In a love affair with New York City’s subway system, Philip Coppola, or Copp as he was known until August 2021, for the past 40 years has been painstakingly hand-drawing details from each and every station he has recorded so far. In his 70s, he says he won’t stop until the whole thing is documented. Antiques and The Arts Weekly followed Coppola down into the depths of his impassioned project to get some insight into this American subterranean artform.

Why did your surname change in August 2021?

I restored my last name to my father’s original family name when I was 73 years old. Why? Because my father altered his last name a century before, and I had to grow up with his abbreviation, but the name or the word “Copp” is, in my opinion, rude, brief and not euphonic. Coppola is more honestly the ethnic original from which I come.

Brief biography?

I was born in New Jersey on February 25, 1948. Grew up with a penchant for drawing pictures and telling/writing stories. Attended Rhode Island School of Design aiming for a degree in fine arts painting, but didn’t make the grade. Lived on the Lower East Side while holding down an office job, then moved to Sunset Park. Quit the office job, gravitated to Provincetown, washing dishes. Hitchhiked a bit; to Maine in ’72, to New Orleans for Mardi Gras in 1973. Returned to New Jersey and found my trade in the printing industry, running letterpress machines. Did that until 2021. Now working at a Staples store.

Where did the idea for documenting subway stations come from?

The idea for looking at the subway stations came from my father. When I was about eight years old, he told me that down in the subway stations in New York City there were tile pictures on some of their walls showing buildings and scenes of New York City in the 1800s. That intrigued me. What was he talking about? What did they look like? What scenes/buildings do they show down there underground? I kept this idea in the back of my mind for about two decades, and then decided, in my late 20s, to go and see for myself what my father was talking about.

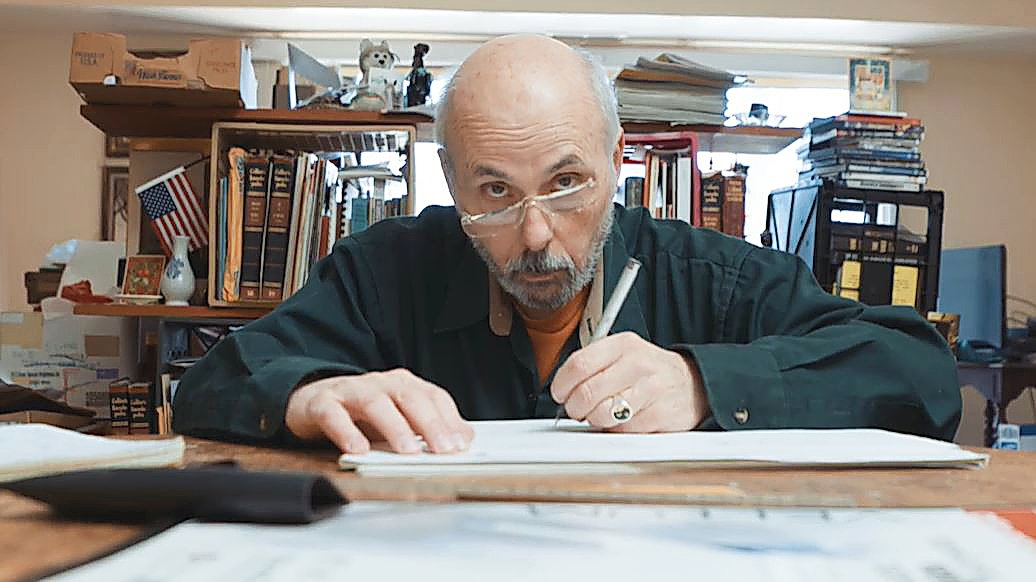

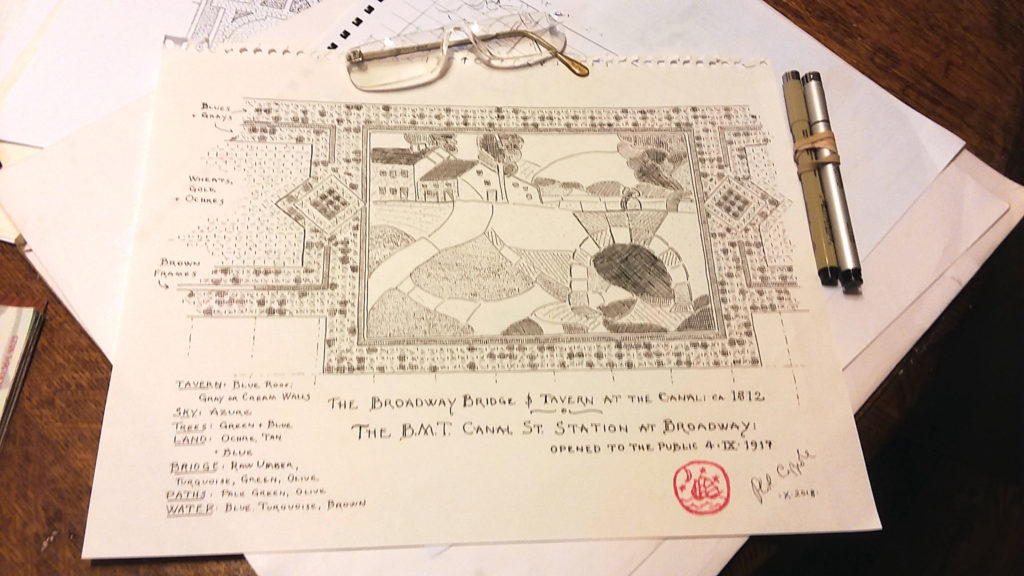

A Phil Coppola drawing in progress on a table. “This is my drawing of the BMT’s Canal Street plaque, from the 1918-20 Broadway line in Manhattan,” said Coppola. “These plaques are seen now on the station’s entrance mezzanine and used to adorn the side walls of the Broadway station, as well as the lower-level station.”

What was your initial goal and how did it morph into something larger?

My initial goal for this project was to go see a bunch of stations, draw some nice pictures of the art embellished there, write the stories of what those pictures mean and sell an article to a magazine in a few months. My project snowballed into a larger endeavor because I intended, as a matter of respect for those who had created all this, to give credit where it was due. So I needed to know the architects’ names — or the artists — and I could not readily find such information. No one I asked seemed to know. So I began digging here and there, and came up with several names of people who intrigued me, and I wanted to know more about them — Parsons, McDonald, Belmont, Orr — and so I gathered material about them. Were they the ones who created the subway art? No, and I finally found the architects’ names — Heins & LaFarge — and I investigated them. Also, as I discovered as I went along, the stations are many and varied, and the earliest ones — which are the ones I cut my teeth on — have the most lush Beaux Arts features to explore and draw. Glad I did them first when I was younger.

What year did you start?

I began experimentally in the summer of 1977. I knew nothing of the subway system, except that it was foreign to my experience, but I at least knew the West 4th Street Greenwich Village hub station. So I started there. But it is an IND station — no pictures there. I stuck to my guns and the system’s lines I was recording, and covered all the IND stations in Manhattan. The next summer, on July 1, 1978, I officially began my research, deciding to get a handle on the subway’s history and begin at the beginning.

How many volumes have you completed to date?

I have completed four big volumes so far, covering the IRTs earlier lines in Manhattan, the Bronx and Brooklyn, wrote up a history of Brooklyn’s Rapid Transit Company lines and also covered the PATH trains — formerly the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad. Though PATH is not corporately a New York City subway, it does run into Manhattan. So it’s part of the Manhattan underground scene. And then more recently, I have produced two slim “portfolios” — the IRT Pelham Bay line in the Bronx and the IRT Lexington Avenue line in Manhattan.

By the way, for those who don’t know what the IRT is, the IRT today is the numbered trains — 1 through 7. I am currently working on two more portfolios; the BMT Sea Beach line in Brooklyn and the IND in Manhattan. Again, for those who don’t know what the BMT or IND are: the BMT is the trains J through Z, and the IND is the trains A through G.

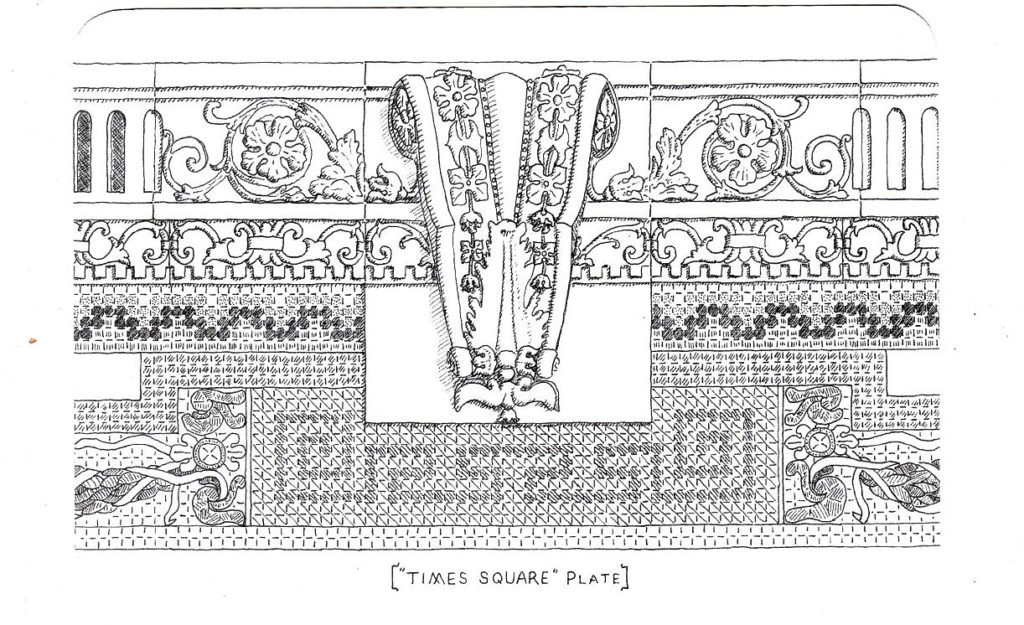

“Times Square plate” illustrating the invitation/announcement to Coppola’s Grand Central MTA shop and gallery show in 2018. This drawing shows the faience cornice and console of the sprawling Times Square name panel.

Why are you doing it?

I am making this record of the subway stations’ interior embellishments, not just to make a record of what we have, but also to reclaim what we’ve lost before much more time has passed. When I undertook this project in the 1970s, the mosaic patterns lavished on some of the stations — essentially those on the BMT’s 4th Contract lines (Broadway/Manhattan and 4th Avenue/Brooklyn) had been buried behind nonentity big block walls. Philip Johnson had redone the IND’s 5th Avenue and 53rd Street Station, and, most urgently, when I came upon the scene, the unique art mosaic patterns of the 1905 Bowling Green station had just been buried behind walls of glazed red brick, and the IRT’s 1917 Cortlandt Street Station was being denuded of its mosaic band and its hexagonal ferry boat plaques to be repaved with glazed beige bricks. Someone had to record these lost examples of civic art, and that would be me.

So, you’d characterize this as civic art?

The several eras of embellishment clothing the New York City subway station walls is civic art; from the Beaux Arts “City Beautiful” early IRT stations (1900-1908), to the Arts and Crafts mosaics and plaques of the Dual Contracts stations (1914-1920), to the Machine Age IND stations (1932-early 1940s or so). Now we’ve got Space Age stainless steel and some mosaics, plus other media stations.

Someone remarked that you could just take pictures of the art. Why recreate it onsite?

I am drawing the decor because black and white drawings cost less to produce than color photos. And my altruistic aim was to produce books accessible to the general public with a low price per book. But my three rabbis — long explanation — have induced me in this century to charge a price per book commensurate to the labors I go through to produce them; stop giving them away at ridiculous asking prices, they told me. I have listened.

How many stations have you documented to date and how many are left to do?

I have counted the stations of the New York City system at a total of 496 stations. Up through four volumes and two portfolios, I have covered only 121 stations, leaving 375 (my count) left to go.

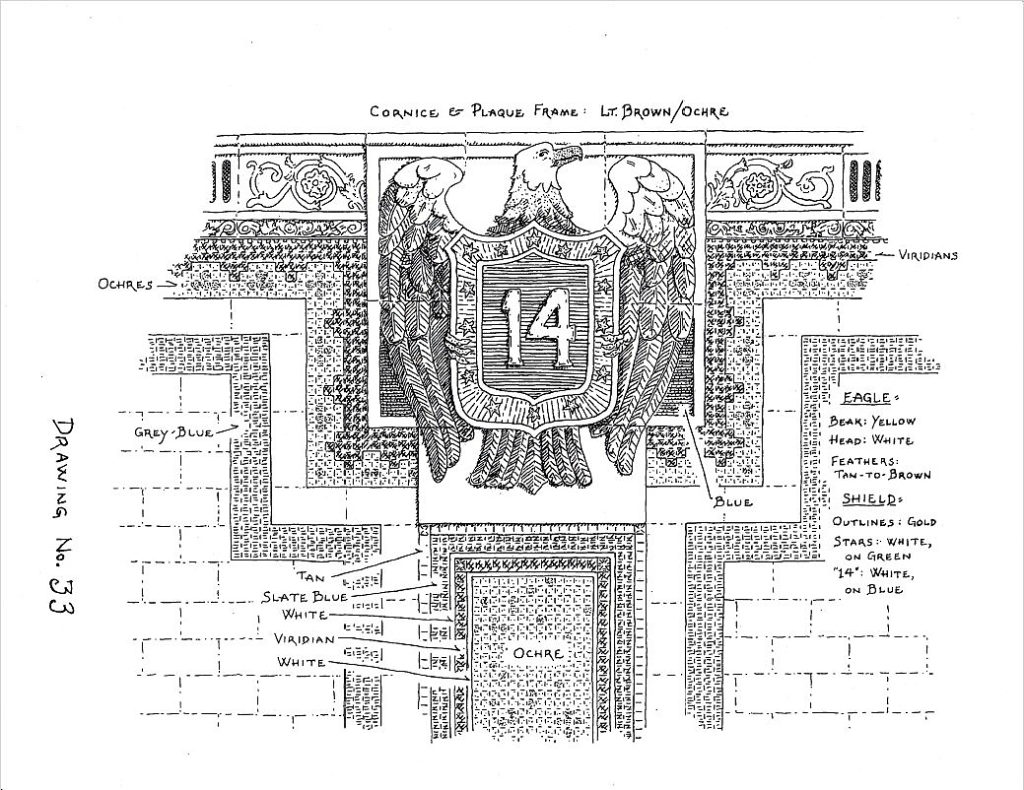

The eagle and escutcheon plaque fabricated for the IRT’s Contract 1 1904 station at Union Square/14th Street. These plaques had been hidden from view since the early 1900s and were restored to the public’s sight through a construction job reconfiguring that old station. This is one of three sets of eagle plaques worked up for the IRT’s Contract 1 line.

Is your project recognized and supported by the MTA?

The MTA/TA is aware of my project. Over the years since 1984 they have received copies of my books as they have become available. My efforts are not supported or augmented or financed by either the MTA, the TA or any other agency or foundation. I am independent and private.

Is there a station whose art proved to be your favorite?

The Borough Hall Station in Brooklyn has to be the very epitome of LaFarge’s genius. It has all the majesty of a Roman banquet hall, with a gorgeous panel and bronze plates at the entrance, two varieties of mosaic pilasters downstairs, an enormous name panel replete with festoons and ribbands and Greek frets and fleurettes, a faience cornice of egg and acanthus leaves, with a bead and reel border. And a stately faience bas-relief “BH” monogram set on a fluted plate surrounded by a laurel wreath. These surmount about half of the number of pilasters in the station. They can’t be beat.

— W.A. Demers

[Editor’s note: Anyone interested in contacting Phil regarding book sales, email him at pac4op@earthlink.net.]