Attributed to Nineteenth Century Evans, N.Y., carver Asa Ames, this 43-inch-tall figure was the top lot of the day at $53,125, selling to New York City dealer Joshua Lowenfels. The work had been discovered about 20 years ago in Buffalo, N.Y. The American Folk Art Museum put on an Ames exhibition in 2008 and his known works number between ten and 20.

Review and Onsite Photos by Greg Smith

LAMBERTVILLE, N.J. – There is an archetype in storytelling. A normal, everyday character transcends the common world – the place you and I and everyone else lives in – to wake in a fantasy reality rich with new experience and a whole different rulebook, often including new laws of physics. Think Dorothy with Kansas, Harry Potter and the Muggle world, and now, please, turn your attention to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

After diving into a rabbit hole, drinking from a bottle and physically shrinking to the size of a mouse, Alice finds herself following the directive of an ambiguous placard as she eats a cake in hopes of returning to her prior height, to little immediate effect: “She was quite surprised to find that she remained the same size: to be sure, this generally happens when one eats cake, but Alice had got so much into the way of expecting nothing but out-of-the-way things to happen, that it seemed quite dull and stupid for life to go on in the common way.” The chapter ends and the following one begins with Alice crying the name of Rago’s December 1 sale as the cake kicked in and she grew to 9 feet tall, “Curiouser and curiouser!”

Out-of-the-way things made in an otherwise common world characterized Rago’s Curiouser and Curiouser sale of Outsider, fine and folk art, curiosities and objects. So wild were the offerings that it made general sales and normal life, as Carroll put it, seem quite dull. After its 2017 debut, the sale again returned with New York City dealer and curator Marion Harris as specialist in charge of a collection of art and objects that have transcendent qualities to other realities: phrenology objects, massive insects, trade figures, circus material, specimens, Visionary and Southern folk art, carved figures and animals, illustrations, posters and more.

“These are alternative categories from what you usually see,” explained Marion Harris. “Collectors of outsider art are almost like the outsider artists themselves. There’s a parallel there. They want to put themselves into a different category than other collectors. They want to break the rules. They want to create a look that is outside of the mainstream.”

In total, the 370-lot sale grossed $493,756 for its 70 consignors. Bidding interest was plied by more than 500 online bidders, 142 phone bidders and 64 absentee bidders, with approximately 30 percent of the property selling online by value, largely to left bids, and almost 50 percent selling by phone.

The top lot of the sale came from a 43-inch-tall pine figure attributed to Nineteenth Century Evans, N.Y., carver Asa Ames. The figure sold for $53,125 to New York City dealer Joshua Lowenfels. The work, which had previously been offered privately by both Frank Maresca and Lowenfels, was featured in Maresca and Roger Ricco’s 2002 American Vernacular. Having died of Tuberculosis in 1851 at only 27 years old, four years after he began carving, Ames’ work is limited in number to between ten and 20 known examples. The American Folk Art Museum put on an Ames exhibition in 2008.

Jon Serl’s 48-inch-square oil on Formica “Serl’s Headstone” was the California outsider artist’s top lot, selling for $20,000. It tied an auction record for Serl set by Sotheby’s in October 2018, and built off the 2017 Curiouser sale when Rago set the artist’s auction record at $10,625. That is three new artist records in the span of one year and three months. Specialist in charge Marion Harris said, “No one has really collected him like this before and prices have never reached this level.

“It has a very determined look,” Harris said. A daguerreotype of Ames in the collection of the American Folk Art Museum is the artist’s only known picture. As Harris motioned to a printed copy of the image, she said, “And what’s more is that this work looks similar to the carver himself.” And he did, particularly with his inset eyes. Harris said that a proper authentication is in the works, but she is confident in the hand.

Building off strong interest in last year’s sale, works from Twentieth Century Californian outsider Jon Serl performed strongly, with a 48-inch-square oil on Formica, “Serl’s Headstone,” tying an artist auction record at $20,000. Rago had previously set the record for the artist in the 2017 Curiouser sale, before Sotheby’s sold a work in October, 2018, for $20,000. The piece sold to a phone bidder. Serl, real name: Josef Searls, dedicated himself to painting in his 1950s, though he refused to show his work in a gallery for 20 years. His first exhibition was mounted in 1970 when he was 76 years old. The sale featured four other Serl works and all sold, including his 1969 “Hoop Dancer” for $9,375. Serl was no doubt familiar with the character pictured in the work, having been raised in a vaudeville theatrical family in his youth. Following behind was an untitled work featuring eight figures in green for $7,500, “Leaving for the Army” at $5,000 and “Lady with the Garden Flax” for $4,375.

“He’s coming onto the market fairly unexpectedly,” explained Harris. “Not many of his works have come on, so there’s an element of surprise – the theatricality of it appeals to buyers. These collectors like to forge their own identity with artists and they can do that with Jon Serl. No one has really collected him like this before and prices have never reached this level. When outsider collectors find something away from the mainstream that they can identify with, and not everyone knows about it yet, then they go for it.”

Twentieth Century Southern folk art did well, with names like Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Purvis Young, Howard Finster and Eddie Arning bringing solid results. Young’s top lot came in the form of an untitled mixed media on board featuring soldiers, which sold for $5,313. Perhaps more intriguing were five lots of the artist’s notebooks featuring pages of painted works as well as found materials. These were from the collection of the well-known Georgia collector/dealer Jimmy Hedges, who died in 2014. Through The Hedges Family Charitable Foundation, his collection is being dispersed by his son Jim Hedges V to institutions like the Smithsonian and through auctions. While two of the lots passed, the other three sold for $2,750, $2,000 and $1,875. Sudduth was a more affordable choice for buyers, with his seven lots in the sale topping out at $938 with a 24-inch-square mud and paint on board of a rooster. Finster’s four works in the sale were all manageable, the tallest being a 27¾-inch-high Santa Claus, which sold for $938. Arning’s lone painting, the 25-by-29-inch pastel on paper untitled work of two men and a dog, went square between the estimates at $2,750.

Buyers found themselves stepping right up for the carnival and circus material on offer. A sign for a sideshow led this category promoting a living calf with three eyes, underjaws, tongues, sets of teeth and double nostrils. All for only 10 cents then and $3,125 now. A Twentieth Century painted sheet iron elephant shooting target mounted to a stand was a nice form and it fetched $2,000. Attributed to the Brooklyn, N.Y., Stein & Goldstein company was an unpainted carousel horse, which was a nice buy at $1,250. Two French painted passe boule games sold, bidders preferring the dog at $1,000 to the clown at $625.

Before the sale got underway, Harris mentioned that the automatons had been receiving a lot of interest. Sure enough, at $18,750 was a rare Nineteenth Century French automaton, the fourth highest lot in the sale. This automaton featured a clown nailing a wooden crate shut when suddenly an African American delivery man springs the lid open in an attempt to escape before the clown slams the lid back down and a rat scurries out from a hole in the crate. Many of these works, automaton expert Jere Ryder explained before the sale, were social commentaries of their time. Ryder is the curator of the Murtogh D. Guinness Collection at the Morris Museum.

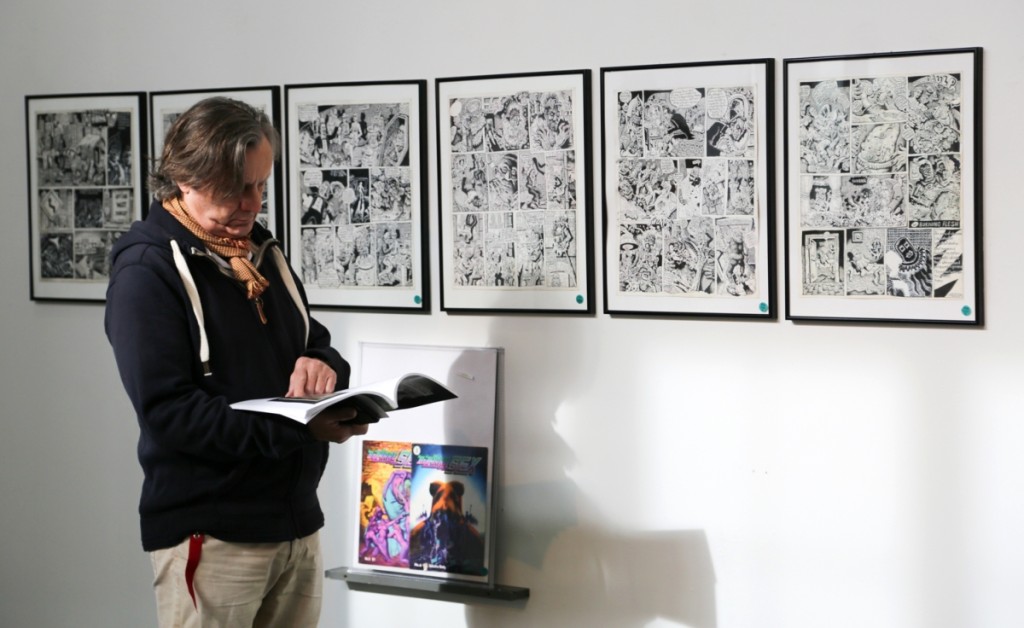

A previewer stands in front of the complete set of six original broadsheet artworks for Joe Coleman’s first published graphic story, Highay, which was published by Kitchen Sink Press in its underground comic Bizarre Sex 1977 #6. It sold just under the low estimate at $17,500.

Wooden articulated figures, ranging from life-size examples on down, proved themselves worthy among the sale’s other offerings. A late Nineteenth Century life-size artist’s mannequin, cataloged as possibly Italian, sold for $12,500. Behind was a walnut horse from France, 24 inches long, which sold for $9,375. A more economic choice was found in a 71-inch-high male figure that, while carved more primitively than the others, found a buyer at $2,125. At the same price was a finely carved French example from the Nineteenth Century, only 7 inches tall.

This sale provided for the market debut of Twentieth Century American self-taught artist Daniel Rohrig and his superbly-rendered works on paper featuring Asian cinema subjects. Rohrig served in World War II in the Pacific and became fascinated with the art of Asian movie posters, drawing inspiration from them while placing some of Japan’s most famous actors into his works. Four of the artist’s six lots, all mixed media on paper, found new homes, the top untitled lot bringing $1,188. Two were purchased by the American Folk Art Museum for its permanent collection.

Titled “Waste,” a 1990 work from contemporary glass artist Judith Schaechter found the second highest result in the sale at $21,250. The work had been exhibited at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery and two shows with the Helander Gallery. In the form of a light box with pieced etched stained glass, the 17-by-17-inch work featured a man naked from the waist down wearing only a jester’s tunic and cap crouched in a pile of garbage as he eats off a plate. The artist remarked that the work is a comment on humankind’s pollution of the environment.

The complete set of six original broadsheet artworks for Joe Coleman’s first published graphic story, Highay, published by Kitchen Sink Press in its underground comic Bizarre Sex 1977 #6, sold just under the low estimate at $17,500. Four works from American artist Sarah Seaver all found buyers. Seaver is a partner at the Jaffrey, N.H., Seaver & McLellan antiques firm. Her work focuses on allegorical assemblages of taboo materials like medical specimens, bones and insects that often employ humor. At the top was a 2018 work “Go Wash Your Bowl,” which sold for $1,625.

Many of the curiosities in the sale elicited the same progressive response: an eyebrow raise to further inspection to amusement. These included a taxidermy of a prize-winning Cocker Spaniel, $1,750; a collection of glass eyes, $2,000; a carved marble headstone for the horse Gay Pete, $1,750; a pair of orange woolly cowboy chaps, $563; and a group of eight naked dolls in an antique painted wagon, $313. Although they passed, a few lots were intriguing enough to merit mention: an incised phrenological human skull, an 1890s albumen print of eight cadavers standing around a table with their arms around each other and two large castings of beetles from a German natural history exhibition.

A number of folk art pieces also deserve mention, including a heavily carved American walking stick with images of men, monkeys, snakes and birds, which went out at $11,250. An encrypted political folk art crossword puzzle fan proved a winner as it brought $10,000. Harris sent an image of the work to New York Times crossword editor Will Shortz, who said that this was likely for a 1930s puzzle contest where the public was encouraged to submit their own elaborate crossword puzzles. Shortz mentioned that he owned two works from the contest. And what better way to ring in the new year with a 64-inch-high tramp art clocktower, which sold at $3,750.

In the broad picture, Harris and Rago partner Miriam Tucker were pleased to bring this sale to the market but were disheartened with its commercial performance.

In a release, they jointly said, “The critical response was brilliant. The commercial response was disappointing, with little of the bidding pressure expected on the day of sale, despite a robust marketing campaign.”

Despite the sale’s totals, the firm is committed to offering this sale in the future. “Though the auction gods of 2018 have spoken, Rago has enormous faith in the potential of this market in 2019 and beyond. Outsider art is gaining in value and appreciation and Curiouser attracts the most diverse audience of all our sales.”

All prices reported include appropriate buyer’s premium. For information, 609-397-9374 or www.ragoarts.com.