By Kristin Nord

WASHINGTON, DC – When Crawford Alexander Mann III, curator of prints and drawings at the Smithsonian Museum of Art, began work on “Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and The Magic of Murano,” he turned to new scholarship to expand upon this venerable story.

For centuries, Italian ambassador Armando Varricchio writes in the exhibition catalog, Venice had overseen a thriving maritime glassmaking empire, and the island of Murano in the Venice lagoon had played a major role, drawing upon the art of Southwestern Asia and adapting it for specific markets.

But this history was interrupted by Austrian occupation; it was only in the mid-Nineteenth Century, with Italian unification after 70 years of Austrian control, that a glassmaking revival got underway.

Antonio Salviati (1816-1890) would play a major role in Murano’s renaissance by establishing a small firm to assist with the restoration of Italy’s treasured mosaics. In time Salviati’s operation would mushroom into a constellation of companies that restored and produced elaborate mosaics and hand-blown art glass for export.

By the turn of the Twentieth Century, Venice had reclaimed its mantle as a major glassmaking region, with new generations of Murano artisans creating complex and colorful goblets and bowls based upon historic forms and techniques.

The revitalized industry was fueled by the virtuosity of its craftsmen who elevated their objects from souvenirs to museum-quality objects. This exhibition explores this cultural period and the paintings, etchings and drawings it inspired.

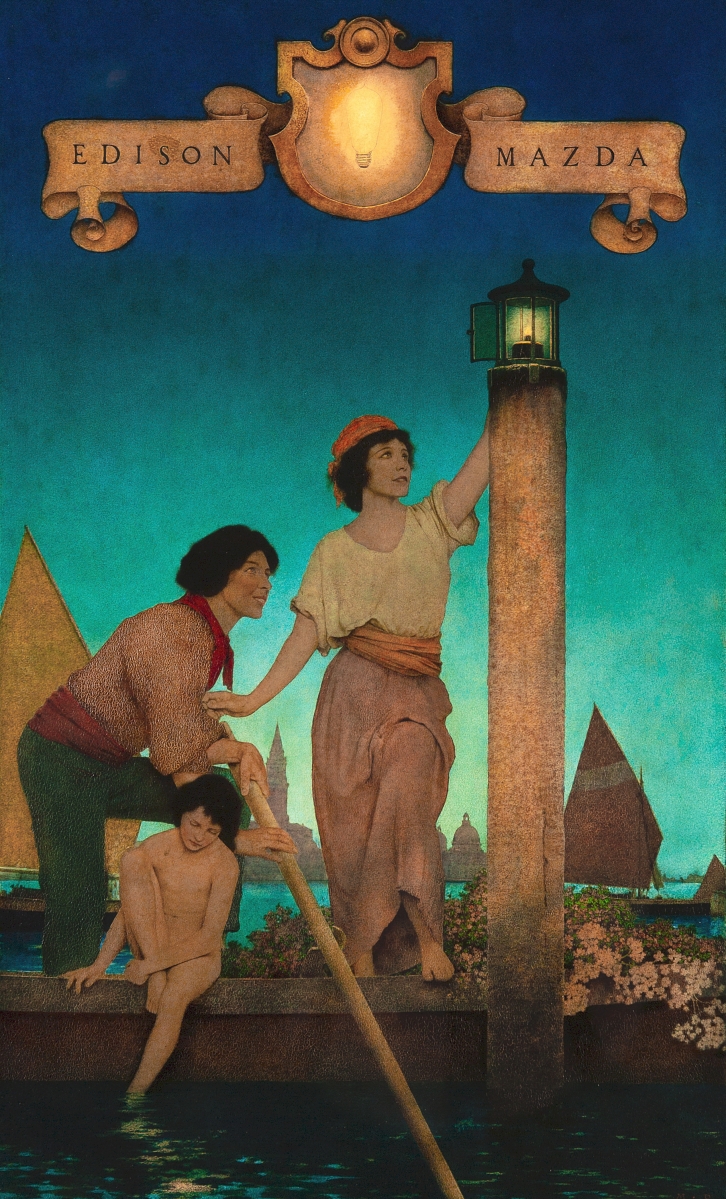

Installation image, “Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano,” 2021. Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; photo by Albert Ting.

Between 1860 and 1915, the revival of Murano’s renowned glassmaking industry was matched by a surge in American tourism. Many American visitors visited the glass factories of Murano during their travels, enjoying access to an industry known for its secretive practices and closely guarded formulas. A few wealthy Americans began to amass major collections, seeing in them the ideas touted by the Anglo-American Aesthetic Movement. It was a time when arbiters of taste promulgated the idea that domestic interiors could serve as compositions in their own right – artfully coordinated and arranged just as a painter might choose and place colors and forms on a canvas. Domestic interiors might display objects “for art’s sake”; and hand-blown art glass works had the capacity to dazzle and enchant.

Anyone who has watched a talented glass artisan at work is spellbound by the transformation of simple elements into objects of refinement. These luxury objects were appreciated for both their beauty and their difficulty of creation. Salviati artisans undertook the restoration of mosaics in Venice’s St Mark’s Basilica, and then took on projects for modern churches and other institutions, including London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Murano artisans thrived in an environment in which they were encouraged to experiment and innovate.

“Thanks to Salviati’s relentless pursuit of technical perfection and the young glassblower’s highly competitive spirit, they were able to transcend the technical skills of their ancestors and achieve an absolute mastery of their medium in a remarkably short time,” Sheldon Barr writes in an essay in the exhibition catalog. By 1890, he adds, the author Madeline W. Wallace-Dunlop was pronouncing that “Venetian blown glass is now as nearly perfect as anything human can be.”

The magic of transforming modest materials into hand-blown marvels and stunning mosaics inspired many visiting artists to these real or imagined fiery spectacles in works such as Charles Frederic Ulrich’s “Glass Blowers of Murano,” a painting also made into a photogravure.

Visual artists, including John Singer Sargent and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, also were drawn into the region’s light, architecture and inherent drama. In this show we see the ways in which American artists and writers took delight in Venice and Murano, capturing street scenes and seascapes as well as vignettes of Murano’s glass artisans.

Mann has selected 140 works to explore this story and delves into the lives of both artists and prominent collectors who put Murano glass, mosaics, lace and jewelry at the forefront.

Installation image, “Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano,” 2021. Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; photo by Albert Ting.

He introduces us to major collectors: Jane Elizabeth Lathrop Stanford (1828-1905), whose private museum in Palo Alto, Calif., houses one of the most important Venetian glass collections in the country; and Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924), whose interest in Venice was likely sparked by a meeting with Henry James during an 1879 tour of London and Paris. Her idea, to bring Venice to Boston, came to fruition when the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum opened its doors in 1903. Mann also drew from the collections of prominent Smithsonian patron John Gellatly (1853-1931) and John Jackson Jarves (1818-1888), whose collection resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While most Americans encountered these works through articles in popular magazines, department store displays or presentations at world’s fairs, a number of wealthy American tourists encountered these objects in visits to Venice in the 1870s and 1880s, as the region’s fortunes soared. American expatriates, visual artists and writers were drawn to Venice as well.

Among them was Whistler, whose prodigiously creative 14-month stay in Venice yielded at least 50 etchings, more than 90 pastel drawings and three oil paintings. Whistler’s sojourn coincided with the presence of a circle of Munich-trained American artists led by Frank Duveneck (1848-1919) who became known for his etchings and what he called his “Italian-style” paintings.

Whistler (1834-1903) had been reared in St Petersburg, Russia, where his father worked as an engineer overseeing the construction of a rail line to Moscow. He’d pursued his early art studies at the US Military Academy at West Point, later joining the drawing unit of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey. Some two decades later, following a successful but financially ruinous lawsuit against John Ruskin, it was two sets of etchings of Vienna that he produced for the Fine Art Society of London that helped him turn his fortunes around.

For Sargent (1856-1925), who was born in Italy and lived abroad throughout his life, Venice loomed large. He was already an accomplished artist by the time he settled into quarters on St Mark’s Square, just steps away from the Basilica. He took a studio in a building where Whistler had worked just a year before. It was here that he took to painting narrow side streets and squares and the people who occupied them. He returned again and again, capturing scenes in watercolors of architectural views.

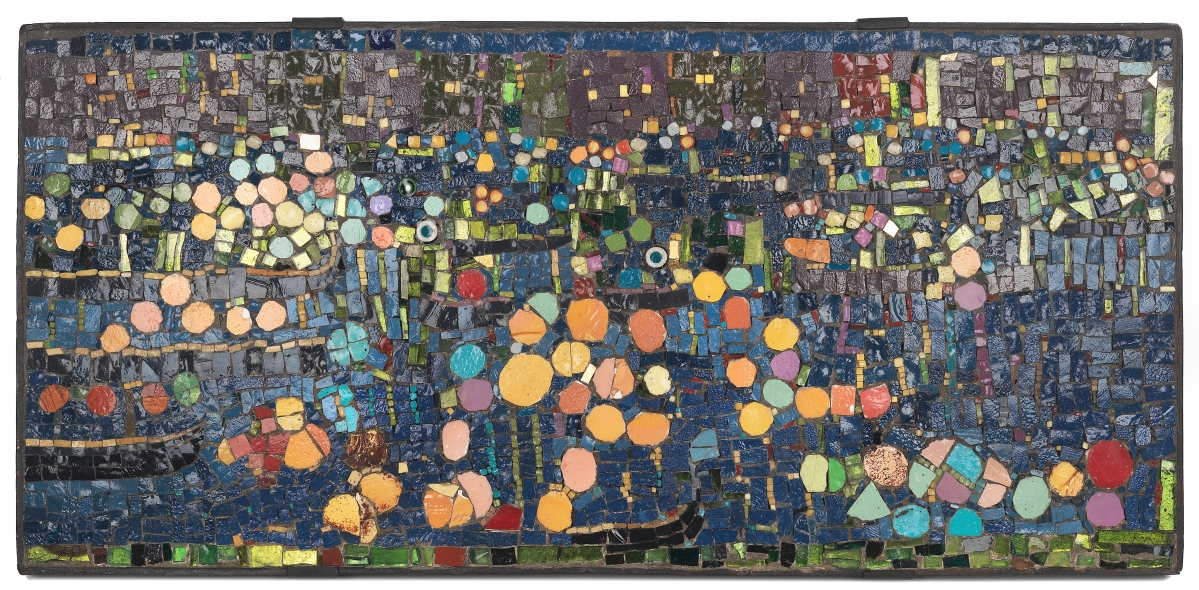

Maurice Prendergast (1858-1924) spent about 18 months in Italy from 1898 to 1899. According to his friend and fellow artist Charles Hovey Pepper, “He soaked up Venice. Then saturated, he worked.” Prendergast sought to represent the newly unified Italy in a style that he adapted to make his own. Fascinated by the fixed repetition of tesserae-like shapes and colors he encountered in glass mosaics, he produced some 50 watercolors, oil paintings and monotypes inspired by his Venetian visits, and earned recognition as an American modernist.

Yet by the early Twentieth Century, the popularity and prestige of revival glass was on the wane. New mechanical advances in glassmaking challenged the Venetian tradition of creating ornate and singular handcrafted artifacts; and American designers Louis Comfort Tiffany and Frederick Carder were eating into the top-tier art glass market. Aesthetic tastes had shifted, and objects with their historical references and extreme technical complexity were no longer valued. These shifts in taste would ultimately denigrate Venetian revival glass and relegate its once-prized objects to attics and museum vaults.

“A Venetian Woman” by John Singer Sargent, 1882. Oil on canvas. Cincinnati Art Museum, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1972.37.

In addition to rare etchings by Whistler and significant paintings by Sargent, are works by other leading American visual artists of the period. More than one quarter of the objects are drawn from the Smithsonian’s collection, with loans from an additional 45 prestigious museums and private collections. Mann has taken care as well to showcase the work of several women artists, including two of Mabel Pugh’s (1891-1986) linoleum block prints, and pays particular attention to both American collectors Stanford and Gardner, who were at the forefront of reviving and sustaining Venice’s glass, bead and lace industries.

There are glass works by the legendary Seguso and Barovier families, a glass mosaic portrait of Abraham Lincoln clearly aimed at the American consumer, Sargent etchings and luminous portraits; and rather dizzying examples of blown and hot worked glass, including a goblet with swans and an initial “s” stem, dated circa 1870, and a tour de force fish and eel vase, attributed to Vittorio Zanetti, circa 1890, from the Gellatly collection.

Mann hopes audiences will come away from the exhibit with an appreciation of the impact this period of cultural history had on American art making and collecting. In many ways, it was profound.

“Thanks to years of research, we present an accurate reconstruction of the tastes of these travelers using masterpieces of glassware and fine art that they purchased more than a century ago,” he said.

After closing in Washington. DC, the exhibition will travel to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, and the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Conn. An accompanying exhibition, “New Glass Now,” is on view at the Renwick Gallery, the Smithsonian’s branch for contemporary craft, through March 6.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum is at the corner of 8th and G Streets, NW. For information, https://americanart.si.edu or 202-633-1000.