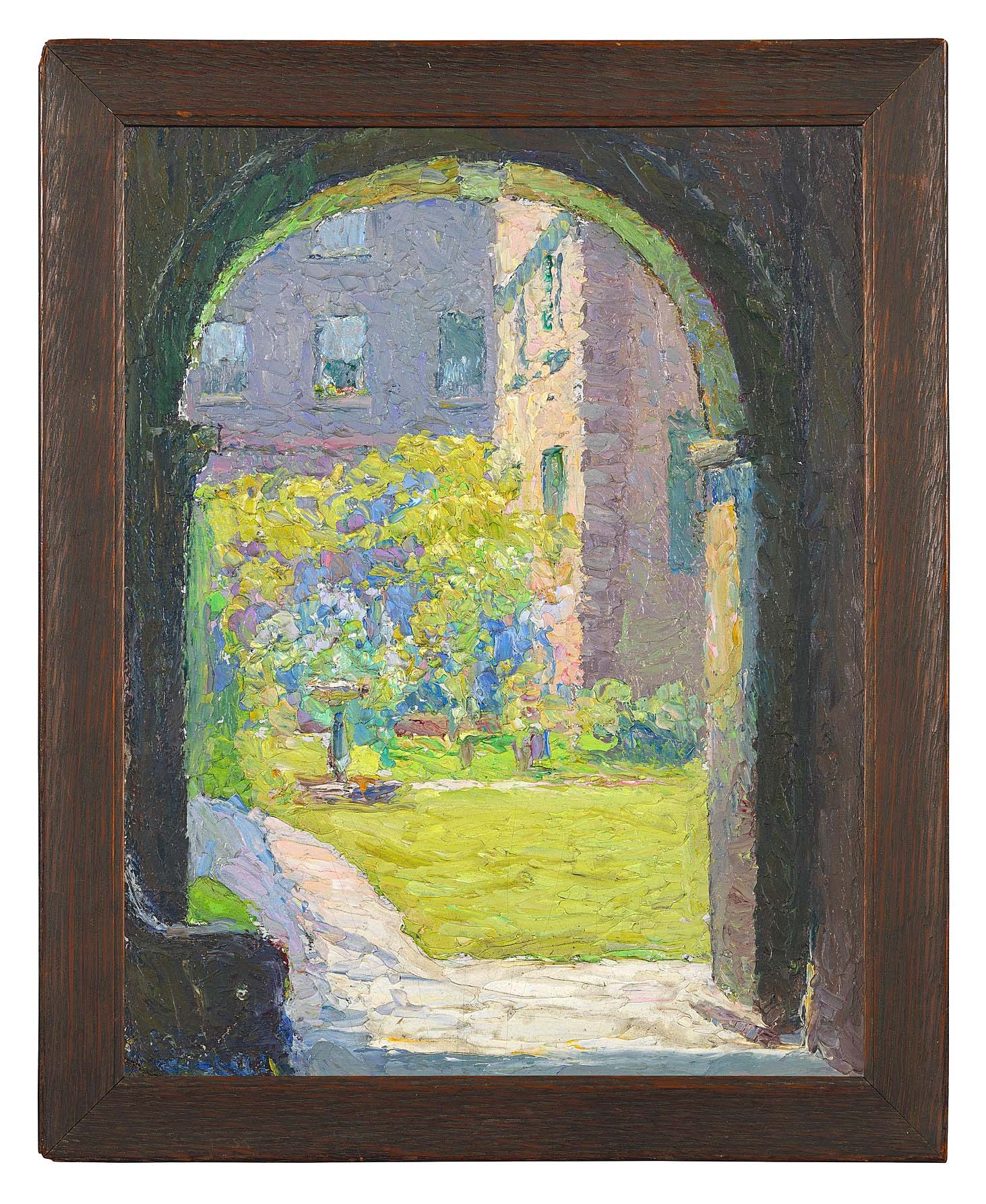

“Hull-House Courtyard” by Enella Benedict (1858-1942), n.d., oil on canvas. Hull-House Collection, 1977.0020.0001. Through an arched entry, a lush interior courtyard at Hull-House offers respite from the busy neighborhood. A white pathway leads to a fountain between two buildings, rendered with visible brushwork in an Impressionist style. The artist Enella Benedict was the founder and long-time director of the Hull-House Art School; she taught drawing, painting and sculpture simultaneously at the settlement and at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She lived and worked at Hull-House for nearly 50 years, the longest resident after Jane Addams.

By Carly Timpson

CHICAGO — In 1889, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr established Hull-House, a utopian residence where diverse immigrants could come together to grow and develop the knowledge and skills necessary to thrive in their new home of Chicago. As the first settlement house in the United States, Hull-House was more than just a place for people to learn — the institution quite literally crafted community and became an integral part of Chicago’s Near West Side neighborhood.

Liesl Olson, Jane Addams Hull-House Museum director, shared, “Hull-House was a social experiment — a new way to live, to work, to love. It was a place for college-educated women immigrants, and they all rejected social standards to live with each other and help the poor.” In time, Hull-House emerged as a vibrant hub of progressive ideas and unconventional lifestyles, where educators saw the arts as a means for social change within the immigrant communities of the Near West Side.

To celebrate the history of arts education at Hull-House, the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) presents “Radical Craft: Arts Education at Hull-House, 1889-1935,” an exhibition of work by early Twentieth Century immigrant artisans, many of whom were overlooked and their identities were lost to time. Works by better-known Hull-House artisans, such as Alice Kellogg Tyler, are on display in companionship with those whose makers may no longer be remembered.

Jane Addams holding a textile between a loom and spinning wheel, possibly at an exhibition of the Labor Museum, Women’s World’s Fair, Chicago, 1927. Chicago Daily News Photograph Collection, Chicago History Museum, DN-0084134.

Olson noted, “Hull-House was founded with the belief that the practice of the arts is fundamental to what it means to be human, and this exhibition embodies that belief by uplifting the underrecognized artistry and experiences of immigrants who taught, learned and practiced here.”

It has been more than six years since the last major exhibition opened at the museum, and, according to Olson, “Radical Craft” was prompted by the questions of “Why, in 1889 when Starr and Addams moved to the Westside of Chicago, why was the first building they built an art gallery?” and “How did that serve the most neglected and impoverished communities in Chicago?”

In researching these questions and delving into the Hull-House archives, Olson and other curators “found that the experience of art, both looking and practicing, were fundamental to their ideas of democracy and their values about what it means to be human. They put the arts at the center of all their projects for social reform.”

Hull-House co-founder Ellen Gates Starr (1859-1940) was the one who, according to Olson, “really brought the principals of the Arts and Crafts movement from the UK. Slowing down, doing something with your hands, the values and labor of doing something not focused on mass production, et cetera. She was already lecturing on arts education before she and Addams founded Hull-House and she’s the one who brought Jane Addams to Chicago.”

Ellen Gates Starr under arrest during the Henrici restaurant waitress strike, 1914. Chicago Daily News Photograph Collection, Chicago History Museum. DN-0062288.

Originally, the exhibition was to be focused on the social reformers like Addams and Starr and the other Hull-House residents like Tyler. However, after uncovering more history and artifacts from the collection, Olson suggested flipping it to celebrate the unknown or once-known makers too. She shared, “In attempt to recover their stories, we went through all of the yearbooks and newsletters that Hull-House produced. Most are upper class, but every once in a while, we’d come across the immigrants. We culled all of these names and the craft at which they excelled, and the names are on the walls throughout the exhibit as a tribute to all of the people whose experiences were vital to Hull-House and the craft. Ultimately, we cannot tie each piece back to a maker, but we display it anyway and we engaged a present-day artist to help us mount it very beautifully.”

Alice Kellogg Tyler, one of the better-known artists from Hull-House is highlighted in the exhibit and was part of the original framework for the show. Olson shared, “One of the rooms is entirely dedicated to her. You’ll never see more of her paintings anywhere than at Hull-House. Her painting ‘The Mother’ was shown at the Chicago World Fair and she did a lot of portraits of the social reformers at Hull-House.” Visitors to the exhibition will be able to view “The Mother,” a portrait in which the primary subject, a peasant woman, has just finished nursing her baby. This work, which seems so contrasting to the unconventional, progressive ideals at Hull-House, was one of Olson’s influences in digging deeper for the exhibition. She shared, “It is so extraordinary not only because it’s so virtuosic in its attention and color and figural expression but also because it was given to Hull-House from Alice Kellogg Tyler and hung over the fireplace. I question why this traditional painting was at the center of such a non-traditional place where women were rejecting the norms and expectations of womanhood. Addams was giving visibility to women and their power. It’s so beautiful in its complexity and history and as an aesthetic work.”

“The Mother” by Alice Kellogg Tyler (1862-1900), 1889, oil on canvas. Hull-House Collection.

Furthermore, in researching for the exhibition, Olson discovered that Kellogg Tyler may have done a portrait of Ida B. Wells. It is known that Wells knew Addams, so it is possible that the connection led to Kellogg Tyler’s portrait. Olson, speaking of the portrait, said, “We don’t know where it is, and I want to track it down. It gets at that larger question of how open to the Black community was Hull-House? We know it was always integrated, Mexican Americans, Italian Americans and a few Black Americans but very small in number. How much of an effort did Hull-House make to serve the African American community during the great migration? There’s more work to be done to learn about this.”

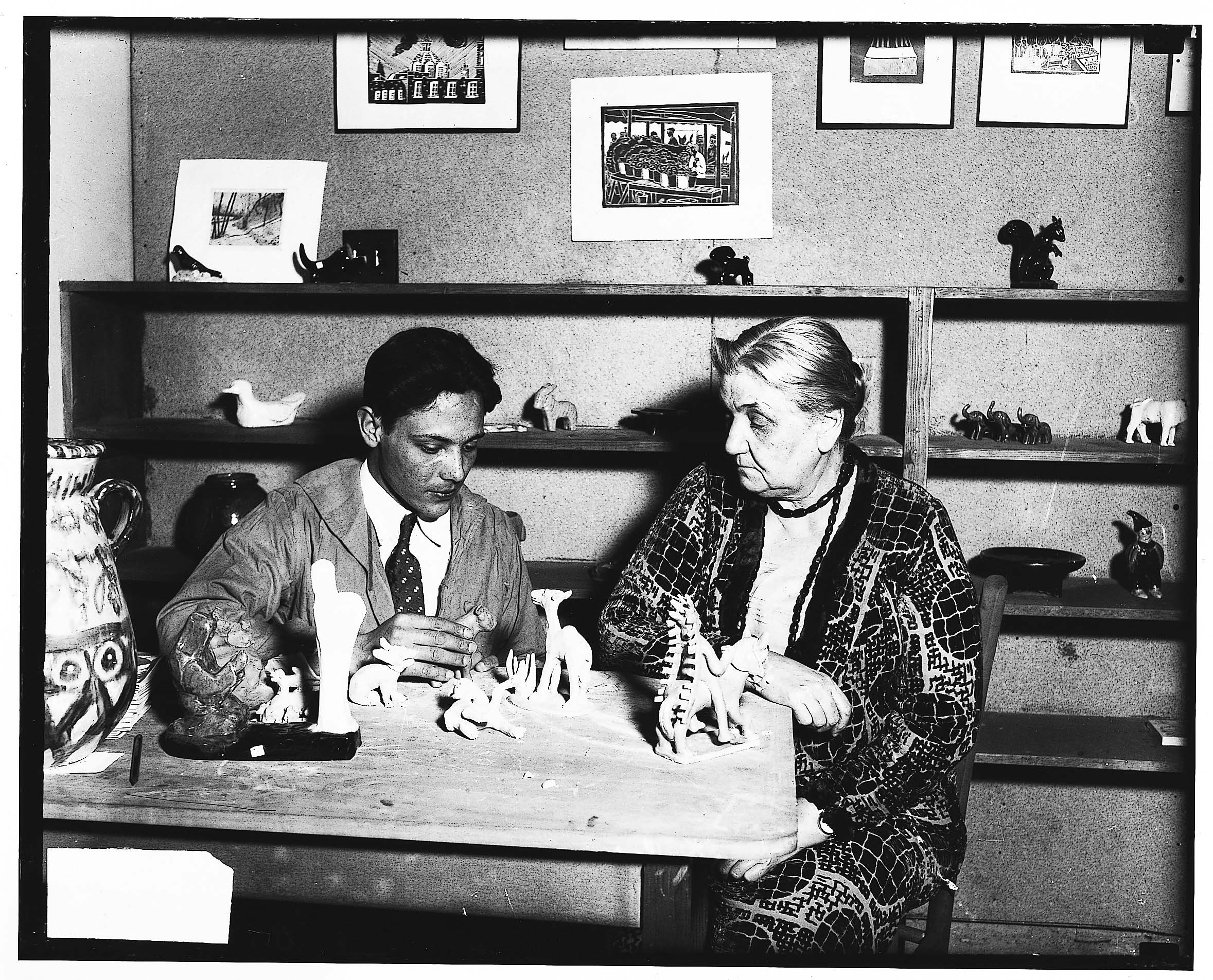

Lesser-known artists, such as many of the ceramicists who worked with the Hull-House kilns or those who crafted intricate textiles, are honored throughout the exhibition whether or not they were able to be identified. In the section relating to the Hull-House Kilns, visitors will see ceramics by Jesús Torres alongside works by Hilarion Tinoco, José Ruíz, Miguel Juárez and others who have been forgotten to time.

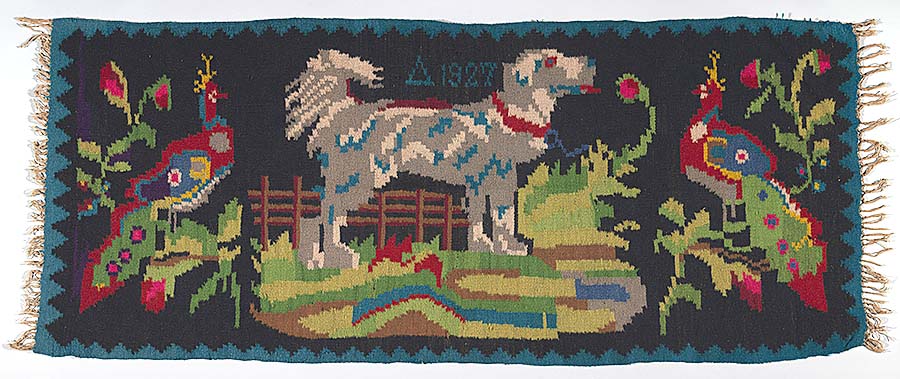

The Labor Museum section presents the textile collection, which, according to Olson, “was a huge revelation.” She commented, “There is so much variety and beauty, but we hadn’t really looked at it much even though it lived for a long time in the museum’s attic and basement. Only about half of the textile collection is on view. It is extremely varied, in both style and expertise.”

Floral decorative plate by Jesús Torres (1898-1948), circa 1927-37, ceramic. Hull-House Collection, 1970.0043.0002.

“We’ve had conservators come look at the collection and help us understand it. It’s about 70 pieces coming from the turn of the century around 1910, made by many immigrant women who came to Hull-House to demonstrate their heritage and craft, who showed their old world to the new. We don’t have a lot of provenance or information about the makers. One of the real risks we took in this exhibition is deciding to show it anyway in order to elevate the work of unknown artisans and treat it the same alongside the works of better-known artists”

One notable work from that collection is a long woolen tapestry, made in 1927 by a maker named Eugenia Parry. Parry is known to the museum through records of her being in the neighborhood and this work was donated by a family member in 1977. Others include doilies, mats, rugs and table runners, which are unattributed and undated, but known to have been created by the communities surrounding Hull-House in the early Twentieth Century.

In some instances, the maker was not initially known to the curators, but research in the Hull-House collections and records helped change that. Olson tells of one such story, “We were able to unite maker and object — a copper pitcher and a bowl that were made by a Russian coppersmith named Falick Novick. We have a picture of him, his wife and his son standing in the shop they opened in the neighborhood where he designed and sold these handmade copper and silver pieces. He worked in metal and enamel in Hull-House. He arrived in Chicago in 1907. They’re really well-used but they look nice with the picture.”

Copper pitcher by Falick Novick (1878-1957), n.d. Hull-House Collection, 1994.0007.0007.

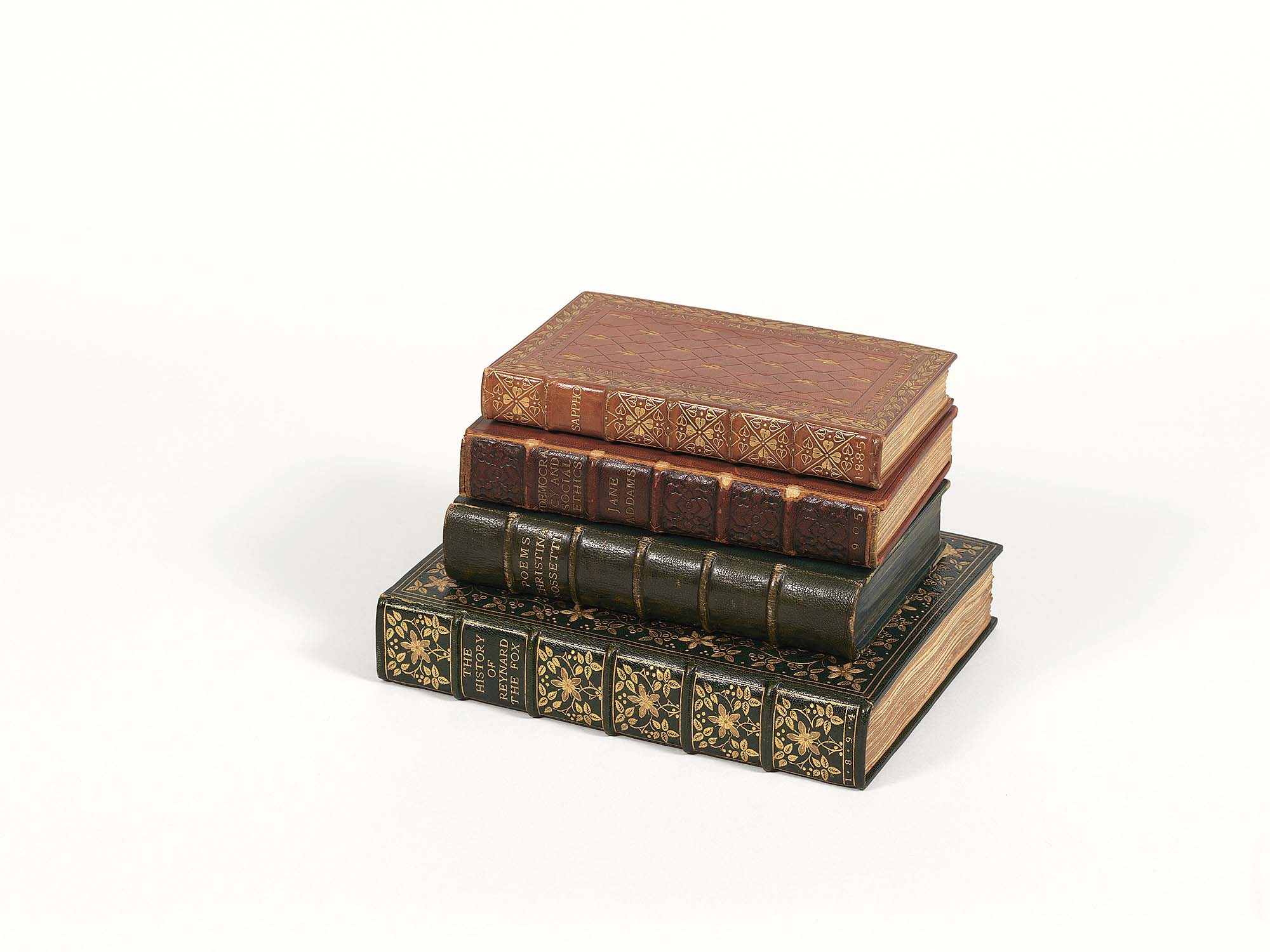

Despite Starr being one of the settlement’s co-founders, the museum had never before “taken her on” as a curatorial subject. According to Olson, [Starr] “launched this ‘delusional’ project to start a book bindery at Hull-House where she could slow down and do something with her hands. It was laborious and costly, but she produced stunning books, and we have 4 or 5 of them on display in the exhibition. These include works by Addams (Democracy and Social Ethics); the Greek poet Sappho, which was gifted between one reformer to another, a gift between women outside the expectations of capitalistic society; and others (poems by Christina Rossetti).”

In addition to individual makers and their craft, the exhibition also highlights lineage and community. One such example is “Cottage Grove,” a painting of three African American streetcar riders sitting together, by Morris Topchevsky. In exhibiting this work alongside others, Olson says the Hull-House Museum is “highlighting lineage, as Morris Topchevsky studied with Enella Benedict, who was director of the Hull-House Art School. Topchevsky taught artists like Margaret Burroughs and Charles White, who taught artists and educators who are active in Chicago today. We are flagging a lineage of arts education in the city. It’s a moment to think about how that really began at Hull-House. It ties into this idea of what it means to be heard and seen and to live in a democracy where arts aren’t just this ‘extra’ — they’re fundamental to the experience of what you’re capable of as an individual.”

“The Mother” above the fireplace in the southeast parlor at Hull-House, circa 1910. Hull-House Photograph Collection, 0000.0158.0610.

Reflecting on the exhibition and its timeliness, Olson remarked, “Hull-House is a site of conscience. In these walls live the history of trauma — migration to a new urban center from places across Europe. We are always keen to tell those stories of what remains even through the experiences of displacement, loss and removal and celebrate the creativity that is a resistance to the way the world works, to capitalism. It’s moving, it’s beautiful, it’s a tribute to so many different new and old migrant communities. Hull-House is a place where so many of these various communities could come together and enjoy the arts.”

In visiting the exhibition and learning about Hull-House’s history as well as that of these makers, Olson hopes that visitors leave with an increased knowledge and understanding of craft’s larger purpose — “the power of an aesthetic experience to make you feel the worth and value of your life and other lives. We hope people are inspired to do something with their hands. I’m not a sewer or painter but I do love to cook and that is certainly part of the Labor Museum. The desire to do something with your hands can be very oppositional to all the forces that tell us to move quickly and develop products. Something you can do that is a different mode of attention, there’s value in that.”

The Hull-House Museum has partnered with community organizations Red Line Services and Firebird Community Arts to present a series of programming for local migrant communities and those who are experiencing houselessness. These will include a meal, an art demonstration and an invitation for participants to make something for themselves. In addition, there will be Radical Mending Workshops, “which are for people like me who don’t know how to sew or do these craft things. These are in partnership with The Waste Shed, an organization that repurposes craft fabric and things that can be used for art. They’ll let people bring things in and learn to mend them,” said Olson. Information about these programs can be found on the museum’s website.

“Radical Craft: Arts Education at Hull-House, 1889-1935” is on view through July 27. The Jane Addams Hull-House Museum at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) is at 800 South Halsted Street. For information, www.hullhousemuseum.org or 312-413-5353.