Kristin Mizo photo.

In early October, the Decorative Arts Trust announced that it had chosen Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian Design Museum as the recipient of its Prize for Excellence & Innovation, for the museum’s upcoming exhibition, “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes.” Wanting to know more about this important exhibition, and why it warranted the honor, we reached out to Susan Brown, associate curator of textiles, who co-organized the exhibition with Alexa Griffith Winton, manager of content and curriculum at Cooper Hewitt, for the inside track on both the exhibition and what the award means to the museum.

What does the Decorative Arts Trust’s Prize for Excellence & Innovation mean for this exhibition?

We’re just so incredibly honored to be the recipient for the prize. It gives long-overdue recognition to Dorothy Liebes as a key figure in the development of American modern design. In the exhibition and the book, we are trying to demonstrate the degree to which she shaped the contemporary environment, as a public figure, a mentor and a promoter of the movement. While textiles were her primary medium, the Decorative Arts Trust Prize recognizes her contributions in the greater context of the lived environment.

What prompted the exhibition?

In spite of the highly collaborative nature of the design process, design history has tended to focus on the solitary, often male creator. Dorothy Liebes has been left out of the story of many important interiors, which typically, design only carry the name of the architect – although, at the time, she was probably more well known. We thought it was time to revisit some of those narratives. Also, while it didn’t prompt the exhibition, we were very fortunate that the Dorothy Liebes Papers – at the Archives of American Art – were recently digitized. They were published online in 2020, so we spent the pandemic delving into those. She worked with everyone and they’re so rich, I think they’ll be informing research and exhibitions for years.

What is her legacy? Who are some of the designers she influenced?

She was a significant influence on designers who came up in her wake, in the 1950s and 1960s. People like Florence Knoll and Jack Lenor Larsen, who ensured she had a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (today the Museum of Art and Design) in 1970, before she died.

But she was such an incredible educator and so clear in her articulation of the role of textile design that I suspect there isn’t a student of weaving in the past 70 years that hasn’t been touched by her work. Collections of her handwoven samples were planted like seeds at institutions across the country, and they continue to be used in teaching today at RISD, the Design Center at Philadelphia University, the Art Institute of Chicago, and many other programs.

Where does the exhibition’s title – “A Dark, A Light, A Bright” – come from?

Dorothy Liebes was nearly as famous for her color sensibility as for her textiles. She was a color stylist for a dozen different US brands – Lurex is the most well-known – and an authority on color. “A dark, a light, a bright” was her “recipe” for creating a successful color scheme for the home or in fashion.

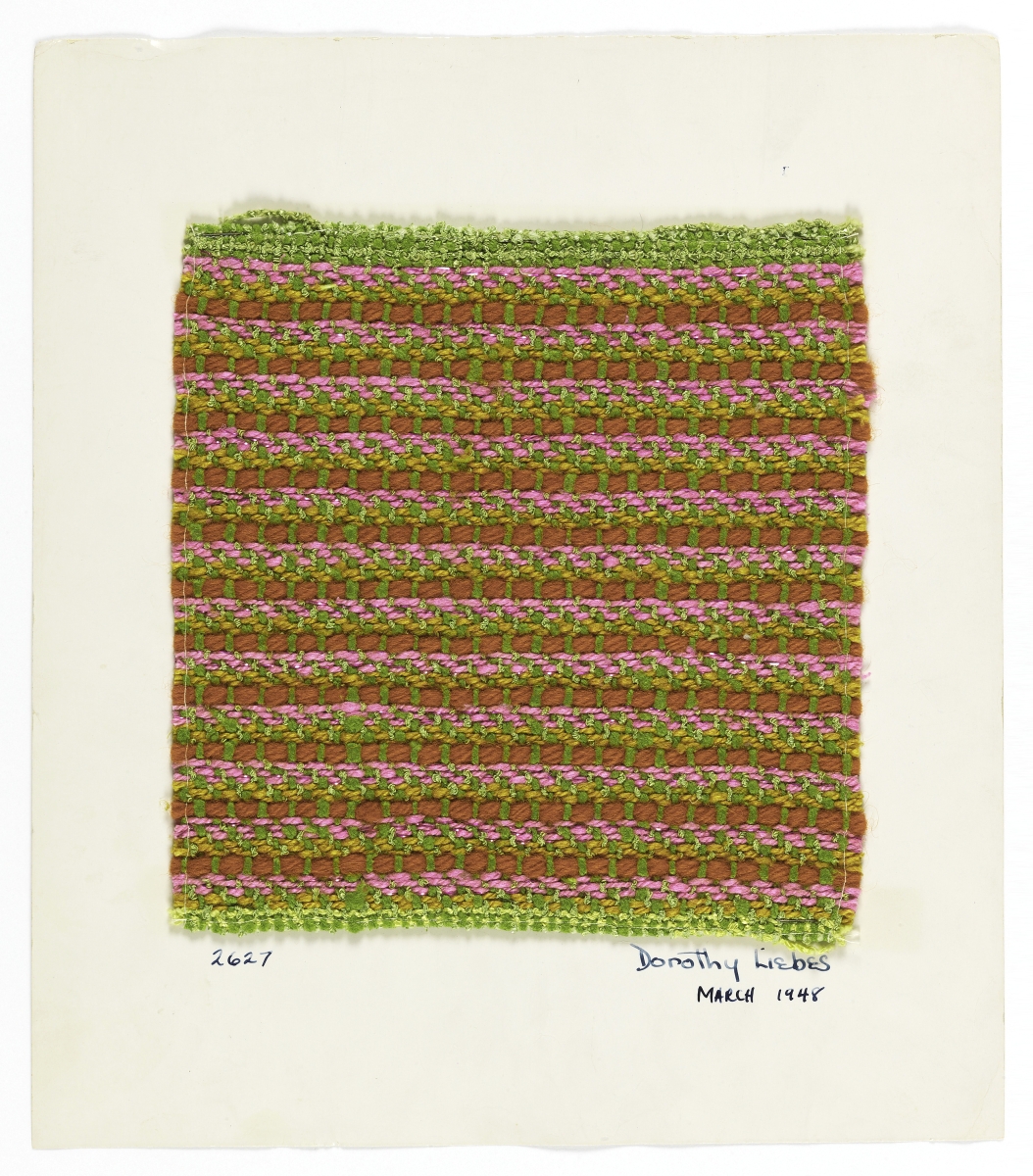

Sample card, designed by Dorothy Liebes (American, 1897-1972), 1948, twill-woven cotton, viscose rayon, silk, wool, cellulose acetate butryate-laminated aluminum yarn (Lurex), 12½ inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of the Estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Photo: Matt Flynn ©Smithsonian Institution.

Were there any surprises or revelations that you learned in the course of preparing for this exhibition?

I continue to be surprised by the contrast between the far-reaching impact she had during her lifetime and how little-known she is today. She was truly one of the most influential designers of the Twentieth Century, and deserves much, much greater recognition.

What do you consider her biggest contributions to the field of textile design?

She made contributions in so many ways, it’s hard to narrow it down to just one. Certainly, the continued appeal of the “Liebes Look wherever you see textiles whose beauty is derived not from pattern or complex structure but solely from an interesting and unusual combination of colors and textures, that’s Dorothy Liebes. Her influence in that way is seen everywhere in the design field.

Her work with DuPont was pathbreaking – she created a new role for the designer working with industry, and literally helped shape the materials other designers had to work with.

Because she was so present, in women’s magazines and shelter magazines like House Beautiful and House and Garden, many Americans’ experience of modernism was shaped by her. She did perhaps more than anyone else to advance the acceptance of modern design.

Her philosophy was “the simpler the technique, the greater the freedom for the imagination to play with colors and materials.” There’s nothing really technically complex about her fabric.

-Madelia Hickman Ring