Setting an auction record for any work by Tiffany Studios, this Dandelion lamp sold for $3,750,000 to an agent. It was created for Paris’ Exposition Universelle in 1900 and would also go on exhibit at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, N.Y. The lamp was a discovery, its whereabouts unknown since its manufacture. It had been sitting in a Virginia home for at least 70 years. David Rago said, “It was a masterpiece… It was just a gem of American Art Nouveau by a master craftsman at a master studio.”

Review by Greg Smith, Photos Courtesy Rago Auctions

LAMBERTVILLE, N.J. – It took a half second for auctioneer David Rago to point to his favorite lot in Rago Auctions’ May 13-14 sale. “The Tiffany lamp,” he said, “not just because of what it brought, but because it was a masterpiece. It showed the pinnacle of American craft at that time. It covered all the bases: international show, national show, disappeared, great craftsmanship.”

The Tiffany Studios Dandelion lamp, one of only three known to have ever been produced by the firm, broke an auction record for the maker when it sold for $3,745,000 to an agent (see Antiques and The Arts Weekly, issue May 28, 2021).

As Rago alluded, the fresh-to-the-market lamp featured a story that whips up a perfect storm scenario among buyers. Presumably designed by Clara Driscoll in 1900, the lamp was Tiffany’s representative at the Exposition Universelle in Paris that year. Not long after in 1901, he strutted it at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, N.Y. The trail runs cold for about 50 years until a Virginia family with diplomatic ties assumes ownership and it remained in that family ever since, surfacing only two months ago.

The second highest lot in the sale, and the highest for any ceramic work, was Peter Voulkos’ untitled (Stack) that brought $400,000. It was created in the same year that Voulkos and John Mason created a walk-in kiln, which would prove instrumental in the making of monumental works, like this example measuring 65 inches high.

“The main thing was that it was a great piece of hand-wrought American Art Nouveau,” Rago said. “The Tiffany you see is largely cast with repeated patterns. If you look at a Wisteria lamp, it’s a Wisteria lamp. But this one here, someone banged out a flat sheet of copper with repoussé and chased it. It was just a gem of American Art Nouveau by a master craftsman at a master studio.”

The entire sale would gross more than $10 million for Rago as it produced a number of notable results.

Selling for $312,500 was an early Sculpture Front cabinet by Paul Evans. The firm spoke with fabricator Dorsey Reading who related it was one of the first three, if not the first, Sculpture Front cabinets ever made. The Sculpture Fronts are considered to be among the finest and most artful designs Evans ever created.

“I asked Reading, ‘how do you know it’s one of the early ones?'” Rago recalled. “He pointed to the nails that are holding the metal to the carcass and said they were hammered by hand. The first three were made that way and then they fine-tuned the process and nail guns were used. The gauge of the carcass was a thicker gauge than they used later, and they didn’t use the same hinges later on, either. This one took two weeks to make. By the time they fine-tuned the process, they could make them in a week.”

Among the first Sculpture Front cabinets ever made by Paul Evans, this example brought $312,500. With these earliest examples, it took the fabricators at least two weeks to complete a single unit. When they got the process down, it took only one. It had provenance to America House, the first retailer of Evans’ Sculpture Front works.

Rago noted the cabinet had provenance to America House, an early craft gallery in New York City that had retailed the first piece of Evans’ Sculpture Front works, a screen.

“Only about 75 Sculpture Front pieces were ever made,” Rago said. “These early one-off pieces were fabricated on the spot with Dorsey and one other fabricator, with Evans walking through and saying, ‘Let’s do this’ with a drawing on a napkin. Evans studied jewelry design at Cranbrook, he was a working metalsmith until the 60s, you can see that aspect in these early forged elements.”

Selling for $87,500 was a Paul Evans custom torch-cut, welded and enameled steel chandelier made for Martin Brooks of Doylestown, Penn. The auctioneer noted the firm had offered a wall sconce in the past in this design, but this was the first Evans chandelier they had ever sold. After the sale concluded, a second example came out of the woodwork, making at least two known.

In a catalog essay introducing the Brooks collection, the firm wrote, “Brooks first met Phil Powell around 1955 at the Philadelphia Convention Center, where Powell was selling DIY furniture sets. The two quickly struck up a friendship. Brooks loved Powell’s furniture, and Powell needed landscape work done, so they came to a mutually beneficial agreement. As Brooks recalls, ‘Phil designed my house and the furniture, and I did his gardening, mowed his lawn, and even put in a waterfall.’ They became close friends and Brooks often supplied Powell with wood that he found during his landscaping jobs. It was through Powell that he met Paul Evans – ‘I met Paul through Phil. I always had a cigar, and Paul always had a cigarette’ – with whom he struck up a similar arrangement: in exchange for landscaping, Evans designed furniture for his home.”

“Two people had the right space for it,” David Rago said about the $131,250 result for this George Nakashima Frenchman’s Cove II extension dining table.

Also from Brooks’ collection was a circa 1960 enameled iron, walnut, gold leaf and slate-top Loop coffee table that sold for $25,000, a collaboration between Powell and Evans. In the same vein was a custom storage unit that brought together both of their styles with torch-cut faced cabinets on top (Evans) and a lower cabinet featuring a gold-leaf design (Powell). It also sold for $25,000.

From the other New Hope craftsman, George Nakashima, was a $131,250 result for a Frenchman’s Cove II extension dining table. Crafted in American black walnut and rosewood, the table was made in 1961 and had provenance back to Nakashima. It handily surpassed the $20,000 high estimate, Rago saying that two bidders just wanted it. Not far behind at $106,250 was a set of eight Conoid chairs by Nakashima, circa 1973, in American black walnut and hickory. A Conoid bench would take $75,000, while a special single pedestal desk sold for $68,750.

Ceramics were led by a $400,000 result for a 65-inch-high untitled (Stack) work by Peter Voulkos. It was hand-built from stoneware with oxide and/or slip glazes in 1957, the same year Voulkos and John Mason created a studio with a walk-in kiln.

Reaching back the furthest was a 4-gallon jar by enslaved potter Dave Drake, made in 1855, that brought $68,750. The 14-inch-high jar featured a dipped alkaline glaze and was completed at the Lewis Miles Pottery.

“We felt Drake had a certain symmetry with Ohr and the Kirkpatricks, even though he was obviously potting from a very different and difficult place,” Rago said. “Still, there is modernity in a slave who was taught to write, taught a craft, and his work spoke to me as a presage to the century that would represent awareness of Black (well, non-white in general) rights.”

A number of tiles dating to the early Twentieth Century would produce outstanding results. Selling for $81,250 was a set of two “The Pines” tiles by Addison LeBoutillier for the Grueby Faience Company. Together, they measured 14 by 26¼ inches. The pair came out of a house in Massachusetts and were new to the market.

“These represent an iconic image of American Arts and Crafts of the highest order,” Rago said. “They were used for the cover of the Princeton Arts and Crafts exhibition in the early 1970s, that was the show that kicked off the Arts and Crafts revival. They are by Grueby which, in many ways, was the central pottery of the movement. Further, these are rare – I have had a set of them only once before in nearly 50 years.”

Over doubling estimate was a Tiffany Studios Poppy table lamp that sold for $93,750. The shade sits on a bronze “mushroom” library base.

Not far behind was a $75,000 result for a singular Wisteria tile by Adelaide Robineau, circa 1910, 8½ inches square. Rago noted that this tile was originally intended to be installed in the artist’s fireplace in her home in Syracuse, N.Y. She took inspiration from the wisteria vines in her gardens.

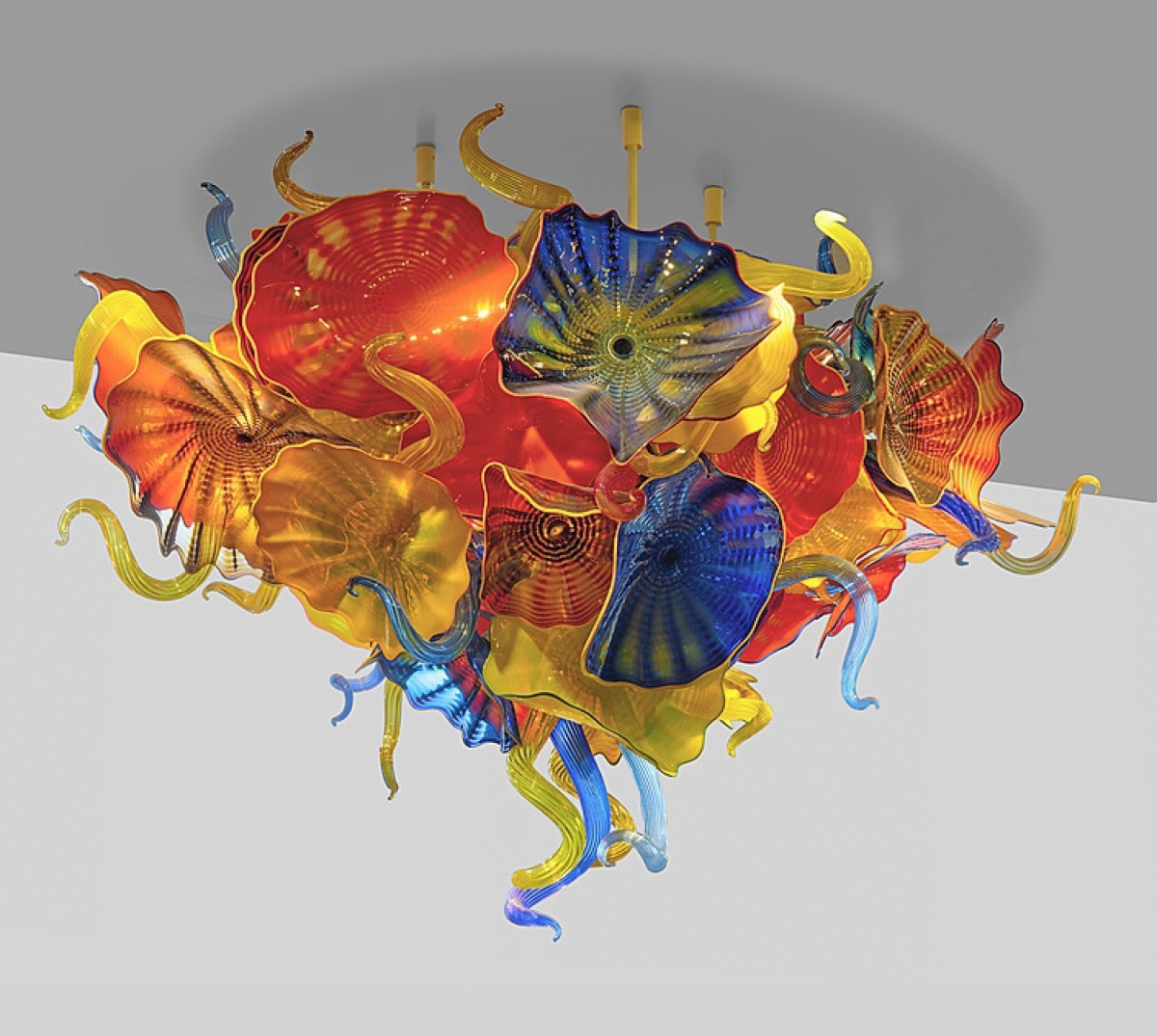

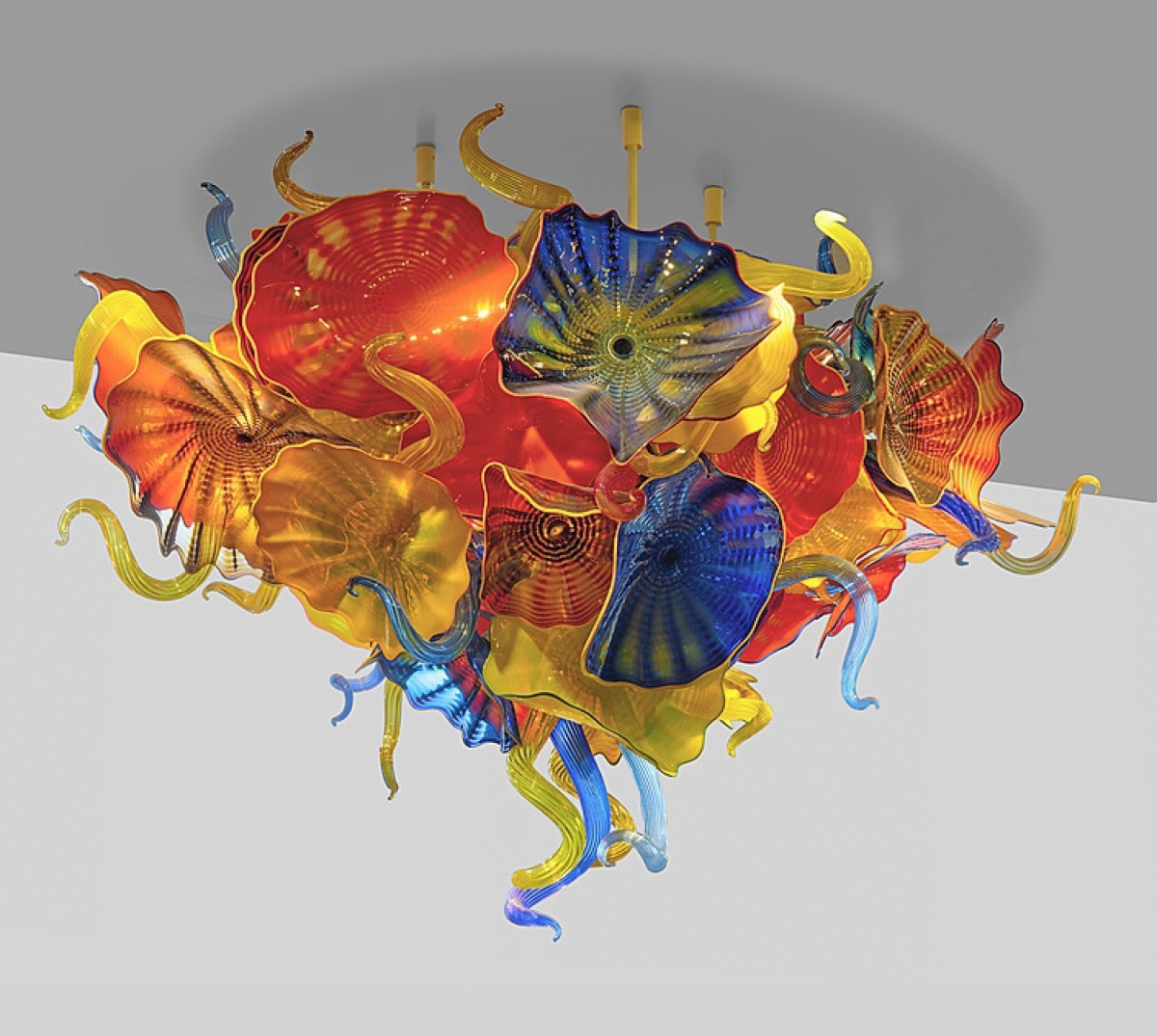

Glass found its leader in a Persian and Horn chandelier by Dale Chihuly, which sold for $125,000. It measured 67 inches across and belonged to a New York collection after its purchase from the artist in 2006. From the same year was a cast glass sculpture, “Semi-Reclining Dress Impression,” 41 inches tall, by Karen Lamonte, that sold for $62,500.

Overall, the two-day sale went 268 percent sold by value and 89 percent sold by lot. All prices include buyer’s premium. For information, www.ragoarts.com or 609-397-9374.