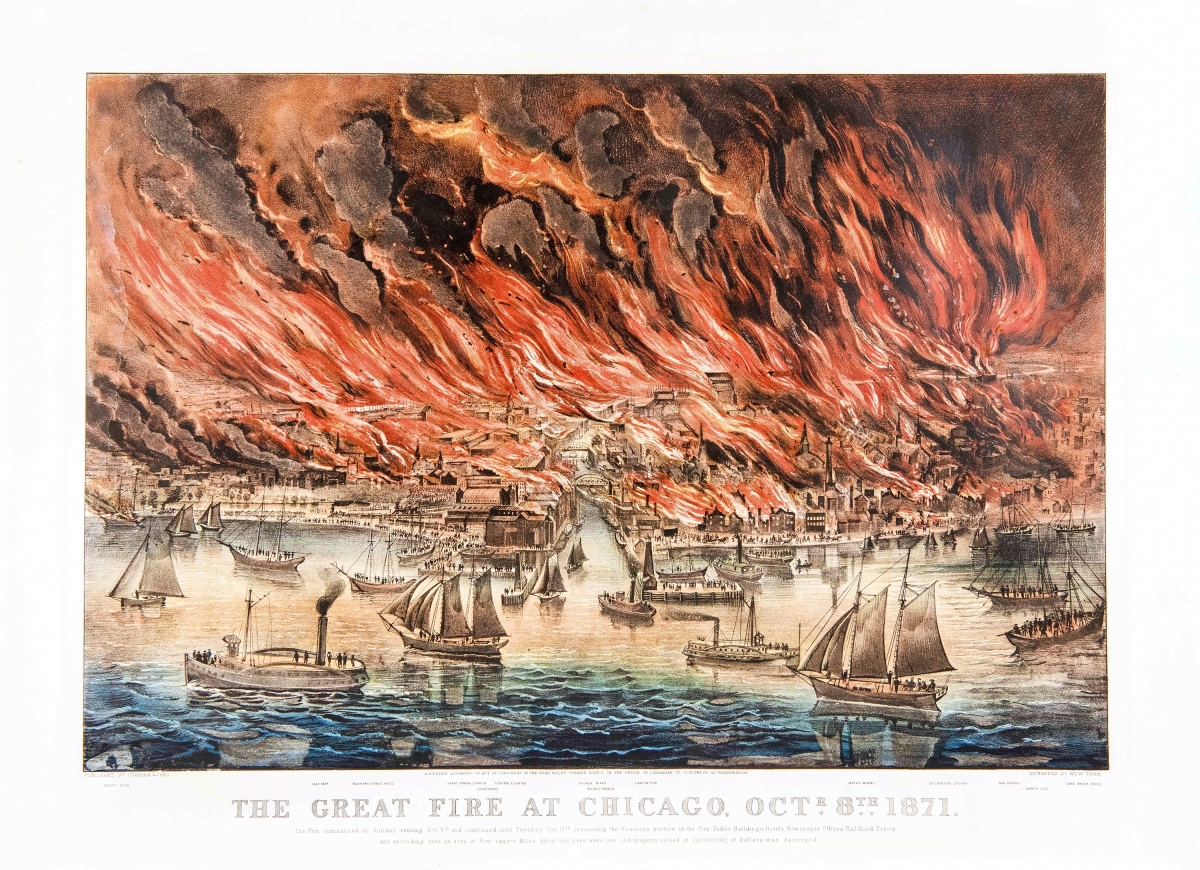

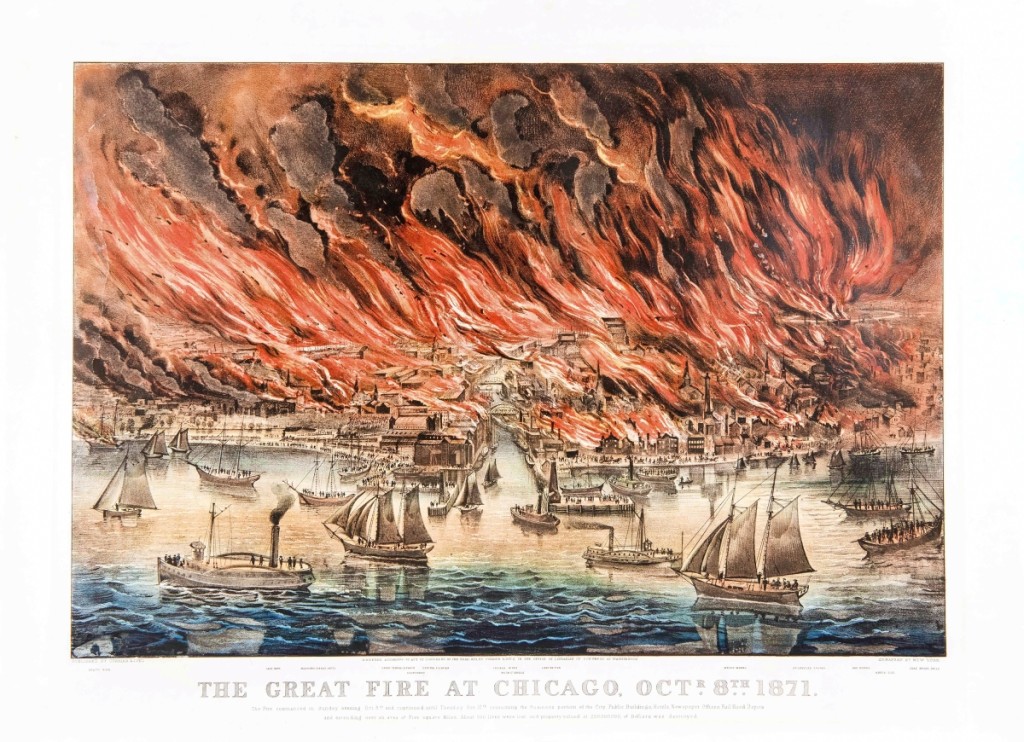

“The Great Fire at Chicago, Octr. 8th. 1871,” 1871. Lithograph, image size 17 by 25 inches. The Great Chicago Fire consumed over three-square miles of the city, killed roughly 300 people and left nearly 100,000 homeless. Popular lore placed the blame on the O’Leary family’s cow, said to have kicked a lantern over into a pile of hay.

By Laura Beach

OLD LYME, CONN. – “I’ve always been fascinated by Currier & Ives. Our contemporary culture owes much to the firm’s popularization of mass imagery,” says Florence Griswold Museum curator Amy Kurtz Lansing, musing on the perennial interest people have in the makers of the mid-Nineteenth Century American lithographs filling the museum’s Krieble Gallery on view to January 23.

Organized by Omaha’s Joslyn Art Museum, “Revisiting America: The Prints of Currier & Ives” takes a new look at these colorful records of American life, recognizing deeper truths in their often idyllic, occasionally sensational depiction of the past. “The richness of these images is what they tell us about Nineteenth Century culture and its aspirations, but we should not accept them as transcriptions,” Lansing warns.

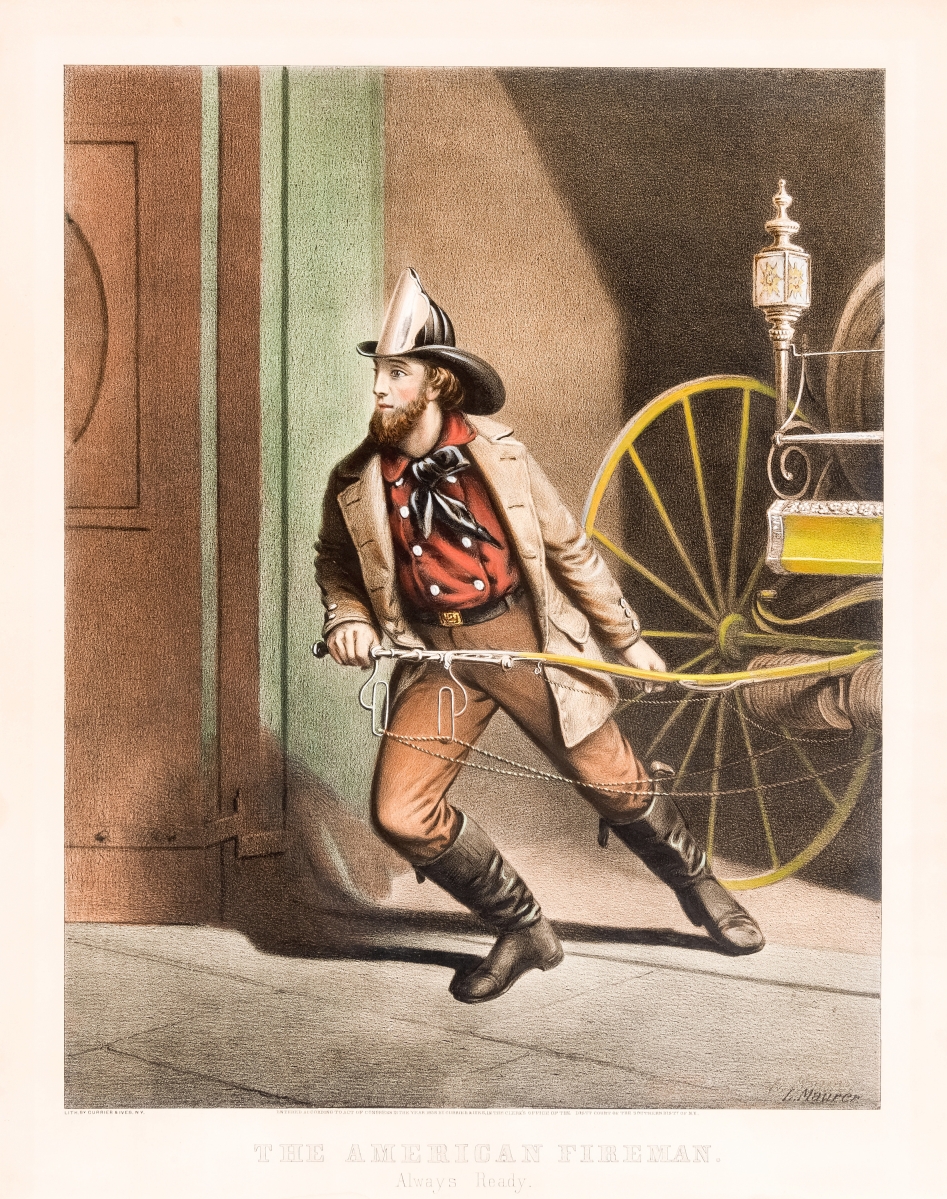

As recounted by Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, associate curator of fine arts at Winterthur Museum, in the show’s accompanying catalog, the success of the company founded in New York in 1834 resulted from its marketplace savvy, including its canny alliances with talented artists, among them Louis Maurer (1832-1932), Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819-1905), Eastman Johnson (1824-1906), James E. Buttersworth (1817-1894), George Inness (1825-1894) and George Henry Durrie (1820-1863).

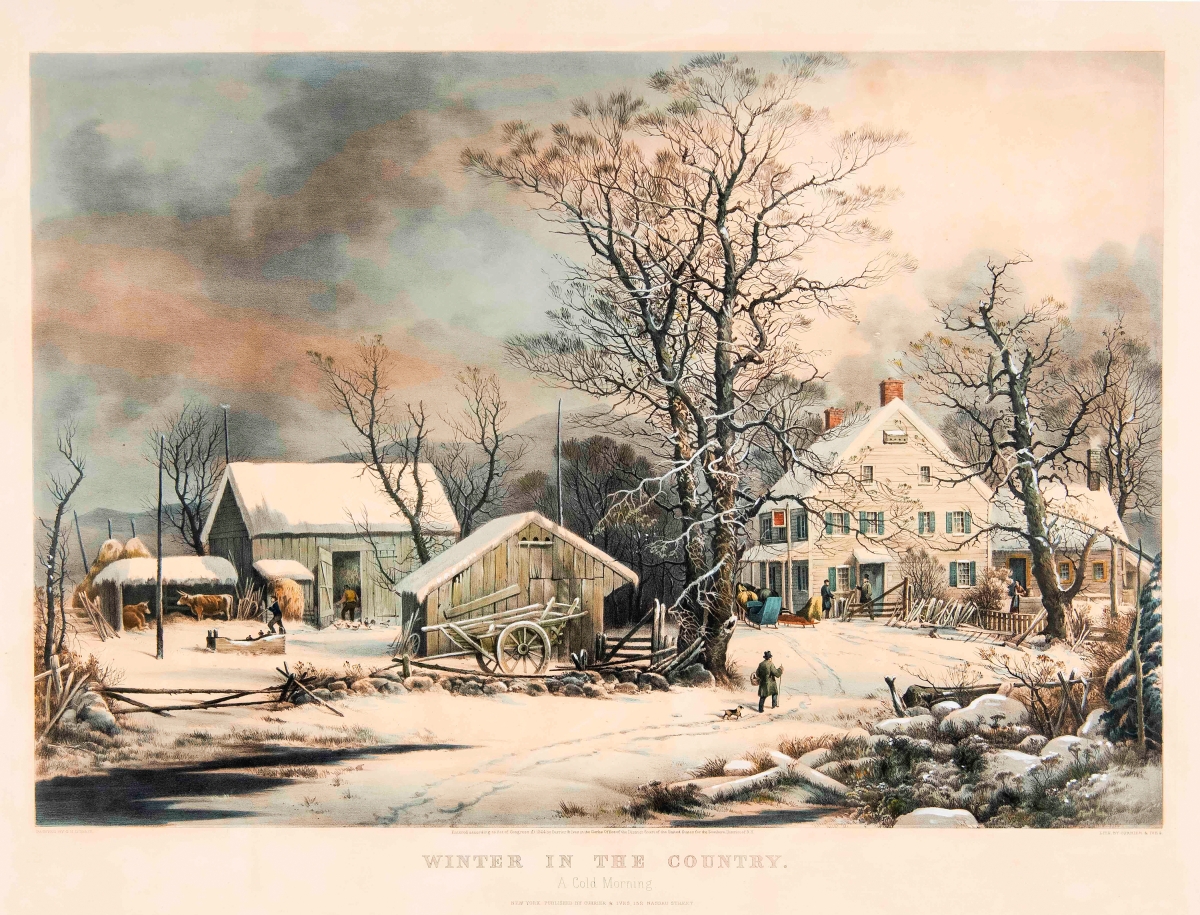

It was the Connecticut-born Durrie, famous for his charming winter pastorals of snow-dusted farms, who most interested the Florence Griswold Museum’s staff. As Lansing explains, “If you mention Currier & Ives to people, whether they realize it or not it’s probably a Durrie that comes to mind because of the way his images appeared on Christmas cards and in calendars. Durrie is represented in our collection, and we did ‘SEE/change,’ an online learning module for teachers based on his circa 1853 painting ‘Seven Miles to Farmington,’ which as a work of art and a historical document is a wonderful teaching tool.”

The self-described “Grand Central Depot for Cheap and Popular Prints,” the firm originally known as N. Currier was started by Boston-trained lithographer Nathaniel Currier (1813-1888), who in 1857 took as his partner James Merritt Ives (1824-1895). Graduating from printing on commission to publishing images of its own design, Currier & Ives capitalized on the booming market for inexpensive images made possible by lithography, invented in 1819 and in widespread use after the 1820s.

“Central-Park, Winter: The Skating Pond” by Charles Parsons, 1862. Lithograph, image size 18 by 26-5/8 inches. New York City’s Central Park was a popular subject for Currier & Ives, which published more than a dozen images of leisure activities there.

The medium was the message. “Identifying and satisfying the tastes of that market was the chief success of their enterprise,” writes catalog essayist Michael Clapper. “The initial investment in equipment and skilled labor was large, and so popular art could only be profitable, and thus could only remain viable, by deliberately trying from the outset to create art that many people would like.”

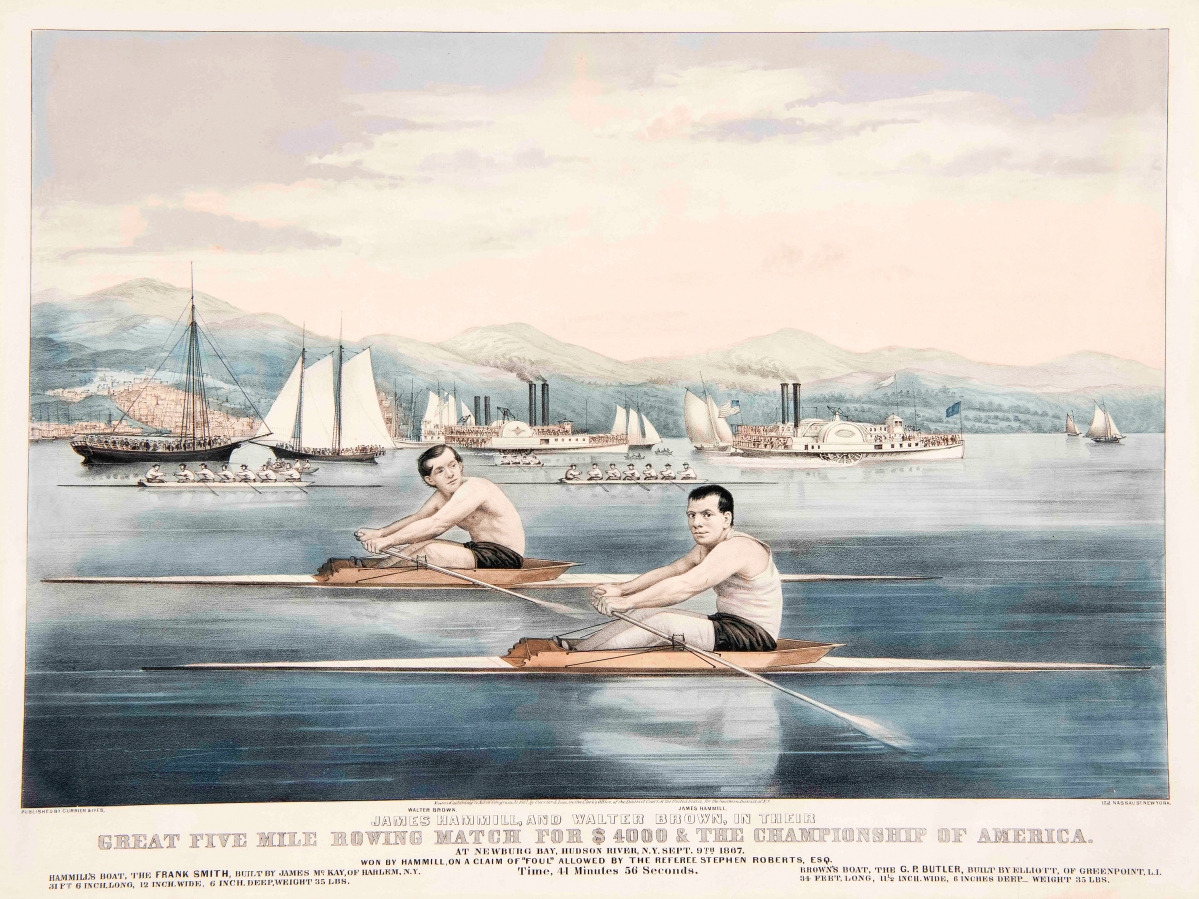

The most complete listing of Currier & Ives prints, Bernard F. Reilly Jr’s two-volume catalogue raisonné of 1984, lists 7,500 images. They range from the sentimental to the sensational. Artists, draftsmen, lithographers, pressmen and colorists contributed to the inventory, which Currier & Ives sold from two locations in New York City – 152 Nassau Street and 33 Spruce Street – and distributed directly to customers by mail and through regional representatives.

Most Americans could afford a Currier & Ives print. According to Delamaire, “The cheapest images were small, plain lithographs printed in black ink and sold either uncolored or coarsely painted for six to ten cents each. The costlier examples were large lithographs printed on the best papers and delicately hand colored by professional artists. These sold between $1 and $3.75 apiece…”

Collectors emerged even before the business closed in 1907. Writing in Best Fifty Currier & Ives Lithographs, Small Folio Size, published by The Old Print Shop in 1934, Charles Messer Stow described the activities of the collector Col. Henry W. Shoemaker, who frequented the Currier & Ives shop at 33 Spruce Street between 1893 and 1895. As Stow detailed, Shoemaker recalled “the unfailing courtesy and kindness of the clerks and their evident willingness to assist a young collector. His first request was for horse prints, and the clerk handed him a broadside about 7 by 10 inches in size with a great number of titles and opposite each a number. He mentioned the numbers he wanted to see, and the clerk got the prints from the wall cases bearing those numbers. There were sheets of thin brown paper between the prints in the boxes to keep them from rubbing each other.”

No dealer has more vigorously encouraged interest in Currier & Ives than The Old Print Shop. Not long after he acquired the business in 1928, Harry Shaw Newman – grandfather of the present proprietors, Robert K. Newman and Harry S. Newman II – collaborated with one of his best clients, collector and author Harry T. Peters, to organize a contest to select the best 50 each large and small folio Currier & Ives prints, whose values rose steadily in the 1920s. Stow, the antiques columnist for the New York Sun, took an avid interest in the competition, publishing the winning prints one at a time in the Sun in the early 1930s.

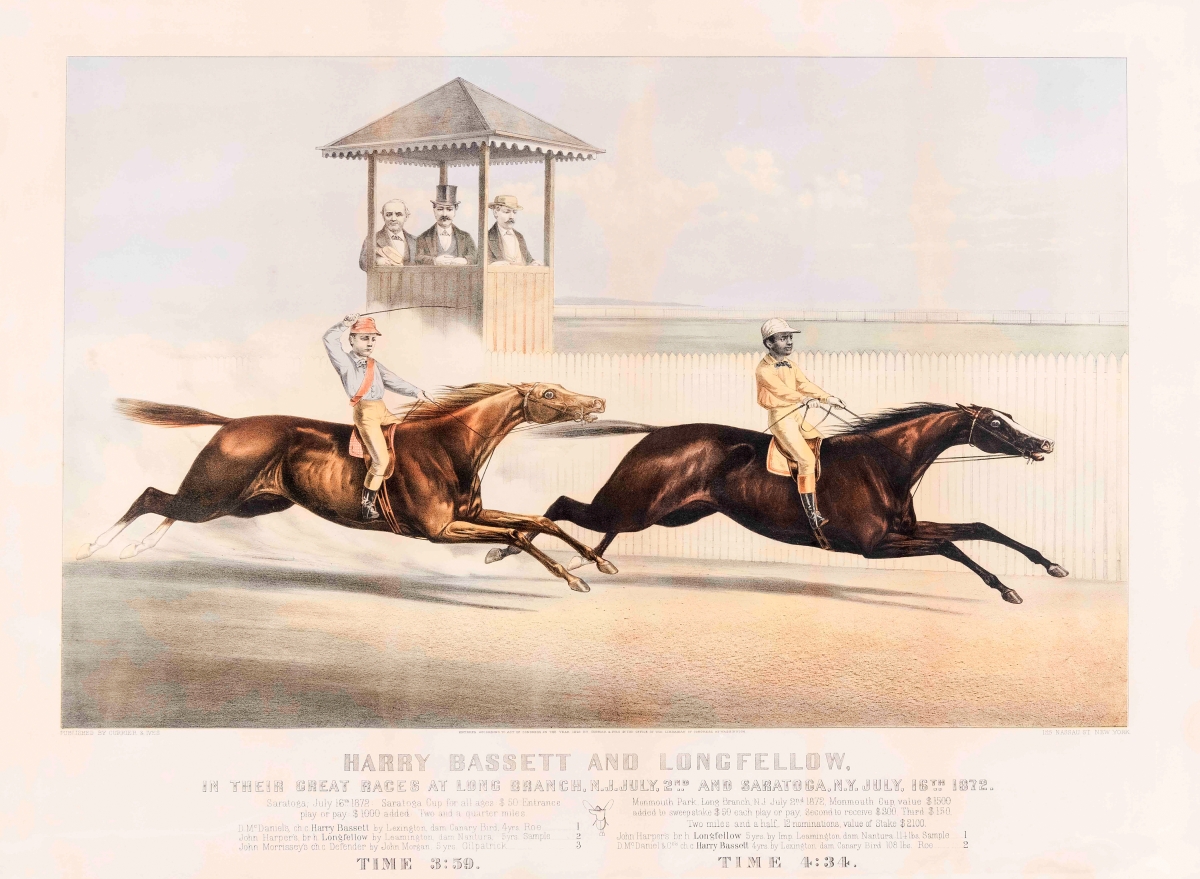

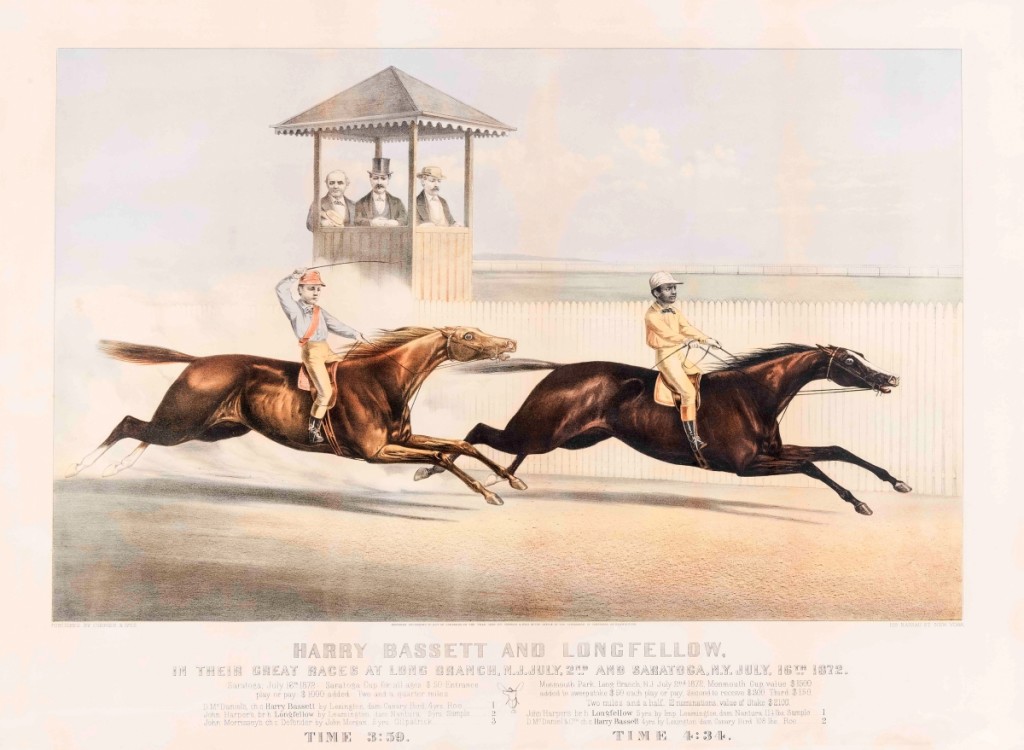

“Harry Bassett and Longfellow, in their Great Races at Long Branch, N.J. July, 2nd and Saratoga, N.Y. July, 16th 1872,” 1872. Lithograph, image size 16-7/8 by 26¾ inches. Currier & Ives produced more than 750 prints related to horse-racing, indicative of the sport’s popularity in the Nineteenth Century. Longfellow, right, is ridden by the African American jockey John Sample.

The Joslyn Art Museum exhibition has its roots in a relationship nurtured by Harry Shaw Newman’s son, Kenneth, with collector Roy King. A New Yorker, King acquired 672 Currier & Ives lithographs, many from The Old Print Shop, plus related documents and ephemera. In 1975, King sold the cache to Esmark, which over the next 15 years circulated it as a traveling exhibition to more than 116 museums, college galleries, department stores and corporate offices in 23 countries. Conagra acquired Esmark’s successor, Beatrice Companies, in 1990. In 2016 it donated the collection to the Joslyn Art Museum, which honors King and Newman’s achievement with the present catalog and traveling display.

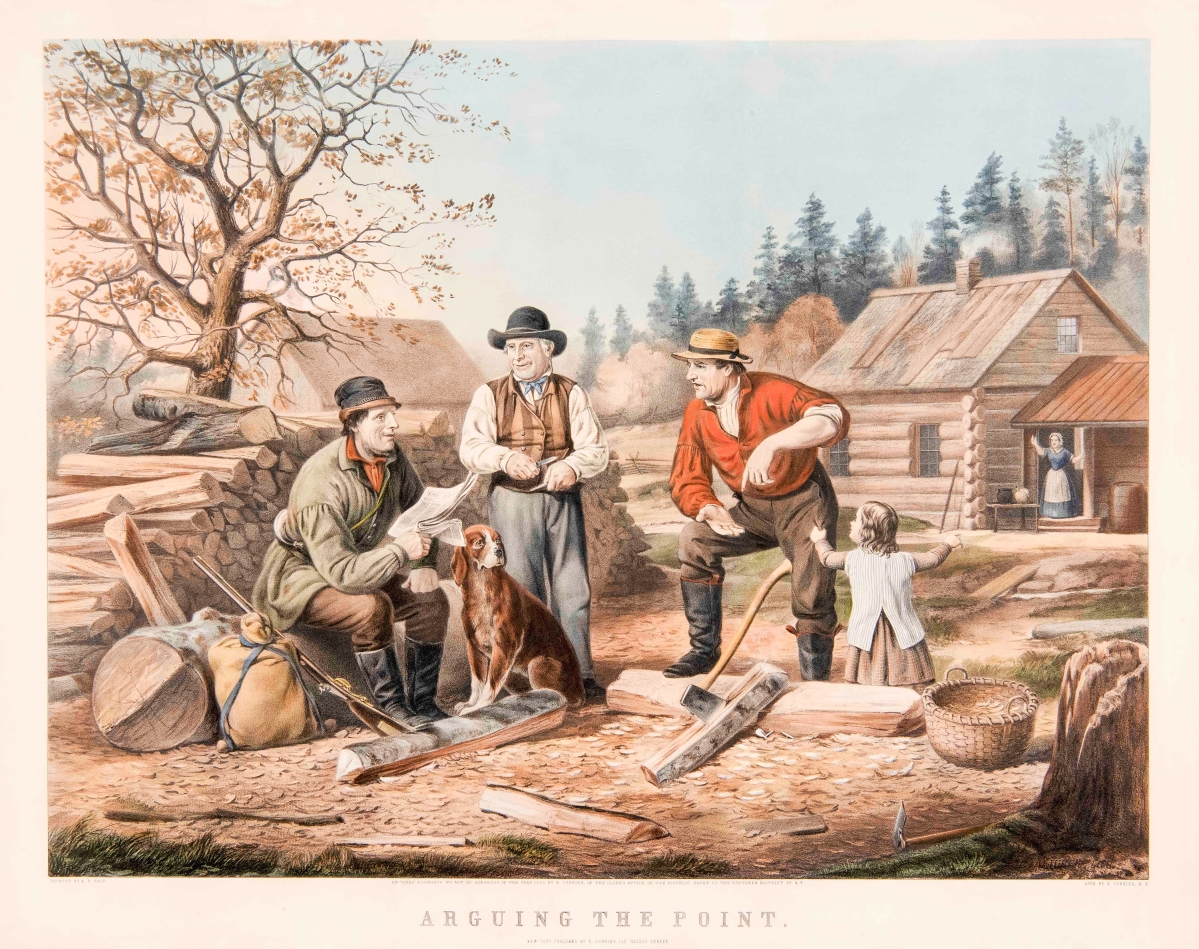

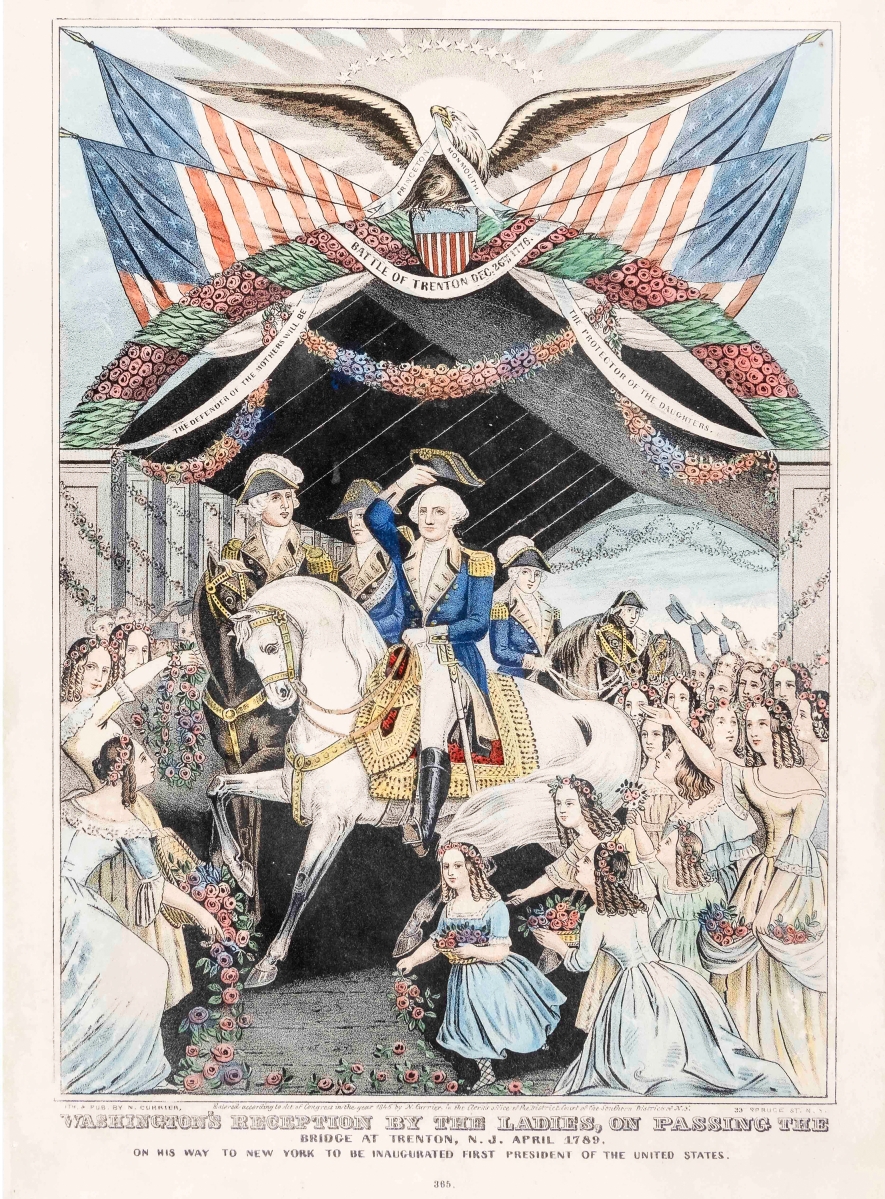

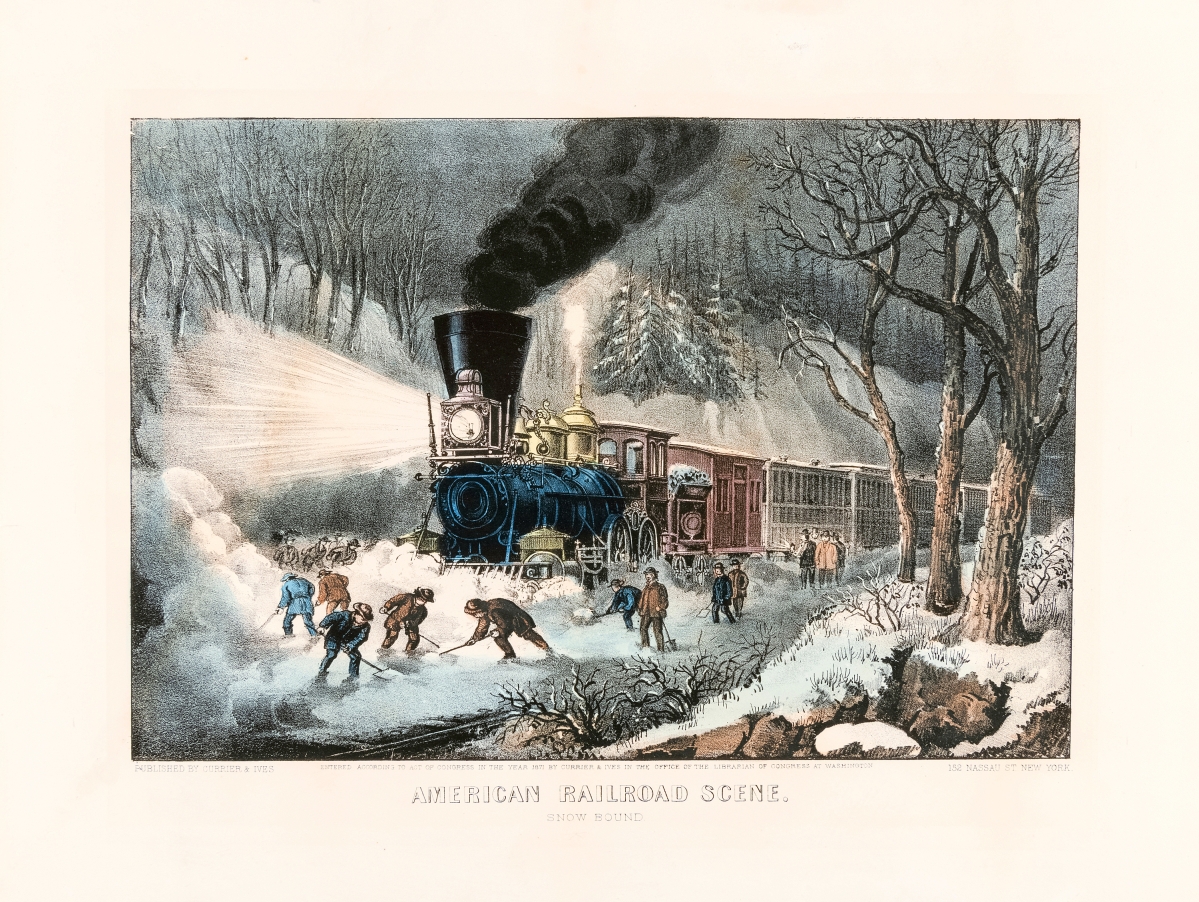

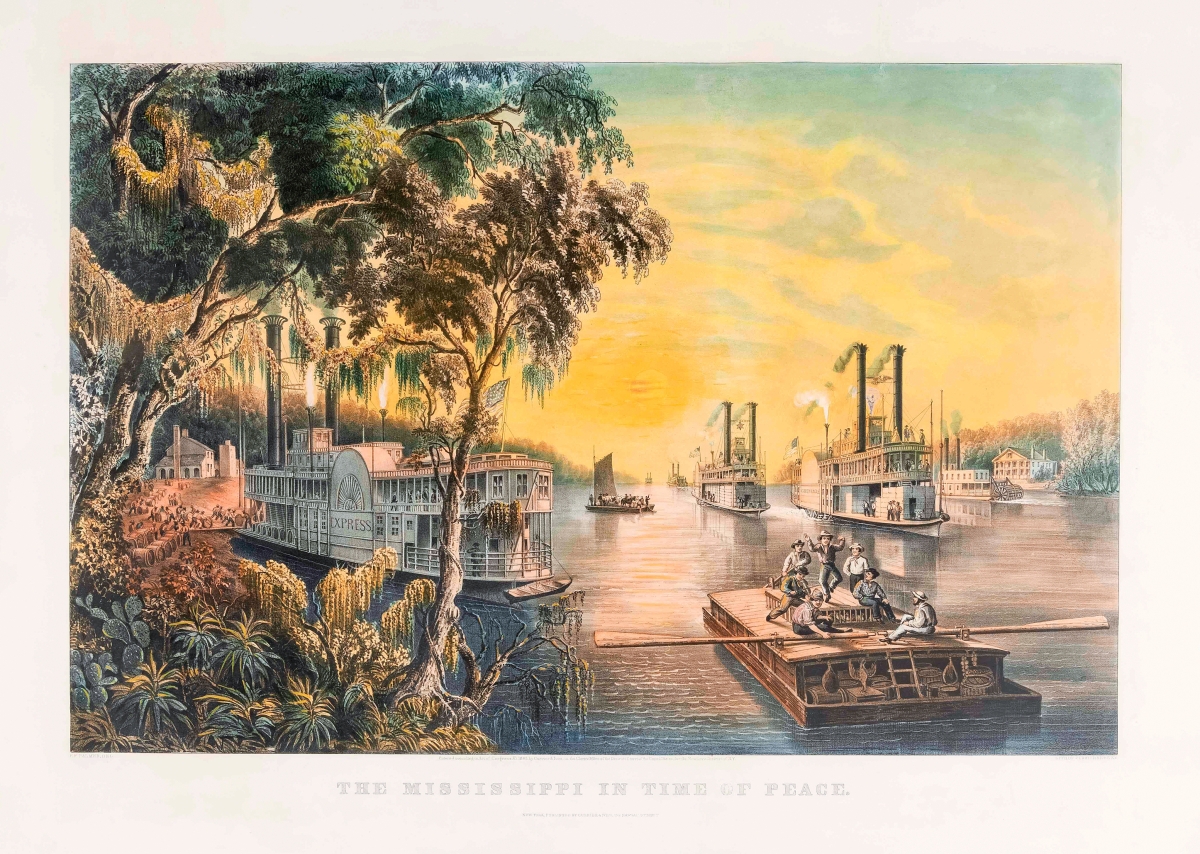

In an approach inviting analysis of Nineteenth Century taste, Lansing organized the roughly 65 prints in the show into broad themes: “Sails, Steam and Speed,” “Urban Experiences,” “Domestic Visions,” “Sporting Life,” “The Frontier,” “The South” and “America in War and Peace.”

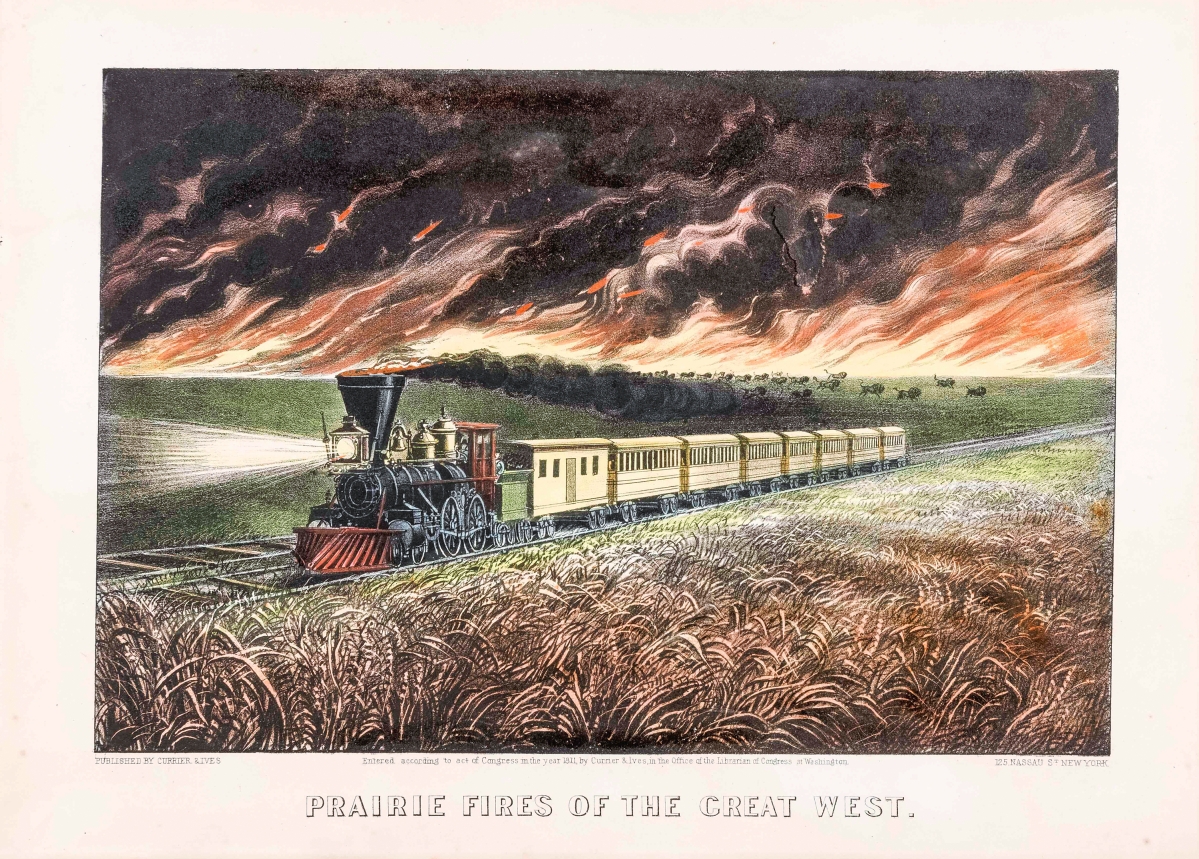

As emblems of the Industrial Revolution and Manifest Destiny, depictions of clipper ships, steamboats and trains were popular subjects, all the more so if the transportation behemoths faced disaster. Indeed, N. Currier’s breakout print was a view of the burning of the luxury steamship Lexington, which caught fire enroute from New York to Stonington, Conn., in January 1840. Delamaire writes, “The success of the Lexington image marks a turning point in the history of the American lithography industry. Its popularity demonstrated the public’s desire for sensational and dramatic colored lithographs, ushering in a decade of significant expansion for the industry.”

Scenes of hunting and fishing, as represented by the artist-sportsman Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait – Currier & Ives commissioned 42 paintings by Tait between 1852 and 1865 – were best-sellers, as were racing views. Many trainers and jockeys of the day were African American – 15 of the first 28 Kentucky Derbies were won by Black jockeys – and some were depicted by Currier & Ives.

Louis Maurer’s dramatic views of the West “present an optimistic attitude toward American progress and technology, but we also want to acknowledge the social cost of phenomena like building the transcontinental railroad, and the role of immigrant laborers in laying the track,” Lansing says.

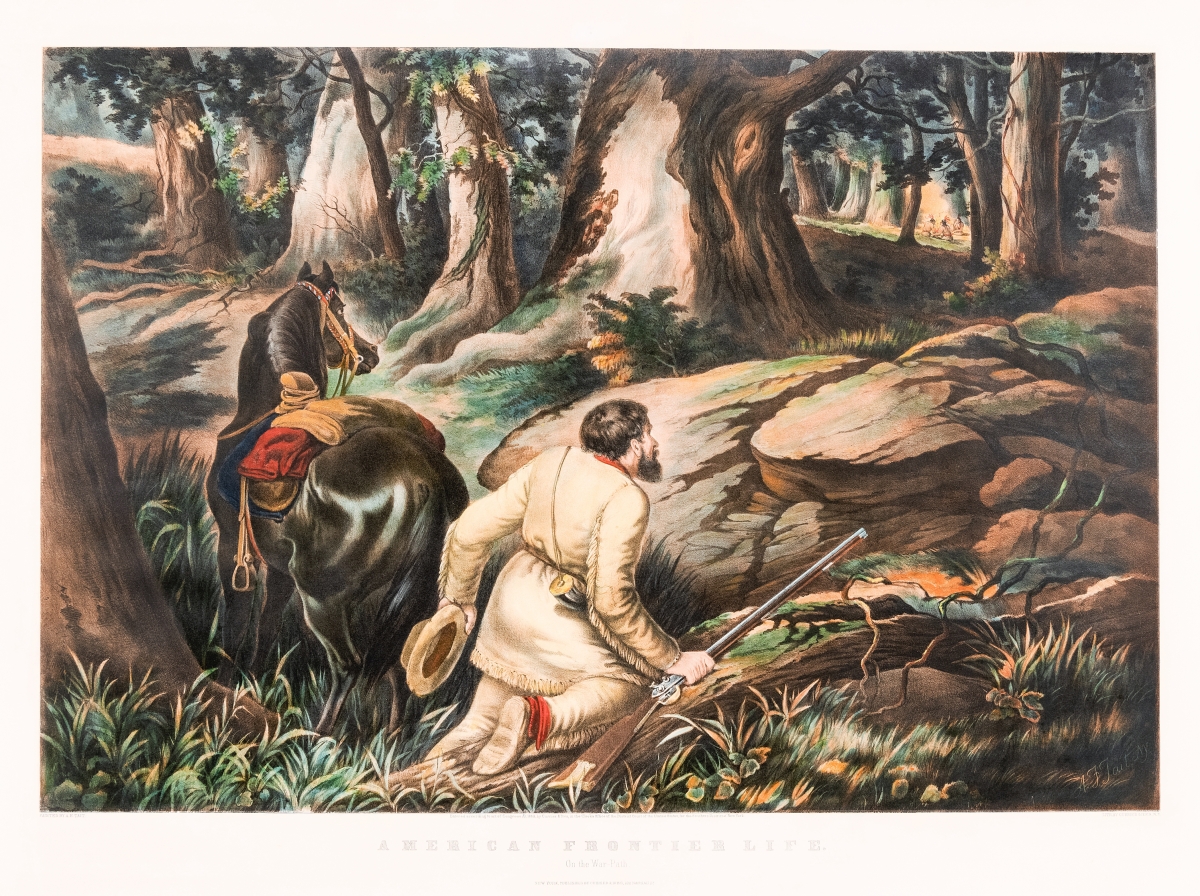

“The Prairie Hunter: One rubbed out!” by Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819-1905), 1852. Lithograph, image size 14-1/16 by 20-11/16 inches. Although Tait never traveled farther west than Chicago, he created many of Currier & Ives’ most popular Western pictures. This image borrows from William Ranney’s painting “The Trapper’s Last Shot.”

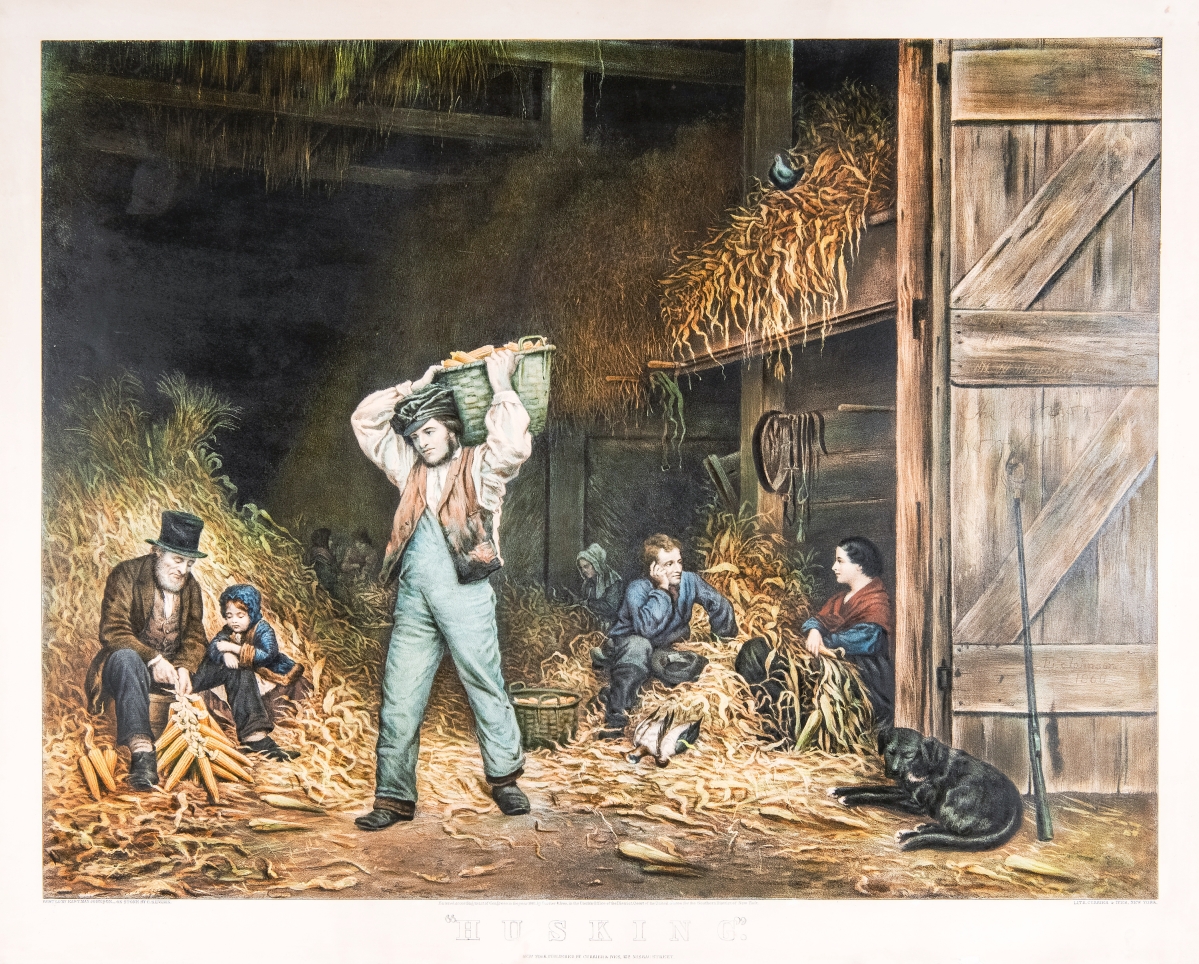

Northern in its perspective but moderate in its stance, Currier & Ives avoided searing views of the Civil War; ten years after the conflict ended it was offering nostalgic visions of the antebellum South.

Interested in the artists who made Currier & Ives the powerhouse it was, Lansing incorporated work by Durrie from the museum’s collection and turned her eye toward the redoubtable Fanny Palmer (1812-1876). Born Frances Flora Bond in Leicester, England, Fanny trained in London. With her husband, Seymour, she established a lithographic workshop before immigrating to the United States, where the couple collaborated with Nathaniel Currier as early as 1849. An undisputed star, Fanny worked independently, designing at least 200 of Currier & Ives’ most famous prints between 1851 and 1868. According to Delamaire, she likely tutored the initially inexperienced James Merritt Ives in lithographic technique.

Reproduced as Christmas cards, stamps and calendars, the art of Currier & Ives survives as a distinctly American expression. For Delamaire, “their lithographs have long come to define the democratic culture of Victorian America.” Lansing, who concludes her presentation with examples of Currier & Ives ephemera, notes, “The way these images were disseminated contributed to their popular embrace. Many people saw this Conagra collection when it toured, and many more remember the images from items their grandparents had in their houses.”

It is tempting to see Currier & Ives prints, alternately homely and heroic, as Nineteenth Century precursors to the work of Norman Rockwell and Twentieth Century artist-illustrators, and from there connect the printmakers to Hollywood’s mythmaking machinery, whose ethos is embedded in the new Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, set to open in 2023.

But Lansing suggests a finer shading, observing, “Narrative art provides a sense of relatedness and connection. I wouldn’t discount what Hollywood does, which is create images on a grand scale, but in Currier & Ives people recognize smaller moments that they identify with their own experience.”

Lansing concludes, “It feels like a good time to have another look at Currier & Ives. As a nation we are rethinking what America means to all of us. These prints are from a time when people were asking many of the same questions. They captured people’s imaginations then and do so now.”

Published by Joslyn Art Museum in 2020, Revisiting America: The Prints of Currier & Ives is edited by Melissa Duffes with contributions by Emma Westbrook, Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, Michael Clapper and Baird Jarman.

The Florence Griswold Museum is at 96 Lyme Street. For information, 860-434-5542 or www.florencegriswoldmuseum.org.

Unless otherwise noted, all works pictured are from the collection of the Joslyn Art Museum and were a 2016 gift to the museum by Conagra Brands.