By Garth Clark, Guest Curator

BOCA RATON, FLA. – On view at the Boca Raton Museum of Art through April 8, “Regarding George Ohr: Contemporary Ceramics in the Spirit of the Mad Potter” is an international perspective that vibrates in time between the example of a Biloxi, Miss., potter and visionary, George Edgar Ohr (1857-1918) and sculpture by contemporary artists from four continents. The latter, who work in the fine arts on the very edge of the ceramic aesthetic, include Glenn Barkley, Kathy Butterly, Nicole Cherubini, Babak Golkar, the Haas Brothers, King Houndekpinkou, Takuro Kuwata, Anne Marie Laureys, Gareth Mason, Ron Nagle, Gustavo Pérez, Brian Rochefort, Sterling Ruby, Arlene Shechet, Jesse Wine and Betty Woodman. Providing a bridge between Ohr and today are two key and revolutionary figures from the recent past, Ken Price and Peter Voulkos.

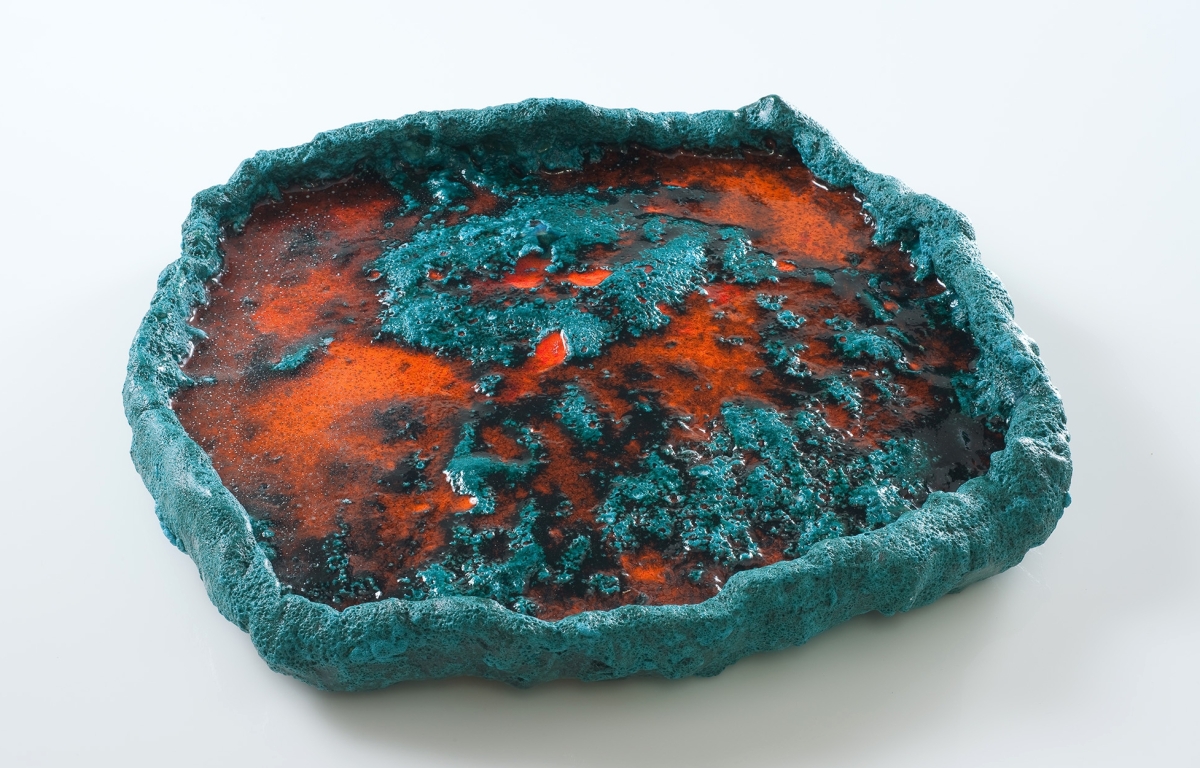

This is not a study in mimicry but more abstractly about their connective tissue, either by direct influence or happenstance, via radical manipulation of the vessel form, painting and extreme glazing and other issues, united by a curator’s eye.

Ohr was disregarded by the time he died and was not widely known in his day, rejected by the somewhat bourgeois bohemians of the American Arts and Crafts Movement (mostly an East Coast establishment) who saw him as a poorly educated Southern hick making tortured, grotesque eccentricities. He was largely forgotten by 1904 when he stopped making art, and only a few works existed teasingly in public collections.

In 1969, he made a dramatic reappearance. James W. Carpenter, an antiques dealer from New Jersey, stumbled upon the bulk of Ohr’s oeuvre, about 10,000 pieces, in the attic of an old building that belonged to the potter’s sons.

At first there was little reaction. Carpenter sold the works at the Smithsonian gift shop for $5 to $20. Slowly the word got out that something extraordinary had been discovered. An avant-garde talent from the beginning of century had magically come alive and was having his debut. The scholars and collectors of Arts and Crafts Movement material, true to form, at first sneered and ignored the event. Even in 1978 the keeper of ceramics at the Smithsonian, objecting to a laudatory article I had written, said, “You may think he is America’s most first great studio potter and artist, we think he is just plain hokey.”

What made Ohr’s arrival all the more stunning was that on top of being a “new” artist, his work was remarkably contemporary in its look and feel, radical treatment of form, deliberately broken lips, twisted from near collapse, flowing experimental glazing and handles that were inspired, enraptured drawings. Unlike the Arts and Crafts world, the ceramics and fine arts communities were stunned. Indeed, the New York fine arts community became Ohr’s most eager and influential champion. They recognized him as a peer, a gifted artist and a major one to boot.

Dealers (Irving Blum, Charles Cowles) and artists (Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns and others) became avid collectors. Johns even featured Ohr pots in his paintings and prints. He asked for the enlargements we made of Ohr’s inventive self-portraits for a show at my New York gallery after the exhibition closed to hang in his studio. Eventually the Arts and Crafts folks threw in the towel and joined the growing revival of interest in the so-called “Mad Potter of Biloxi.”

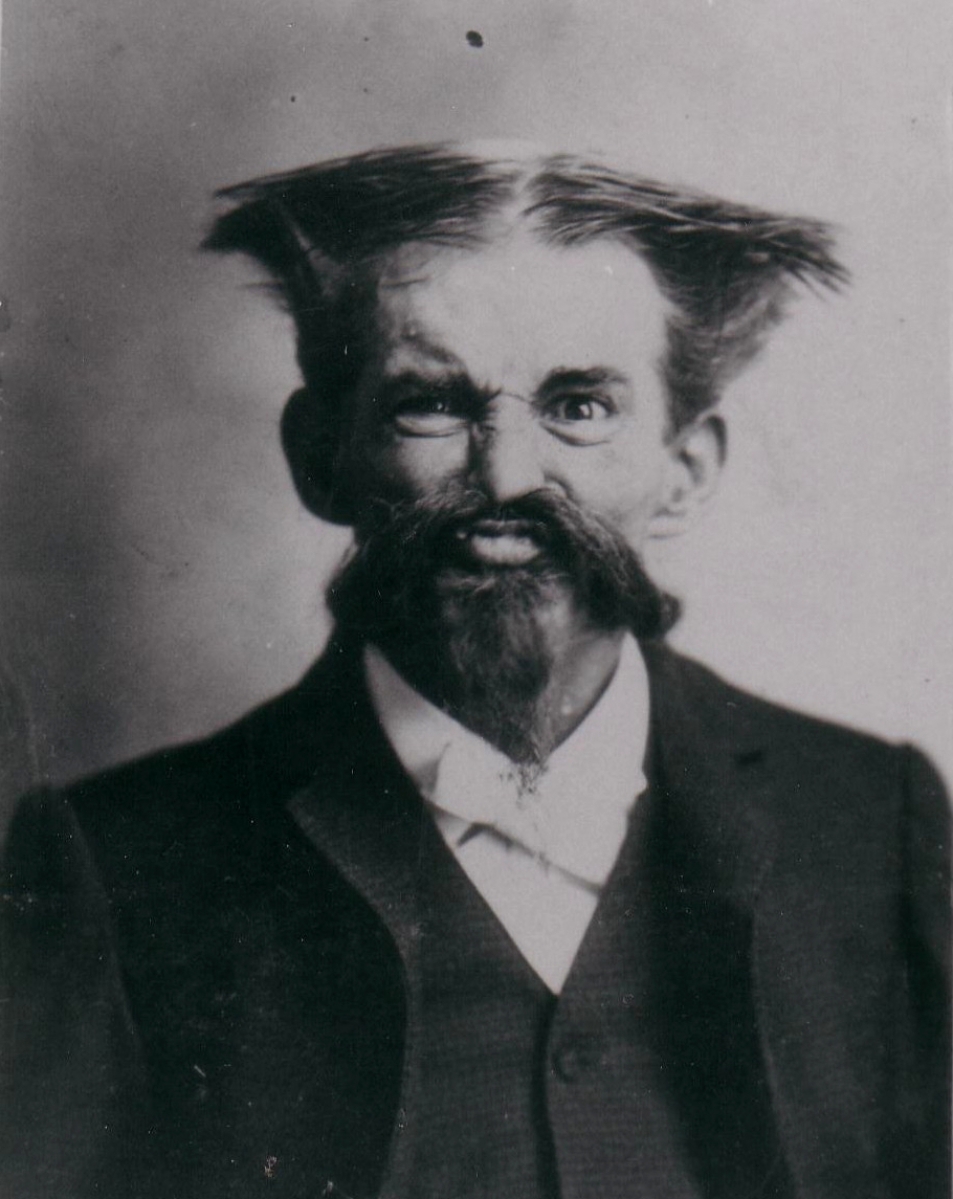

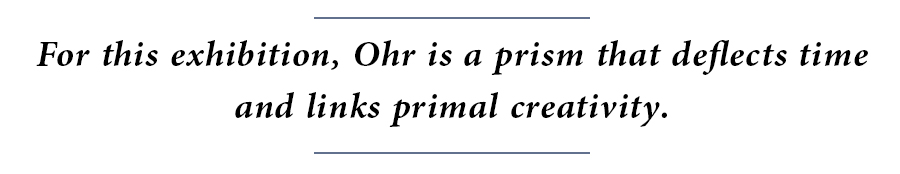

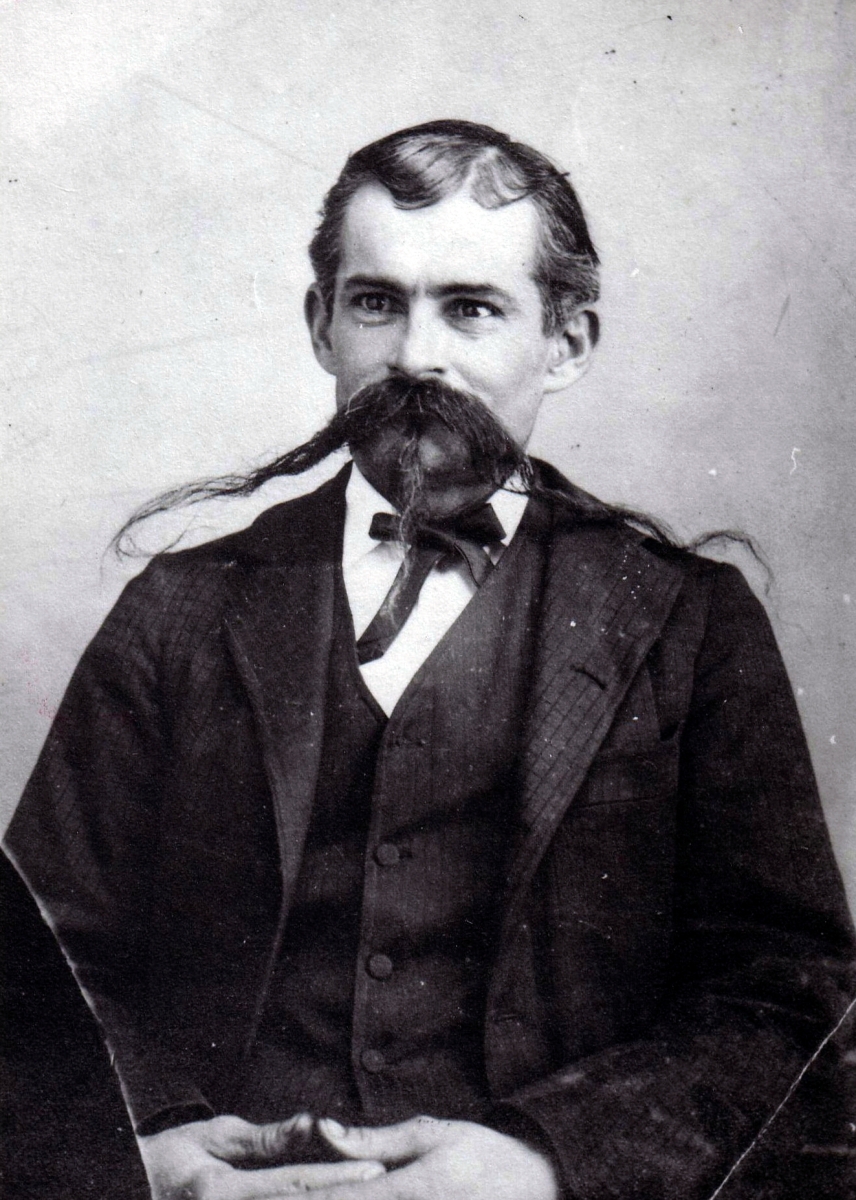

Ohr is the playful, mustachioed muse for this exhibition. His career included what we today call performance art, Dada gestures and art photography with the artist as subject, now a common genre. He was an Abstract Expressionist potter before Peter Voulkos, and was using Funk art language before Robert Arneson, both of whom arrived in the 1950s.

Ohr always said he would be best understood by future generations, hence his reluctance to sell his work. And that has come to pass. Several major monographs have been published, and a major retrospective toured the United States. His prediction that “the nation will erect a temple of my genius” happened as well.

The Ohr-O’Keefe Museum in his hometown of Biloxi was built and designed by none other than Frank Gehry, who joked with me, “I was shocked when I saw my first Ohr pot. I decided that one of us was copying the other. I decided that Ohr was mimicking me.”

For this exhibition, Ohr is a prism that deflects time and links primal creativity. The premise is not that all these contemporary artists were directly influenced by him. Some were, but a few had barely heard of him before they were invited to this exhibition. The purpose was a comparative study about artists, all working with the same tool kit Ohr had pioneered, all decidedly irreverent in their processes and all highly informal in their use of form (an exception being Ron Nagle’s precise cups and Babak Golkar’s streamlined “screaming pots.”) Just like Ohr, many of them were highly controversial and faced scorn from critics for changing rules, rejecting symmetrical elegance and bringing raw, rude emotion to the surface.

Untitled sculpture by Takuro Kuwata, 2016. Porcelain, stone, glaze, pigment, gold, lacquer; height 22-4/5 inches. Courtesy the artist, Salon 94, New York, and Alison Jacques Gallery.

For me the excitement was looking at the intense variety that grows out of five to six primary elements. They have enough in common for the exhibition experience to equip the viewers with a visual language that gives access to art that has often been described as impenetrable. It expands and enriches a new critical lexicon that certainly did not exist in Ohr’s day and even today perplexes contemporary writers who use terms like “sloppy” or “inept” when the work is neither.

The exhibition begins with an entry gallery containing a select group of major vase forms by Ohr from the famous, definitive collection of Marty and Estelle Shack. Many works have not been publicly shown before. Their sensuality borders on the erotic, their bright palette sets one’s eyes alight. Their forms undulate and shimmy. Handles dance with disturbing reptilian sinuosity, a floor show preceding the raucous contemporary party that beckons ahead.

Guest curator Garth Clark is editor-in-chief for CFile ‘s publishing projects, journal and news magazine, and is a Fellow of the Royal College of Art, London, with several honorary doctorates and lifetime achievement awards. He is author of more than 60 books and hundreds of reviews and essays. Clark has spoken on five continents in 30 countries at more than one hundred major venues from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to the Sorbonne in Paris.

With thanks to the Boca Raton Museum of Art for granting permission to reprint this essay.

Related programming includes, on Saturday, February 17, a demonstration by Dr Thomas Stollar, ceramicist and Florida Atlantic University assistant professor; on Saturday, March 3, “A Day in Clay,” a guided tour of the exhibition followed by a box-lunch lecture with scholar Terryl Lawrence and a demonstration by ceramic sculptor Jeff Whyman; and, on Thursday, March 15, a lecture by Eugene Hecht, Adelphi University professor and author of George Ohr: The Greatest Art Potter on Earth.

The Boca Raton Museum of Art is in Mizner Park, 501 Plaza Real. For information, www.bocamuseum.org or 561-392-2500.