As African American issues take their place at the forefront of public discourse around the United States, we look to art and image to teach us historical perspective and to illustrate the timeline that has brought the nation to a point of reckoning and change. In addition to our ears, we are guided by our sight – perhaps the most important sense against the tyranny of injustice and inequality – that forms the basis of the visual record. The images streamed on news reels today retell a story that goes back centuries. Some of the symbols are eternal. We sat down with Tuliza Fleming, the interim chief curator of visual arts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, to talk about African American images in art through time and the museum’s initiatives to open doors.

In the pursuit of change today, is there value in focusing on the things of yore over the current flashpoint moment?

There is tremendous value in the process of evaluating our past as a means of understanding and addressing our present challenges. Until fairly recently, the history of the United States has been presented and interpreted through the Nineteenth Century lens of Manifest Destiny. This lens privileged the idea that the growth and expansion of the United States and the institution of capitalism and democracy as our core economic and political system was inherently benevolent and progressive. However, current events are forcing many Americans to reevaluate this simplistic historical narrative. People are asking why Native Americans, African Americans and Latinx populations are so disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 virus. They are realizing that the American legal and law enforcement system does not impart justice equally or blindly. They are beginning to confront the reality that systemic racism, inequity, racism, economic disparity and social injustice are imbedded within the fabric of our history and our culture.

One of the great values of knowing and understanding our history is that it assists us in understanding the context of our present and prepares us to make change in the future.

Can African American material culture help alleviate systemic racism?

An object or image can pose questions, document a moment, inspire thought, convey a message, embody the spirit of movement, and serve as a visual flashpoint of a cause. So, in the sense that material culture can serve to inspire individuals to engender change, I would say yes. We must keep in mind, however, that the process of alleviating systemic racism does not reside in the creation of signs, art or types of material culture. Rather, it rests in the hands of the individuals and institutions that perpetuate and benefit from these systems.

Do you feel the power of images are critical in building momentum for change? What images from the protests have stuck with you?

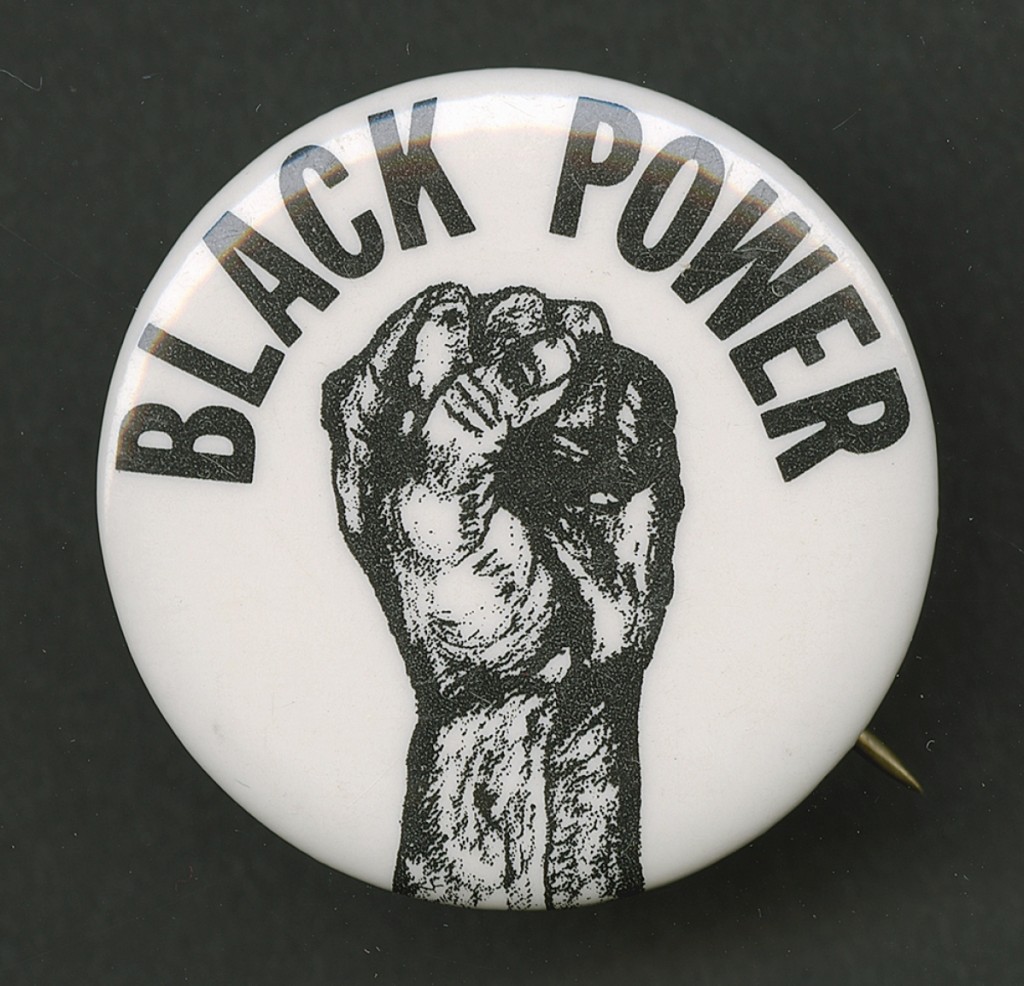

The critical role of the image in the mobilization of political and social movements cannot be overstated. Images have the ability to not only convey meaning, but they also embody emotion. Think of the enduring power of the raised fist. For over 100 years, the raised fist has been utilized by a wide range of international organizations and movements as a rallying symbol of resistance, justice and solidarity. Not surprisingly, the raised fist is a very prominent symbol and image in the Black Lives Matter movement.

For me, it is not the images from the protests that have stuck with me but the images that are, in large part, the catalyst for the protests. I am deeply haunted and sickened by the sheer volume of videos that I have seen where black men and boys are murdered before my eyes. To witness these horrifically violent and terrifying last moments of a person’s life is unbearable. I will never be able to erase them from my mind. I imagine that is how people felt when they viewed images of Emmett Till in his casket in 1955.

Pinback button promoting “Black Power,” 1966-1975. Metal, 1½-inch diameter. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Can you point to a historic artwork that draws a direct parallel from the African American struggle centuries ago to the Black Lives Matter protests today?

I don’t think that one can draw a direct parallel from images in artwork created centuries ago to what is happening now for a few reasons. I am assuming that when you refer to the African American struggle centuries ago, you are referring to the enslavement of black people. Although there were some artists who addressed the injustice and inhumanity of slavery, almost all of them were white men. I say this not as a criticism, but rather as an important consideration with regard to how one evaluates the viewpoint of the artist and message that he intended to convey. Within this context, it is important to understand that the makers of these images were not part of the community that they were commenting upon, but rather outsiders who were to varying degrees, sympathetic to the anti-slavery cause.

However, the NMAAHC owns a work by British artist Richard Ansdell (1815-1885) titled, “Hunted Slaves,” 1862, that we purchased precisely because it touches upon the process of self-agency and self-emancipation that is rarely found in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century images of black Americans. It depicts the moment when an African American man and woman who, during their attempt to escape from their enslavers, are attacked by three vicious bull mastiffs (dogs were often used by slave catchers to track their targets). In the scene, the man has already killed one of the dogs and is in the process of using his axe to defend himself and his companion against the imminent danger imposed by the remaining two animals.

One of the most salient and compelling features of this painting is the fact that the couple is not passively waiting for someone to give them their freedom but are active agents in the pursuit of their own destiny. This is where I would draw the parallel to the movements of today. Many African American men and women feel this constant tension between doing everything that we can to succeed and achieve the “American dream,” while simultaneously feeling physically at risk and systematically devalued. On a very basic level, what we see in Ansdell’s painting and in events happening on television today is that tension between those fighting for their freedom and the system that seeks to uphold the status quo.

You have a unique role that visualizes African Americans in art throughout history. How has the African American individual or experience developed as a subject through time?

This is a very difficult question for me to answer. I don’t think that it makes sense to distill the lived experience of millions of people over centuries into an “African American experience” visual trope. Another way to look at why this is such a fraught question is to ask if one can quantify how the white experience has developed as a subject throughout art history? It’s impossible to answer.

How did the selection of Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald to paint the official portraits of America’s first African American President and First Lady change the conversation?

The National Portrait Gallery’s decision to commission an African American man and woman to paint President and Mrs Obama’s portraits is very important historically and symbolically, especially for the general public. People who never really thought about art were interested in learning about these artists, looking at their finished creations, and if they were able, viewing the works in person. I cannot say how or if the conversation about the image of African Americans in art changed as a result of these commissions, however, I can say that I am pleased that the gallery chose to honor two artists whose work intersects with themes of internal and external identity politics.

-1024x605.jpg)

“The Hunted Slaves” by Richard Ansdell, 1862. Oil paint on canvas, 36 by 60 inches. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Should white consumption of African American self-taught art, with the market’s emphasis on a narrative of economic and/or social privation, make us as a society uncomfortable?

I do not think that anyone should be prevented or discouraged from purchasing art that they love made by artists who willingly choose to sell their work to the public, as long as the purchase is fair and equitable.

What should be done with historical material that depicts African Americans in blackface, caricature or within a racist stereotype?

The sheer amount of racist memorabilia that has been created in this country is quite astounding. Of course, some material has and should continue to be preserved to document the myriad of ways that popular culture has sought to erode black humanity. However, outside of those parameters, I am not sure what, if anything, should be done with that material.

What do you feel about the market for that material? Is it an example of white privilege?

I would say the original production, sale and purchase of these items are indisputably examples of white privilege. I think that with respect to the resale market for these items, that the issue of white privilege becomes more complex.

Tell me about the exhibition “Visual Art and the American Experience” that you have organized at the museum. What questions does it answer?

“Visual Art and the American Experience” is the museum’s inaugural art exhibition located in the Visual Art Gallery. Our former chief curator, Dr Jacquelyn Serwer, and I conceived of this exhibition as a way to highlight the important contributions of American artists of African descent through a historic and thematic lens. The exhibition explores subjects such as religion and spirituality, identity, struggle and protest, and history and heritage. The exhibition also represents the wide range of styles, mediums and movements that African American artists have utilized to express themselves visually.

I think that the questions that the exhibition answers depend upon the individual viewer. Whatever questions people may have, my hope is that they leave our gallery inspired, more knowledgeable, and with a greater appreciation of the role of art in our society and culture.

“Behold Thy Son” by David C. Driskell, 1956. Oil on canvas, 40 by 30 inches. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, © The Estate of David C. Driskell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York.

What are some of your favorite pieces in there and the lessons imparted with them?

As one of the gallery’s and art collection’s founding curators, all of the work in the exhibition has special significance to me. However, there are several artworks that I think stand out with regard to importing special significance to our history and culture.

One such work is a small plaster sculpture by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877-1968) titled, “Ethiopia,” 1921. Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s “Ethiopia” is widely considered the first pan-Africanist artwork created in the United States and a visual embodiment of the New Negro Movement – an era during the 1920s characterized by a marked increase in artistic and cultural production, racial heritage and pride, and political and economic justice.

W.E.B. DuBois and author and activist James Weldon Johnson commissioned Fuller to create “Ethiopia” for the Negro Exhibit in the America’s Making Exposition. An image of the sculpture graced the cover of the exhibit’s publication that read, “A Symbolic Statue of the Emancipation of the Negro Race.”

Fuller’s sculpture deftly reflected DuBois’ and Johnson’s interest in linking the achievements of ancient Egypt and Ethiopian resistance to colonial rule to a narrative of African American struggle and achievement. However, more importantly, it serves as testament to the fact that the concept of “black art” was a construct that was created and promoted by leaders of the New Negro Movement, not by artists themselves.

Another very important work that stands out in this time of civil unrest and protest is “Behold Thy Son” by David C. Driskell (1931-2020). Driskell created this painting in 1956, one year following the brutal murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year old who was lynched by two men who accused him of whistling at a white woman. Driskell created this memoriam to Till as a visual allegory. It is modern-day pieta that alludes to certain similarities between the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the murder and funeral of Emmett Till, and the religious foundation and galvanizing events of the Modern Civil Rights Movement.

When you view this painting, you cannot help but make comparisons to how the death of Emmett Till and the image of his mutilated body incited the nation to mass protest and how the video of George Floyd’s agonizing death is currently galvanizing the world against economic and social disparity and police violence.

Would you prefer African American art be regarded simply as American art, for art to be evaluated without the lens of ethnicity?

No artist’s work should be evaluated through the lens of race or ethnicity. We never talk about by white people through the lens of whiteness. We never ask if there is a white aesthetic or question why white artists don’t address their whiteness in their art. We see them as artists. That is what all artists deserve.

-Greg Smith