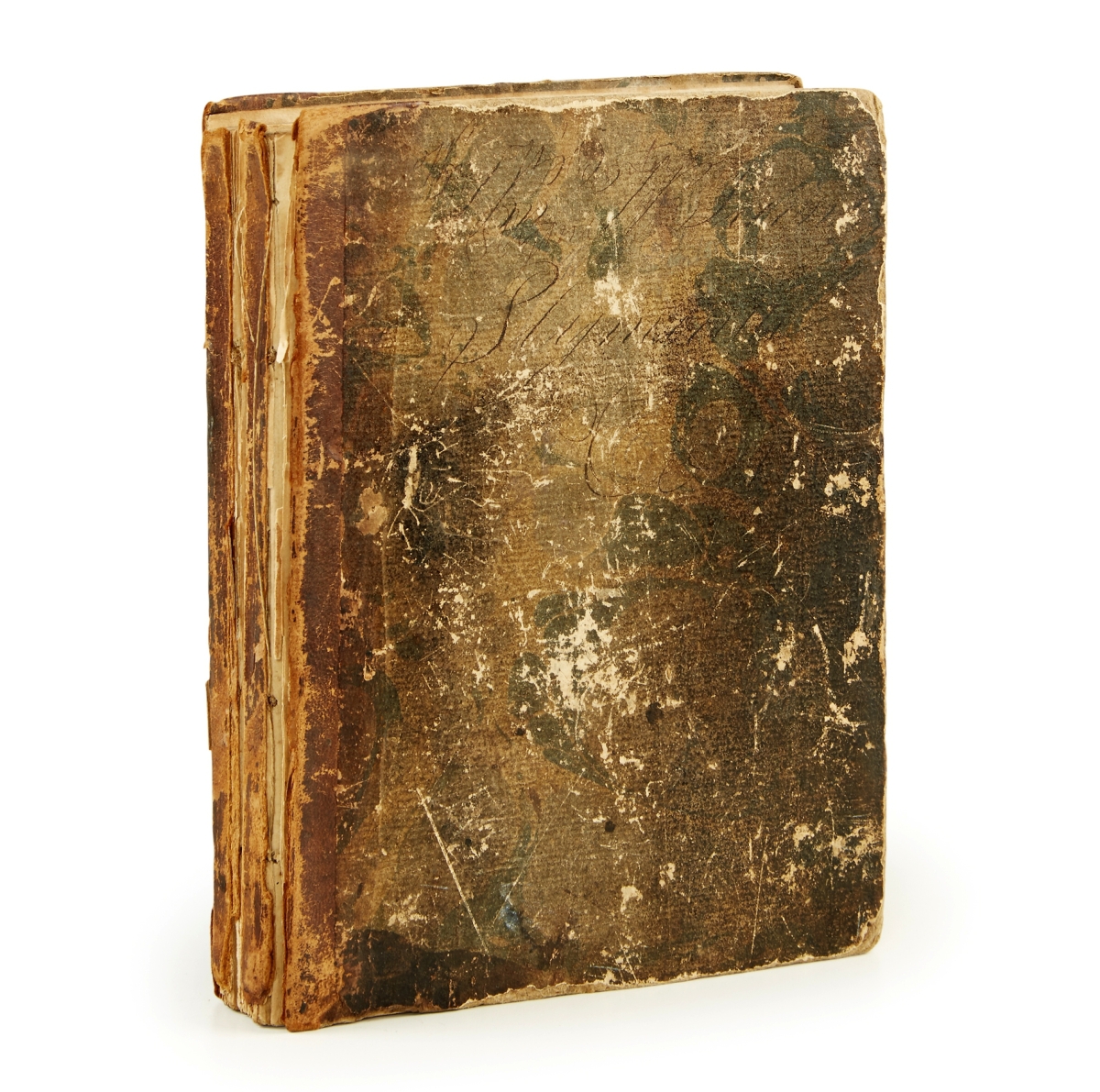

A sleeper at Freeman’s January 30 Books, Maps & Manuscripts sale was a nearly 300-page quarto-volume cataloged as [Americana] [Connecticut Clockmaking] and described as an “Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century Manuscript Business Account Book relating to Clock Manufacture in Connecticut;” the catalog entry further said it bore the ownership signature of Plymouth, Conn., clockmaker, Silas Hoadley. Antiques & The Arts Weekly was tipped off that the book was acquired by Philip Morris Jr on behalf of the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors (NAWCC). Morris is a horology scholar and is not only on the board of directors for the NAWCC but is also the chairman of its collections committee. In 2011, he wrote American Wooden Movement Tall Clocks, 1712-1835 and seemed the most likely person to understand the importance of the book. This seemed to have the makings of a great discovery story, so we reached out to Morris for his insight on what made this book so special and what plans the NAWCC had for it. As it turns out, it was a book of revelations not even he was expecting…

You were bidding on Silas Hoadley’s 1814-1853 account book. For readers who don’t know who Hoadley is, why is he important and why was the NAWCC so interested in acquiring the volume?

I think that to best understand Hoadley we first have to look at one of Connecticut’s most famous clockmakers, Eli Terry, since Hoadley’s earliest clockmaking experience came from working in Eli Terry’s “Ireland factory.” The transition from handcrafting to mass production occurred in Plymouth, Conn., under the direction of Eli Terry at this factory and as a result he would soon become America’s most famous clockmaker. Terry developed methods for producing interchangeable parts using water-powered machinery. This system allowed Terry to produce large numbers of identical parts that required minimal hand finishing or adjustment. Terry experimented with interchangeable parts from 1800 to 1805 but he did not implement his ideas on a large scale until two years later. In 1807, Terry secured a contract and funding from Rev Edward and Levi Porter for production of 4,000 wooden tall clocks to be delivered over a three-year period (this is known as the “Porter Contract”). An early Waterbury, Conn., town history records the two men were brothers but in fact they were not related to one another apart from their business association.

Terry, with the help of Hoadley and Thomas, successfully completed the Porter contract in 1809 and his manufacturing techniques were widely copied by other makers. The realization of Terry’s ideas revolutionized the American clock industry and for the first time made affordable clocks widely available to the public.

Hoadley was one of the most famous and prolific Nineteenth Century clockmakers from Connecticut and his clockmaking career spanned 1807-1850s. He apprenticed to his uncle, who worked as a joiner and carpenter and a significant part of career was spent producing 30-hour wooden movement tall clocks. As mentioned above, he started his clockmaking career in 1807, when he helped Terry manufacture the Porter Contract clocks. In 1810, Hoadley and Seth Thomas (who later also became a very famous clockmaker) purchased Terry’s Ireland factory and began manufacturing clocks as Thomas & Hoadley. They dissolved their partnership in 1813 and after this time, Hoadley began working independently.

The account book is interesting as the earliest Hoadley entries are for 1814 corresponding to the first year he worked alone.

Were you aware of the book before it came up for sale?

I was not aware that this account book existed prior to the sale. In fact, I am not aware that anyone in the clock field knew of it. Fortunately, about three weeks prior to the sale, the NAWCC was made aware of the book and separately I was contacted by a number of collectors who knew of my interest in Hoadley and other early Connecticut clockmakers.

Did you have any expectations or hopes of what the book might reveal?

Before the book arrived, I was interested if the account book gave some idea of the production numbers for Hoadley and if the dates could help us sort out when he stopped production of some clocks and began others. Of interest also was who Hoadley had business dealings with.

What did you find when you started looking through the book?

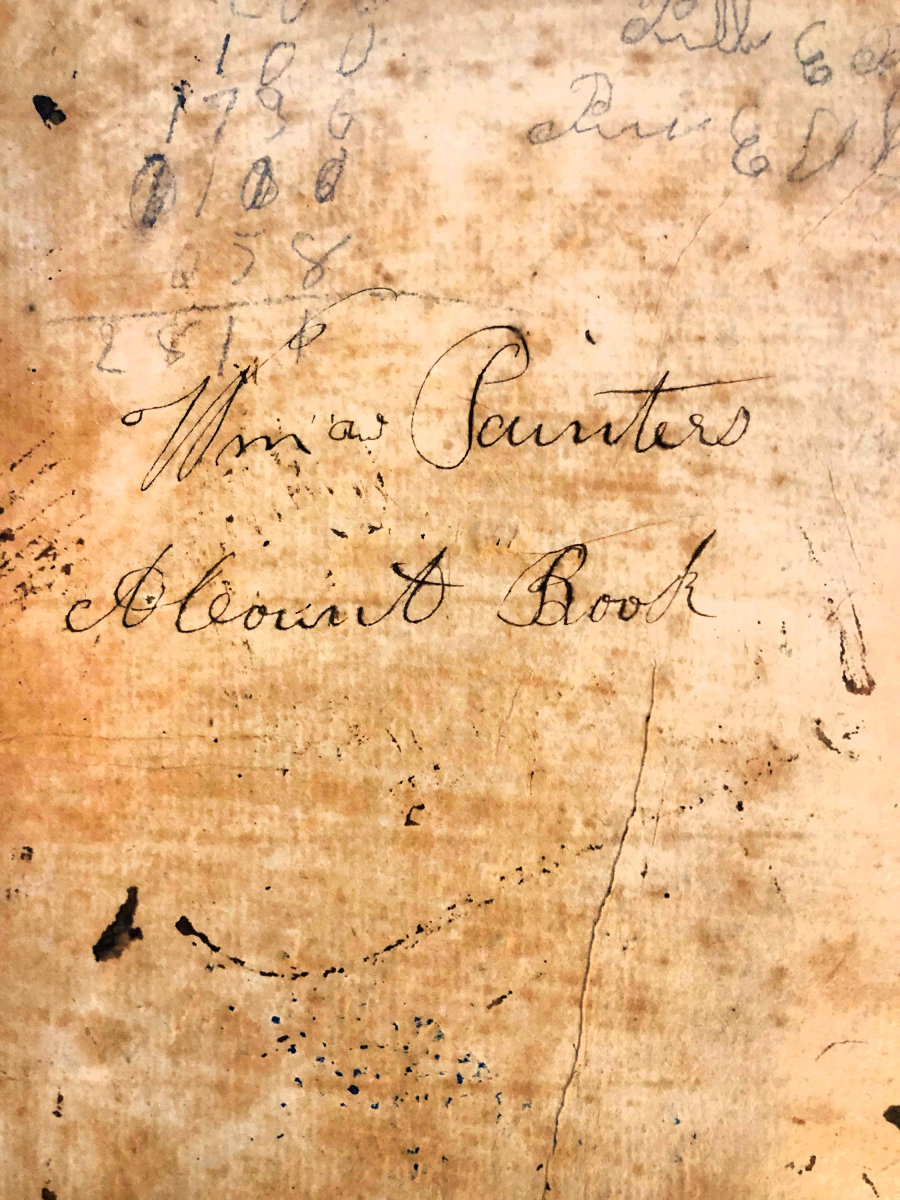

When I received the account book, it quickly became apparent to me that this was not Hoadley’s account book as all of the entries were related to dial painting and I could find none related to clocks. While it is true that the account books inside front cover is inscribed two times in pencil with a signature that looks like Hoadley, it is my opinion that this was added much later. Indeed, the front cover also contains a very faint cursive signature of William Painter. When I began to look carefully, I noticed that there was an account book page stuck to the inside back cover. I carefully removed it and there was a very nice signature that identifies the account book as that of William Painter. I was actually very happy to discover this. My excitement grew as I studied the account book further as it is now apparent that he was a major supplier of painted dials to many of the most famous Connecticut clockmakers. For the first time, we are able to attribute some of the dials to a specific shop.

Did you know who William Painter was?

While the surname Painter was well known to me, I did not know who William Painter was and was unaware of his important connection to the Connecticut clock industry.

How does William Painter connect with Silas Hoadley?

Hoadley married a woman by the name of Sarah Painter and it turns out that William was her brother. William’s connection to Connecticut clock industry goes even further as his sister Chloe was married to the clockmaker Ephraim Downs, and his sister Lucina was married to clockmaker Butler Dunbar. Clearly Painter was well connected to the local clockmaking industry through his sisters.

What is his contribution to the larger world of Nineteenth Century clock-making?

In my book, American Wooden Movement Tall Clocks: 1712-1835 I identified more than 600 clockmakers, factory employees, cabinetmakers, dial painters, suppliers and peddlers that supplied the wooden clock industry in New England. Surprisingly, Painter was not one of the dial painters I had identified. Painter’s importance is that he supplied thousands of painted dials to some of Connecticut’s most famous clockmakers, including Eli Terry, Silas Hoadley, Seth Thomas, Norris North of Torrington, Asa Hopkins and his nephew Orange Hopkins of Litchfield. He is the only dial painter that we can attribute this many dials to.

You’ve had the book for just a couple of weeks…has the book divulged more revelations?

In addition to listing his dial customers, the book also gives us a good idea of how many dials Painter was delivering with each order which was somewhere around 100. It also gives us a good idea of the number of dials he painted over a certain time period. For example, the book records that he painted a total of 1,562 dials for Silas Hoadley between May 1816 and September 1816. Like many period account books, this one records many other transactions other than dial painting.

Signature of William Painter stating

“William Painters Account Book,” inside back cover, Philip Morris, Jr photo.

You wrote the book on American Wooden Movement tall clocks…what does this book stand to do for your research? That of the field?

For the first time, we can now attribute some painted wooden dials to a specific dial painter and shop. Interestingly, the account book also expands our notion of dial painters as it is generally accepted that these dials were painted by women and young girls. One such female dial painter who is well known is Candace Roberts, who was the daughter of Bristol, Conn., clockmaker Gideon Roberts. She recorded that she painted dials for some clockmakers in a diary that she kept, but the information is very sparse and gives little other information in contrast to this account book. Of course, it may well be that Painter had women working for him painting dials but that is not something that can be confirmed at this point. In addition, Painter’s account book provides a great deal of new information on the vernacular of his trade. For example, all dials are called “faces” in his account book. The account book does a very good job of describing the different types of dials that Painter supplied. For example, “painting one hundred & seven Clock faces” in an April 1819 entry for Hoadley referred to painted wooden dials used for Hoadley’s 30-hour wooden movement tall clocks. In September 1819, an entry “painting one hundred and fifty three Eight day Clock faces” refers to the wooden dials used for his eight-day wooden movement clocks.

The account book also tells us that Painter charged $0.05 for each dial and that the price was the same for both the 30-hour and his eight-day dials. This was a little surprising to me as his eight-day dials are typically more heavily decorated with gilt than his 30-hour dials.

In a June 1814 entry, Painter recorded “painting five thirteen-inch faces” for Silas Hoadley. This entry refers to a small number of oversized painted wooden dials that are found today and that are typically housed in cases made by Lexington, KY., cabinetmaker Elijah Warner. These dials are rare today and the account book shows that he painted very few of these which is in good agreement with the few that are known today. These dials required additional decorations compared to the standard 12-inch dials (a standard dial measures 12 by 16 inches) and Painter charged $0.08 for each of these.

He apparently painted and delivered dials to Litchfield clockmakers Asa and Orange Hopkins and the cost was $0.065 for these, with the extra penny and a half charged per dial for delivery.

Other entries describe “boaring” faces, which is a description for drilling or boring a hole in the dial for the center arbor to pass through as well as “priming” and “varnishing” faces.

In 1821, the first entry among several for Eli Terry appear for “painting 124 patent faces” which are for Terry’s patented pillar and scroll shelf clocks. These dials are about 12 by 12 inches and Painter charged Terry $0.05 per dial. On a single page, the account book records that Painter provided Terry with about 2,000 of these dials.

13-inch Silas Hoadley dial for Elijah Warner clock case,

Philip Morris, Jr photo, courtesy Philip Morris, Jr.

The NAWCC library has about 50 other account books. Are they accessible to researchers? Will this one be as well? Is this book unusual in any way from any of the other account books? How so?

The NAWCC (in Columbia, Penn.) has the largest horological library in the United States and it is accessible to both our members and the general public. Non-members would have access to our library as part of the museum admission fee, and our members, of course, are free to use the library or visit our museum anytime they want. All of our account books and other primary research materials are available for study, and it is suggested that an appointment be made in advance to look at these. This account book is the earliest account book in our collection and is the only one associated with dial painting.

What’s next for this book?

The book is in overall very good condition but there are a few loose pages that will need to be repaired. The book will then be digitized, and these images will become available to interested researchers, collectors and historians. Arrangements can also be made to view and study the book in person through the NAWCC’s library. The book will also be loaned to Gary Sullivan, a well-known author, researcher and early American clock specialist. He is working with co-curator, Brandy Culp at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn., on a 2021 exhibition of significant Connecticut tall case clocks, some of which have dials that may have been painted by William Painter.

-Madelia Hickman Ring