“Escutcheon of Charles V of Spain” by John Singer Sargent, 1912, watercolor over graphite on white wove paper, unframed overall: 12 by 18 inches. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1915 (15.142.11), ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NYC.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

WASHINGTON DC – Museumgoers might be forgiven for thinking they have seen just about all there is to see of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), the expatriate American painter who has never suffered for recognition. But what’s often forgotten about Sargent is that he cast an incredibly wide net – from Boston and New York to Montana, Florida, Paris, Rome, Corfu and the Middle East – and that he painted much more than just portraits of wealthy society types. Sargent was also deeply engaged with the broader world of aesthetics, an aspect of his career explored in a simultaneous exhibition, “Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass,” previously at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth and now at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut through February. His extended, repeated and far-ranging visits to Spain, and the unparalleled opportunity they provided to explore these interests, are the focus of “Sargent and Spain” at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC through January 2.

Curator Sarah Cash comes to the subject after years of engagement with other subgenres in Sargent’s career, including “Sargent and the Sea,” presented at the now-defunct Corcoran Gallery of Art in 2009-10, when Cash was a curator there. Her co-curator for that project was Richard Ormond, Sargent’s great-nephew and, with Elaine Kilmurray, co-author of the Sargent catalogue raisonné project (Yale University Press, 1998-present). Cash, Ormond and Kilmurray have worked closely together on “Sargent in Spain,” ensuring that this exhibition benefits fully from decades of scholarship that has unearthed little-known studies, works on paper and even, possibly, photographs by the artist that are either made in Spain or that reflect his fascination with all things Iberian.

Most of the photographs are ones that Sargent collected rather than made himself; they are primarily from a cache of material donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) by Sargent’s sisters shortly after his death in 1925. Despite this impressive pedigree, the photographs are understudied – both on their own merits and as aids for Sargent’s creative process. Many are on public view for the first time in this exhibition and reproduced unprecedentedly in the accompanying catalog (also from Yale). The ones from the V&A are “loose as opposed to bound in a scrapbook,” says Cash, depicting subjects as varied as “painting, sculpture, Spanish armor, landscape,” and more. There are also photos in a scrapbook Sargent kept from 1874 to 1880, covering his first trip to Spain in 1879. It is only open to one spread at a time in the show, but the other pages will be visible in digital form. “There are still other photos he collected that are in a scrapbook at Harvard that was too fragile to be in the exhibition, so we are displaying it virtually,” adds Cash.

“Spanish Roma Woman” by John Singer Sargent, circa 1879-82, oil on canvas, overall unframed: 29 by 23-5/8 inches. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of George A. Hearn, 1910 (10.64.10), ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NYC.

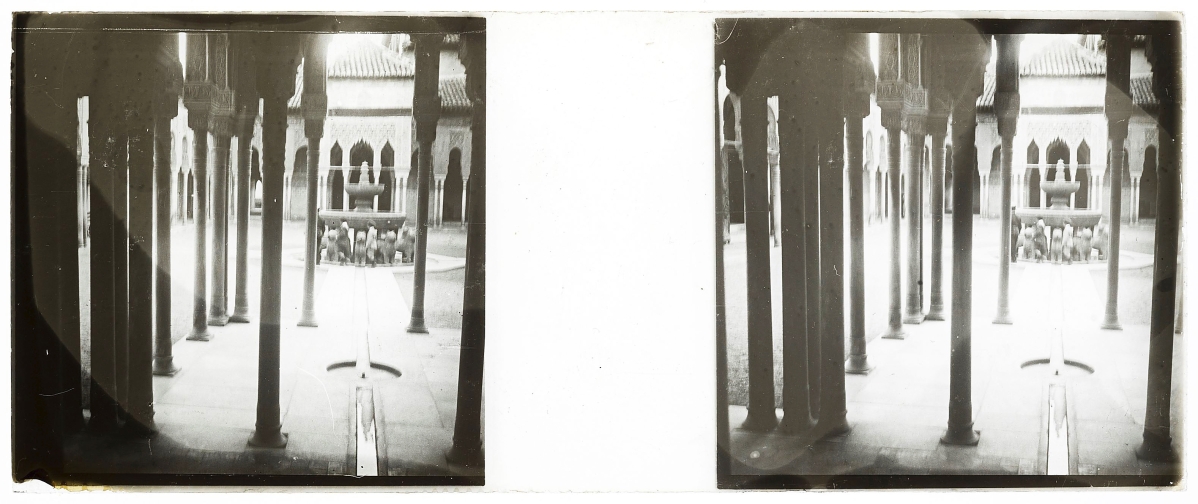

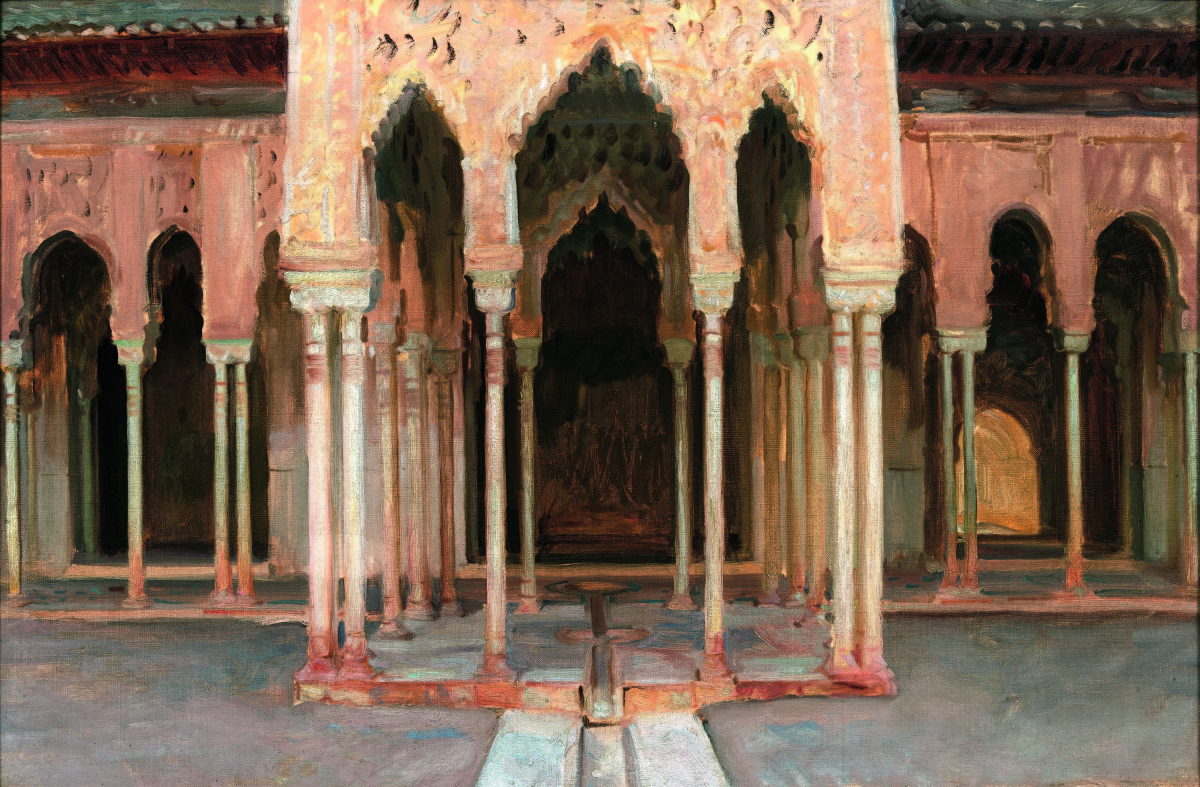

Cash notes how the photographs collectively convey Sargent’s deep interest in ornament. Snapshots he collected of Spanish landmarks found fresh expression, for instance, in works like “Alhambra, Patio de los Arrayanes” (1879), “A Marble Fountain at Aranjuez” (1912) and richly detailed watercolors of churches in Léon, Toledo, Majorca and Granada, among other places (thus also documenting his widespread travels throughout the Iberian Peninsula). There are instances in which a photograph’s association with a specific work is so pronounced that Cash is persuaded Sargent himself was the photographer: see, for instance, his painting “Alhambra, Patio de los Leones (Court of the Lions)” (1895) alongside a stereoscopic view of the same subject. Supporting this hypothesis is the fact that, by the turn of the century, photography had become eminently accessible to almost anyone who wanted to pick it up. At home or abroad, it was a fairly straightforward matter to produce one’s own stereoscopic views or “real-photo postcards,” another form of photography that Cash believes Sargent practiced.

Why the fascination with churches? As guest essayist Chloe Sharpe writes in Sensuality and Spirituality: Sargent’s Surprise to the Community in the exhibition catalog, “Sargent was not known to practice institutional religion,” and early in his career – his church views from Spain notwithstanding – he was also not particularly known for religious subjects. It was thus indeed somewhat surprising for him to have chosen “The Triumph of Religion” as the subject for an important commission to decorate the Boston Public Library with murals. Surely the choice had to do with the powerful impact that his 1879 trip to Spain had on his life and art. In addition to photographs, Sharpe notes, Sargent also collected purely populist forms of art deeply connected to Catholicism, like devotional reliefs of the Madonna standing on a crescent moon as the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. This precise motif found a manifestation in the Boston murals, in his depiction of Astarte, an Assyrian goddess of fertility, in a highly finished oil study. The mélange of religious traditions in Spain – where Catholicism dominated, then as now, but where many buildings and rituals bear marks of an Islamic or even pre-Christian past – thus provided a model for his mural project.

John Singer Sargent’s scrapbook, circa 1874-80, pencil and gouache on paper, closed: 12-7/8 by 19-3/8 inches. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs Frances Ormond, 1950 (50.130.154), ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NYC.

Initially planned only for the library’s Special Collections room, the mural commission expanded over the next nearly 30 years – until 1919 – the most active years of Sargent’s career. This meant that the murals were constantly on his mind throughout that time, including during his subsequent trips to Spain (in 1892, 1895, 1903, 1908 and 1912), and helps to explain the array of his aesthetic interests while there. There are studies of Spanish churches, crucifixes, Madonnas and saints, yes, but there are also remarkably detailed watercolors like “Well Head with Kufic Inscription” (1879) and “Escutcheon of Charles V of Spain” (1912), as well as his many studies of Islamic architecture and design in Córdoba, at the Alhambra, and elsewhere. He was consciously gathering ideas not just for mural subjects but for the visual framework in which they would exist. “Ornament was a big part of the Boston Public library murals,” says Cash, connecting Sargent’s task there to the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk, a German word that describes a kind of all-encompassing art form. “He was working with architects on how to design the surrounds for the murals, the wall sconces; he was doing everything.”

Even so, the murals were not his only consideration during his Spanish travels. He was also drawn to the nation’s varied landscapes and vegetation – for example, in a particularly lush series of oils from Majorca – as well as its people and local customs. He was enthralled with flamenco, a dance tradition of southern Spain that is the subject of guest essayist Nancy G. Heller’s essay in the catalog. His most famous work on this subject – as well as, Heller writes, “the best-known and most-powerful image of flamenco ever painted, by anyone” – is “El Jaleo” (1882; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum), unfortunately not available for the exhibition due to the Gardner’s famously strict loan policy. There are other delights here, however, including a dizzying array of studies for “El Jaleo” that show him working out that insouciant flip of the dancer’s hand as well as the faces and costumes of those who watch and accompany her.

“El Jaleo” was far from the only magnificent painting Sargent made of Spanish dance: here, too, are “The Spanish Dance” (circa 1879-82), possibly inspired by the same performance or at least the same venue; and two memorable portraits of the celebrity dancer Carmencita, both made in the same year (1890) but with entirely different approaches. In the first, the dancer stands as still and self-possessed as a Spanish hidalgo, her ebullient costume set against an undefined, dun-colored background borrowed directly from Diego Velázquez, whose works Sargent had copied in the Prado in Madrid. In the second, she dances – skirts swishing and fringe flying. Like “El Jaleo,” this work engages the senses well beyond vision: viewers can almost hear the music Carmencita dances to and the tap of her heels on the floor; there is a sense of heavy perfume, perhaps smoke and liquor; the rustle of fabric seems tactile as well as audible.

“Well Head with Kufic Inscription” by John Singer Sargent, circa 1879, watercolor over graphite on paper, unframed overall unframed 12¾ by 9½ inches. Private collection, courtesy Christies, New York City, Scan: Prudence Cuming Fine Art Photography.

The paintings of Carmencita were not made in Spain; she was traveling in the United States at the time and performing a kind of pastiche of traditional Spanish dance and ballet. But Sargent’s interest in flamenco was authentic and extended beyond the performance to the performers themselves, mostly Romani or “Roma” people from southern Spain. Roma were then a much-maligned minority – they continue to suffer persecution today – and not necessarily an obvious subject for an artist of Sargent’s caliber. His paintings of them, as dancers and everyday people (“Spanish Roma Woman,” circa 1879-82; “Spanish Roma Dwelling,” 1912), are certainly different from his contemporaneous portraits of American robber barons and British aristocrats; his famous talent for flattery is largely absent here, and there is no attempt to depict them as pleasingly decorative “peasants,” as some of his contemporaries might. And yet the paintings seem candid rather than callous. Sargent rarely painting anything that wasn’t equally beautiful and interesting, and his paintings of the Roma community are no exception.

Beyond the discoveries related to the photographs, this exhibition represents another significant contribution to Sargent scholarship. For the first time, members of the Spanish Roma community were brought in as consultants to interpret the works that depict their community; members of that advisory group ended up writing several of the texts that appear on the gallery walls, another first for the National Gallery. The terminology was important, notes Cash, explaining that the phrase “Spanish Roma” was a careful group decision. “We don’t have any evidence that Sargent ever called anyone a gypsy, but we knew in 2022 we weren’t going to do that,” she explains. That effort extended beyond the exhibition itself to the established scholarship on individual works; Cash and her fellow curators contacted the owners of works to ask for permission to change titles to swap out the outdated term. Certainly, it was useful to this effort to have the imprimatur of the catalogue raisonné, led by Ormond and Kilmurray, who were able to explain that titles are often assigned by dealers or past owners rather than the artist himself. The exhibition and publication offer evidence that such a seemingly small change can have a significant and meaningful impact.

Visitors to the exhibition in Washington may find themselves suddenly struck with a desire to visit Boston, home to not only the library murals and “El Jaleo” but also “The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit” (1882; Museum of Fine Arts), famously inspired by Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” (1656), which Sargent sketched at the Prado (in the Met scrapbook). “Daughters” is another painting that is jealously guarded by its home institution and almost never lent. Visitors expect it to be there and have come to identify it closely with the MFA, just like “El Jaleo” with the Gardner. This is a testament to the power and appeal of Sargent’s works from Spain, their emotional and sensory pull, and the thrill of confronting them face to face – an opportunity abundantly supplied by this landmark exhibition at the National Gallery of Art.

The National Gallery of Art is on the National Mall between Third and Ninth Streets on Constitution Avenue. For more information: www.nga.gov or 202-737-4215.