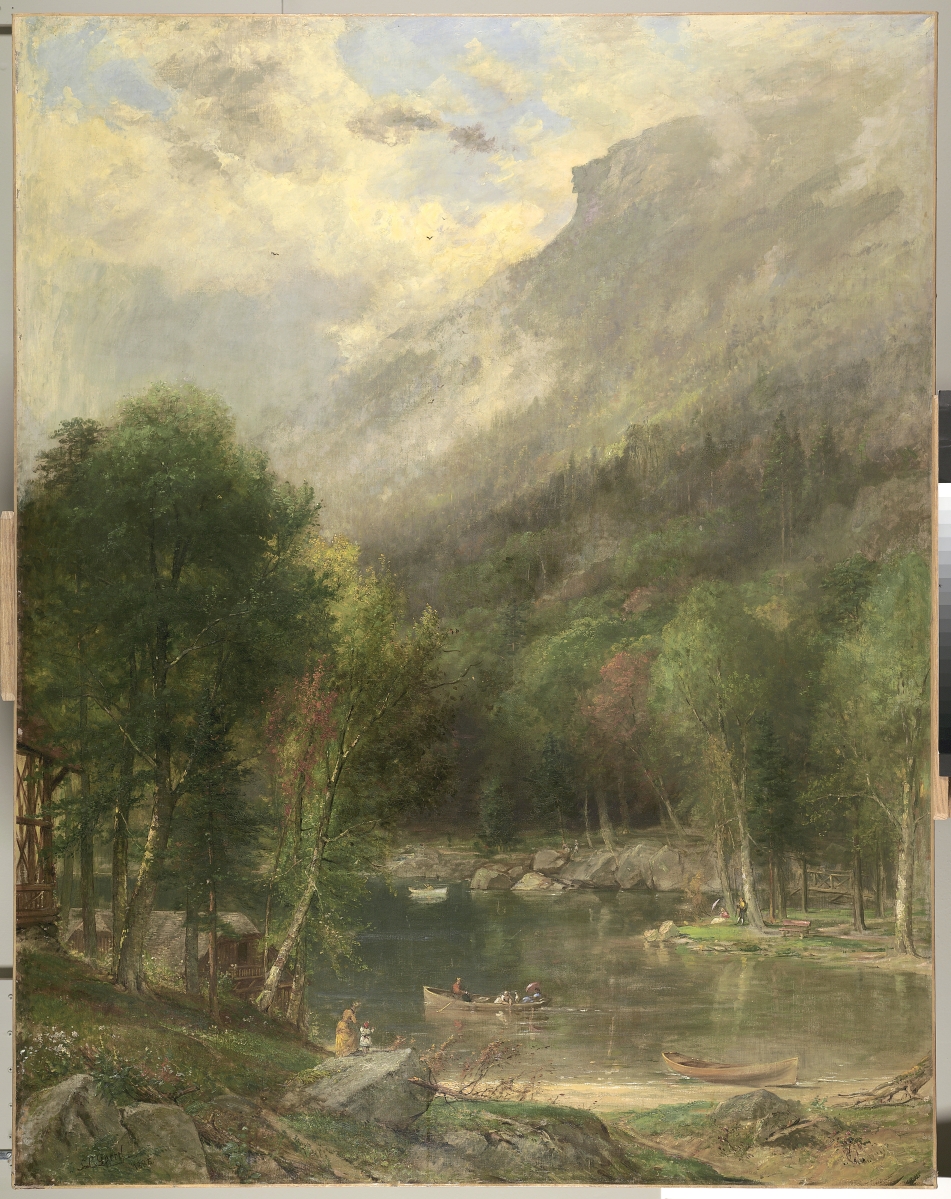

“Old Man of the Mountains near Profile House, White Mts” by Samuel L. Gerry (1813-1891), 1886, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Sullivan Museum and History Center of Norwich University, Northfield, Vt., gift of Mabelle Furst Greenleaf in memory of Charles H. Greenleaf.

By Rick Russack

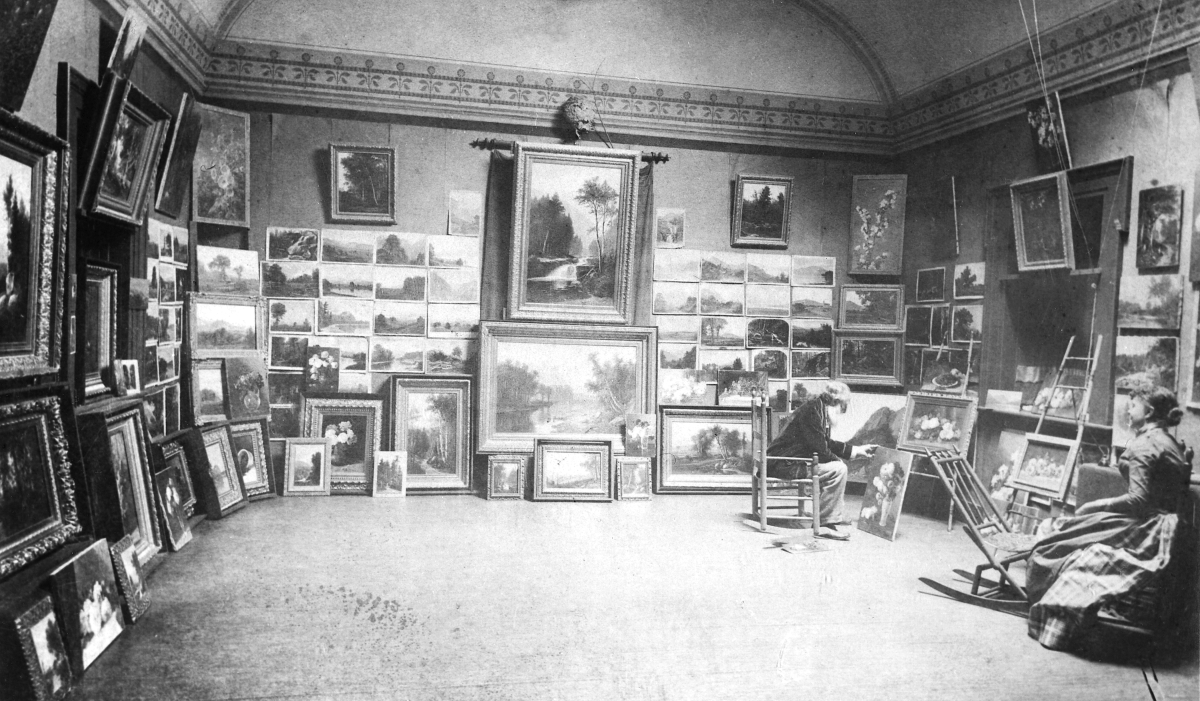

CONCORD, N.H. – The New Hampshire Historical Society has mounted an exhibition that includes almost 40 paintings by Samuel L. Gerry (1813-1891), a prolific and popular painter of New Hampshire’s White Mountain and Lakes Region scenery. From his home in Boston, Gerry, for decades starting the mid-1830s and continuing until just before his death, spent his summers in that area of New Hampshire. The 122-page, 2021 edition of Historical New Hampshire is entirely devoted to three essays discussing the life and works of Gerry, and some of his contemporaries. It serves as a catalog for the exhibition, “A Faithful Student of Nature: The Life and Art of Samuel L. Gerry,” and includes the results of several years of research by Charlie Vogel, his brother Allen, and others. The exhibition continues the society’s tradition of mounting exhibitions of the works of New Hampshire painters, especially White Mountain painters.

The New Hampshire Historical Society has extended the exhibition through August 13, thereby allowing those attending New Hampshire Antiques Week shows the opportunity to visit it. The exhibition is also online at the society’s website, www.exhibitions.nhhistory.org.

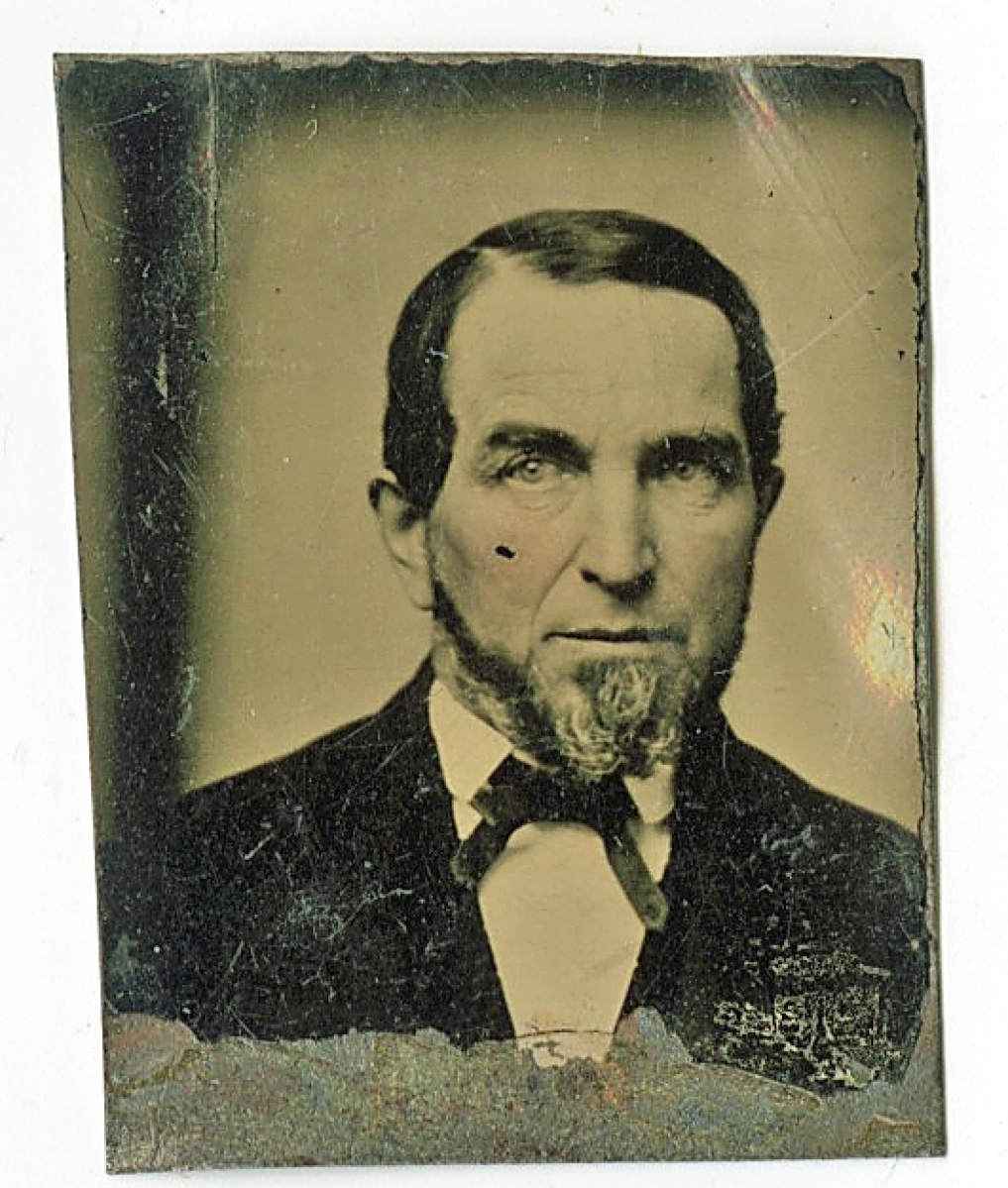

Samuel L. Gerry was a mostly self-taught artist who painted portraits (the demand for which, practically speaking for him, ended in the 1840s with the advent of photography), genre scenes and still life works, as well as the landscape scenes for which he became well-known. The first exhibit of his work was in 1833, when he showed an unidentified landscape at the Boston Athenaeum Art Gallery. He was 20 years old at the time. From 1834 to 1839, he and friend and artist James Burt ran an ornamental and sign painting business in Boston, and it was during this time, in 1835, that he made his first trip to the White Mountains. In 1836 he produced what is believed to be his first White Mountain painting, a scene on the Ellis River in Jackson, N.H. He also taught, wrote and lectured frequently on art.

Wesley Balla, director of collections & exhibitions, pauses for a moment with Samuel L. Gerry’s 1847 realistic painting of the village of Centre Harbor on Lake Winnipesaukee. At the time, this village was a jumping off point for travelers heading further north, into the White Mountains and the lakes area. —Rick Russack photo

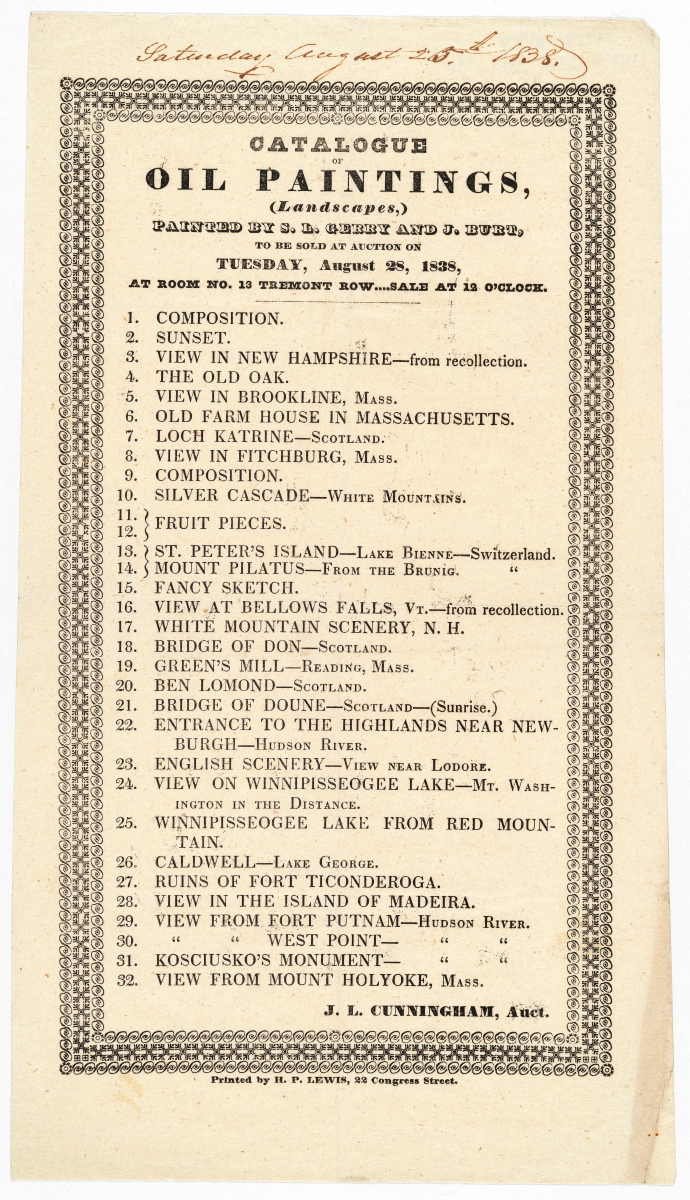

During the late 1830s and 1840s, artists sold many of their paintings through auctions, specifically to supplement their income. For the first time, in 1838, Gerry and his friend James Burt, sold 32 of their paintings at an auction in Boston, which was conducted by J.L. Cunningham, and which included some of Gerry’s White Mountain landscapes. Handbills such were circulated or posted to advertise upcoming sales. Other than Cunningham, auctioneers employed by Gerry included Williams & Everett, Leonard & Childs, Samuel Hatch, and Noyes & Blakeslee. In 1839, Gerry and Burt twice consigned paintings to auctions: 39 in March and another 45 in October. In 1862, a Boston auction house sold 70 of Gerry’s paintings. The same year, after a sale of 82 of Gerry’s paintings at the gallery of Williams & Everett, a Boston newspaper reported the results: $147.50 was the highest price, a total of $2,257.50 was realized and the average price was about $28. Selling at auction continued for several years, producing a steady stream of income for Gerry and the other artists participating. The largest number sold at a single auction was 121 in November 1875. This sale included works resulting from Gerry’s 1873-74 trip to Europe. Paintings were also sold directly from artists’ studios.

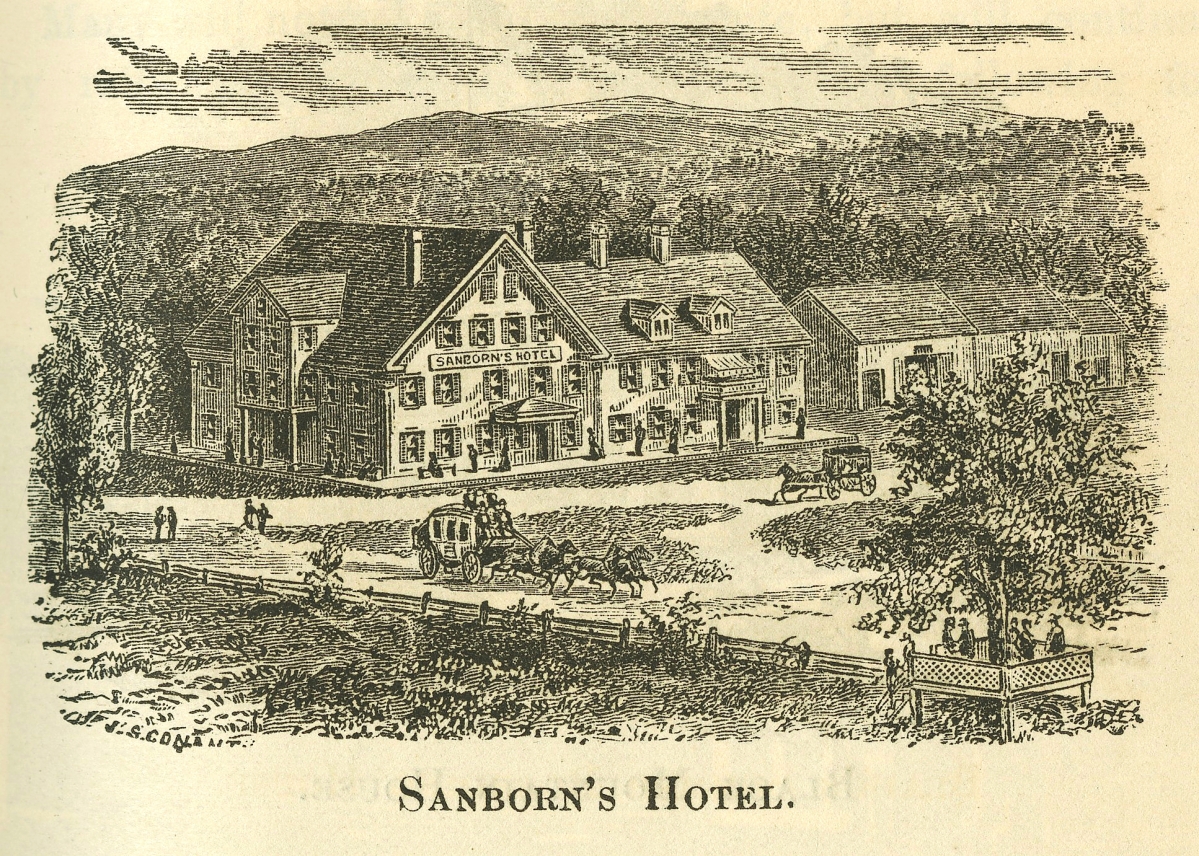

During his early summer trips to the mountains and lakes region, Gerry, along with other artists, boarded in any of the several small hotels in the area. Several of the White Mountain hotels had resident artists, with studios on hotel grounds, where sales were made directly to tourists and commissions might also be obtained. These hotels included the Crawford House, the Profile House, and the Glen House, among others. A favorite area for Gerry was North Conway, N.H., as was the area around West Campton, N.H., where he stayed at Sanborn’s Hotel for varying lengths of time for over 30 years, painting the scenery each of the locales provided.

“Tuckerman’s Ravine and Mount Washington” by Samuel L. Gerry (1813-1891), n.d, oil on canvas. Collection of P. Andrews and Linda H. McLane. At least five of Gerry’s paintings of this scene are known to survive today, making it one of his most common White Mountain subjects.

The term “painting” is somewhat misleading. His summers were spent sketching (The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has a collection of his sketches), and his paintings were produced in his Boston studio. For a few years, between 1853 and 1856, he owned a home in Meredith, N.H., within sight of Lake Winnipesauke. When he sold that house, he went back to staying at Sanborn’s Hotel in West Campton and often traveled to other areas, such as Franconia Notch, where he stayed at the Sunset Hill House in nearby Sugar Hill. Although the bulk of his output related to New Hampshire, he also spent time sketching in the Catskills, the Hudson River Valley and the coast of Maine; he also traveled to Europe at least once in 1849, and painted some scenes from that trip. In addition, he produced paintings in and around Boston.

Throughout his career, he experimented with different media, such as watercolors and charcoals later in life, both for sketching in the field and for finished work. Art critics, as well as art reports in the Boston press, were generally friendly to Gerry, with frequent complimentary comments about particular works, exhibitions and sales. It was not uncommon to read refrains about his “truthfulness to nature.”

At the end of the summer sketching seasons, Gerry returned to his Boston studio to transform the sketches into finished paintings, sometimes fulfilling commissions from those he met at the various hotels where he had stayed. His activities were often reported by art reporters for the Boston papers. He frequently participated in “artist’s receptions” in Boston, where his works were offered for sale, along with the works of others such as Benjamin Champney, another of the White Mountain painters whose home and studio were in North Conway. Exhibitions were numerous and frequent and he, along with others, sold many paintings through that type of venue in a variety of locations.

“Belle” by Samuel L. Gerry (1813-1891), probably 1880s, charcoal on paper. Collection of Charles and Gloria Vogel.

Commissions provided a steady stream of income. One of Gerry’s best known, and iconic works, was produced for Charles Greenleaf (1841-1924). In addition to owning the Hotel Vendome, one of Boston’s premier hotels, Greenleaf also owned one of the grand hotels in the White Mountains, the Profile House in Franconia Notch, site of one of the natural wonders of the age, the granite cliff ledges referred to as “The Old Man of the Mountain” because of its resemblance to a human face in profile. Greenleaf wanted two large paintings of the “Old Man” to hang in his Boston hotel. The larger of the two, 5 feet by 4 feet, was hung in the hotel’s main staircase and a smaller one is included in this exhibition. Gerry, again for Greenleaf, also did a painting of another natural wonder in Franconia Notch: the suspended boulder in the Flume. Neither of these geologic wonders exist today. Gerry stayed at the Profile House in Franconia Notch in 1879 and sketched in the vicinity in 1880 and 1881. He likely met Greenleaf at this time.

At the time these paintings were commissioned, it was widely known that both subjects were “at risk” due to the forces of nature, especially, the “Old Man.” Greenleaf particularly was concerned about the long-term fate of the “Old Man” and what he could do to extend its life. He paid for the best advice he could get on how to preserve it, installing iron cables, as recommended, to reduce the likelihood of, or at least postpone, its collapse. However, his efforts, and later ones by the state of New Hampshire, could not save it. On the night of May 3, 2003, it finally collapsed. And the suspended boulder in the Flume was washed away a year and a half after Gerry painted it.

Installation view of “A Faithful Student of Nature: The Life and Art of Samuel L. Gerry,” at the New Hampshire Historical Society through August 13. —Rick Russack photo

Throughout his entire career, Gerry taught art to numerous students, gave frequent lectures on art, and wrote extensively on the subject and about fellow artists. His attitude is reflected in a sentence he wrote in 1885, “what a world of pleasure art gives.”

The New Hampshire Historical Society, at 30 Park Street, is also currently exhibiting other parts of its collections, including Dunlap furniture, portraits of Daniel Webster and others, along with numerous other artifacts of New Hampshire history.

For information, 603-228-6688 or www.nhhistory.org.