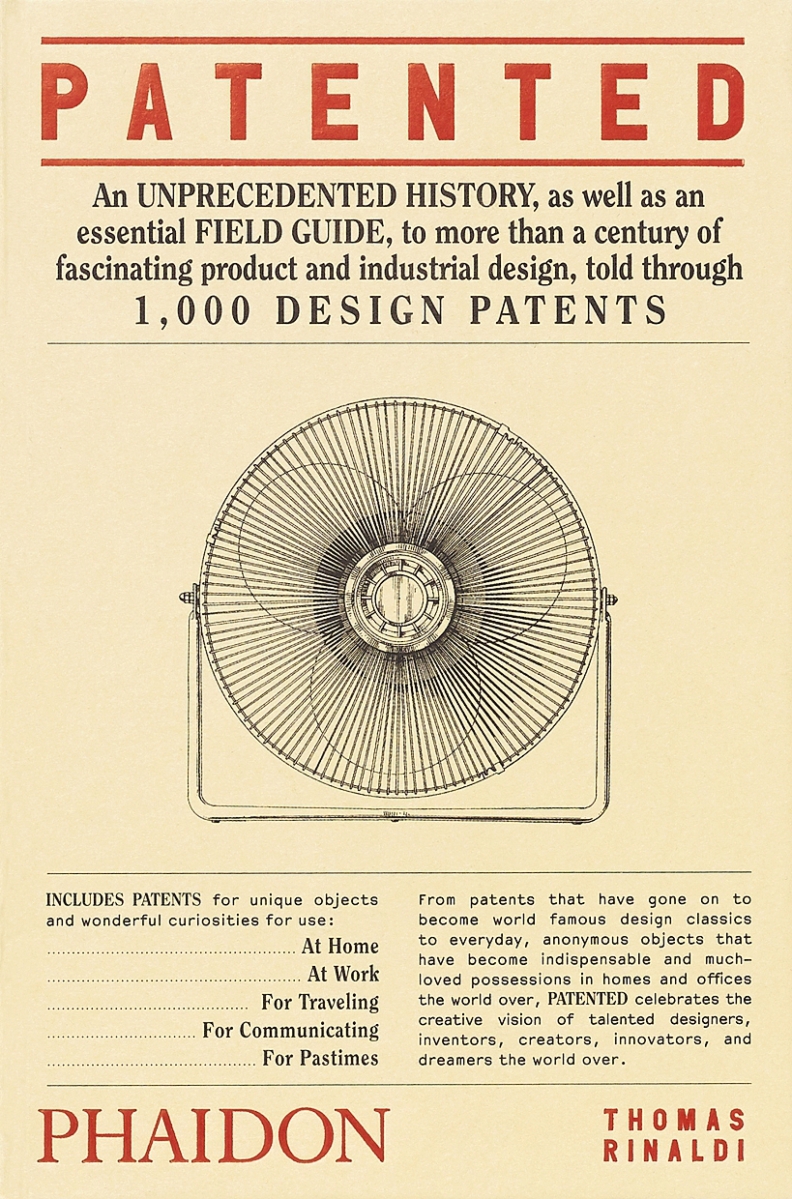

Everyone knows that person who can name every chair in the book, but you probably don’t know the guy who can name the designer of the tape dispenser, the pogo stick, the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile or the stapler – but not the Office Space stapler, that’s a sore subject. In his third book, author Thomas Rinaldi brings us 1,000 design patents from the archives of the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The selections range from the novel to the ubiquitous and from the mundane to the zany, with a healthy dose of levity thrown in. What intrigues most, though, is that nearly all of these products have surreptitiously established their presence in our lives – in our office, in our home, in our cars, basically everywhere we live – and they all have a story to tell. We sat down with Rinaldi to talk about Patented: 1,000 Design Patents and the icons of product and industrial design found within.

Are patents useful for design historians?

I would say they are enormously useful. I feel that many design historians have not yet realized that or are only relatively recently realizing that. Maybe if you got a room of them together, they’d say, ‘no, we’ve known about them forever,’ but I’m kind of a design historian and I didn’t fully realize their importance until recently. That’s partly because they’ve only recently been digitized. I had never thought of patents as anything that could inform a look at design history.

How accessible are patents to the public?

Pretty accessible, Google Patents is the most user-friendly of several online patents databases. The others are a bit more esoteric and are a bit harder to use. But even so, Google Patents is still buggy. I’ll search for something one day and it’ll turn up, the next day it won’t. When OCR scans these documents, if something scans wrong, it won’t come up. I had to really rely on searching for something repeatedly and keeping track of what I found and then using other websites that are more reliable but aren’t as user-friendly.

On the objects, sometimes the patent number is stamped on them, but that seems to not have happened much after the 1930s. Things made now don’t really have them at all.

Were there any design elements that gave you pause for their elegance?

There are some that I found arresting purely for their graphics. The patent office has guidelines that seek to make the drawings as standardized as possible. There’s very little room for artistic expression in them, yet there are some that are beautiful drawings even if the thing they’re depicting is not exciting. There’s a 1943 motion picture projector invented by Clarence Karstadt for Sears Roebuck & Company, I have never seen one in person but the drawing is remarkable. On the other side, there are other iconic things where the drawing is so lackluster I couldn’t use it in the book. That ubiquitous library step stool is one, that barrel-form step – everyone has seen that, but the patent drawing is a bit disappointing.

Patent applications are notoriously technical and not necessarily fun to read. Have you come to enjoy them?

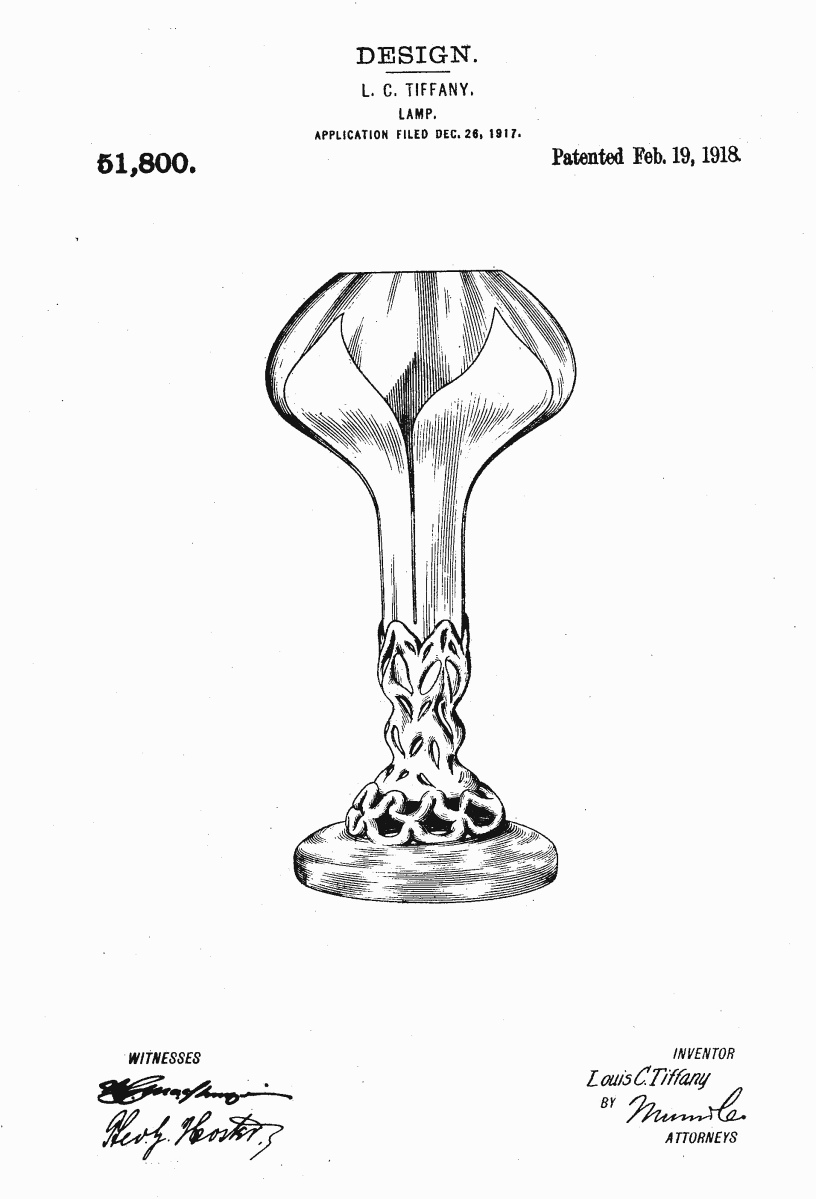

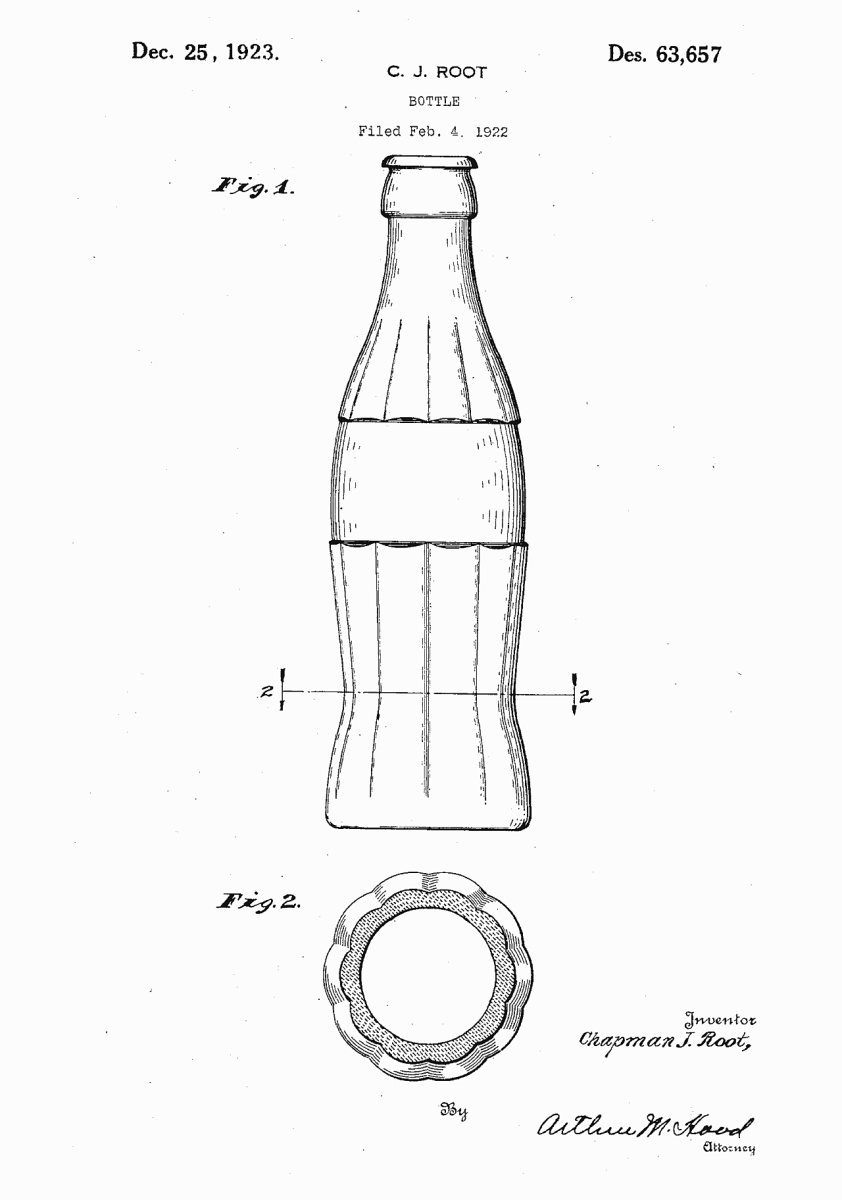

This book centers on design patents, which are different from utility patents in that there isn’t a whole lot of text with them. In a design patent, the text is mostly boilerplate: ‘I hereby attest that I designed this thing and the drawing attached.’ They’re more visual. Utility patents are a different animal. I wish that in 1842, when the government gave us design patents, that they had called them something different. It muddies the water that they are also called patents. It’s easy to confuse them with utility patents with the ponderous text and the technical drawings. The utility patent drawings are more engaging in some cases, but in more cases they kind of make your eyes gloss over, whereas the design patent drawings are simple, fewer in number, they don’t have key number tags. I was hoping that people will find the design patents engaging even if their drawings are a little more simplistic.

Did you find any unsung designers or inventors?

If you were to do the Jay Leno “Jaywalking” bit, I wonder how many people would know Henry Dreyfuss or Raymond Loewy. I think I discovered Loewy as a kid learning about trains. But you dig in and you see the other things they designed, and then to find out that there are a lot of people who were just as prolific as they were, but even as someone with an interest in design, I had never heard of these other designers.

Some that come to mind are Everett Worthington, he was active in the 1920s-30s and died suddenly of a heart attack. One of Loewy’s best-known designs is the famous Coke dispenser soda fountain. Worthington had that contract before Loewy, and had he not died, he may have been better-known. But he also designed toasters, radios, telephones – all sorts of things. He’s of this generation of designers before the streamline Art Deco period that were working in ornate and classically decorated designs with Greco-Roman and Classical motifs. And then he transitioned and was cranking out streamlined designs in the 1930s.

Another is Jean Reinecke, we have a number of his designs in the book, he was active from the 1930s through the 1970s. He designed tape dispensers and had a contract with 3M. There’s one he designed in the 1930s that you could still buy in CVS up until a few years ago.

Melvin Bolt is another, active form the 1930s through the 1980s, he did a lot of work for Zenith. He designed all these radios, but he also designed washing machines and a great flying saucer kitchen timer.

Many people in this field can tell you who made a chair or designed a light, et cetera. But you’ve taken it to a whole new level with household objects.

When I go to flea markets now, I see this invisible web. I used to go out to Dead Horse Bay, a sort of famous abandoned landfill in New York, and I’d see these things on the beach – ‘there’s that inkwell, there’s that Reinecke tape dispenser, there’s that beautiful streamlined bathroom scale from 1933.’ And the design patents reveal the obscure design provenance of so many of these things – in many cases those design origins are related in some way.

I imagine you know most of the things in your office.

My home, my office, I try to at least. I went with my father to Best Buy recently, and I’m looking all around the store totally fascinated by the design of all these things, wondering who designed what, whether I could track down their design patents…Even if they’re things I have no use for, I’m suddenly very interested in them. It was a bit confusing for the sales associates.

How have you organized the book?

Chronologically. Except at the beginning, we have ten case studies where we group things by typology. The bulk of the book is chronological and it’s that way because I wanted to emphasize that all of these objects of different typologies have a relationship with each other. It’s easy for someone with an interest in toasters or clocks to forget that they have a relationship with a lot of different types of products. Many of the industrial designers who designed those toasters or clocks also designed other things, telephones or radios or small buildings or parts of cars. We really tried to run a full gamut in the book. We have toilets by famous designers, toilet brushes, too. I also wanted to show how the stylistic evolution of these things transcends typology. The clocks and the toasters and the cars of the 1950s have a visual relationship with one another, and that relationship changes consistently as you go throughout the 120 years of the book.

There are more than 900,000 design patents, how did you go about selecting only 1,000?

I had a process – start with something interesting or important, something from the known pantheon of industrial design and work out from those things in a linear line of inquiry along two axes: one by designer and one by typology. For instance, I would take an Everett Worthington design for a telephone and work out on one axis collecting everything Worthington designed, and then on another axis collecting all the telephone patents. And then maybe also collect everything from the same assignee, or maker (they aren’t always named). There were intersections where those axes would intersect each other and create a kind of a web. I made a very detailed spreadsheet to keep track of all these things. I searched about 1,000 different designers, and I don’t even know how many typologies, and wound up with a shortlist of about 27,000 design patents through this process. I thought boiling those down would be easy, but it was so hard to cut things even at 1,000. I’d say, ‘How can we not include that!?’ all the time. But we couldn’t fit them all.

Do you think you’ll get through the entire USPTO archive some day?

I know I won’t. I’ve done so much that I had to stop. It’s addictive. I once tried to find the red stapler from Office Space, I spent so many hours. These kinds of little things beguile me, but I had to stop. So many design patents are filed every year now it would be impossible to keep up.

What’s the history behind patents?

It goes back to the Middle Ages and our patent system is modeled after the British patent system. The idea was multi-fold, it was not just to make sure that the person who designed something got the money they deserved, it was also to stimulate continued innovation by making these discoveries public – so people could know about them and take that idea and run with it. Design patents came along with the Industrial Revolution, when people were able to mass produce things. Design became important to these products. If your table was going to sell twice as many as someone else’s because it was a better design, you as the manufacturer of that table had an interest in the proprietary ownership of that design. At the time, the existing patent system was more geared to how things functioned, so it didn’t suit for protecting proprietary design. Manufacturers started to agitate for a change to the law that would allow them to better have a stake in the design of their products. This was notably visible with the cast iron foundries, they were some of the people agitating, especially in the 1840s. In the first year they issued design patents, only 12 or 13 were issued. It was a low number for a few years and then it started building.

How did you decide where to start?

We decided to start the book in 1900 and the best explanation for that is electricity. The advent of electricity really changed the nature of things that we used. The things before that are kind of fundamentally different in certain ways.

What are some of the iconic patents included in the book?

The Raymond Loewy streamlined tear drop shape pencil sharpener is one – it’s a lightning rod for design enthusiasts who either love it or hate it. In its day it was ridiculed. Why do you need an aerodynamic pencil sharpener bolted to a desk? But at the same time, it made it onto a US postage stamp. A prototype sold at auction for $85,000 in 2001. That was an iconic object even though it wasn’t manufactured. There’s the famous Model 302 telephone. Henry Dreyfuss is given credit for this (also on a postage stamp), but it wasn’t actually him who designed the first one for Bell Labs (it was George Lum). The design patent for the 302 was the clue that inspired the authors of a 2017 article in Winterthur Portfolio to snuff out the phones he actually did design. We have the Coke bottle, there were three critical bottle design patents to choose from and I ultimately picked the 1923 issue. We have the original Nintendo. The Tucker automobile – early in the pandemic, one of my early quarantine activities was to rewatch the film Tucker: The Man and His Dream. I went from that to what may be the least dynamic car ever made, but the one that saved Chrysler, the famous Dodge Caravan / Plymouth Voyager minivan, certainly an iconic vehicle for people of a certain age. The previously mentioned Loewy soda fountain Coke dispenser, so many are iconic.

I wouldn’t expect there to be so much international design, but there is. Tell me why.

We wanted to be representative of what has been design patented by the PTO and that includes a lot of foreign design. They have become staples of our everyday life and I wanted people to see things they recognized. It also speaks to the reality of globalization through history, it’s not new.

Casing, Leopold Jacobi for the National Cash Register Company, 1903-04. Patent Number: USD 36,767, U.S. Patent Office.

What is the impetus for international designers to patent in the United States?

A patent lawyer could answer this better, but I think the main motivator is the market here. Wherever you are in the world, you want to have a hold in the American market. American designers are filing for patents in other countries, too, it happens as globalization becomes more prominent.

Walk me through your favorite product evolution.

The cell phone comes to mind. It provided a real ‘aha’ moment. The thing that’s different about the cell phone is the typology covers a relatively short time span of 40 years compared to the others of 100-plus years. It’s interesting to see this product has had an evolution that is able to be studied in just a fraction of the time. I also like the fans, and I also like the coffee makers. They’re all pretty good!

Your favorite patent in the book?

Impossible question. The pig butt clock is always a favorite! I wanted to be sure that we had some levity in the book. I love some just for the way they look, the appeal of the drawings even more than of the design they depict. We included a number of patents from a company called AVCO, which became the parent company of Cincinnati-based Crosley, and it seems clear that these drawings must have been done by the same person, they have this great unique quality to them. We have a radio, a television, a washing machine and an electric range by them – the PTO didn’t allow patent artists to stylize their drawing, but there’s still a certain style that comes through sometimes.

Editor Note: Patented: 1,000 Design Patents is available for $39.95 at the Phaidon website: https://www.phaidon.com/store/design/patented-9781838662561/.

-Greg Smith