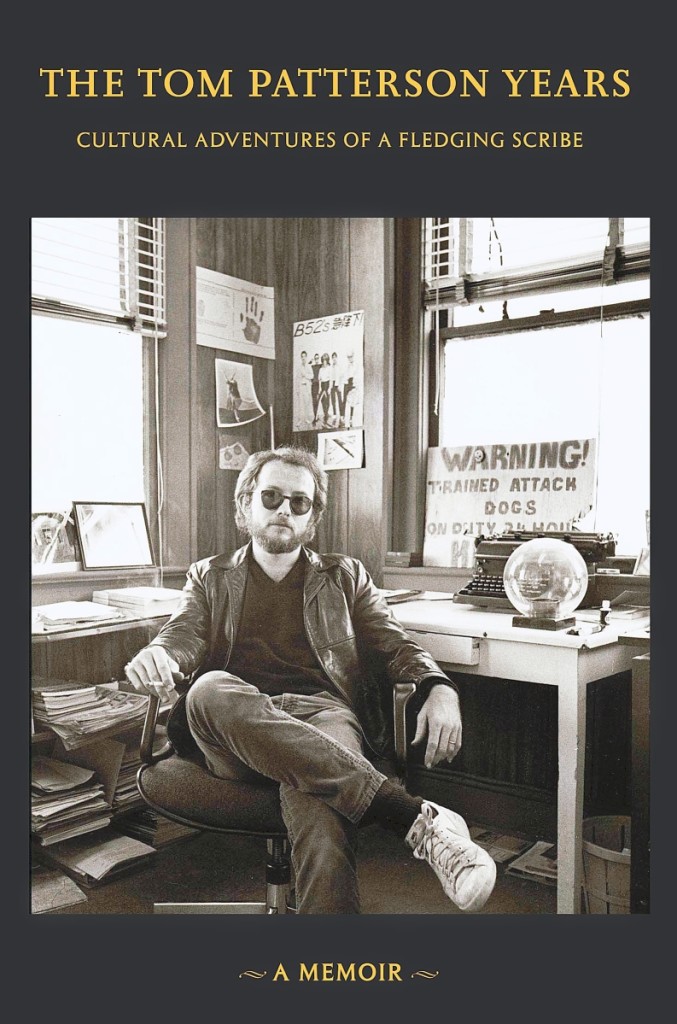

If you know vernacular art, you probably already know Tom Patterson. The writer has appeared in print since the 1980s when he started chronicling Georgia’s full-throttle cultural scene that was brewing icons of American art in figures like Nellie Mae Rowe, Howard Finster and St EOM – Patterson wrote the books on the latter two. The author has sat down to write another, an autobiographical memoir spanning three titles that documents his coming-of-age. The first installment, The Tom Patterson Years: Cultural Adventures of a Fledgling Scribe, is out now from Hiding Press, which gave us the chance to turn the table and start asking him the questions.

This first installment covers just seven years of your life? From 1977 to 1984?

Exactly.

Best years of your life?

I wouldn’t say that. This came out of a longer memoir narrative and this period was a convenient unit. I was going to start from this point anyway and kind of shift around in time.

What defines the era?

It’s my time in Atlanta. I moved to Atlanta when I turned 25. It was a pivotal time in my life, I was looking to get a foothold and establish some kind of career – and I wanted to be a writer, it seemed to make sense to move to a city. Atlanta was the city… I had never lived there, but I knew it well, having grown up in Georgia as a child and adolescent.

What did you do after you moved there?

I didn’t have a job out of the gate so I had to hit the ground running and find something. I had a number of friends there, I was able to crash in people’s guest rooms for a few weeks as I looked around for a job. I quickly found a newspaper job for a suburban weekly newspaper out of South Atlanta and I did that for a few months. Within the first year I was there I got a really good job with a travel/culture magazine founded by Alfred W Brown, called Brown’s Guide to Georgia. It was a pretty popular magazine in the 1970s and had a wide circulation. That gave me an opportunity to write about hiking in the southern mountains mostly. I quickly branched out to write about cultural subjects for the magazine and I did my first writing about so-called folk art, or what we now call outsider or vernacular art. I wrote about Jonathan Williams and he’s a major figure in this memoir – a mentor for me, founder of The Jargon Society and a student of Black Mountain College in the 1950s where he published his first book. He introduced me to St EOM and published my book on him and The Jargon Society funded my research on Howard Finster, which published in 1989. I worked for Brown’s for four years, 1978 until 1982, when the magazine folded, and then I was sort of back on my own resources as a freelancer. I had a reputation in the city as a journalist by that time, I was able to put together an income. I had a small press I ran, a nonprofit my friends founded and I took it over by the late 1970s. It was called Pynyon Press, we published about five books. We had a good little run there for about five years. We did three editions or issues of Red Hand Book, you can sometimes find those online. It was more like an anthology, an excuse to pull together interesting material under one cover. Poets, photographers, both literary and graphic arts. We had some well-known people, John Cage contributed, we had an interview with Allen Ginsberg.

The Tom Patterson Years: Cultural Adventures Of A Fledgling Scribe is available through Hiding Press at www.hidingpress.com.

It’s interesting you mention Ginsberg, because your scene reminds me of the Beats.

The Beats were factored into my education as a writer, I read all of those guys, Ginsberg, Kerouac and then the Black Mountain Poets Robert Creeley, Joel Oppenheimer, Jonathan Williams, John Cage, Merth Cunningham. I also knew Ginsberg and William Burroughs, though I didn’t get to know Burroughs too well until later on. There was a lot of cross pollination with that scene, but they were older. John Williams was of my parents’ generation and they were inspirational figures as a young writer in my early twenties or late teens.

It’s not all visual art in this memoir, you mingle with a number of musicians, writers and poets. Were the scenes all melded into one back then or were you jumping around?

They were kind of separate scenes. I was writing for a magazine called Art Papers, which started in Atlanta at the time – that was an outlet for a lot of my early writing.

Did the scenes all get along with each other?

It wasn’t too competitive. Later, reading about the music scene in Athens and Atlanta, apparently within those scenes they felt they were different, but I wasn’t interested in all of that. As a person following music, it didn’t matter. The Athens bands played a lot in Atlanta. The B-52s, they only had nine songs without a recording contract back then. They were this little weird band from Athens, I was so taken with them. I had a sense they would be big, but they certainly weren’t at the time. Then there was a whole explosion of bands out of Athens after that: REM, Love Tractor, Limbo District. In Atlanta you had Bruce Hampton and bands like the Swimming Pool Q’s and the Starving Braineaters.

Was there any single factor that contributed the most to the Atlanta arts scene back then?

It was a period of ferment, a lot of change. There was a lot of money for culture in Atlanta and that was because of the Carter administration in Washington. There was a Comprehensive Employment and Training Act that the Carter Administration had going, someone discovered you could get money for culture and pay salaries through that program. Then you had more from the Maynard Jackson Administration, Atlanta’s first Black mayor. This is after the Civil Rights era, Atlanta was about 65 percent Black population at then. It was a very hip urban Black scene, probably the most important urban Black scene outside of New York City at the time. Jackson had a sophisticated cultural affairs department in the city, so it was the coming together of the city and federal funds channeled into cultural organizations – that was an important time for the scene.

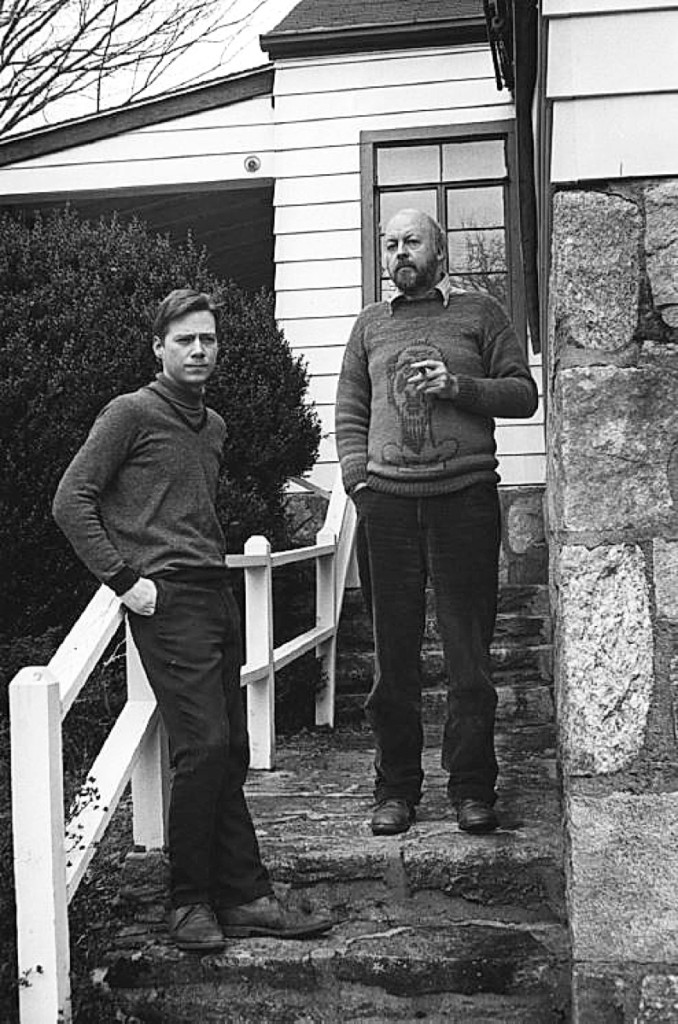

Thomas Meyer, left, and Jonathan Williams

wearing his Erik Satie portrait sweater custom-knitted by Astrid Furnival, Skywinding Farm, 1980. Photo by Tom Patterson.

Federal money is important.

Exactly. Almost everything that has happened in the art scene in Atlanta of any significance is built on the foundation that was established then. You can really trace that in visual art, institutional art, the new High Museum of Art was built in the early 1980s, they hired their contemporary art curator, then a few years later a folk art curator. They have a good exhibit on Nellie Mae Rowe on right now.

Did you ever see Rowe inside her house?

Yes, I interviewed her inside her house. That was in 1980 or 1981. I went to her funeral. The gallery who represented her was Judith Alexander, she made Nellie Mae Rowe’s reputation. Her work was incredible. Judith had been Jackson Pollack’s southern dealer in the 1950s.

How’d you wind up working for Judith Alexander?

I was a patron of her. She was editor of Art Papers for several years and I was a freelancer at the time, so Judith hired me as a part-time gallery assistant. I did that for that last six months to a year that I was in Atlanta. She was only open for about three days a week, she was trying to bring attention to these artists and if someone had a great collection, she would occasionally sell things to them. That was the first time I saw Bessie Harvey, no one who knew who she was, and Mose Tolliver. She had a great show of Bill Traylor, you could buy a Bill Traylor drawing for $300 in 1983. It was right after the Black Folk Art Show at the Corcoran.

What did Judith teach you about vernacular art?

She admired their self-taught style, spontaneous and so bold. The artists weren’t constricted, they were playing by their own rules. Judith didn’t care what you called it. She appreciated these artists as much as any other. Anyone that ever knew Judith will tell you she had an incredible eye. She would call me into the gallery sometimes and say, ‘Tom, you have to come over here and see this thing, I want you to tell me what you think.’ She would sit there looking at a thing for hours and hours and hours, I never knew anyone who looked at something as close as she did. She was a delightful character, just as eccentric as any of the artists she represented.

Your first experience with vernacular art?

It was the earliest art that I knew of. I was 6 or 7 years old when I started knowing these yard shows around the south. My parents were from Mississippi, and we lived in Georgia, so we would travel across Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi a couple times a year. This was before the major highways, so the routes went right through the middle of these towns and every now and then you’d see something unusual in someone’s yard. I remember my dad’s brother and his siblings lived in Aberdeen, Miss. Aberdeen was the home of Stephen Sykes, and he had this amazing thing he built on the outskirts of town, a three-story tower built out of junk. All kinds of found materials. From my memory, it was this towering thing, big and wide, it was kind of crazy, made out of pipes with scrap wood and animal skulls and hub caps hanging all over it. We would pass this thing going into Aberdeen and I’d beg my dad to stop the car, but he thought it was a crazy thing. When I was 7, I talked my grandfather into stopping and we met Stephen Sykes and he showed us around. He had a house nearby but he had a sleeping arrangement in the top of his tower. He would climb these ladders and sleep up there in the open air about two to three stories high over everything. That was a really important experience for me, seeing that thing and meeting the guy who made it. As a kid, the thing that struck me at the time was these adults seemed to have these dismal lives going to offices, so it was encouraging for me to meet an adult in his 50s who spent time doing things like this. It was before I had a concept of art, only the vaguest concept of what art must be. That had a huge impact on my aesthetic, I liked stuff that was all rusted and kind of broken looking. I was immediately interested in anything that had that kind of look, including the early Rauschenberg sculptures – and it turns out he was looking at the same things I was looking at, the same kind of source material. I had no language for it at the time, it was just this really interesting stuff.

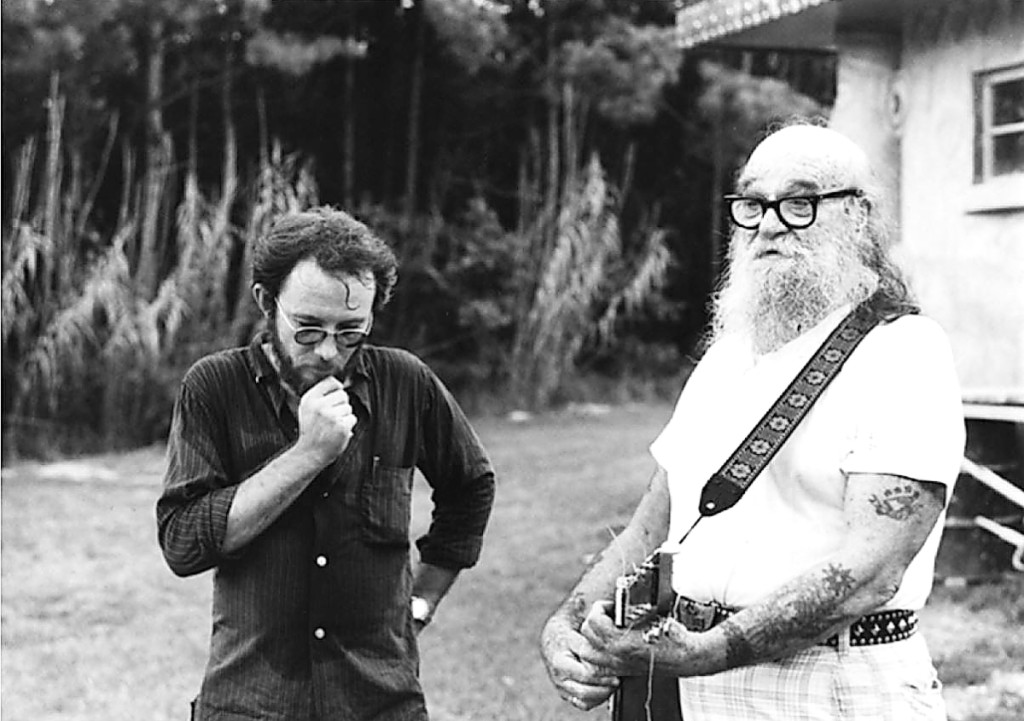

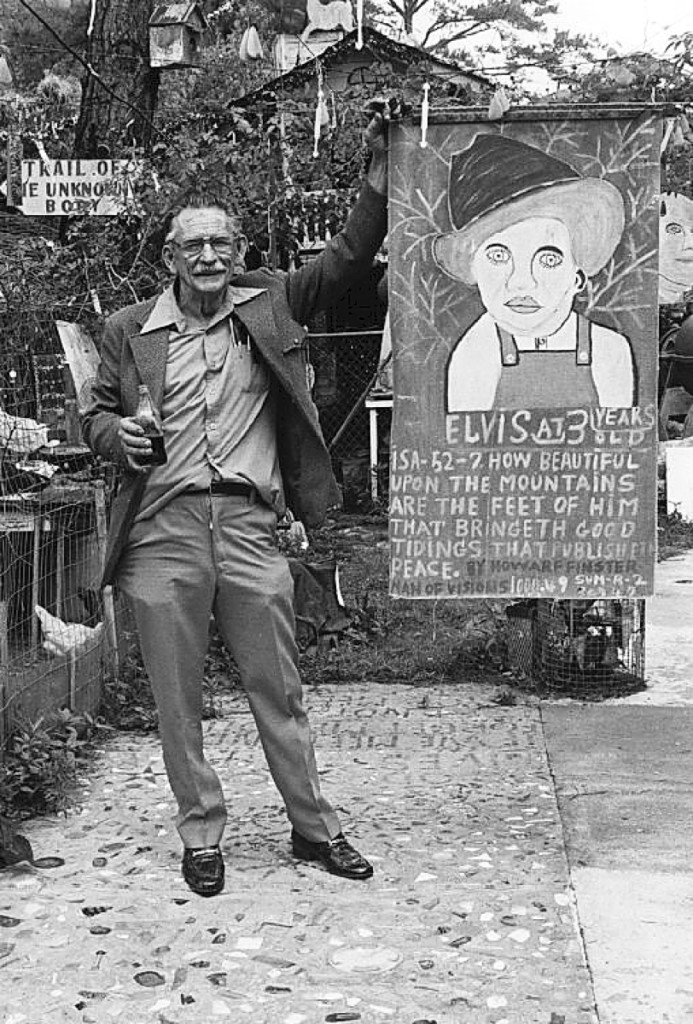

How did you come to know St EOM and Howard Finster?

They were known, but St EOM was a bit of a difficult character. If he didn’t like you right off the bat, he wouldn’t give you the time of day or cooperate with you. He made his living as a palm reader or psychic, that angle colored all the press I saw of him before I went there. There were decent pictures of Pasaquan, but I didn’t understand it until the first time I drove there with Jonathan Williams. That’s the first chapter of my book, looking around and realizing, ‘Wow this is serious, this is as serious as art gets.’ Pasaquan looked like something that took a bunch of people a long time to build. And in fact it did, he had hired locals to do some of the work. But it was an extraordinary vision and Jonathan Williams understood it.

Did going with John help you break in St EOM? What about Finster?

Yes, for sure, Jonathan knew him. Finster was much more approachable, in fact he’d approach you and he’d be talking a blue streak the entire time you were there. He was a known quantity, had a New York and Chicago dealer, he’d been written about in Life. In 1980 was when I first met him, but it wasn’t until the mid-80s that he was famous beyond famous, he was a celebrity on the Johnny Carson Show, he did a Talking Heads cover. I was working on that book at a time when Finster was on the rise.

Did you work on both books at the same time?

I started on the St EOM book in 1983 and started talking with Finster about doing a book at the end of that year. It was a couple years later when I got started. The St EOM was first, finished by 1986, and the Finster book was already well started by then. I lived in North Carolina by then, but I would drive down and spend several days or a week with Howard. He had a spare apartment he’d let you stay in. I’d tape record those talks. Howard was a real meanderer, he was all over the place. He was a difficult interview subject, you couldn’t ask him a question and he’d just answer it. You would ask him a question and it would make him think of a story, an hour-long answer. It would make great material, but it was so hard to keep him on track. He was a consummate multitasker, he had a television going in the studio and watching it with one eye, a brush in his hand painting, and he’d be talking the whole time. Someone might call him on the phone and he’d be doing everything at once. I’d go to bed in the wee hours of the morning and I’d wake up and he’d still be talking.

Was St EOM more guarded?

By the time we started working on his book, we had become good friends over the past three years. I had written a long magazine piece about him that he liked, it was almost all in his own words. So he wasn’t too guarded, he was actually no holds barred. By the time he decided he wanted a book, it was really his idea, he called me up and said he wanted to tell his life story and asked if I would help him. That was in January of 1983. I started interviewing him extensively for the book on his 70th birthday, July 4, 1983. I wasn’t judgmental about any of the stuff, many people he encountered in that small Georgia community were narrow minded, he couldn’t tell them about his experiences as a street hustler in New York in the 1920s. But by the time I met him, he was respected by the locals. His neighbors were kind of afraid of him because of his alleged psychic abilities and his abilities to communicate with the animal world. People kind of left him alone. He was treated with a certain amount of cautious respect.

Did those artists give you any advice that has stuck with you?

I don’t know any advice, I was just struck by their remarkable lives. With Eddie, his whole life is an amazing slice of the Twentieth Century. From Pre-Depression to the Roaring Twenties to the Post-Hippie era, and he encompassed that entire thing. He was an avatar in a way. Finster fled his traditional background, and a lot of that, I think, was because he was gay. He came up in a southern traditional background, embraced it and became a preacher. But then he veered off the rails, he’d be preaching and all of the sudden he’d start talking about a vision of traveling to outer space. A lot of people thought he was crazy. He wasn’t always respected, he had vandals trying to trash his property, shooting into his property. When I first met him, he packed a gun, he had people shooting at him. But then suddenly he was on Carson and was the most famous person to ever come out of that part of Georgia. Suddenly everyone was his pal. I always identified with St EOM, I always had a knack for non-conformists, the avant-garde. Finster didn’t set out to break rules, he just did, he was on his own visionary track.

Is the tradition of vernacular art still alive in the South?

There’s an incredible amount made in the South. The first big enthusiasts for artists like St EOM and Howard Finster were trained artists, people with a sophisticated art history background. It was the end of one era and the beginning of another. It reminds me of Greil Marcus’ Invisible Empire, originally titled Old Weird America, it kind of connects in with a lot of Americana music, the end of the do-it-yourself era – people weren’t connected through the internet. Nothing happens in a vacuum. All of these artists were all aware of the outside world, but now outsider art is a thing and there are artists who will market their work as outsider and have websites. No outsider ever calls themselves an outsider, so it’s a much more self-conscious situation now. I’ve made my living writing about art, the whole gamut from contemporary and Twenty-First Century, and I don’t make those distinctions. For me it was always about the individual artist and what they were doing, it’s still that for me. I’m glad there’s a huge support structure. The period I was writing about saw Bill Arnett and his Souls Grown Deep and the massive discovery that represents: a huge swath of American art had been overlooked. I was aware of many of those people. By the late 1980s, Arnett had jumped into the scene and spent the rest of his life as an evangelist of that work. It drove me crazy, but he was onto something and had a huge impact. That is a big difference between today and where we were. The Outsider Art Fair started in 1993, there were two or three New York galleries. There was very little activity. In 1981, I did a big article about Georgia folk art for the Brown’s Guide. When the article came out, Jonathan Williams sent me a typed list, he said, ‘Make copies and send it to everyone on this list, you may get a job at the New York Times.’ It was a one-page typed, name and address thing – that was the scene, everyone in the country who was interested was on that list. Now, everyone is interested, major collections and museums.

How influential was Jonathan Williams on your career?

Jonathan Williams was one of the great characters, it was like knowing Mark Twain. I picked that up instantly when I met him. I was a senior at St Andrews University in North Carolina in 1974. We put on a Black Mountain College Festival where we got Buckminster Fuller, Ed Dorn, John Cage and more to come down, all these people visited our remote campus over the course of a spring semester. It was an amazing experience as a student to be exposed. They wouldn’t just come down, give a talk and leave, they would come down and be a resident for a few days, have lunch, drive around, whatever they wanted to do. It was a great opportunity to be with these great artists and hang out with them. Jonathan was part of that mix, he came driving into the campus and you immediately noticed him. He was wearing a three-piece suit, was taller than anyone else, and had a deep voice. Then he would start taking these books out of the box, they were the strangest little books you had ever seen, people you never heard of. He was like this traveling medicine show and he stuck around for a few days, gave a poetry reading, an informal talk about The Jargon Society – the press he ran for all those years – and he gave a great slide presentation, the best slide show I had ever seen with images of Watts Tower, The Postman’s Ideal Palace, the Gardens of Bomarzo in Italy, just these amazing things you had never heard of. After the talk, I remember telling him about Stephen Sykes’ tower in Mississippi and he was immediately interested in it and knew of it. He was the first person I ever met who was interested in that, everyone else would have thought I was crazy. He made a big first impression as a student. We crossed paths a few times after that, but he was kind of one of these people I wanted to come back to when I did something. So that’s the way it worked out, we reconnected when I was a journalist and I was able to do a profile on him. Not too many people were paying him that much attention at the time. From that point on we were closely connected. As soon as he read the St EOM book, we put together this larger project to work on. He hired me to work for The Jargon Society, researching material.

That’s for the next book.

I’ve got the next memoir about three-quarters finished. It will be titled Way Out There and it covers the three years I worked for The Jargon Society, the period after I moved to North Carolina when I was finishing both books and curating my first exhibition. I spent three years doing research on southern vernacular art. We didn’t really have resources to do preservation, but we thought what we were doing was advocating. That was really one of the main things we wanted to see happen, to see Paradise Garden and Pasaquan preserved. We were able to advocate strenuously at a key time.

-Greg Smith