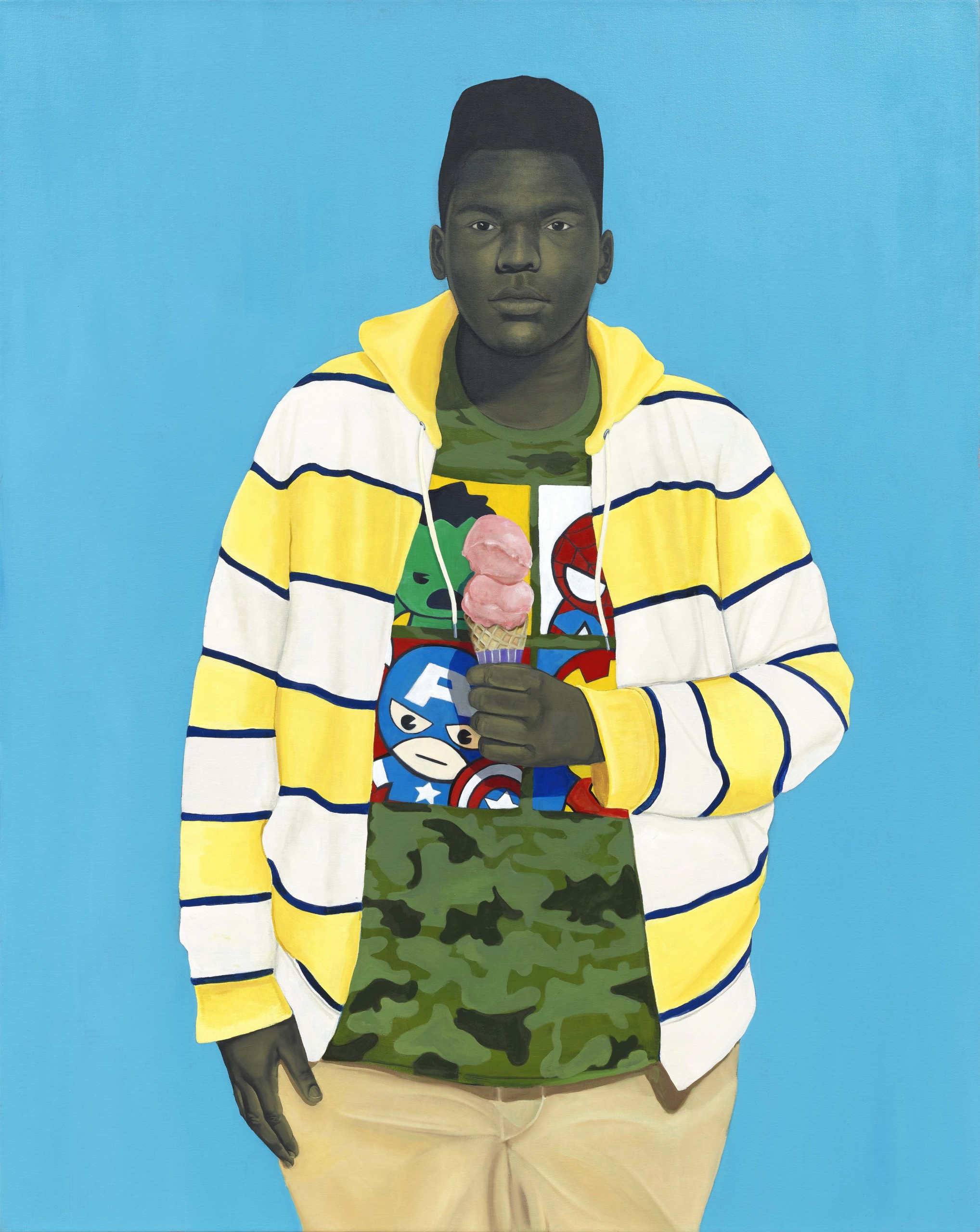

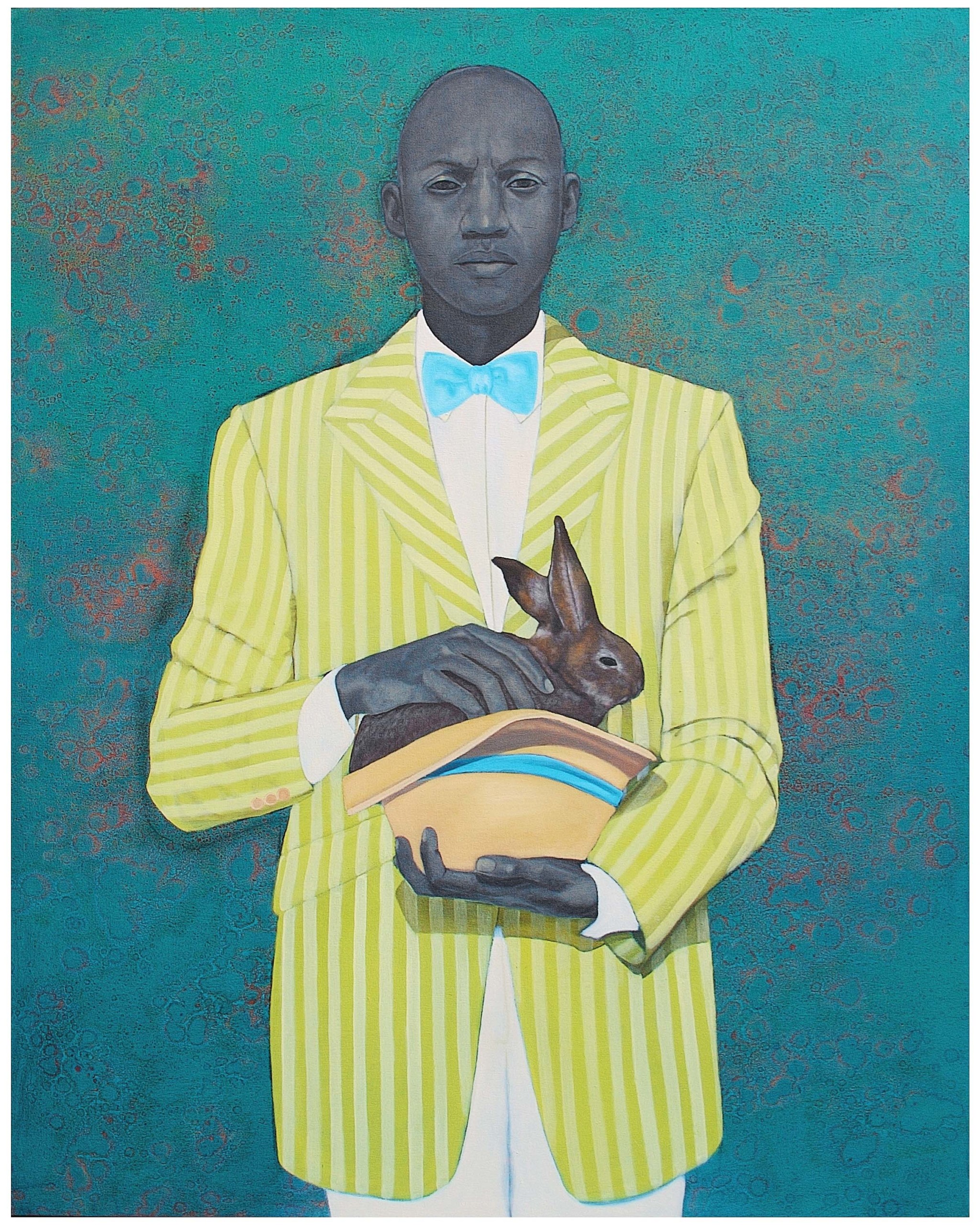

“What’s precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its presence (All American)” by Amy Sherald, 2017. Private collection, courtesy Monique Meloche Gallery; © Amy Sherald; photo: Joseph Hyde, courtesy the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIF. — It has only been a little more than six years, but it may feel like an age ago that many Americans first came to know the name Amy Sherald, painter of Michelle Obama’s official White House portrait, which caused a sensation when it went on public view at the National Portrait Gallery in 2018. Time has seemingly telescoped in the years since, marked by interleaving crises of the Covid-19 pandemic and political and social unrest. Both the Obama portrait and Sherald’s later portrait of Breonna Taylor — killed by police in 2020 — became visual touchstones for this turbulent moment in American history. So outsized was their impact, and the artist’s, that it hardly seems possible that “Amy Sherald: American Sublime,” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) through March 9, is only the artist’s first major solo museum exhibition.

In fact, the exhibition has been a long time coming, predating Sherald’s sudden global fame in 2018. Sarah Roberts, SFMOMA’s Andrew W. Mellon curator and the curator of the show, remembers meeting Sherald at an exhibition opening in Baltimore (where Sherald was then based) in 2016. Sherald later reminded Roberts that she had then expressed a hope that her first museum show would be at San Francisco — that it was her “dream spot.” Like many exhibition ideas optimistically voiced in the latter 2010s, little came of it as many museums shuffled their schedules and even went on long-term hiatus through the pandemic. But when Christopher Bedford, formerly of the Baltimore Museum of Art, became director of SFMOMA in 2022, the idea made the journey with him. Sherald and Roberts picked up their conversation again, not as if no time had elapsed, but rather with the knowledge that everything that had happened since that first conversation over hors-d’oeuvres had brought them to this moment.

Amy Sherald portrait; photo: Olivia Lifungula, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

The exhibition is very much a collaboration between artist and curator, Roberts confirms. The title is, in fact Sherald’s, taken from Elizabeth Alexander’s poem of the same title, which deals with Western expansion and the American landscape traditions that pictured it. “The idea of the sublime in art history has a very long complex history,” says Roberts. “What this means in this moment, for her work, is one line of thinking that informs the show.” The allusion to landscape painting is at first surprising, since Sherald’s large-scale figural works are, for the most part, anything but: many have entirely contextless backgrounds of a single vivid color (see “Bathers” from 2015, for instance).

What they share with Nineteenth Century American landscapes is instead an aspect of “world-making,” as both Roberts and Sherald, in a recent New York Times interview, put it. What is different from that earlier tradition is that Sherald builds worlds on her own terms, from memory, from imagination and from her deep engagement with art, film, poetry and history.

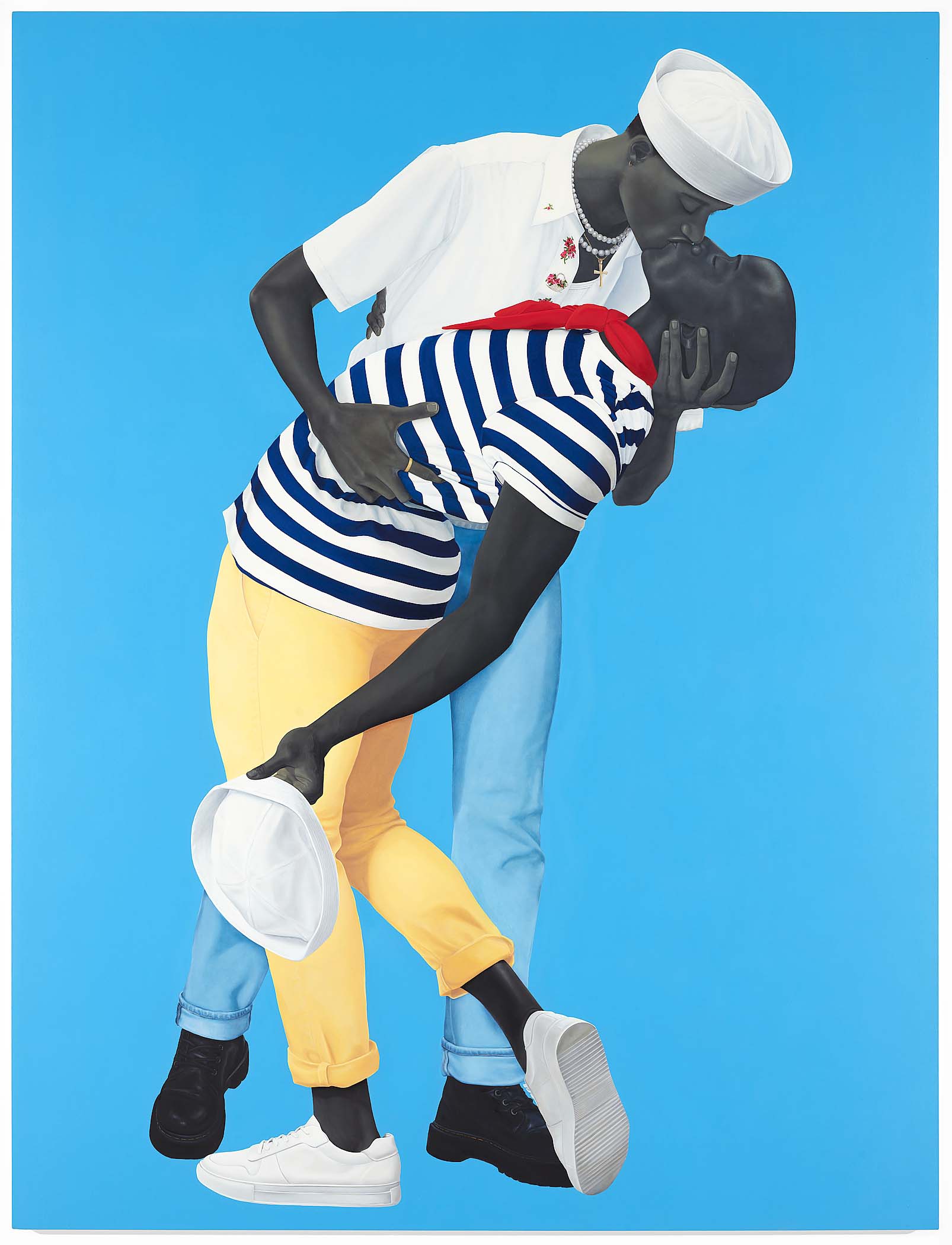

Take, for instance, “For Love, and For Country” (2002), a rethinking of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s famous 1945 photograph of a sailor stealing a kiss from a woman in Times Square on V-J Day. In Sherald’s version, the figure bent backward in the embrace is not a nurse struggling to keep her skirt from riding up but a man, using his free hand to grasp the same kind of sailor’s cap his lover wears. Both men, like all the people she paints, are Black. Sherald was “really struck by the kind of increasing rhetoric and violence against lesbian and gay members of the American citizenry,” says Roberts, “and wanted to make an image that really celebrated queer love and life… She was [also] thinking about the fact that there were Black sailors and soldiers who had fought and came home and didn’t get celebrated in Life magazine.” Here the blank blue backdrop — no buildings, no parade, no ticker tape — paradoxically provides the context. It is an imagination of a world where tenderness and passion and joy and triumph exist without fear or violence or war — nothing but blue skies, as it were.

“For Love, and for Country” by Amy Sherald, 2022. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase, by exchange, through a gift of Helen and Charles Schwab; © Amy Sherald; photo: Don Ross.

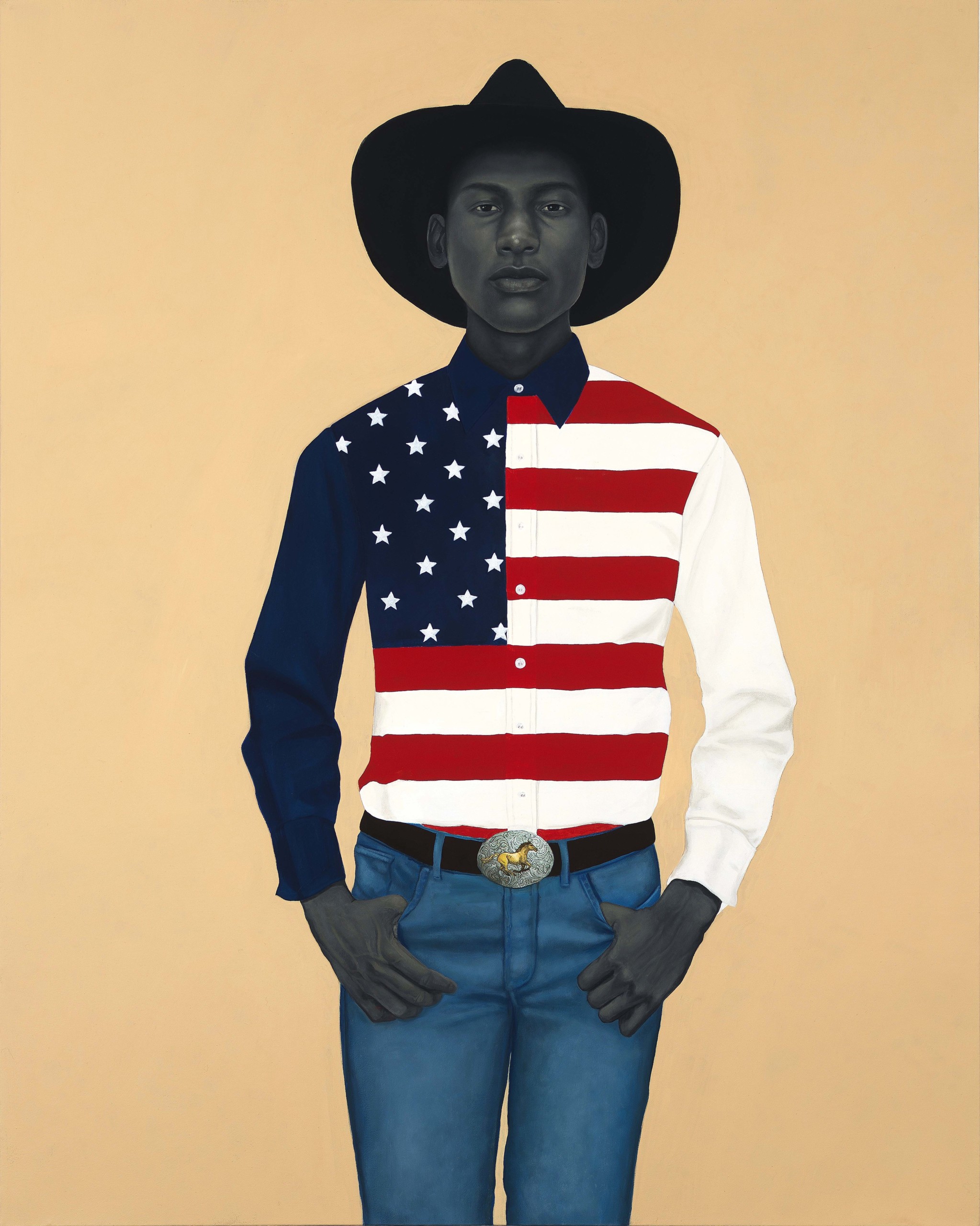

“For Love, and For Country” is in the first gallery of the exhibition, which, in Roberts’ words, “speaks to these historical ideas of who’s been considered American, what moments in American life have been captured in these iconic images and what’s been left out.” Others include a scene of two young girls holding hands and watching a rocket ship blast off; a frank image of a young Black man dressed in a black Stetson, jeans and an American-flag shirt; and a painting of a man sitting on a steel beam that is a direct allusion to the famous black-and-white photographs of construction workers eating their lunch 50 stories in the air while building New York’s skyscrapers. Sherald is “taking that image and turning it into something quite different,” Roberts says. “Putting a very pensive, sharply dressed, quiet, contemplative Black man in that position just pushes against the history that’s embodied in that picture. It asks us to stop and look at that man in a very different way than a lot of the imagery of Black Americans we are typically fed in the media.”

It is important to clarify that Sherald’s paintings are not, by and large, portraits — Michelle Obama and Breonna Taylor being the two exceptions. They are of real people in that she uses models and faithfully depicts their likenesses, but the paintings themselves are scenes from her own imaginings, and the models are chosen for their ability to embody that imagined world. These worlds — their subjects, allusions, compositions, astonishing colors — are arresting in any context, but she enhances their ability to make viewers stop in their tracks by hanging many of her paintings lower than is common practice in museums. The effect is that, broadly speaking, the eyes of the figure in the painting — the cowboy in his Stetson, for instance — are roughly aligned with the viewers, so that, Roberts says, “you have a person-to-person encounter.”

“Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama” by Amy Sherald, 2018. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; The National Portrait Gallery is grateful to the following lead donors for their support of the Obama portraits: Kate Capshaw and Steven Spielberg; Judith Kern and Kent Whealy; Tommie L. Pegues and Donald A. Capoccia; courtesy the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Equally unignorable, in all but her very earliest work, is her rendering of skin tones en grisaille, or shades of gray. Sherald was trained in this traditional technique, in which darks and lights are laid down before adding color, but she gradually came to prefer leaving her figures unadorned in this way. “It reminded her of black-and-white pictures of her family members she had looked at growing up,” Roberts explains. “Black-and-white photography cues a sense of history, a sense of a moment in time… It also connects for her with the importance of photography in African American culture, photography being the first means that Black people had to control their own image.”

Roberts traces Sherald’s interest in photography through to social media, which of course was a major tool of dissemination for the Michelle Obama and Breonna Taylor portraits. The common theme, she explains, is the idea of self-fashioning, another idea gleaned from the study of art history. “Social media has taught everyone how minute differences in facial expressions can be read differently; what it means to choose your clothes, to choose your body position in front of a camera,” Roberts says, connecting it to Sherald’s careful choices of pose, color, props and gesture. It’s world-making, in a way, and it goes some way to explain why we cannot stop looking at Sherald’s paintings.

The sections of the exhibition follow various interwoven threads throughout Sherald’s body of work. After the first gallery dealing with themes of American-ness, visitors experience “Precious Futures,” focusing on children and young adults. Along with “Precious Jewels by the Sea” (2019), with teenagers perched on each other’s shoulders at the beach, and “Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance)” (2014), inspired by Alice in Wonderland and the films of Tim Burton, is “The Boy with No Past” (2014), the title figure dressed flamboyantly in lemon-yellow trousers, an aqua-striped shirt and red-and-green Elton John style glasses. “It’s Amy imagining what it would be like for a young Black boy to grow up without having to think about all the history around race and the biases and preconceptions that people will inevitably come at him,” Roberts explains. “To just grow up completely free.”

“The Rabbit in the Hat” by Amy Sherald, 2009. Green Family Art Foundation, courtesy of Adam Green Art Advisory; © Amy Sherald; photo: Christina Hussey, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

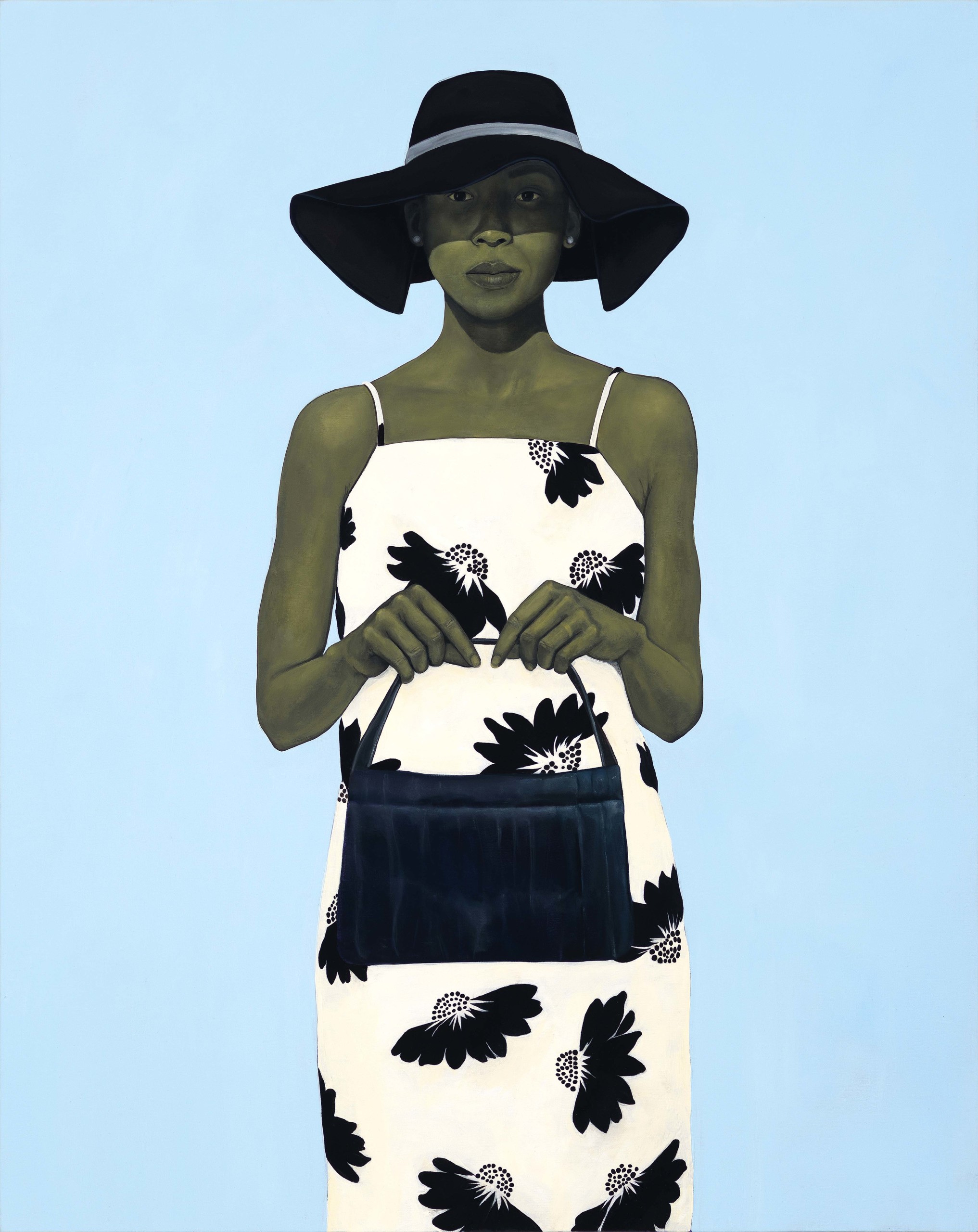

The section titled “An Inside and an Outside” teases apart W. E. B. Du Bois’s concept of double consciousness — the sense of having both an interior and an exterior life that, as a Black man, he found largely irreconcilable. Here are “She had an inside and an outside now, and suddenly she knew how not to mix them” (2018), its title taken from Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved and “What’s different about Alice is that she has the most incisive way of telling the truth” (2017), which casts the viewer as the subject by pointing a camera directly at them.

The Obama portrait has its own discrete space in the show (likely a crowd control measure), but “Breonna Taylor,” with the blessing of Taylor’s family, is in the section titled “The Girl Next Door.” The idea behind both this section of the show and of Sherald’s portrait that anchors it, Roberts explains, is of Taylor “being just like so many other young women we might come to know as friends or neighbors or coworkers.” The portrait came about as a commission for the cover of Vanity Fair magazine, and Sherald was motivated by a desire to make something that would explore the person she was and might have been, rather than the tragedy of her death. In the painting, Taylor wears the engagement ring her boyfriend had bought but not yet had the chance to give her; she wears a dress of “celestial” blue, as Roberts describes it, a hue that calls up an array of associations with princesses, angels and saints.

“Breonna Taylor” by Amy Sherald, 2020. The Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Ky., purchase made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation; and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC, purchase made possible by a gift from Kate Capshaw and Steven Spielberg/The Hearthland Foundation; © Amy Sherald; photo: Joseph Hyde, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The exhibition concludes by revisiting the idea of American-ness to examine what happens when inside and outside are finally unified, and what that looks like in American life. Two new paintings are being created for this section, although Roberts was reluctant to divulge anything about them when we spoke. (The New York Times piece teases a mixed-martial-arts athlete as well as a drag queen inspired by John Singer Sargent’s “Madame X” and the Statue of Liberty.) This is where we see “Listen, you a wonder, You a city of a woman. You got a geography of your own” (2016), its title taken from a Lucille Clifton poem called “What the Mirror Said.” It subverts the fairy-tale trope of the vain queen looking into her mirror and hearing harsh truths (also explored in an early work titled “The Fairest of the Not So Fair” [2008]); here the mirror provides a pep talk worthy of the stylish, self-assured woman looking back into it.

In sheer vibes as well as palette, “Listen, you a wonder” has much in common with the portrait of Michelle Obama, which along with “Breonna Taylor” is described throughout the exhibition materials as “arguably the most recognizable and impactful paintings made in the last 50 years.” It is a strong claim but an eminently supportable one that Roberts connects with Sherald’s sublime (if you will) union of skills: her “incredible talent for giving faces intelligence, humanity, emotion, psychology;” her brilliance as a colorist; and her intellectual capacity to retrieve and reconfigure associations from art, literature and American life that will be meaningful to her audiences — cowboy hats, rocket ships, beach umbrellas, patchwork skirts. The sense of timelessness she achieves in her paintings — no less of the future than of the past or present — makes them uniquely powerful images to meet, or perhaps transcend, this American moment.

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is at 151 Third Street. For additional information: www.sfmoma.org or 415-357-4000.