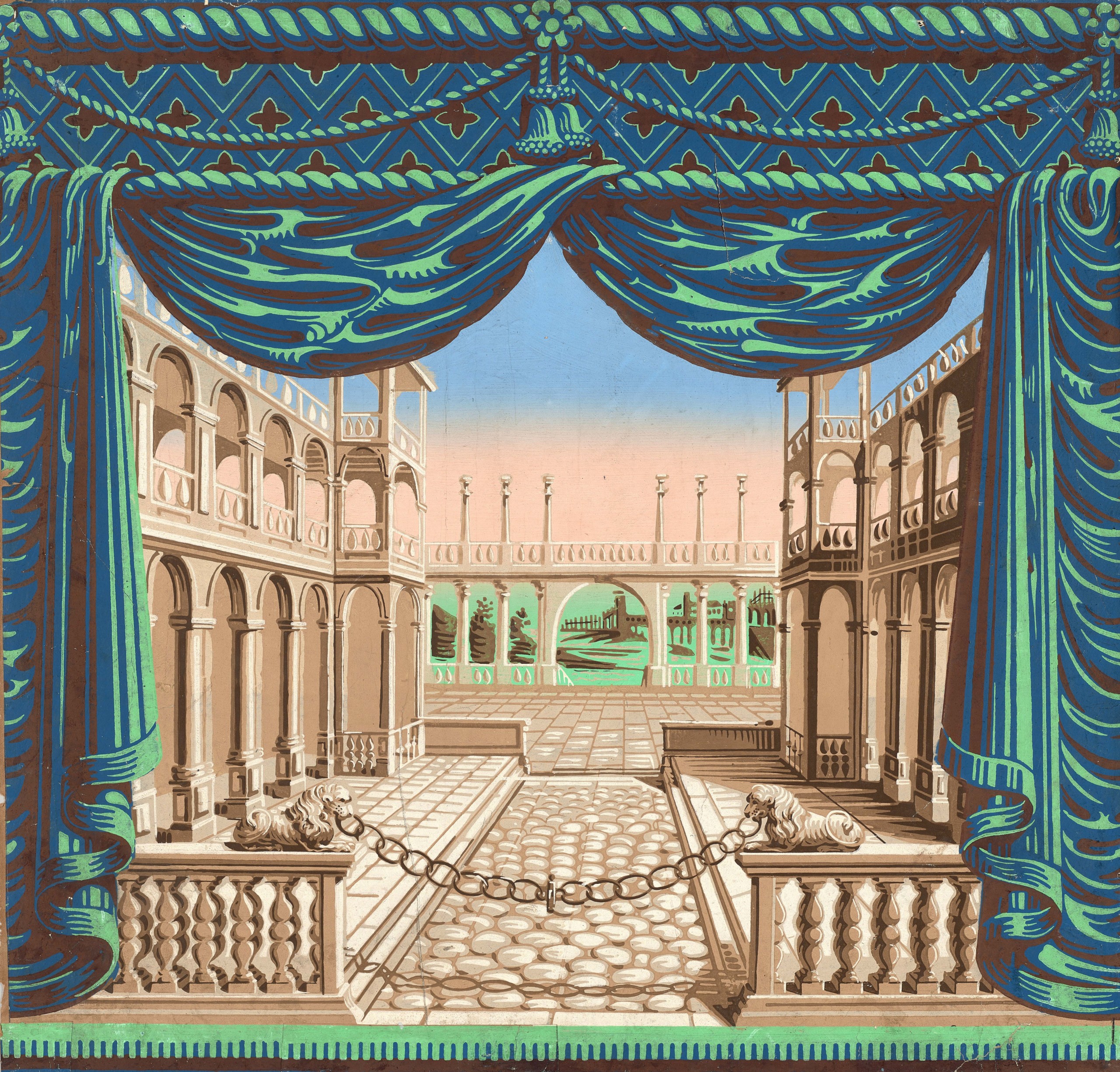

“View of Venice” wallpaper, French, circa 1840. Mary B. Jackson Fund. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

By Kristin Nord

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Beauty, innovation, social history and a detective story all in one. Whoever thought wallpaper had such a story to tell. And yet that’s what is before the viewer in the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum’s exhibition, “The Art of French Wallpaper Design,” on view through May 11.

When RISD acquired the Huard Collection in 1934, it was perhaps not fully aware of what a magnificent teaching collection it would turn out to be. But spectacular it is in many iterations, according to Emily Banas, the museum’s associate curator of decorative arts and design and this exhibition’s curator. The show is a paean to the golden era of French Eighteenth and Nineteenth century papier peint (painted paper) design and to the highly skilled and intensive labor that went into it.

The collection stretches from the early 1700s up through the 1840s, when mechanical roller printing ushered in a less labor-intensive product. Banas selected 100 works from the 500 in the collection — and they make for lively and vibrantly colored company. These rare examples of salvaged wallpapers, borders, fragments and design drawings simply must be seen in person to be appreciated.

“I am certain the material will excite our visitors and challenge notions of what ‘historic’ design looks like. From its foundations in drawing and printing, to its dynamic forms and creative uses that enlivened and personalized spaces, there is so much more to wallpaper than meets the eye,” Banas said. A comprehensive digital publication, The Art of French Wallpaper Design, is available to help viewers delve more fully into this historic art form.

Wallpaper border, “The Adventures of Don Quixote” panel from “The Adventures of Don Quixote” series, circa 1830. Mary B. Jackson Fund. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

When the Huards began to collect wallpapers in the 1920s, they did so gradually, approaching homeowners who they had heard were considering removing wallpaper, and working with antiques dealers. “The vast majority of the wallpapers found by the Huards came directly off the walls of homes in France,” Banas writes. They discovered wallpapers in abandoned homes and collected fragments which they archived with care. For many years they worked in partnership with the American interior decorator Nancy Vincent McClelland. “Alongside their business of selling wallpapers that they discovered, the Huards built their own collection of historical examples. Given the fragile nature of the papers, the collection has had limited public showing and the forthcoming exhibition marks the most in-depth examination of the works to date.”

Small format, block-printed sheets known as papier dominoté (domino paper) proved popular with its designs of flowers and foliage such as those produced by the Atelier Boulard. These sheets were used to cover books, to line drawers and to cover walls.

Over the next century, wallpaper creation in France became a bustling industry, with competition fueling products that were rich in color, texture and complexity. Manufacturers such as Zuber, Joseph Dufournand Jean-Baptiste Réveillon led the way. The elaborate process went like this: artists first created design drawings and applied color, whether watercolor, gouache or tempera.

Floral wallpaper by Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, 1790. Mary B. Jackson Fund. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

When the designer was pleased with the pattern, it would be transferred to transparent paper; then, with the aid of chalk and a steady hand, the pattern would be transposed onto the wooden block.

With wallpaper printing, the color itself was a gelatin-based paint called distemper (traditionally used for decorative work and theatrical scene painting) the carved blocks would be positioned in layers by means of small metal pins. The pins corresponded to the marks made by the printer on the edges of the paper roll and ensured perfect alignment of multiple layers.

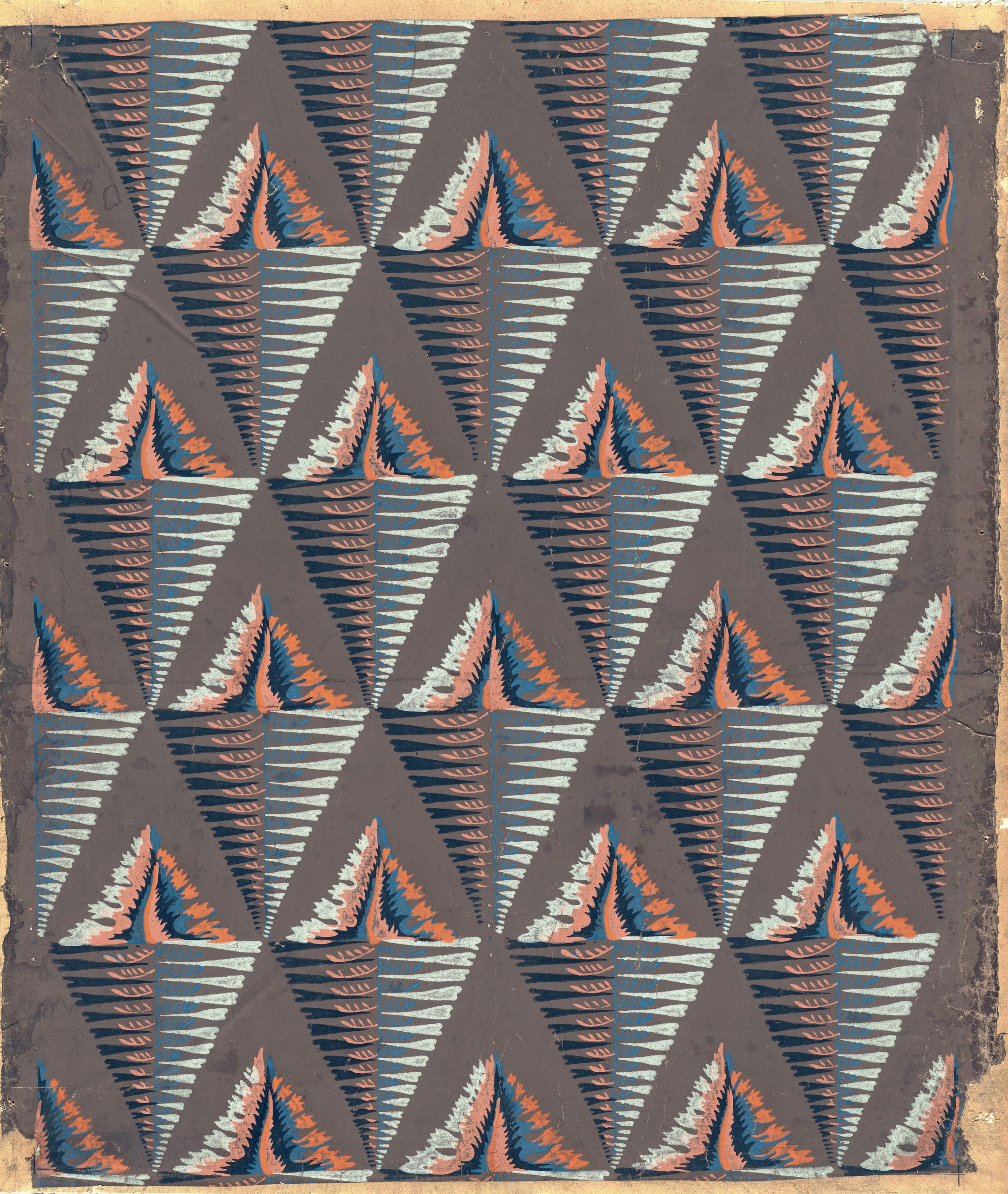

The end results could be stunning, with designs often drawn from Indian and Chinese textiles flowing into Mediterranean ports or the coveted hand-painted Chinese wallpapers made solely for export to Western markets.

For blocks intended to accommodate wallpaper-printing techniques, carvings needed to be much deeper than those made for other purposes: at least an eighth of an inch deeper. And each color in a wallpaper design required a separate carved block. A complex pattern could call for a few dozen blocks, and a large, wallpapered room might require that each block be printed hundreds of times.

Design for wallpaper border, French, 1830. Mary B. Jackson Fund. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

The RISD printmaking department head Andrew Raftery, whose essay appears in the show’s digital catalog, said recently that he has found it “highly ironic that histories of printmaking rarely recognize woodblock printed wallpapers for being some of the most ambitious and technically innovative prints ever made.” Raftery has created a course for the winter/spring semester, in which his design students will learn these ground-breaking techniques while working on a 100-year-old press installed in the gallery. He believes the intricacy of the process and the creativity of the multiple layers of artists and craftsmen will leave people with an appreciation for both their artistry and their openness to innovation.

Flocked papers were often reserved for borders, known as a soubassement, or dado, and were used to replicate the plush look of textiles. Flocking was wildly popular during this time and was used as a dynamic surface treatment on a variety of wallpapers, Raftery writes.

There are examples of the particular form of wallpaper known as a dessus de porte, or overdoor panel; and three valuable Chinese wallpapers featuring birds and flowers that were exclusively produced for export to Europe and America.

Banas approached the Adelphi Paper Hangings of Sharon Springs, N.Y., to replicate a wallpaper produced by the Paris-based manufacturer, Bon. The pattern, designed in 1799 by Bon, is a tour de force, reflecting “on the chiaroscuro woodcuts of Zanetti and the Nineteenth Century practice of pasting woodcuts on walls for decoration.” A video in the gallery walks the viewer through the process. People smitten with the pattern can place orders for their own homes.

Woodblock for wallpaper, late 1700s. Mary B.Jackson Fund. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

Raftery says his students are eager to learn the process and consider ways they might apply what they learn in their own printmaking practice. He adds that the energy, talent and enthusiasm of his RISD students are like that — “it’s what’s drawn me back to the classroom for 33 years.”

“Whether or not they knew it at the time, Charles and Frances Wilson Huard built a collection that would immortalize the extraordinary creative and technical skill of wallpaper production during this period in French history,” Banas writes.

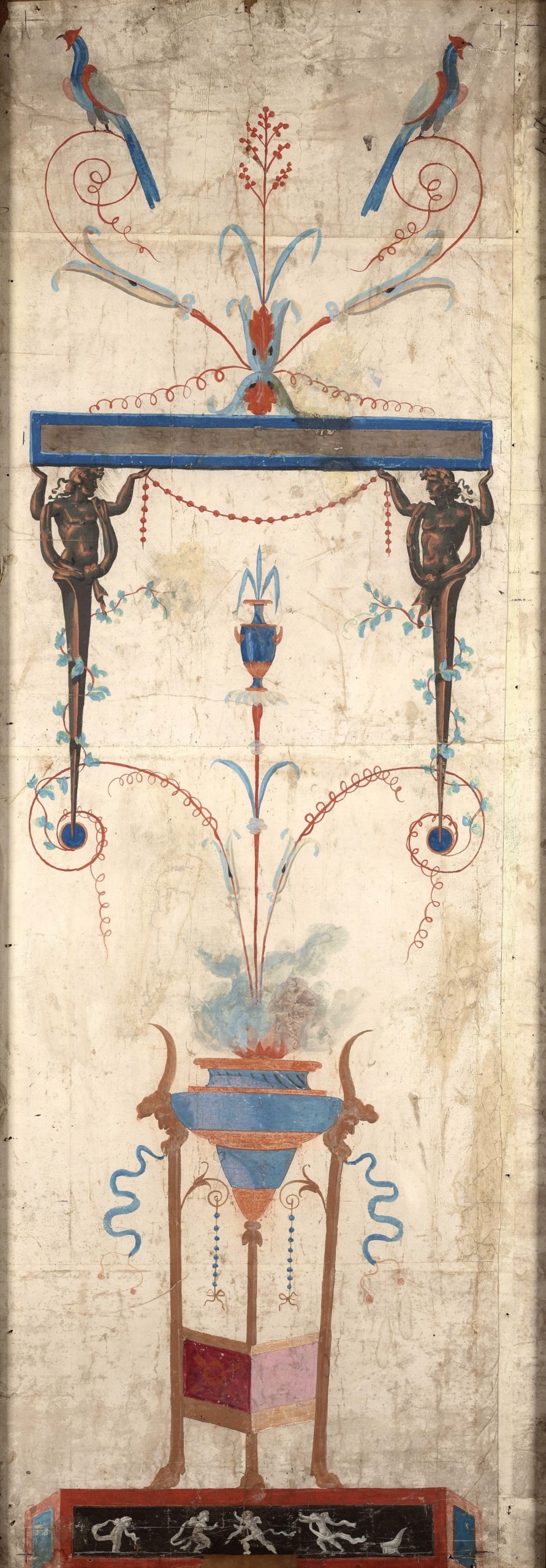

“There was a world of wallpapers beyond the repeats: singular panels made in imitation of paintings, architectural elements that could be cut out and arranged in a number of ways; and borders for all sizes for the top and bottom sections of walls.”

Bright colors and lively design elements were hallmarks of this era and some detective work from the Brown University geochemistry department has enabled RISD curators to analyze specific fragments, borders and sheets for the presence of inorganic metals, specifically heavy metals (including arsenic). RISD also enlisted the Somerville, Mass., paper conservation firm TKM, to undertake a restoration of Wallpaper with Muses and Arabesques — a project that called for removing soot most likely from the days of coal-burning furnaces and fireplaces that were used on a daily basis. TKM was also able to replace the original backing with acid-free materials.

Floral wallpaper from “The Five Senses” series by Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, 1790. Mary B. Jackson Fund. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

Among the astonishing works to see is Jean-Baptiste Reveillon’s “The Five Senses” (circa 1780), conceived at mural scale and created by Italian designer Pierre Cietti, and Joseph-Laurent Malaine’s (1745-1809) floral designs for Reveillon (circa 1790). Of the latter, Raftery says, “The sophisticated use of color in these designs is unprecedented in printmaking.”

Laurent’s work was truly “painting with woodblocks,” he added.

No wonder French painters of the time were anxious about the impact of fully pictorial wallpapers on their markets. Scenic wallpapers offered an alternative to murals, and smaller wallpaper panels were a versatile solution for overdoors, screens and other applications, he says. Wallpaper enabled prints to extend to room scale, to articulate architecture, and to penetrate daily life as a constant backdrop.

Raftery concludes that the history of printmaking has hitherto been incomplete without an accounting of wallpaper and its contribution to the techniques of relief and color printing. “The exhibition will open up new research methodologies using comparative impressions and technical analysis. Most importantly, it will provide impetus for the retrieval of the identities of anonymous designers, block cutters, and printers, bringing long overdue recognition of their brilliant contribution to visual culture, art and design.”

The Rhode Island School of Design Museum is at 20 North Main Street. For information, 401-454-6500 or www.risd.edu.