WORCESTER, MASS. – The Worcester Art Museum, in collaboration with Clark University, will present a new exhibition of portraits of people of African American and Native American descent. On view October 14-February 25, “Rediscovering an American Community of Color: The Photographs of William Bullard” provides a window into an American community of color following Reconstruction into World War I, a period of African American US history that is often overlooked.

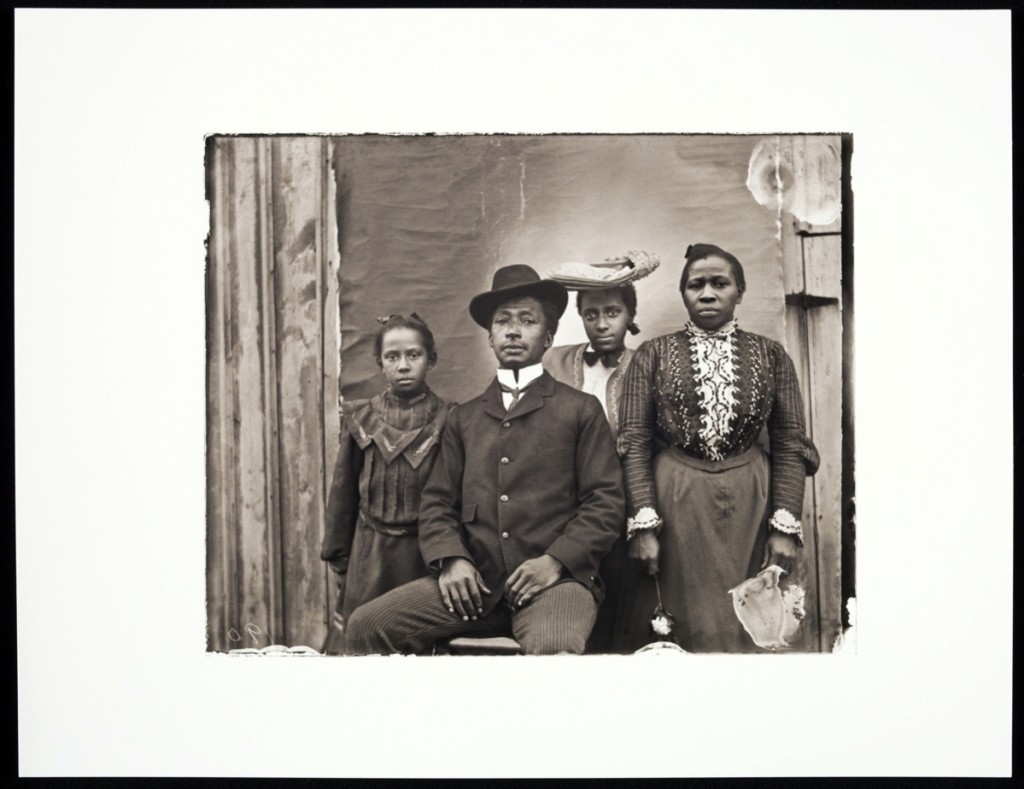

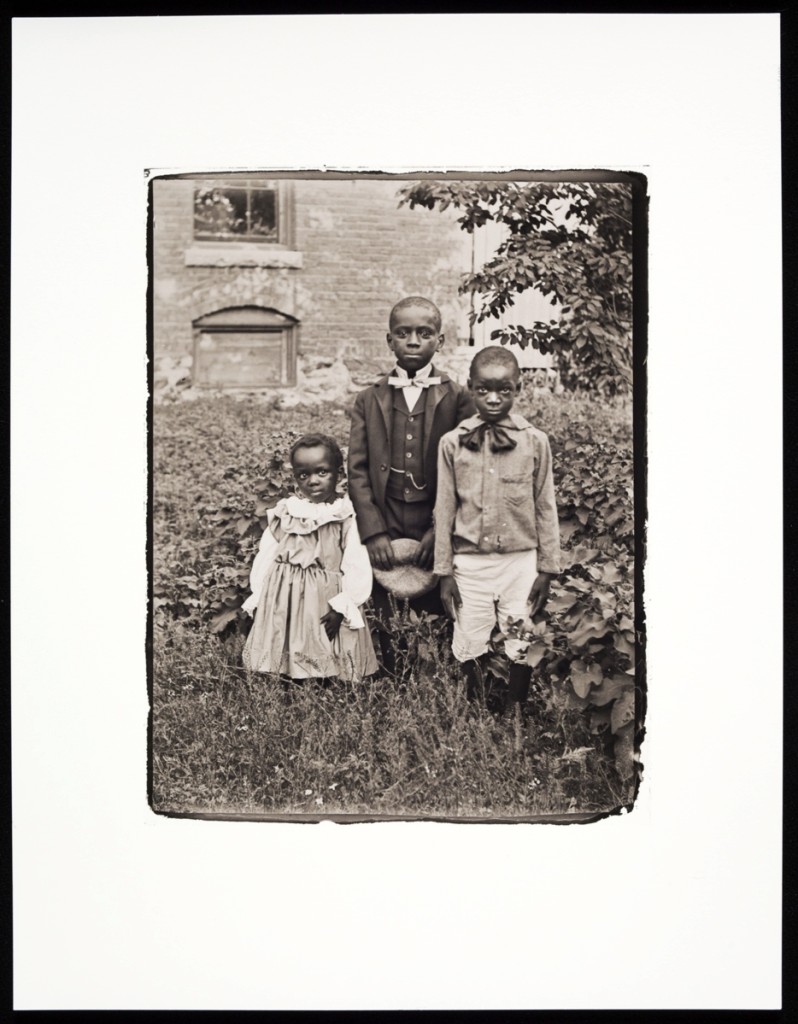

This is the first exhibition drawn from an archive of more than 5,400 glass negatives left behind by Bullard, a white photographer active in Worcester and across central Massachusetts between 1897 and 1917. Taken primarily in Worcester’s Beaver Brook neighborhood, where Bullard also lived, these images offer a look at a community made up of recent Southern migrants, people of Native American descent, black Yankee families and a handful of immigrants from the Caribbean. The exhibit includes 80 prints made from Bullard’s glass negatives.

Unusual for the period, Bullard left behind a logbook identifying the names and places of nearly 1,000 of his photographs, including more than 80 percent of his portraits of people of color. This makes the collection especially rare, as it is possible to tell the personal stories of many of Bullard’s sitters.

Co-curated by Nancy Kathryn Burns, the museum’s associate curator of prints, drawings, and photographs, and Janette Thomas Greenwood, professor of history at Clark University, the project brought together scholars, students, descendants of Bullard portrait sitters and community members. Working with Frank Morrill, owner of the Bullard collection of negatives, Greenwood connected with many living descendants, collecting valuable oral histories. Clark University students, who helped research the photographs and prepare the exhibition, also met with descendants and gathered family stories that provide context for the photographs.

“While recognizing the beauty and significance of Bullard’s works to the history of photography, this exhibition – and the related research and oral histories – also demonstrate how valuable such works can be to understanding our community in the present,” said Jon Seydl, senior director of collections and programs.

In the two decades before the Civil War, as the abolitionist movement gained strength, Worcester earned a reputation as a welcoming city, a place that offered jobs and opportunity, as well as a community of people sympathetic to the anti-slavery cause. As a result, Worcester continued to draw migrants during and after the Civil War, especially among African Americans from the South who were looking for new opportunities in the North. However, like many northern communities that saw an influx of outsiders, Worcester had become a far less welcoming place by the time Bullard took his photos, with an informal color bar in local industry that kept most people of color in service occupations. Despite discrimination and few resources, people of color built a strong and lively community, which is captured in Bullard’s portraits.

Contemporaneous with the “New Negro” movement, Bullard’s images depict confident and well-dressed citizens, and with many of the same fashionable accessories – like bicycles and riding attire – consistent with representations of white Americans of the same period.

For example, 36 of Bullard’s negatives capture members of the Perkins family, the largest single family represented among his photographs. Celia and Edward Perkins and their children and other family members acquired land in their native South Carolina after the Civil War but, in the economic decline that followed Reconstruction, they were forced to sell their land. Bullard’s images celebrate their reconstituted family safely in Worcester.

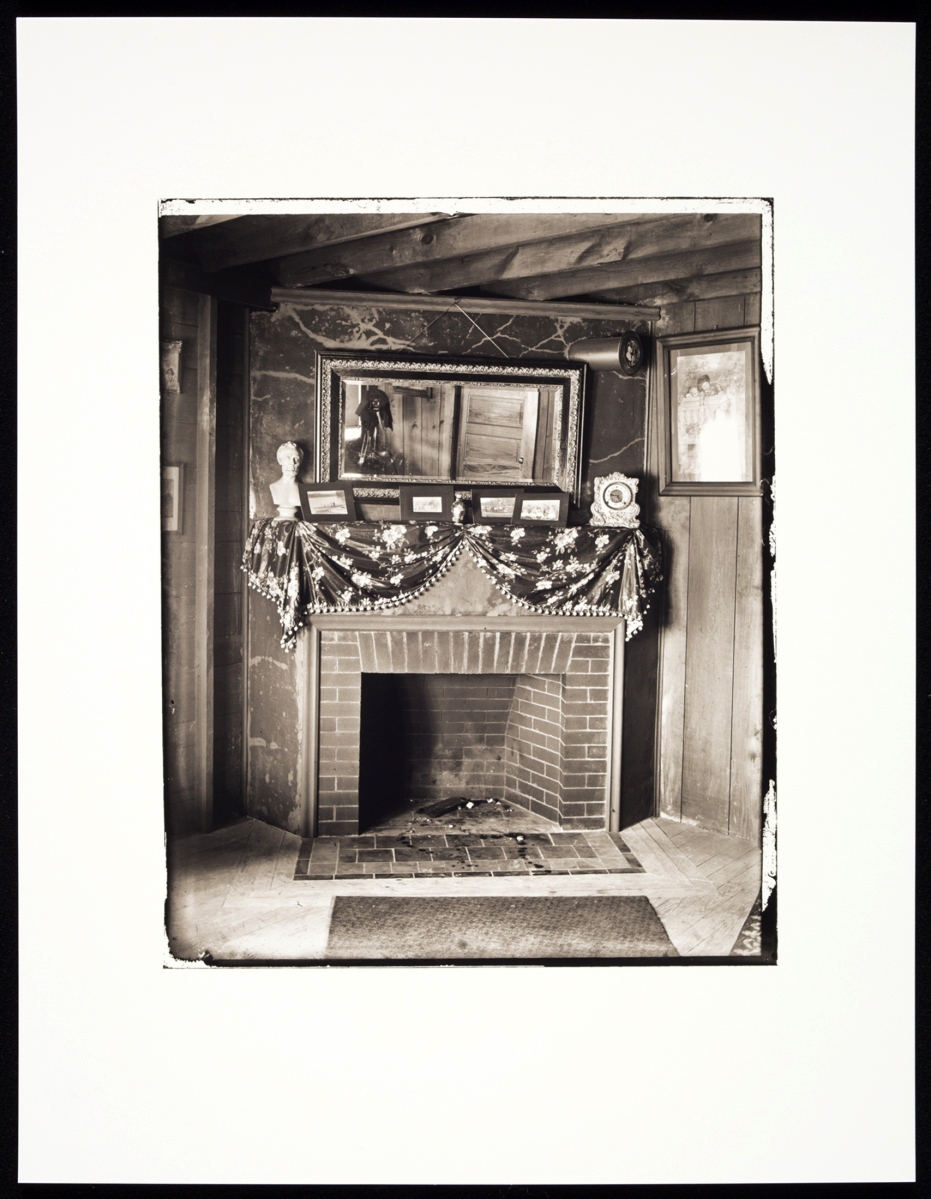

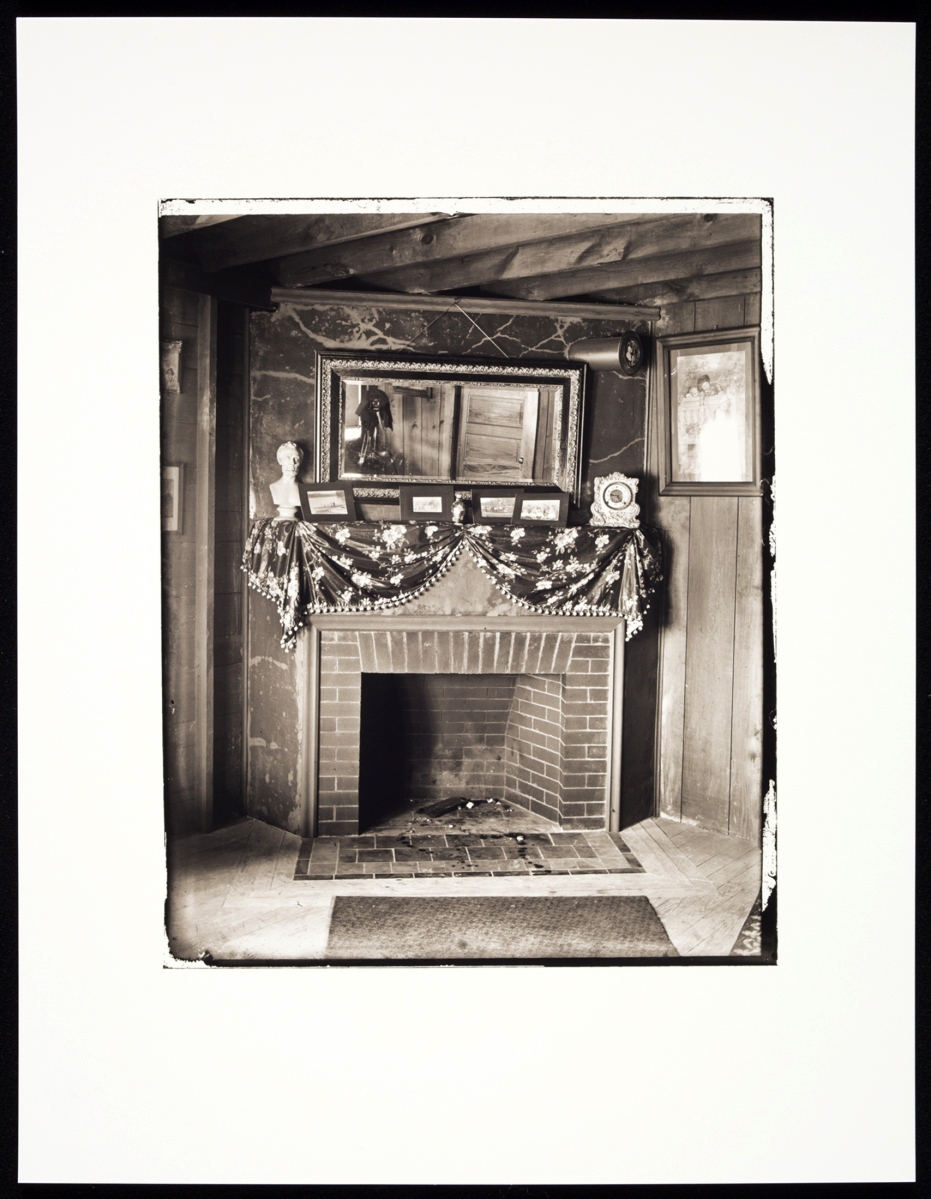

“William Bullard’s photographs show everyday people in their own settings, in their front yards, backyards and parlors, capturing an important moment in their history and ours,” according to Nancy Kathryn Burns. “While posed, many of his sitters demonstrate agency in the way they chose to engage with the camera. The fact that Bullard was a neighbor to so many of the people photographed likely informs the more relaxed demeanor of several sitters, despite the fact that he was white.”

A website, www.bullardphotos.org, will provide supplemental information for the exhibition, and serve as a permanent virtual display of the Bullard photographs.

The Worcester Art Museum is at 55 Salisbury Street. For more information, www.worcesterart.org or 508-799-4406.