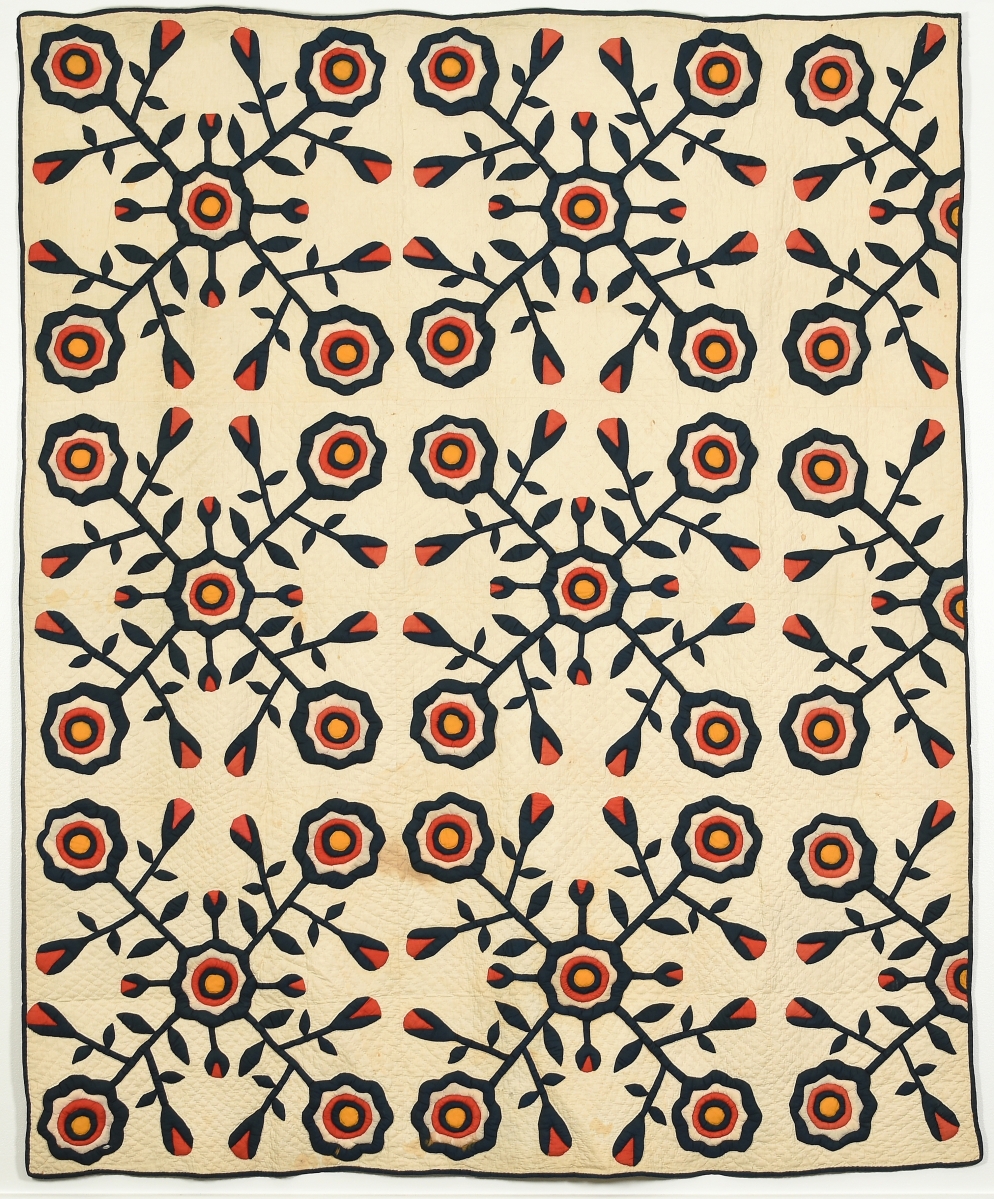

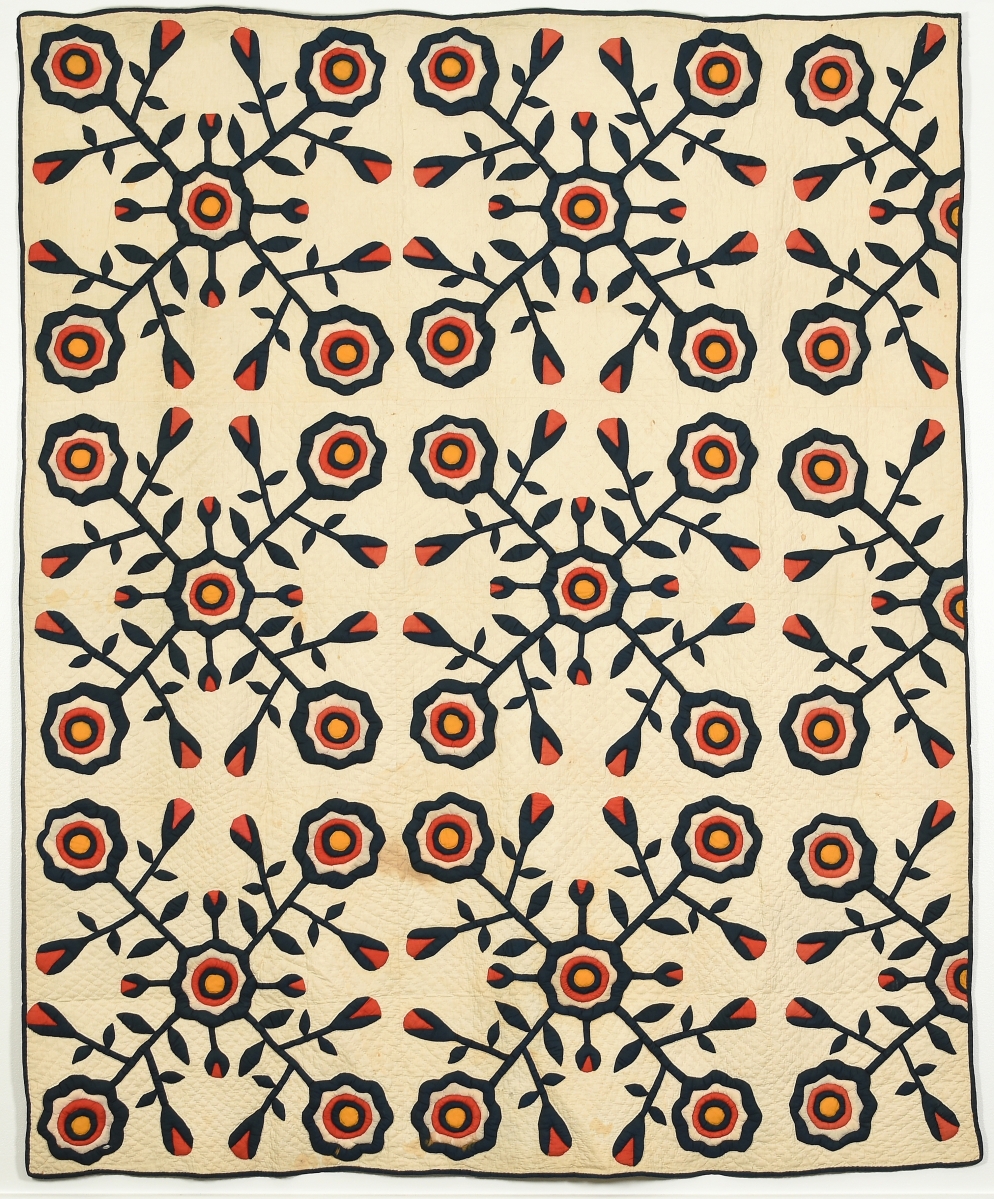

Pomegranate pattern quilt by Isabella (Bell) Phillips Boyd (1862-1953), late 1800s. Cotton, 78½ by 76¼ inches. Gift of Dr Paul M. Goggans.

By Karla Klein Albertson

COLUMBUS, GA. – In history as in archaeology, provenance is all important. This information adds background to the iron tools uncovered in a house foundation or the furniture passed down in an unbroken chain of ownership. Objects bereft of such background – like a canvas by an unknown painter of an unnamed subject – may be pretty but hold limited clues to their secrets.

For those seeking provenance in textiles, the two-stage exhibition “Quilts from the Collection of Paul M. Goggans” – Part I will be up May 8 to December 5 – is the perfect experience, for the maker of each example is well-documented. The stitchers were three closely related women who shared their skills with one another in order to create colorful textiles that combined beauty and utility. Quilting provided these women with a quiet moment of fellowship and fulfillment while pursuing a necessary task.

Over many years, the family kept the collection intact, and when the time was right, Dr Paul Goggans made the decision to donate them to an institution in the heart of the region where the quilters lived and worked. An academic, as his title indicates, Goggans is a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Mississippi, a scientist well aware of the macro and micro patterns of the universe. But when he spoke with Antiques and the Arts Weekly, he wanted to talk about the patterns stored in a closet down the hall from where he slept as a young man.

.jpg)

Installation image, “Quilts From The Goggans Family Of The Chattahoochee Valley.” Part I of the exhibition is on through December 5.

The women who made the 16 quilts in the collection were his great-grandmother, a great-great-aunt, and his own grandmother. He emphasized that although the quilts were beautifully executed, they were made to be used. When the weather turned cold, they came out of the cupboard to keep the beds warm.

One of his personal favorites, on view in the Part I exhibition this year, is the bold Pomegranate pattern quilt, which uses the trapunto technique to achieve texture in the design. By his gift, Paul Goggans hopes to permanently preserve the fragile textiles and allow more scholars and collectors to view them in the future.

When the state of Georgia is in the news today, the focus is always on metropolitan Atlanta, but 100 miles to the southwest lies Columbus, the state’s third largest city, next to Fort Benning. Situated on the Chattahoochee River and the state line shared with Alabama, Columbus was a major industrial city in the Nineteenth Century, sometimes compared to Lowell, Mass., because of its cotton mills.

The family of the quilters lived in the area for more than 150 years, and the quilts in the donated collection span around 70 years, with the seven examples on display in Part I coming from the earlier portion of that time period. These would be the work of sisters-in-law Isabella (Bell) Phillips Boyd (1862-1953), who lived in the Upatoi area of Muscogee County, and Beatrice Virginia Elizabeth Jenkins Phillips (1864-1942), who grew up in Troup County and spent her adult life near Warm Springs in Meriwether County.

Apple quilt by Isabella (Bell) Phillips Boyd (1862-1953), late 1800s. Cotton, 90¾ by 74½ inches. Gift of Dr Paul M. Goggans.

Part II, on display in 2022, will feature quilts by Beatrice Phillips’ daughter Marye Elizabeth Phillips Proctor (1893-1964), who followed in the quilting footsteps of her mother and aunt, while using pastel colors common in the 1930s and 1940s. Proctor was Paul Goggans’ grandmother, and he noted that her life was filled with activity. In addition to years teaching school, she became what was then called a “Home Demonstration Agent,” traveling the state to encourage artistic crafts among women and girls. She left behind her quilts, but her special field of brilliance was in flower arranging.

The Columbus Museum is the perfect home for the Goggans gift because it was founded in 1953 with a dual concentration in American art and regional history, which it stresses in its exhibitions and permanent collection. Discussing the acquisition with Antiques and the Arts Weekly, Rebecca Bush, curator of history, explained that a friend of the museum knew Dr Goggans and had discovered that he had this important family collection. The museum immediately expressed an interest.

“So, these 16 quilts turned up all of a sudden one weekend, and we were very excited to work with them and take a look at them,” the curator said. “Including these examples, we have about 70 quilts in the museum collection, most of those have a regional connection. We have fairly good coverage of time periods and patterns, so we were very pleased to see in the Goggans material several patterns we did not have in our collection before.”

“It was also a great gift to us that there was detailed information on where they were made and who made them – which is often not available – so we were able to do a little bit of a genealogical dive into the family and learn about them that way. The impetus for the exhibit was that it is rare for us to take in a textile collection of this size and especially for all of the pieces to be in such great condition and easily exhibitable.”

Bush continued, “We have large display cases where these are going to be installed, and they are really well-suited to large, three-dimensional objects. So that’s where we can mount these two exhibitions to highlight the new collection of quilts. As you know, quilts are very popular exhibits – and we’ve been in contact with area quilting groups in recent years – so we think that it’s going to be popular with the community.”

The curator emphasized how unusual it was that the quilts had not been dispersed by gift, inheritance or sale: “It should be noted that Mallette Proctor Goggans (1920-2005), the daughter of quilter Mayre Elizabeth Phillips Proctor and the mother of donor Paul Goggans, organized the collection, served as its record keeper, and made quilt images available for publication.”

“They pick up in the late 1870s, early 1880s, when the first of these would have been produced – based on the birthdates of the quilters. The latest ones we have are dated to the mid-1940s. A couple of them are kind of tied to quilting bees or group quilting experiences. They are in really good shape overall, but there are a couple that have stains. These were not art quilts – they were made to be used.”

Triangle Square quilt by Beatrice Virginia Elizabeth Jenkins Phillips (1864-1942), late 1800s. Cotton, 78½ by 70 inches. Gift of Dr Paul M. Goggans.

As far as the stitching is concerned, Bush noted: “The actual quilting techniques that are used vary a little bit from quilt to quilt, and I think that’s where we might see some group quilting as well. This combined individual handiwork with a communal experience. But the patterns are very typical for the time periods in which they were made. These are patterns that these women would have been quite familiar with. The two that are most unusual – and probably my two favorites – are the Apple and the Pomegranate pattern examples, which stand out because they are stitched using the trapunto technique, that gives the fruit a three-dimensional effect.”

Divided into two parts, the Goggans family quilts will be on view over a two-year period. Rebecca Bush said in conclusion: “I hope that people appreciate the skill and craftsmanship of these objects. I hope they see the variety of patterns and colors and fabrics – and the creativity of the makers. I want people to remember that these were objects of household use as well and how the bedcoverings were employed in everyday life. Look at where the fabrics came from – one was made from pieces of a child’s cotton dresses – there are stories behind the materials. Our museum has a dual mission of art and history, so I can appreciate the artistry and the craftsmanship of these quilts, but – above all – they were made to be put on a bed and used by a family.”

The Columbus Museum is at 1251 Wynnton Road. For more information, 706-748-2570 or www.columbusmuseum.com.

.jpg)