The pages of this publication are devoted to those who love to collect art and antiques, the trends they follow, and the often vast sums spent in pursuit of items that give the owner an intrinsic sense of joy by their mere possession. But what of those categories that many readers might think considerably lower brow, daresay “fringe” if you will? When word of Wendy Woloson’s newest book – Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America – reached our ears, it seemed an opportune time to pause and look at an area of material culture we typically overlook.

What inspired you to write ‘Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America?’

I come from a “stuff” family, which has inspired my work as a historian. My grandparents were antiques dealers in upstate New York, and I grew up being towed to flea markets on the weekends, and often helped my grandmother set up and run her booth at antiques shows.

So, it’s probably no surprise that my research interests focus on the history of material culture and consumer culture. Among other things, I’m interested in understanding why and how Americans became a nation of consumers, why, over time, we have bought the things we have, how we’ve integrated material objects into our lives, how these objects have recirculated beyond wholesale and retail exchange, including in used goods stores and on the black market, and what, ultimately, they mean to us.

While doing all this research, though, I’ve often felt a bit frustrated about scholars’ seeming lack of curiosity about the history of ordinary things. Because, after all, these ordinary things are the very objects that make up the bulk of our material culture and have, over time, formed the key artifactual record of the ordinary past. We’ve come to take these things for granted because, unlike the typical kinds of objects that people study, they are not remarkable. They often did not withstand the test of time, were not accessioned into the collections of museums and historical societies, and did not become precious heirlooms handed down from one generation to the next. But for this very reason – that the very ubiquity of cheap goods and the significant role they’ve played in the lives of average people – I came to believe that they, too, deserved to be taken seriously.

Your book reminds me of the quote “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure;” are there things universally regarded as crap or is that still a subject of some debate?

Ha, yes. For me, crap is not any particular genre of things or specific thing, but rather a state of being. Certain objects are undeniably crappy. They are inexpensive; made poorly and with shoddy materials; not meant to last; inefficient and ineffective; often things we don’t need or even want.

This is the way I put it in my book. Crap Confounds: Low-priced goods aren’t necessarily bargains. Crap beguiles: Gadgets don’t ease our burdens or miraculously cure what ails us. They often create more problems than they purport to solve. Crap seduces: Free stuff isn’t free, and the people who give it to us want not our friendship but our money. Crap feigns: Pieces purchased in gift shops are not unique works of hand-wrought art but are typically made in factories just like any other commodity. Their romantic backstories are fictions, too. Crap dissembles: Those mass-produced collectibles are not unique or exclusive. Nor will they appreciate over time. Crap tricks: Novelty goods do not help us participate in light-hearted play but implicate us in violence, turning otherwise dispassionate witnesses into perpetrators (those in on the joke) and victims (those who aren’t.)

Are any of us immune to accumulating or collecting crap? Are some people more prone to collecting or accumulating crap?

It seems to me from anecdotal evidence that there are two fairly distinct categories of people: the avid collectors and their often long-suffering partners, the non-collectors. But I don’t know the extent to which people who eschew collecting also reject other kinds of objects in their lives, like give-aways. Does the minimalist also say no to free t-shirts, magnets, pens, beverage holders, note pads and other promotional products? The stuff we’re given is especially hard to reject, because there’s this sense that if you turn down something that’s free, there’s something wrong with you.

I also think most of us have a pretty high tolerance for crap, and living in the late capitalist world of complete commodification and total surplus, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to resist the impulse to accumulate, whether we intend to or not. You often hear advertising appeals for gifts to give “to the person who has everything.” The correct answer is never that we should give them nothing. There’s always something more even “the person who has everything” can own.

What drives the need to accumulate crap?

I think it’s a confluence of factors. There are several different theories regarding amassing and collecting, but scholars tend to agree that having possessions is inherent to being human. We need certain things to stay alive (food, clothing, shelter). Other things provide us with convenience and comfort – petty luxuries that enhance what we need for survival (a more comfortable couch, a warmer coat, a more efficient appliance, and so on). Still other things can offer us psychological well-being and help us forge a sense of identity not only for ourselves but that we can convey to others. There’s a great quote from William James that I think is relevant: “a man’s Self is the sum total of all that he CAN call his, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes and his house, his wife and his children, his lands, and yacht and bank account…If they wax and prosper, he feels triumphant; if they dwindle and die away, he feels cast down.” Russell Belk, a highly regarded scholar of consumer psychology, considers possessions part of our “extended self,” and I agree.

In the past, before mass production, people owned fewer things and tended to be more thoughtful about them. People kept track of everything they owned and items often served multiple functions. For example, a piece of furniture used as a worktable to ply a trade during the day might be converted into a bed at night; articles of clothing that were outgrown or outworn would be taken apart and literally refashioned to create new items to wear; a pocket watch could help tell time, serve as an outward sign of status, be used as collateral for a pawnshop loan, eventually become a cherished heirloom if redeemed, or broken up and sold as raw materials if not. As your readers well appreciate, these things were made out of sturdy materials that could be reshaped and reused and handed down over several generations, becoming like members of the family.

How did mass-production change things?

Over time, and especially by the later decades of the Nineteenth Century, consumer goods became cheaper and more accessible, flooding into American markets and made domestically. What was more, due to more sophisticated techniques of advertising and persuasion, people gradually adopted a new consumer-based ethos that not only privileged consumption over production, but also enculturated people to value not older objects that had withstood the test of time, but newer items instead. As part of this, people came to believe that one’s consumption preferences reflected one’s tastes, one’s class, one’s interest in and ability to keep up with the “latest fashions,” and hence, one’s social standing and group affinity.

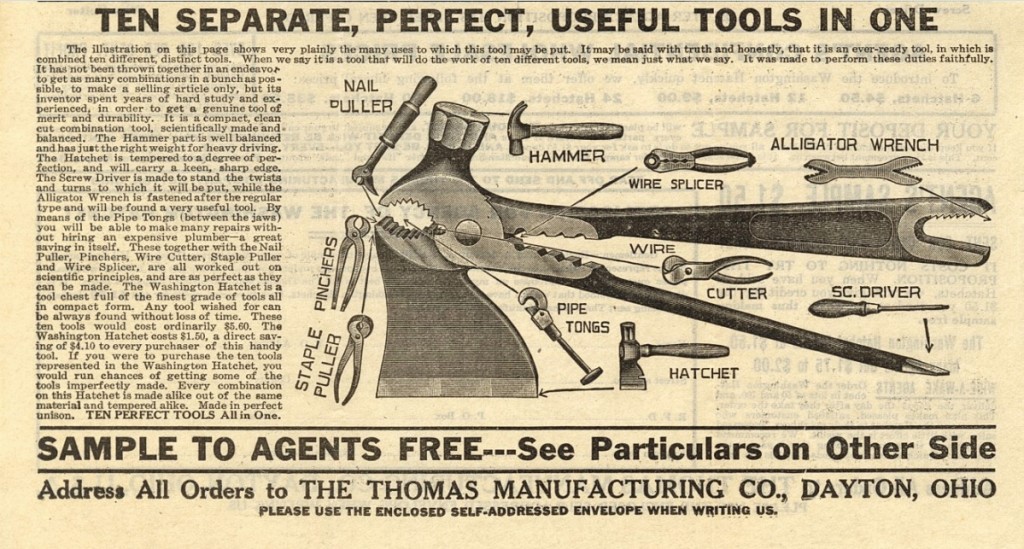

An example of “extravagant futility,” multi-tools promise to do a variety of things, but typically don’t do any of them very well. Claiming to be ten “perfect” tools in one, the Washington Hatchet shown here was manufactured around 1900, but these gadgets remain wildly popular today.

And today?

Today, our consumption of cheap goods has become a self-reinforcing cycle. The seemingly insatiable drive for more and more cheap stuff has put a lot of American manufacturers out of business, since the price of their better-quality products tended to be too high and we can now readily buy cheap stuff from China. Outsourcing in turn has led to the closing of those factories and the decline of good-paying jobs, which in turn has resulted in people only being able to afford these cheap goods. So now, crappy things are often the only ones available to us to purchase, and the only things economically within reach. At the same time, we continue to embrace novelty and the perpetual cycles of fashion, plus we continue to see consumption as an entertaining diversion rather than a necessary activity. So, we keep buying more and more stuff, most of it cheap and crappy. The heart of my book tells a much longer history of all of this – how we arrived at where we are now, economically, culturally and psychologically.

Is there an upside to collecting crap?

There have definitely been upsides. Access to cheap goods has enabled American consumers of all classes, over time, to fully participate in the marketplace – which is not simply the world of goods but the ideas and possibilities those goods represent. In addition, the taste for cheap goods has boosted the output of manufacturers, thereby helping to raise the general standard of living. Producers were able to employ more workers to make their wares, wholesalers expanded networks to distribute them, retailers could hire more clerks to sell them, and so on. Facilitating access to cheap goods also spurred the government to invest in infrastructure, especially early on: networks of turnpikes, canals and railroad lines not only connected people to once-distant markets but also made possible new ways of doing business, like the mail order enterprises of Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward. On a personal level, the vast majority of American consumers could embrace novelty for its own sake and for the pleasures it provided.

Cheap goods also brought more convenience to people’s lives in the form of “new-fangled” gadgets, from lightning butter churns to miracle food choppers. And, of course, cheap knickknacks and chromolithographs – initially made available by traveling peddlers selling plasterware figurines and printed materials – enlivened people’s homes, helped uplift their spirits and gave them necessary diversions.

Although impossible to quantify, it’s undeniable that access to a greater variety of affordable consumer goods benefited people’s lives. That said, I think we also have to consider the attendant costs of the crappiest of those goods, which I discuss in the book’s epilogue.

The craze for mass-produced collectibles like the ones shown here began in the mid-Twentieth Century. While they have enabled people of all demographics to experience the joys of collecting and connoisseurship, they rarely if ever appreciate in value.

Sounds like there are downsides to crap?

There are many downsides. First, because most cheap things today are made out of plastic and not meant to last, they are responsible for untold amounts of pollution. Such goods are disposed of at fairly high rates, ending up in landfills or trash gyres in the ocean, which are comprised of trillions of pieces of plastic garbage. And unlike cast-offs of the past that were made of wood or cardboard or cloth, these goods cannot be recycled into something useful and do not become cherished items in people’s collections.

There’s more, too, of course, including labor exploitation. Most of the crap we buy is inexpensive. And to manufacture something with a low price point means investing as little as possible in labor costs. This was as true for the exploited child laborers making Staffordshire figurines for the Nineteenth Century market as it is for the countless numbers of people working in overseas factories today, churning out everything from ballpoint pens to polyester scarves. And then low-paid workers in the West are put in the service of selling that crap, stocking shelves and tending cash registers for big-box retailers.

There are also less concrete but no less important implications, like the impact of cheap goods on the way we communicate. Much of what we say (and think) about ourselves, whether intentional or not, is through the language of goods: as markers of taste, status and culture, the objects with which we choose to surround ourselves can convey, quite powerfully, messages about self and other. What does it mean if the objects that chiefly comprise our language of goods are cheap and shoddy things? Further, what happens when the language of goods is not just the language of commodity capitalism, but a dialect that is particularly cynical, dishonest and crappy?

In your introduction, you say “crap deserves to be taken as seriously as fine art and antiques.” What are some of the reasons for that?

Well, first, because there’s so much of it. Most of us aren’t fortunate enough to be able to surround ourselves entirely with highly crafted thoughtful pieces. Works of fine art and antiques are rarities, often quite expensive and hard to come by, and require a sense of connoisseurship to fully appreciate, as your readers well know. While average Americans might possess a handful of nice things, our material universe, for the most part, is comprised of crappy stuff. So, it also deserves our attention because it is our stuff. And much like the way masterpieces capture and express elite sensibilities over time, so too do cheap goods chronicle a vernacular intellectual history. Although these things are often disposable, poorly made and unwanted, they play an important role in our lives and, for better or worse, reveal a lot about who we are as individuals and as a society.

Editor’s Note: Wendy A. Woloson, Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America, University of Chicago Press, 2020, $29.99.

-Madelia Hickman Ring