Article And Photos By David Killen

NEW YORK CITY — As far back as I could remember, I always got up on weekends and went to the flea market in New York City.

At first it was because I needed the money, and then later it was for the fun, the joy of the hunt, and I began to run into other flea market regulars, who had become part-time partners in the search for buried treasure.

The year was 1982. I had just graduated college, and at that time Manhattan was an antique hunter’s dream.

There were countless flea markets, thrift stores, antique shops, antique shows, street fairs and even rummage sales in church yards, to keep the wandering eye occupied.

The former Chelsea Antiques building has become a residential condominium, except for the auction house on the first floor.

The biggest and baddest area for antiquing was Sixth Avenue and 25th Street, the heart of the flea market world in New York. There were easily five large open lots of sellers in a three-block area along with indoor markets, antique shops, junk stores and antique malls.

The first time I walked onto what was called the “main lot” on 25th and Sixth, I went up to a man selling a pair of silver candlesticks and asked the price. “2500,” he said without blinking. I nearly passed out. I had never heard of prices like that at a flea market.

I turned around and ran back uptown, to the local flea markets on the Upper East and West Side where prices were comfortably in the $5 to $10 range.

It took me years to brave another trip down to the “main lot,” where I slowly began to realize that the $2,500 price was often next to a $10 price and a $10,000 price. There were no rules.

I was proud when the day came that I found a silver centerpiece on the main lot and paid $2,500, selling it later that day for $6,000 to a private collector. I had “arrived.”

But as the years went by and the real estate changed in the area, dealers began to notice the flea markets disappearing.

It starting with the “free lot,” a large sprawling flea market across the street from the main lot. One day it closed down, and overnight it seemed like a 50-story luxury apartment building sprouted up.

One by one, the open air parking lots that housed the flea markets on the weekends were sold to developers, turning the dilapidated area from a neighborhood that primarily housed sewing machine repair sweatshops to a trendy community that was clustered with sushi bars, nightclubs, exercise studios and supermarkets.

The flea markets, which previously seemed to proliferate like mushrooms, were reduced to a single open air lot between Fifth Avenue and Sixth Avenue on 25th Street, the indoor garage flea market and the only antiques center left, The Showplace Antique Center across from the open air lot.

Sensing the shrinking climate of the antique area, I purchased some property at 110 West 25th between Sixth and Seventh, one block from the flea market, and opened an auction house, hoping to attract more antique businesses to the area. I was open for only one year, when a realtor offered me four times what I had paid for the property. I realized why the flea markets and antiques centers and shops were all leaving. The real estate had soared in value.

A year later, the garage flea market closed, the building had been sold for a rumored $80 million. In its place, developers started to build a Marriott Renaissance Hotel.

Just this week, I learned of two more antiques businesses that were closing or planning to move, because the rents doubled or tripled.

One of the regular dealers, who identified himself as “Curtis” and regularly looks for sculpture and military items, lamented the change. “There are fewer items to look at,” he said, noting that many of the dealers he knew have stopped coming. He also blames online auctions and the Internet in general for helping to reduce the number of sellers, but acknowledges the real estate situation has been “transforming” the area. He said he still manages to find items, and still enjoys coming to the area for “the hunt.”

The Future

Dealers and collectors who come to the area every weekend, who previously gathered in coffee shops and cafes to debate the prices of Art Deco lamps or show their latest score buried in their pocket, now talk about the worrisome future of a antiques market area they see shrinking before their very eyes.

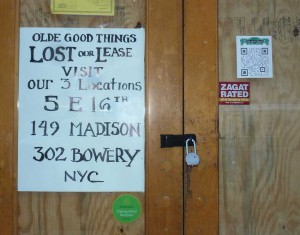

Rumors abound about the leases and “shelf life” of the remaining shops, antiques centers and the “open air flea market in the church yard” as dealers refer to it now, the one remaining flea market that so many dealers and collectors pilgrimage to.

Although flea markets appear and disappear in Brooklyn and Queens, New Jersey and Connecticut, dealers and collectors in the area hold out hope that the area will survive the real estate boom.

As one dealer put it, “It’s probably always going to be some semblance of an antiques market. People usually are more comfortable with the familiar.”