Dr Tiffany Momon founded the Black Craftspeople

Digital Archive (BCDA) in 2019. The BCDA aims

to set the historical record straight by compiling the

overlooked contributions of Black artists and artisans.

Photo courtesy Sewanee: University of the South.

As a graduate student who left a position at the accounting giant Deloitte to pursue a master’s degree followed by a doctorate in public history, Dr Tiffany Momon first explored American decorative arts at MESDA’s Summer Institute. Thrilled by objects but dismayed by the lack of scholarly attention to the contributions of African American artisans, Momon, now assistant professor at Sewanee: The University of the South, in 2019 founded the Black Craftspeople Digital Archive (BCDA), which she co-directs with Dr Torren Gatson, assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina Greensboro. Both experts are much in demand as voices on the Black experience. Momon is consulting on, among others, the upcoming exhibition, “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The BCDA, winner of the Decorative Arts Trust’s 2021 Prize for Excellence and Innovation, is meanwhile beginning work on a comprehensive Object Database, set to debut in 2025 as a companion to its directory of Black craftspeople.

How did your personal interest in genealogy lead to a doctoral degree and a new career?

I started looking into my husband’s family and wanted to put what I learned into the context of the African American experience in this country during the times in which they lived. I started a blog called Black Ripley, about his hometown in West Tennessee. When you’re doing genealogy and looking for your family, you come across the stories of so many other families. It quickly becomes a community story. My graduate level training as a public historian informs my teaching and my work with the BCDA. It’s important to me that I use my voice as a scholar, historian and as a Black woman to amplify as many stories as I can along the way.

As a graduate student in public history who had not previously studied American decorative arts, MESDA’s Summer Institute was eye-opening for you. Who was John “Quash” Williams and why was he the focus of your MESDA project?

Robert Leath, then MESDA’s chief curator, told me he had the perfect project for me, researching John Williams, an enslaved carpenter and joiner known in part for his work on the 1750 Pinckney Mansion, one of Charleston’s grandest pre-Revolutionary houses. It was a challenging project – the house was destroyed by fire in 1861 – but right up my alley. The majority of what I know about John Williams is me looking at him through the lens of the Pinckneys, because they are the ones telling his story. When I hear Williams’ voice through his labor contracts with Charles Pinckney and through the newspaper advertisements he placed, those are special moments because we get to experience, even if briefly, the world through his eyes. John Williams changed my life. I genuinely mean that.

Were MESDA’s well-known Craftsman and Object Databases prototypes for the BCDA? Are other databases, such as the William J. Hill Texas Artisans & Artists Archive, which is searchable by gender and ethnicity, or the Black Baltimore Digital Database helpful to you?

One thing we were very intentional about from the very beginning was testing our own research model. It’s important that our model pick up records of unnamed people because many Black craftspeople are simply listed by profession – carpenter, sawyer, etc. One of my favorite digital archives currently is the Colored Conventions Project. I also like Enslaved.org. The University of North Carolina Greensboro has People Not Property, a great example of an archive. There are many archives out there that speak to Black life and experience in the United States and from a digital humanities approach suggest best practices from which to learn.

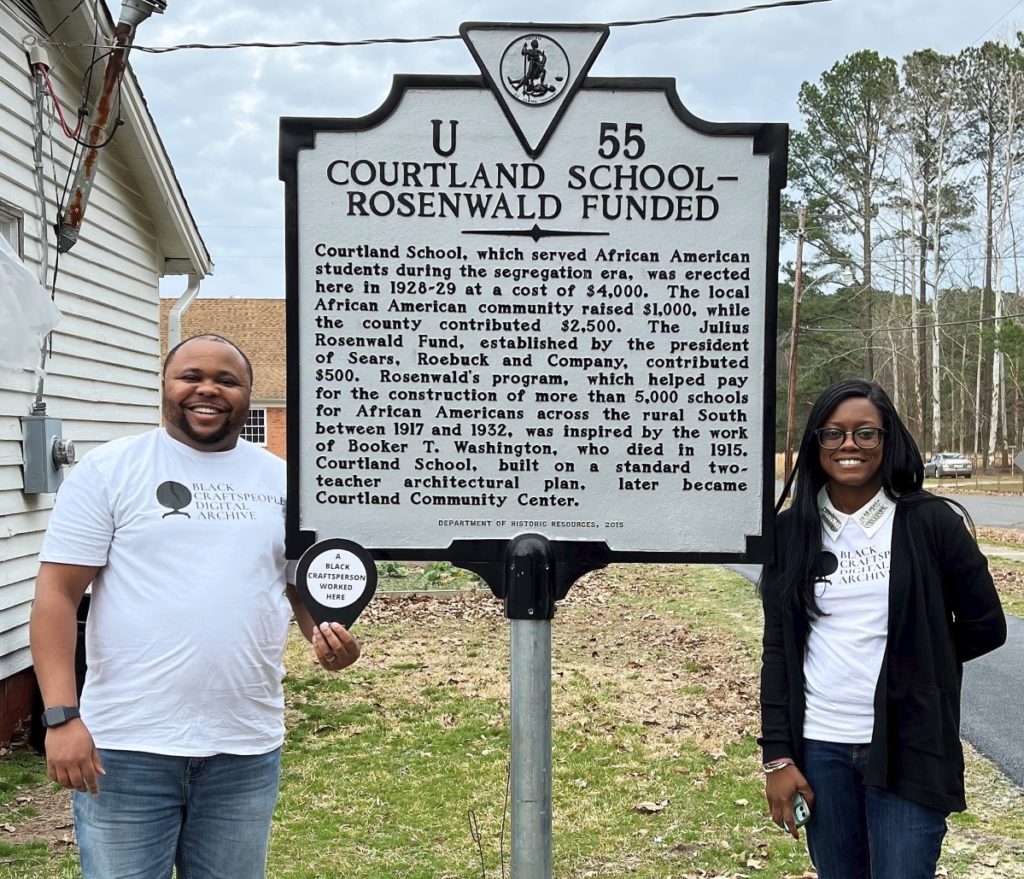

Torren Gatson and Dr Tiffany Momon, here at the historical marker for the Courtland School in Virginia, co-direct the BCDA. A UNC Greensboro professor, Dr Gatson holds “A Black Craftsperson Worked Here” sign, part of the BCDA’s popular online campaign to draw attention to its mission.

You are impatient with the curatorial excuse that Black material culture is understudied because the documentary evidence is scarce. What advice do you have for researchers?

What I tell people doing this research is that it is very location specific. You go to the documentary sources, but you may have to read between the lines or against the grain to catch mention of an enslaved person’s presence. Also, understanding historical context in different times and places is important and helps guide you to the right source material. For instance, in Tennessee one thing that helped the BCDA greatly was to draw from the 1870s US Census, the first to pick up all Black people. Newspaper references are good for an earlier period. This summer I have a student looking for mentions of Black craftspeople in private papers and documents held at the Tennessee State Library and Archives. Tennessee was engaged in the iron trade, so we will be looking at the iron plantations.

In New York, we relied heavily on sources such as newspapers, but we also looked at manumission society records and city directories because New York had a gradual emancipation law. Black people were freed over time and slowly began appearing in the documentary record. An unexpected source that worked well for us in New York was The Book of Negroes, compiled by the British [in 1783]. You can find it digitized online. It lists names of formerly enslaved people, says where they are from, provides physical descriptions and sometimes mentions who their enslavers were. Again, it’s knowing where to look for the information you seek to find.

How hard is it to match biographical detail with artifacts for the purpose of the BCDA Object Database?

At the BCDA we’ve decided to document everything thought to have a connection to a Black craftsperson. That speaks directly to our process of documenting the presence of craftspeople who went unnamed in records. Many museum objects are not attached to specific makers. Take, for instance, a handmade toolbox in the collection of the East Tennessee Historical Society. We don’t know the specific Black craftsperson who made that toolbox, but we do know it was made by an enslaved person on a plantation in Tennessee.

Are you encouraged or frustrated by the progress institutions are making in presenting a fuller, more accurate account of the American story?

I’m encouraged by what I’m seeing but also aware that there is much work to be done. I’m glad to learn of exhibitions such as “‘I Made This…’: Works by Black Artists and Artisans,” scheduled to open at Colonial Williamsburg in October 2022. There’s a lot of movement in the field.

An #ObjectOfTheDay on the BCDA’s Instagram page, these

“Stars and Stripes” slippers are attributed to Elizabeth Keckley (1818–1907), circa 1865. Fiber, leather and thread; length 10¼

by width 3 inches. Smithsonian National Museum of African

American History and Culture. The slippers were likely commissioned by Mrs Gideon Welles to be presented to her husband, Hon. Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy under President Lincoln.

You are much in demand as a professor, lecturer, consultant and program director. How do you manage it all? How important are partnerships to you personally and to the BCDA going forward?

Fortunately, much of the work I do is related. For instance, last semester I taught a class on the public history of Southern Appalachia. Our community partner was the Asia School Restoration Project, which is restoring a rural African American school in Franklin County, Tenn., where Sewanee is located, so there was significant overlap. I was able to talk about the things I love – historic preservation, building techniques, looking for underrepresented stories, working with community members – and bring students along for that ride. Dr Gaston and I are both public historians, so it is in our nature to be collaborative. Everybody needs to know these stories. There is opportunity to both amplify the BCDA and champion the work so many museums are currently undertaking.

Aren’t you also advising Classical American Homes Preservation Trust on its Roper House in Charleston?

My research as a historian is largely Charleston-based, so it seemed like a natural fit to begin looking for Black craftspeople associated with the construction of the Roper House, and to tell the story in a way where we begin to uncover the presence of Black craftspeople in the surrounding neighborhood. They are everywhere in the historic core of cities like Charleston. That greatly informs the approach to the research that Dr Gatson and I are doing on the Roper House.

Are students and interns part of the BCDA team?

We’ve been very fortunate in finding students, graduate and undergraduate, in Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina and New York who are interested in this type of work and can do it. New York is the first northern state BCDA added to its database. Two students needed virtual summer internships and asked if they could contribute. The answer, of course, was absolutely! Our New York interns were part of the Cooperstown Graduate Program and a joy to work with. We met virtually on a regular basis.

Jar by Thomas W. Commeraw (active 1796-1819), New York City. Inscribed on front rim of jar and filled in with blue glaze: Coerlears Hook New York. Stoneware; height 9½ by width 8½ inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund. Commeraw operated a kiln in Corlears Hook, along the East River between Manhattan and what is now the Williamsburg Bridge. The free African American potter is the subject of an upcoming exhibition at the New-York Historical Society.

Is a BCDA exhibition or symposium in the works based on the material you are uncovering now?

We hope there will be a symposium to bring scholars and the public together to celebrate when the Object Database debuts in 2025.

You are featured in the new film Craftspeople in Charleston. When will it be aired?

The program, a series of interviews with scholars and craftspeople, is a joint project of Classical American Homes Preservation Trust and the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art. I got to film at some of my favorite Charleston locations, including the Aiken Rhett House. It was a great experience. The film was shown in Charleston on June 9. I’m hoping it will soon be available for viewing elsewhere.

Parting words for our readers on the BCDA?

I’ll just stress that we’re a project that’s collaborative in nature. If you know about an object, or own one, that you’d like to share with us as we build the Object Database, please reach out. You can submit images directly via our website. You can also support the project monetarily by donating to our account through Sewanee: The University of the South or on our webpage. I have to give a special thanks to all who donated to the BCDA after the Decorative Arts Trust Award for Excellence and Innovation was presented at the 2022 Colonial Williamsburg Antiques Forum.

Editor’s Note: For more on the Black Craftspeople Digital Archive or to donate, go to https://blackcraftspeople.org or https://new.sewanee.edu.

To follow the BCDA on Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/blackcraftspeopleda.

-Laura Beach