Richard Reifsnyder.

Louis Bucceri.

The Salisbury Association in Salisbury, Conn., has recently completed a historic conservation project to restore and preserve an exhibition display of Nineteenth Century pocketknives from the Holley Manufacturing Company, which was based in Lakeville. We caught up with Richard Reifsnyder, trustee emeritus and former chair of the Historical Society, and Louis Bucceri, who is the Salisbury Association’s office manager and executive assistant, to discuss this project and its significance.

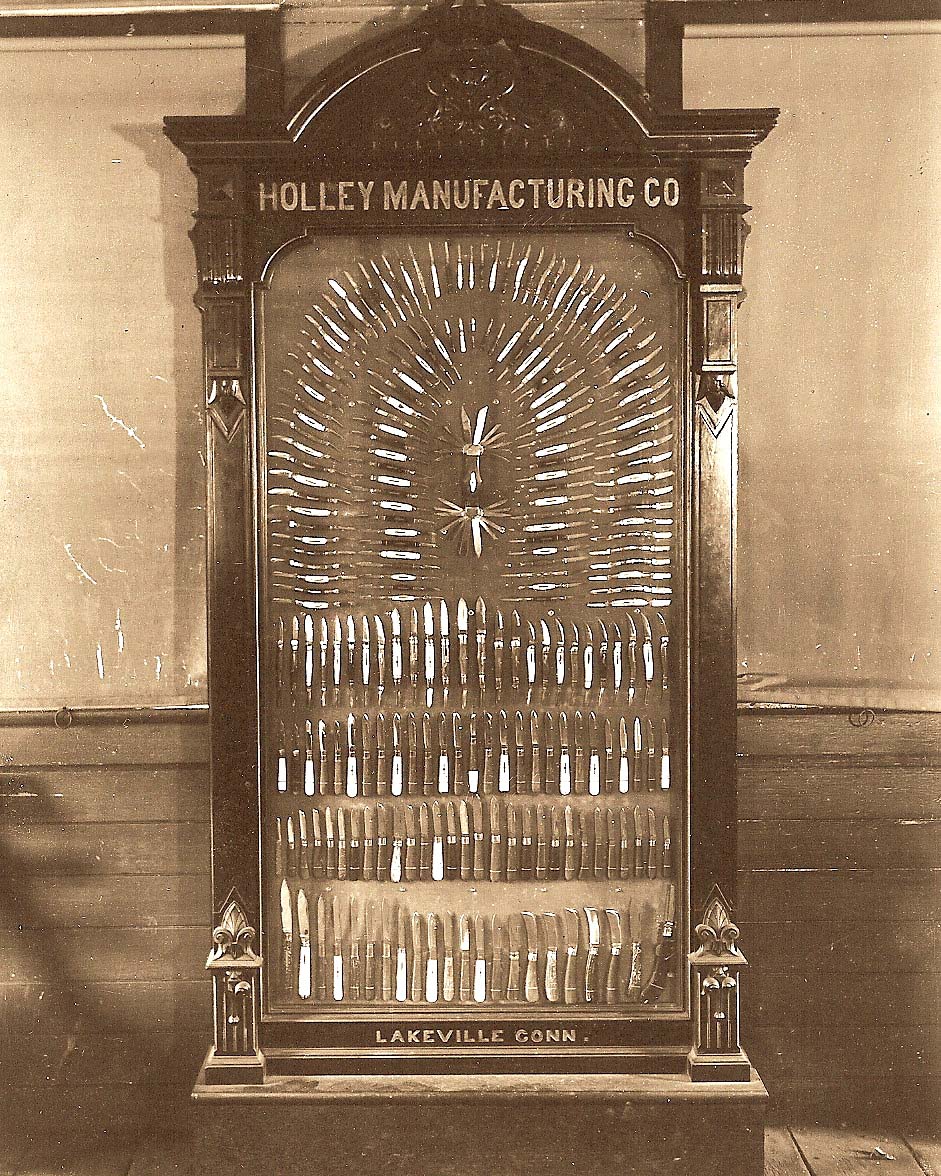

The Holley Manufacturing Company knives were shown at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. What was significant about this display? Can you tell us about the history of these knives and the display?

RR: In many ways, the knife collection is one of the key artifacts that the Salisbury Association possesses, and its significance is that the original knife collection, and the case that it’s currently in, were displayed in 1876 at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. And that exposition, of course, was intended to highlight America’s industrial development — its burgeoning role as a world power and economic power. And it’s just interesting, 30 years after the company was founded, Holley was there present at that exhibition, showing off its wares — 222 knives were displayed, showing a variety of the products that the company made. Again, making its mark on America’s burgeoning industrial history.

LB: The significance of this collection is that it shows a really important part of Salisbury’s industrial history. There were two other Salisbury entrants into the Centennial Exposition, both of major industrial imports. The Holley Manufacturing display was sort of put on a pedestal and still emphasizes the significance of that industry to our local area.

Guests at the opening reception for “The World Comes To Salisbury: Celebrating The Holley Knife Collection” at the Salisbury Association’s Academy Building. Courtesy of the Salisbury Association.

How did the exhibit end up at the Salisbury Association Historical Society?

RR: After it came back from the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibit, it was housed in the Holley Manufacturing Company buildings for many, many years. Then at a certain point in the 1940s, the company was kind of on the decline and was getting ready to go out of business, they were looking for a place for the knife exhibit. It first went to the Scoville Memorial Library on loan and then, eventually, the library took possession of it as a gift from the company. It was there for a number of years until the library eventually chose to give it to Fred Leubuscher, who became the owner of the Holley buildings [after the company was no longer in existence.] It was given back to him, and it was housed once again in the Holley building. He wanted to give it to the Salisbury Association when the Salisbury Association developed a museum. As Lou mentioned, the Association owned a historic house, the Holley-Williams House. So, when the Salisbury Association began to be housed in that building, Leubuscher gave the knife collection to the Association and it was there until the Holley-Williams House was sold. Then when it came back in 2010, it came to the Academy Building, which is where it has been housed ever since.

How did the conservation project come to fruition?

RR: About five or six years ago, a man who was a significant knife collector and had knowledge of knives came in and saw the exhibit and basically said to the Salisbury Association, “these knives are showing signs of deterioration on the handles. There’s tarnish on the blades and corrosion because of the way they’ve been mounted, and you need to think about doing some kind of conservation work if you’re going to preserve this exhibit in perpetuity.” And so that was really the precipitating sort of fact for us thinking about it.

How long did the entire project take? What were some of the key steps?

RR: It was about five years. Initially we had several conservators come in to give an assessment of what they thought needed to be done and what were the challenges of it. It took some time just to do that analysis there. Then finally we had to decide on getting the conservator to do it. We came upon Fallon & Wilkinson, whose specialty is actually in woodworking. We knew they could do a great job on the walnut cabinet, and they were confident in their experience that they could do the job necessary. We worked very closely with Fallon & Wilkinson and felt very fortunate Randy Wilkinson was excited about the project and the learning he would be doing when he undertook it.

We had to carefully pack up all the knives and dismantle the old exhibit, identify each of the knives to get them into a proper inventory, then had to do an evaluation of every single knife and what kind of conservation techniques would be necessary because they are all different kinds of handles and materials. That took the better part of a year before they could even begin the conservation. That took a fair amount of time and, in the middle of all that, we were trying to figure out how to raise the money for the project.

Then, working with designers we had a number of decisions to make — for example, the nature of the backing on which the knives would lay. The original was purple velvet, but we wanted it to live up to the current best practices for museum-quality exhibits. Of course, we found things they did not know back when the original was made. There are apparently all kinds of issues concerning how fabric and fabric dyes interact with metals, so it took us some time to work through that with what would be available and appropriate. There were just a lot of details and decisions which took us some months to make. This was a project we knew we would only do once every 50 years or so, so we wanted to be sure we did it as close to perfection as possible.

The 1876 Centennial display. Courtesy of the Salisbury Association.

How similar to the original Centennial Display is the “new” conserved exhibit piece? Why was the design changed?

RR: There were actually two incidents of vandalism. One took place in 1950 when the library was broken into. The glass covering on the knife exhibit was smashed and a number of knives were taken. After that, they did some redesign on the display itself when they put it back together again. So that was one factor. Also, they changed the backing to a red maroon instead of the purple that had been there and a number of other things. Then, later on, about 20 years later when it was housed back in the Holley Manufacturing Building when Fred Leubuscher owned the buildings, there was another, much more major break-in. A number of knives were stolen — at least 52 were reported for insurance purposes, but we think there may have even been more stolen because the numbers don’t totally work out since there were originally 222 knives in the initial exhibition and we don’t have anywhere near that number now. A few of the knives were recovered, but most of them are gone forever. That’s what made recreating the original 1876 design almost impossible — trying to find all those missing knives.

The most recent iteration of the display wasn’t the 1876 design since that had already been changed. So, we basically made the decision that we would create a new design, trying to make it look similar to the original, keeping the original half arc shaping of the upper part of it, but we would create what would be basically a new design. It was a big decision within the Historical Society, we thought of every possible option of what we might do, and finally came to that consensus.

LB: We were very lucky to have detailed records of the original design, what knives were there and where they were placed. The last director of Holly Manufacturing back in the 1940s made an effort to try and sell the display to the Smithsonian Institution, so he did a great deal of documentation on the display case and all the rest. So, we did have some idea of what knives were in there and where they were placed. But to try and replace 100-year-old knives on the collector’s market, if we could find them, would have been prohibitively expensive. So, we made some tough decisions, but we also made those decisions trying to keep in mind the spirit of the original design as much as possible. We were talking about having to find an additional maybe almost 100 knives, you know, it just was prohibitively difficult for a variety of reasons, including the expense factor.

The newly conserved and redesigned display, 2024. Courtesy of the Salisbury Association.

Are there gaps where those knives would have been, or is the redesign supposed to look cohesive as if those knives weren’t there?

RR: The latter, actually. We wanted the design to have the ambiance, the feel of the original, but it’s its own unique and special design. We were pretty excited about how it came out. In addition to Fallon & Wilkinson that did the conservation, we had another firm, Level Fine Arts Services, who actually did the design work itself, and they consulted with us and we talked about the feel and the spirit we wanted to create in the design. And we think they did a really good job so that it looks remarkable, and it conveys the ambiance of the original exhibit without having any illusion that it is a recreation of the original exhibit.

We do have a picture of the original display so people can see and make a contrast between the original and what we have now. We acknowledge that original design quite overtly and concretely.

—Carly Timpson