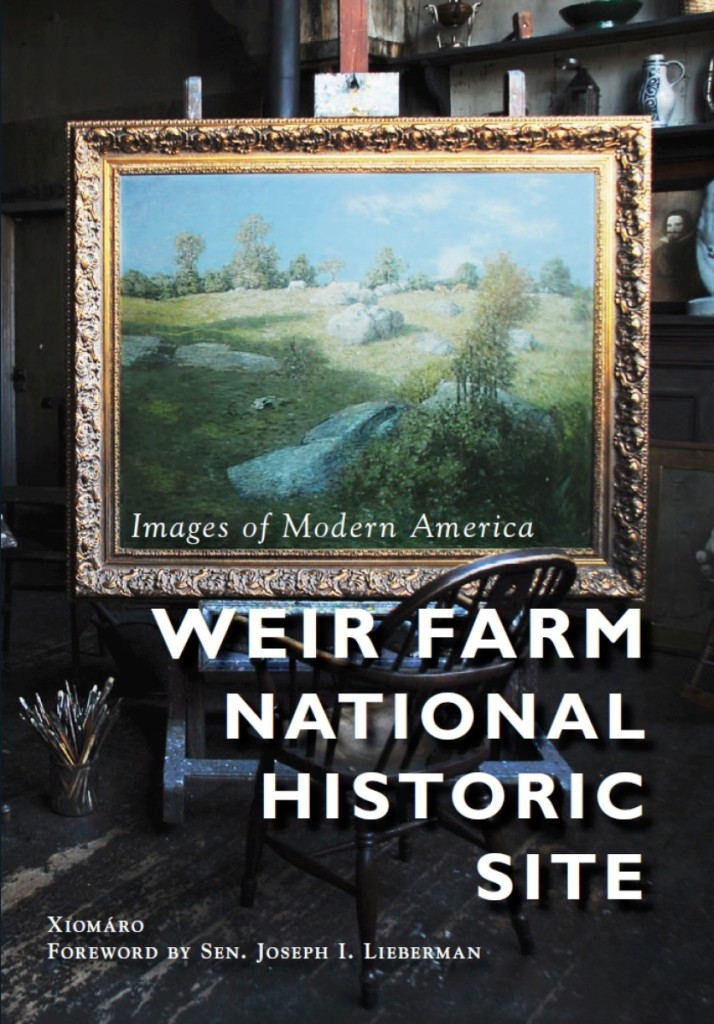

Xiomáro was not always a visual artist – a prior life saw him working in entertainment law for musicians while performing with his own band. That all changed when cancer knocked on the door, and while he would win that battle, the artist was indelibly changed when during his recovery, he picked up a camera and began snapping photos in the American West. “Since I have a reprieve and another shot, let’s see if I can do things a little differently,” he recently told Antiques and The Arts Weekly. His curiosity eventually led him to an artist-in-residence program at Weir Farm, a National Historic Site run by the US Park Service on the border of Wilton and Ridgefield, Conn., dedicated to preserving the studio of American Impressionist artist J. Alden Weir and the artists who created on that property after his death. Xiomáro was given access to Weir Farm unlike any other before him, and his new book, Weir Farm National Historic Site, offers the kind of photographic visuals that you can savor. The book releases ahead of the US Mint’s “America the Beautiful” series, which puts Connecticut’s first national park on the tail-side of the state’s latest quarter. We sat down with Xiomáro to learn about his work at Weir Farm and other historic homes throughout the United States.

What year did you start your artist-in-residence at Weir Farm?

In 2011. The park was open, but the buildings were not, the park service was in the process of renovating them. The buildings opened in 2014. Before that, people could come and walk the grounds and see the exteriors, but they could never go inside.

Tell me about the residency.

It changed my life, I had never even heard of an artist-in-residence program before it. I got an email one day from the AAA, and they were recommending Weir Farm for a day visit. I had never heard about it before. I went up there one summer day, and I took a tour to get a handle of the landscape. During the tour, they kept mentioning the artist-in-residence program, so that got my interest going. I thought if I could get in, it would give me a credential, it would give me time to propel my interest in photography, it would give me a month living in isolation in this park where I could really focus and figure out what I wanted to do. So I got in and lived in this historic cottage at Weir Farm for a month, and I ended up just photographing the grounds, because I thought it was beautiful. During an in-studio visit, which is part of the residency, a visitor walks in and it was Weir’s grandson. He came and he looked at my work and he liked them. He could tell I was genuine in my appreciation for the park and the buildings, able to detect that from the nature of my photos. He asked me if I wanted to see the inside of the buildings, so he arranged it with the park service where two of their staff members met me up there on a Sunday and they gave me a personal tour of the interiors. It was fascinating to see these nearly empty rooms by myself and I took some photos of them. But they were more for my personal documentation, they weren’t properly taken. In fact, many of them came out bad, some of them were blurry, it was pretty dark in there and many of them were fast pictures. A couple months after the residency ended, the park contacted me and said they were interested in the photos I took inside the buildings. I said they were welcome to them, but they didn’t come out well. Fortunately, the park staff also liked my photography, and as a result they decided to formally commission me to take proper pictures with the time and access I needed. The residency was pivotal in that way, I’m grateful for that program.

Xiomaro’s new book Weir Farm National Historic Site is available at http://www.xiomaro.com/books.

What’s your favorite place there?

I liked the pond. It’s a very peaceful, beautiful place. The grounds themselves are very beautiful. When you’re there, you feel like you’re somewhere else. But it’s not far from New York City or Danbury or Hartford.

There’s a good story about the pond.

Next to painting, one of Weir’s largest passions in his life is fishing. He’s a consummate fisherman. His painting, “The Truants,” won first prize at the Boston Art Club in 1896, which came with $2,500 in prize money. And the first thing he decided to do with it is dig this pond, to have this pond built in walking distance from his home. And from there he stocked it with fish, and then he had a dock built with a boat and would go out there and fish. It goes to show you that as a creative person, Weir didn’t just stop within the parameters of his canvas, he took his creativity to the landscape and created that in his own image.

And it all could have been lost.

This place could have just been another development. In 1963, a developer wanted to tear it all down and put up a 100-resident development – they were going to rename Weir Pond and call it Thunder Lake. That would have been so inappropriate.

But it fortunately went the other way.

Yes, today they’ve restored the grounds the way it was during Weir’s time, even going so far as to take down trees that weren’t there during his life. In the book, we have photos side-by-side; my contemporary picture next to one taken 80 years ago, and they’re almost identical. It’s a rare thing. And it’s also rare among artists, there are few out there that are intact like the home of J. Alden Weir. It gives the opportunity to walk in the same places that he walked, and also his contemporaries like John Singer Sargent, and to see the same things he saw and to try to draw inspiration from the same scenery.

A bird’s-eye view of J. Alden Weir’s studio. Xiomáro shot this by climbing up on a water tower that is closed to the public. He notes that the workspace is virtually intact since Weir died in 1919.

How does Weir come to own the farm?

Probably the real estate deal of the century. There was a fellow named Erwin Davis. He was a wealthy mine-owner, but he was also an art lover. And having this disposable income, he was able to hire Weir to go to Europe and scout out works of art that Weir would buy on his behalf. It was also a way for Weir to make extra money. During that same time, Davis bought the property that we now know as Weir Farm. He bought it because it was very close to the Branchville railroad station that goes directly into Manhattan, so while the property was out in the middle of nowhere, he could get to the city fast, which is where he did business. A couple years later, Weir gets married and starts looking for a property. At the same time, Weir buys a painting for himself for $560. We’re not sure what it was, but Davis saw this painting and said he had to have it. They struck a deal where Weir gave the painting and $10 to Davis, and in return he received this 153-acre farm. Weir had an apartment in the city, but this was great, he could get away and paint. So Davis got that painting, Weir got the farm, and there we are.

I wonder what that painting was.

We don’t know. There are various perspectives, differing accounts describe it featuring a flower and another describes it as a vegetable.

What impression does being in an artist’s environment impart?

When you go to the museum, you see the painting, but you don’t get to see the location that the painting was painted. Now that the building is open you can go in and see the brushes that he used to paint. That’s a moving experience.

And Weir wasn’t the only artist there, right?

A lot of people don’t know, but his son-in-law, who he actually never met because he had passed away by then, was artist Mahonri Young, and he married Weir’s daughter, Dorothy Weir, who was a legitimate artist in her own right. But Young was a well-known sculptor, his grandfather was Brigham Young, second president of the LDS Church and first governor of Utah. So he was often commissioned by the Church of the Latter Day Saints to create monuments that would be installed in Utah. One of them, “This is the Place,” is the largest sculpted statue in Utah. So it’s more than just Weir, it continued with this second generation. And then there’s a third generation after that, Sperry Andrews, who bought the property from Mahonri Young. Andrews was also an artist. And today it continues through the residency program. It’s a place that, for well over 100 years, has been creating art continuously.

-1024x1024.jpg)

To be released in April, 2020 as part of the US Mint’s “America the Beautiful” series, Connecticut’s next state coin will feature it’s first National Park, Weir Farm.

And you have worked with other National Parks and historic homes.

I’ve probably worked with a dozen different parks at this point. Sagamore Hill, like I mentioned, which also served as Roosevelt’s Summer White House. That’s on Long Island. I’ve also been doing work with the site of George Washington’s Headquarters in Morristown, N.J. There’s also the home and office of Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of Central Park. There’s the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, I’ve photographed his residence. It’s in Cambridge, because he taught at Harvard, so I photographed specific parts of the house that inspired specific lines of poetry. It gives people an insight into how a work was created. Another home was William Floyd, a mysterious founding father, he signed the Declaration of Independence and was a general that served under George Washington. But unfortunately the British took over most of Long Island where his home was located and most of his personal effects have been destroyed and lost. His home is significant because it’s one of the few plantations in the Northeast, and we know for a fact that Madison and Jefferson used to frequent that house.

So it seems like your work creates a modern visual context to illuminate historical creation.

Yes, I think that’s a large part of it. History, at least when I learned it, was kind of dry. It’s hard to imagine what life was like back then. So when I take the photographs, I want people to see into their life. In the book I have a closeup of the doorknob to Weir’s bedroom, and we know that it’s the same one he touched. In Sagamore Hill, I photographed the very room that Roosevelt slept in. And I took a lot of photographs of his bathroom, looking at the shower and toilet that he used. It takes it to a whole new place, beyond the presidential Teddy Roosevelt, but Roosevelt the mortal. Or Weir the artist. That’s what it does to people, gives them a sense of who these people were and how they lived.

Xiomáro’s new book, Weir Farm National Historic Site, is available at http://www.xiomaro.com/books.

-Greg Smith