did up until the last few years of his life. Today, artists continue to honor Milton’s work by painting the Hill Star pattern on local barns.

Painter of the Stars, The Life and Work of Milton J. Hill (1887-1972) is available at www.masthof.com.

How would you describe Milton Hill?

Milton Hill was an innovator – usually folk artists are judged based on the way in which they adhere to traditional modalities. We expect a folk artist to follow suit with previous generations of artists and perhaps only occasionally develop new things, but usually in keeping within this narrow corridor of tradition. Milton stepped outside of that. He was able to develop unique, bold designs which served to expand upon the range of traditional patterns found in the region. He also is credited with having been the first artist to execute traditional barn star patterns on commercial signboard sometime around 1950, which was yet another innovation.

Are barn stars like quilting patterns? Do they get reused? Do certain patterns appear commonly in certain regions?

There are some similarities to quilt patterns, but also notable differences. Quilt patterns usually have succinct names and narratives associated with them, while barn stars do not generally. Barn stars vary considerably across Southeastern Pennsylvania. In these little pockets of rolling hills, you see some commonalities based on the range of individual artists. South of the Blue Mountain, you’ll see not only pieces by Milton Hill, but those artists whom he influenced. In Lehigh, the barn stars are more of a floral nature, lobed patterns that are variations of 6-pointed rosettes, incorporating rain drop or tear drop patterns that end up looking like floral bursts. Noah Weiss, who operated in the Lehigh Area in the later decades of the Nineteenth Century, favored these floral bursts, and you see echoes of his work throughout the Lehigh Valley. When we look at the impact of these individual artists, they create these spheres of influence. Because these designs are public, they can be copied by another artist directly. The artist drives by, says they really like it, snaps a picture of it. Quilts are in the home, they’re more intimate, created by groups of people and are less visible in the public sphere.

Did the designs mean anything to Hill?

There are words to describe the stars, but the stars often defy classification. The artist will know the difference between 8- and 12-pointed stars, but there’s only loose oral tradition around these designs. If you asked Hill, he said he was a “painter of various star patterns,” it said so on his business card. He didn’t like the term symbols, he would say it was “geometric,” or “just for nice.” He was a proponent that these were decorative and we weren’t meant to over-explain them. Sometimes people see the complexity and they expect the meaning to be elaborate. Meaning occurs on different levels, starting with the views of the artist. And then the appreciators, who respond to visual elements that play with the eye, and tend to assign ideas of mysticism or magic. Those aren’t consistent with what the artist would say, but I can’t fault the people for saying them. Barn stars echo the culture’s fascination with the heavens, regarding the stars as beacons of cosmic order.

What did Hill say about that?

Milton Hill would use the phrase “just for nice,” and usually with a thick Pennsylvania Dutch accent. The idea was that the barn stars were nice to look at, something to be valued for their artistic qualities, judged for their formal qualities, such as the artist’s ability to execute something visually complex and well-crafted, something where the geometry was very precise – and Hill was incredibly precise. When you look at his work later in life, post-1955, when he retired from painting on barns and only painted on sign board, his work got incredibly complex. They were dazzling to look at. He was a speaker of the Pennsylvania Dutch language. “Schtanne” was the word he used for his designs in the native language. When people asked what they meant, he told them they were stars – which was about as descriptive as he got. But that dialect terminology was important to him, these were the true vernacular forms of his work.

About when did supernatural ideas come into play about barn stars?

The idea of supernatural associations began in the early Twentieth Century due to the misleading influence of travel journalism from outsiders who coined the idea of the “hex sign.” But for the Pennsylvania Dutch, these designs appear on tombstones, decorative datestone inscriptions, birth and baptismal certificates. They especially appear on items meant to be valued, types of objects that have dates and names associated with them. There’s a whole realm of polite and very whimsical types of designs that are used, but the presence of stars in connection with texts is very important. They indicate to us that people that are considering the passage of time and the ephemeral nature of life, and they will oftentimes depict stars as the reference to time and the passage of time in the sacred sense. I wrote a book called Hex Signs: Myth and Meaning in Pennsylvania Dutch Barn Stars that explored this idea of celestial symbolism.

Folks from outside of the culture really had no idea how to interpret these, which is why they usually turn to the flashiest ideas that could be found. Supernatural stories of witchcraft, this still goes on today. There were a handful of authors who promoted the supernatural ideas, like Wallace Nutting as a travel writer. But he was really a retired congregational minister and armchair historian – a person who didn’t have formal training as a historian. We see an influence of these gentleman historians who believed they were uniquely positioned to interpret aspects of culture, and unfortunately they left us with many misconceptions.

There was another artist, Johnny Ott, who promoted supernatural meanings of hex signs painted on commercial signboard. He was somewhat of an outlier, a Roman Catholic Pennsylvania Dutch painter who dressed as an Amish person. He was born in 1880 and died in 1964. He was the one who was almost single-handedly responsible for promoting, from the artist perspective, the showmanship and the marketing that allied with the tourist narrative of the hex sign. Hill had strong opinions of Johnny Ott and he did not appreciate what he saw as misleading marketing. Hill was a third-generation painter and Ott never painted on barns. I’m happy we have Milton Hill’s narrative that contrasts with Ott’s, as we had the benefit of Hill’s extended cultural memory from his father and grandfather’s generations.

How common was barn star painting as a profession during Milton’s life?

It’s tough to say, we mentioned Weiss, Perry Ludwig from no more than ten miles away in Centerport, Harry Adams who was working in the 1960s through the 1980s, and he learned from Milton Hill. Then there are a wide range of other people, Donald Smith, who painted from the 1970s through the 1990s, he was in the same community and went to the same church as Milton Hill. There were also farmers that painted their own barns. Every area had their own painters, just like Milton Hill, that painted in Virginville and the surrounding townships. There was a painter in the Palm area, northern Perkiomen, and near Huffs Church, Elton Ruppert. He painted all throughout the area immediately surrounding his farm.

When did barn stars make their debut in the US?

In 2008, I had gotten a grant to do research documenting the decorated barns of Berks County, and the surrounding areas. There are some in Berks County that date to 1805, one not far from Virginville is 1819. There’s a neighboring farm to Milton Hill that had a star from 1810. The earliest I’ve found is from 1786 and it’s on a barn way down a back country road, it’s not public, but it’s on the border region between Berks and Montgomery counties. And not far from there is another star on a house from the 1780s. So we know the earliest examples are from this tri-county region between Berks, Montgomery and Lehigh, and the interesting thing about that corridor is the location of the King’s Highway, a throughway established in the early Colonial Period. This is the corridor of distribution of the barn stars, and the earliest examples all fall within ten miles of that corridor of King’s Highway. These earliest examples are not just found on barns, some on houses and mills, these are in keeping with some formal decorative elements that we would find on Georgian architecture.

Did barn stars evolve?

We find ornate circular medallions with trim, borders and keystones on formal examples of Georgian and Federal architecture. This blossomed in the Federal period, following the revolution. This is part of that story, as architecture developed in this area, and formal elements became vernacular by the first couple decades of the Nineteenth Century. Medallions on houses and barns incorporated dates and names – and they were formal aspects of dedication – but by around 1840 the names and dates have moved to the front of the barns. They became centerpieces, filled in with not just one star but with multiples, and then you have articulations along windows and door hangings. It became part of a complex and comprehensive way of decorating the barn. An architectural transition took place – barns were once stone all the way up to the gable peak, and by 1840s, most upper gables in the region were frame. Instead of the upper gable, artists painted the names and dates on the front of the barn in a much larger, formal way – they wanted people to see them.

A classic Milton Hill Star, painted on commercial Masonite signboard sometime in the late 1950s or early 1960s. This technical development in painting surface revolutionized the art of Pennsylvania’s barn stars, allowing the stars to be applied to any type of building and at any location throughout the world. Courtesy of Phares W. & Mabel M. (Heffner) Fry (granddaughter of Milton & Gertrude Hill) & Family.

What was business like as a barn star painter? Was it lucrative?

Milton Hill’s wife Gertrude paid more in taxes and made more money annually than he did running their dairy farm. He probably worked six days a week and long hours, and his wife did too, but she also raised the children and kept the home. According to Hill’s ledger from the 1920s, he paid himself 15 cents per hour and the people who worked for him were paid 10 cents. For the painting of an entire house and barn with barns stars, he gets paid for a total of 206 hours and his partner, 205¾ hours, and they make $30.90 and $20.57 respectively. This combined total is around $1,300 today. If you look at the rates of pay, the hourly rates, adjusted for inflation, 10 cents an hour is $2.27 today and 15 cents is $4.09 today. It wasn’t lucrative work. When he was painting, his wife was holding down the farm, raising the kids and she was the breadwinner. Through this, we can see how he was able to deliver this body of work in his community and be so prolific – it was at least partially facilitated by the hard work of his wife.

Lee Heffner wrote a concise autobiography of Milton Hill, what are some of his most notable life moments?

My coauthor, Lee Heffner, is Hill’s grandson. Much of the biographical side come from Lee’s memories and interviews with his family. I feel these stories really fill out Milton’s character and help people understand him as an artist. He had aspired to be an inventor and engineer, he was a person who pushed people’s expectations of a rural artist. He was fascinated with research on perpetual motion. He made prototypes of a perpetual motion machine that he kept in a shed. In his spare time, he was experimenting with physics. He had also built a mousetrap that parallels his interest with perpetual motion. In order to get the bait, the mouse pushed against a series of doors that set a spring-loaded trap that would kill it.

Is it a living tradition today?

Milton taught his oldest son, John L. Hill, however, John Hill passed away in a car accident in 1963. He was not only a painter of barn stars, but he would also do murals of livestock scenes on barns. These are similar to the WPA, when we see a huge interest in murals in the earliest Twentieth Century following the Great Depression. Milton would say John was the artist in the family and his death severed that family tradition. Milton’s real impact for the next generation was his influence on other painters. Harry Adam worked long after Hill passed away, a local painter in the same area as Hill. Then there’s the Claypooles, Johnny Claypoole, a World War II veteran. He was born in 1921 and passed in 2004. His son, Eric, who was born in 1960, is the most prolific painter in the present day. He has painted nearly 100 barns and he’s painting half a dozen barns a year. Johnny Claypoole learned to paint from Johnny Ott. Johnny Ott never painted on a barn, just commercial surfaces. He taught Claypoole to paint in 1962, two years before he died. Claypoole was a go-getter, he did all kinds of architectural work. He probably painted several dozen barns, but his son Eric made a career out of it. I learned to paint barn stars from Eric Claypoole and I’ve done a number of barns. My colleague Andrew Shirk is an apprentice of Claypoole. We like to think of tradition as being passed in ideal scenarios like Milton Hill learning from his father, who learned from his father before him, but we also find these traditions tend to jump around, and they get invented and reinvented by subsequent generations who keep the tradition alive, and continue to find meaning and inspiration in the art.

-Greg Smith