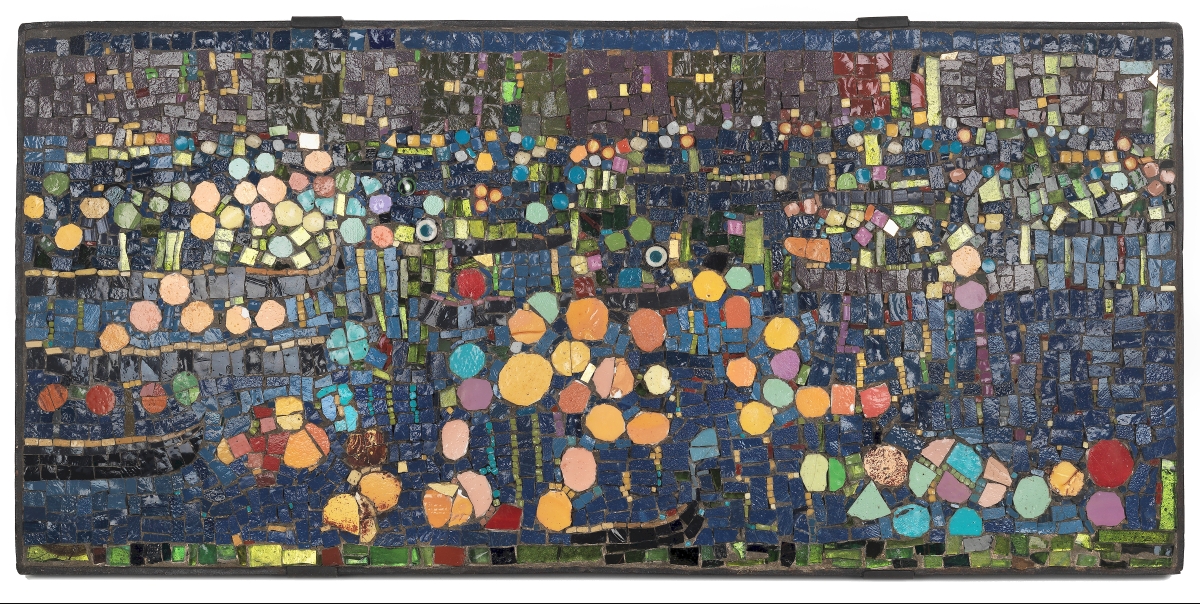

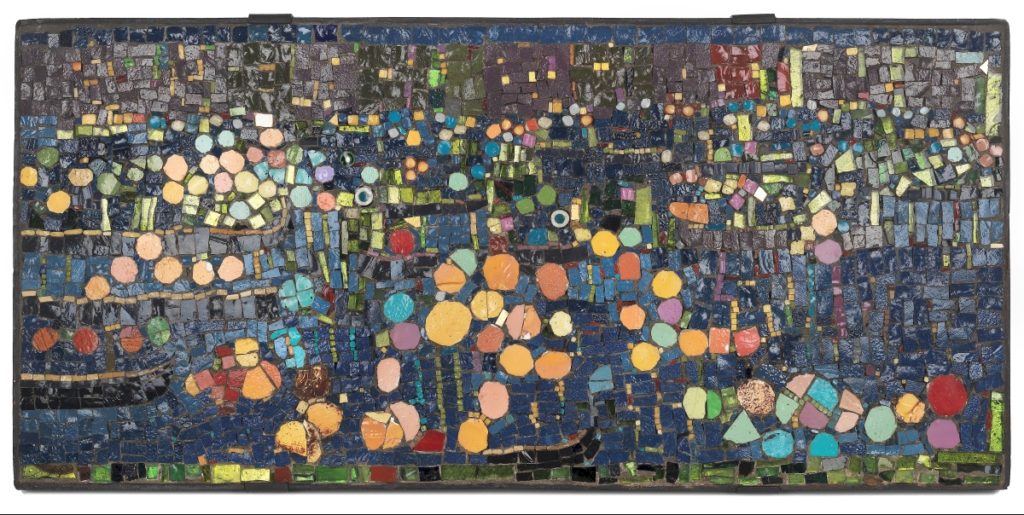

“Fiesta Grand Canal, Venice” by Maurice Brazil Prendergast, circa 1899. Glass and ceramic mosaic tiles in plaster, 11 by 23 inches. Williams College Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs Charles Prendergast, 95.4.79. The Impressionist’s experimental mosaic epitomizes the intersection of American art and Venetian glass.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

FORT WORTH, TEXAS – Venice, perpetual arts mecca, right? Well, maybe not. As “Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano” makes clear, the history of the Queen of the Adriatic is far more complicated. Chic Venice, now so popular that tourism threatens its very infrastructure, was passed over by international travelers only 150 years ago. This exhibition and catalog address the role Americans played in helping to “construct” the arts capital and, in turn, the impression Venetian arts and design made upon American artists and collectors during the era 1870 to 1920.

Organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), the exhibition can be seen at Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art through September 11 before moving to Mystic Seaport later in the year. Curator Crawford Alexander Mann III, who has since joined the staff of Savannah’s Telfair Museums, assembled more than 140 objects for his imaginative, ambitious presentation exploring the interplay of fine, decorative and commercial art.

In this tribute to the City of Bridges, archetypal vistas in oils incorporating water, sky and structures are complemented by romantic vignettes of the labyrinthine city captured by James McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent and other American artists. These more intimate views show Venetians on and near canals as well as in piazzas, backstreets, bars, homes and workshops. Next come wonders in glass and lace from the islands of Murano and Burano, art souvenirs of the highest order aimed at deep-pocketed visitors. Following that grand parade comes discussion of the ways wealthy American tourist-collectors incorporated such trophies into domestic décor and public exhibitions during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries.

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln by Enrico Podio, 1866. Glass mosaic tiles, 22¾ by 20¼ inches. US Senate Collection. Antonio Salviati presented this depiction of the recently assassinated president to the US government in hopes of securing a commission for architectural mosaic decorations.

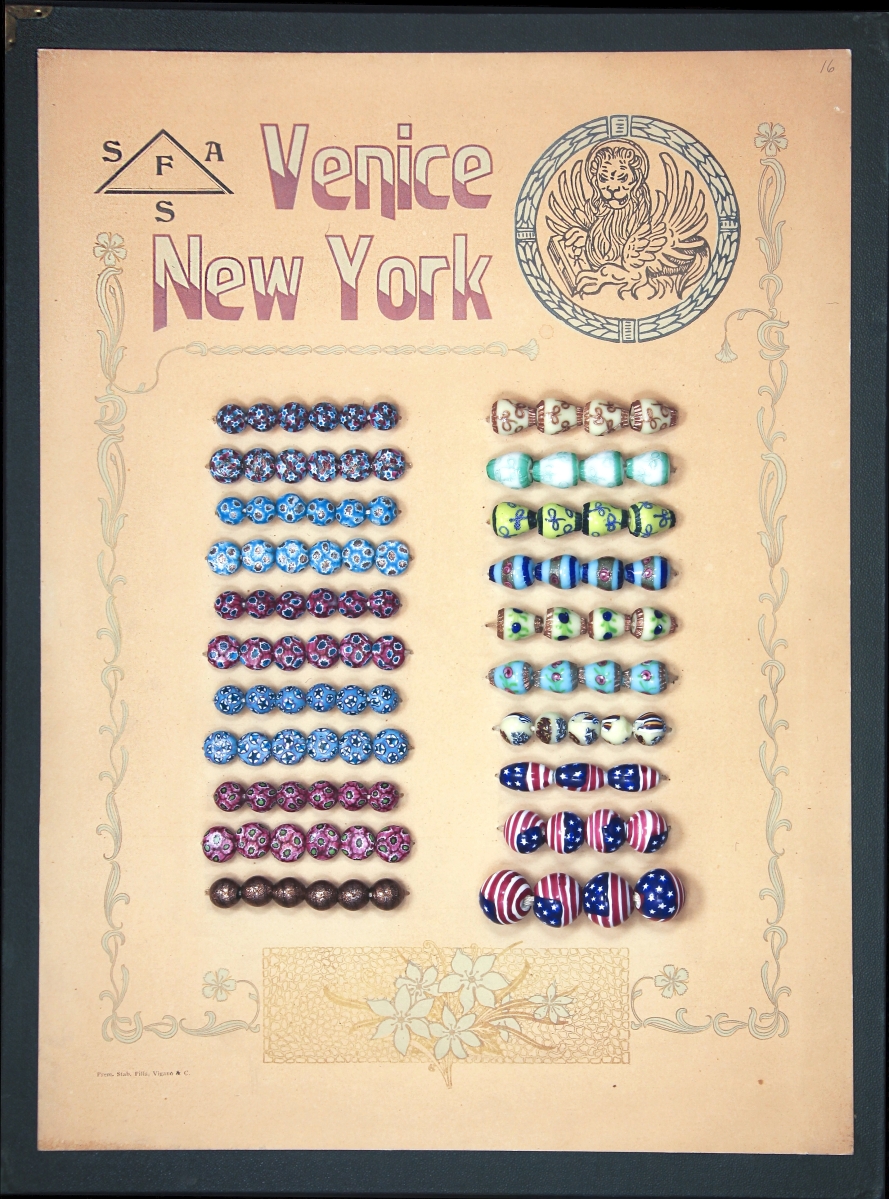

A bit of background on the history of Venice is in order. A gateway for travelers and luxury goods moving between Europe and Asia, the resplendent mercantile center was long tied to the Byzantine and Turkish Empires. It turned out top-quality table glass, particularly sought after during the Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, as well as trade beads, exchanged around the world for an even longer period. When the former Republic of Venice fell under Austrian control in 1797 and remained in that situation for most of the next 70 years, the populace endured economic hardship. At the time, art pilgrims on the Grand Tour hardly stopped at Venice. They considered it an impoverished, charmless spot, far inferior to Rome and Florence. Venice had to reclaim its position as a place of prosperity, vitality and artistic relevance.

A series of events and infusions contributed to Venice’s rejuvenation. Early in the process, English art critic John Ruskin’s book The Stones of Venice (1851-53) helped reawaken interest among architecture devotees. Circa 1859, Antonio Salviati set up a glass furnace to manufacture mosaic tiles for the restoration of St Mark’s Basilica with the revival of Murano glass occurring not long afterward. In 1872, lace production started afresh on Burano. These craft industries provided employment and reinforced unity, all the while raising the city’s arts profile.

In 1866, Venetians voted to join the recently formed nation of Italy. Three decades later, Venice mounted the first of the international art expositions now known collectively as the Biennali. During this period, foreign investment helped jumpstart the economy as well-heeled art lovers came to the Watery City in search of something different.

“A Venetian Woman” by John Singer Sargent, 1882. Oil on canvas, 93¾ by 52-3/8 inches. Cincinnati Art Museum, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1972.

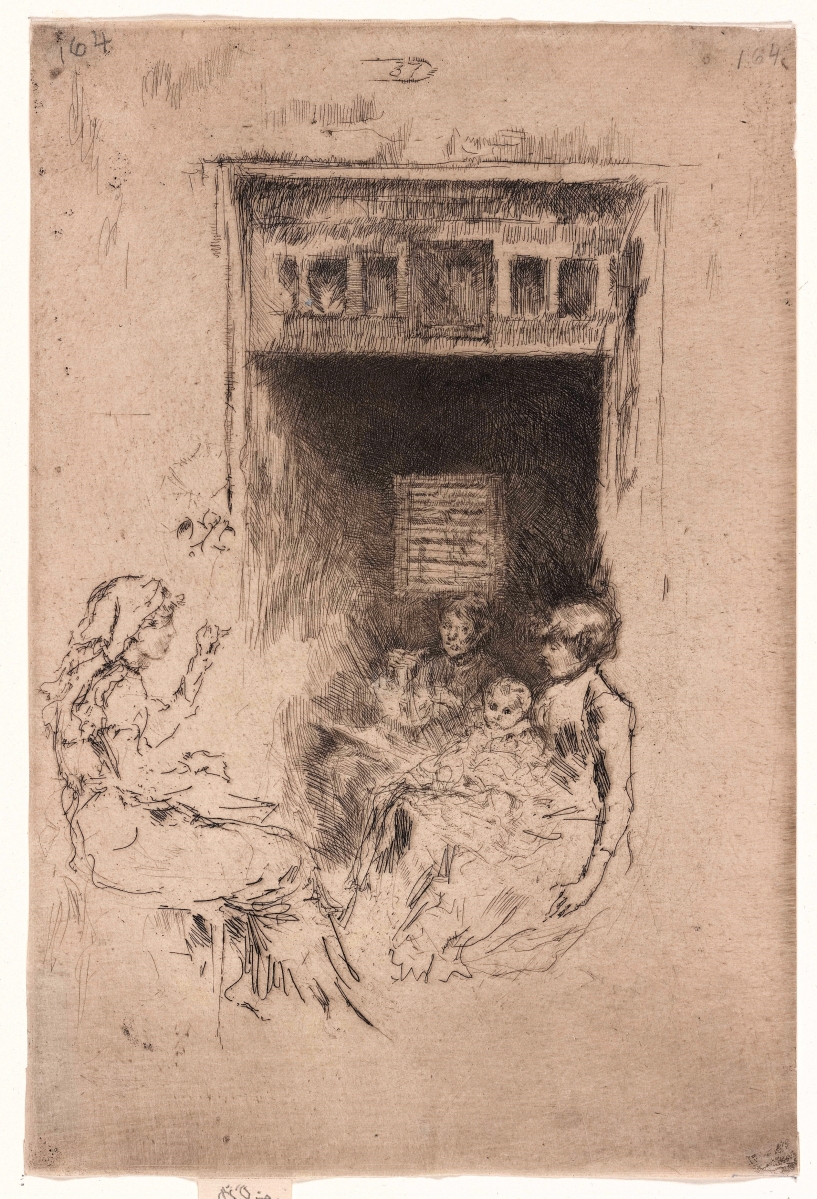

Indeed, artists arriving from the United States and elsewhere found themselves enthralled. Whistler immortalized his 1879-80 stay via atmospheric, groundbreaking etchings and pastels. Sargent created fresh scenes of everyday life and resplendent architecture during an 1882 sketching and painting trip, one of many he took to this locale. They, along with Maurice Prendergast, Frank Duveneck, Robert Blum and others, helped fuel Venice’s identity as an evocative, visually stimulating destination possessing an Orientalist flavor. Not only were they drawn to the art of Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese, but they were intrigued by working-class Venetians whom they considered picturesque, the character of the glass and lace industries, and the beauty of objects produced in these workshops.

Maurice Prendergast, perhaps the American artist best known for Venetian scenes, makes only a cameo appearance in this exhibition, yet manages to grab attention with his “Fiesta Grand Canal, Venice,” a nearly abstract mosaic of glass and ceramic tiles. SAAM’s senior curator of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century paintings, Eleanor Harvey, who has assumed management of the exhibition since Mann’s departure, remarked that when looking at Prendergast’s mosaic next to his “Ponte della Paglia” painting, “it hit me that he is riffing off of mosaics in his almost pointillist technique and it just makes me smile.”

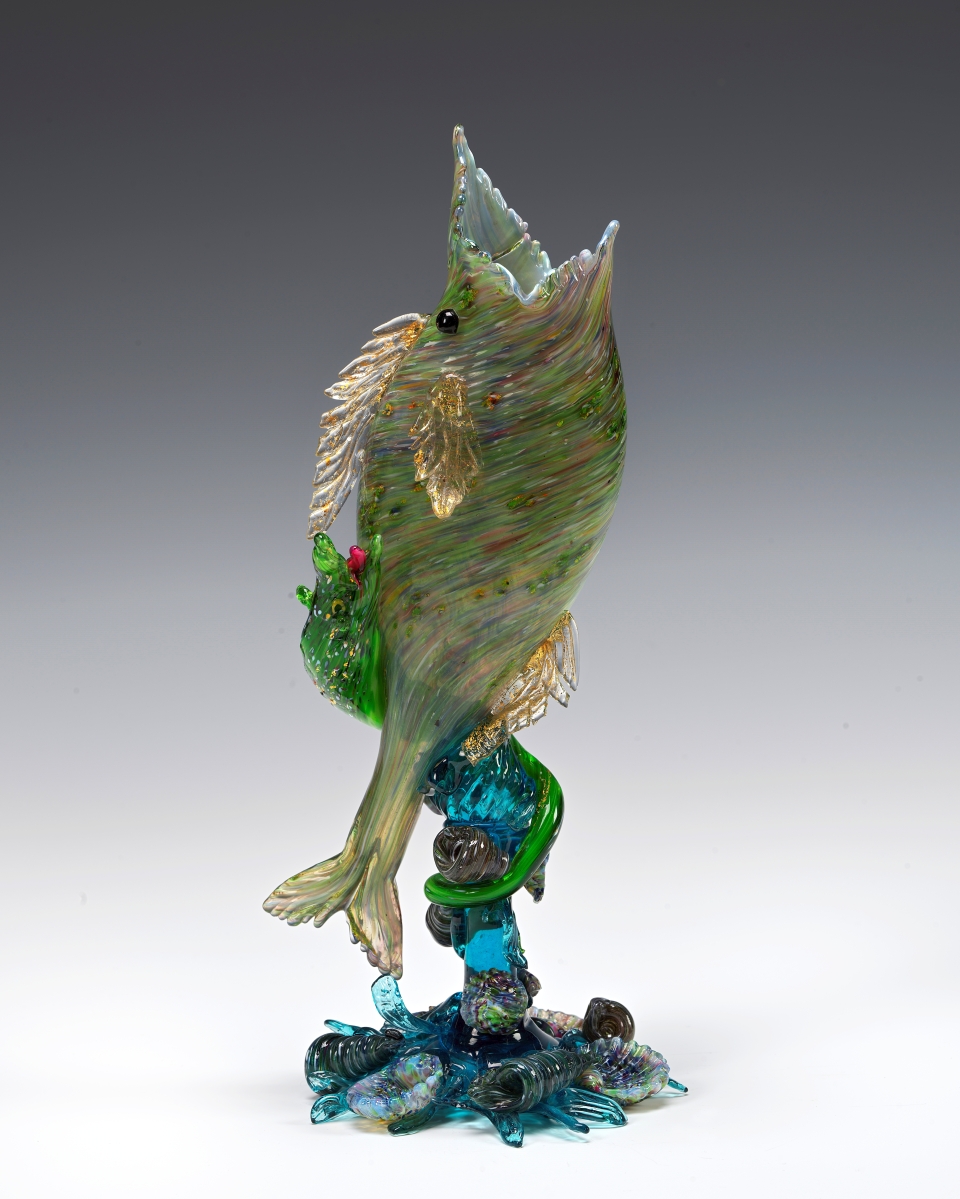

Venetian vases and drinking glasses are other showstoppers. What to think of a goblet with so much embellishment that a person can barely grip it, much less take a sip? Bold Venetian glassworkers fabricated sculptural sensations whose main purpose was to dazzle. (The idea of rebuilding craft traditions for the greater good may have possessed an Arts and Crafts vibe, but the resulting objects did not often embody a functionally derived aesthetic.

Although lace is not called out in the exhibition title, it is an essential component. As detailed in the catalog, the lacemaking technique developed on Burano during the Seventeenth Century was almost lost, until resurrected through a laborious process of transferring knowledge much like the revitalization of a nearly extinct language. Its renewal was celebrated in publications like Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. The tutelage of lace collectors in the United States was part of the formula. The absorbing tale is well told by Diana Jocelyn Greenwold in her catalog essay, “Interweaving Worlds, Antique and Revival Lace in Italy and in the United States, 1872-1927.”

Lace panel with Lion of St Mark made at the Scuola dei Merletti di Burano, Twentieth Century. Cotton needle lace, 4-9/16 by 6-5/8 inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Bequest of Gertrude M. Oppenheimer, 1981-28-460. The winged lion is the symbol of Venice’s patron saint and, by extension, the city itself.

Mann, Greenwold and their compatriots have done a great service by reintroducing these types of glassware and lace to contemporary audiences. Over a century ago, acquiring tour-de-force glass and lacework, as well as connoisseur-level knowledge of each material, was fashionable. The appreciation of these items plummeted with Americans’ sweeping rejection of Victorian design.

The relationship among American patron-collectors, Venetian art glass firms and their wares, and American cultural institutions is a strong subtheme. John Gellatly, Jane Lathrop Stanford and James Jackson Jarves bestowed Venetian glass upon the Smithsonian, Stanford University and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, respectively. Jane Stanford also commissioned Erede Dr A. Salviati & Co. to create mosaic decorations for the museum and the chapel at Stanford University. As a consequence, the firm donated three sizable collections of Venetian art glass to the new museum.

The accent here is on Venetian and American crosscurrents. As Mann spelled out, “At the Smithsonian American Art Museum we are interested in rethinking and expanding and challenging what we know about the history of American art by thinking about global conversations and how the visual identity of this country is the product, in many ways, of travel, of exchanges of ideas. This show is about those conversations and interactions and influences that go in both directions.”

Conical goblet with entwined serpents stem attributed to Giuseppe Barovier or Benvenuto Barovier, circa 1880s. Blown and applied hot-worked glass, 12-3/8 by 6-3/8 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.8.469.7. Observed SAAM’s senior curator Eleanor Harvey, “When people lay eyes on the incredibly sculpted goblets with intertwined dragons, leaping fish and filagree work, their jaws just drop. I think the glass really is the star of the exhibition.”

Harvey explained how curator Mann strategically positioned the major figures of Sargent and Whistler to get people’s attention, and then introduced the lesser-known makers he had targeted. “It’s a very accessible project because it is designed to coax you in and seduce you with light, color and delicacy, and then teach you something in the process.”

This effort to rediscover, and integrate, unjustly neglected art objects is laudable.

The lush yet sensitive design of the more than 300-page volume echoes the sumptuousness of the art enshrined in it. Scholarly essays cover the marketing of artistic Venice, the process of regenerating Venetian crafts, and American participation in the story. Glass and lace terminology is clarified through glossaries containing such exquisite words as fragole, fenicio and reticella. Engaging biographies of key artists, critics and collectors appear as an appendix.

As a companion offering at the Carter, Justin Ginsberg undertakes his “Shaking the Shadow” installation. Visitors can watch the artist draw glass threads, some of which will be 30 feet long, at a glass kiln on the museum’s grounds. He will combine these elements into a “waterfall” sculpture located in the main gallery.

“Water Carriers, Venice” by Frank Duveneck, 1884. Oil on canvas, 48-3/8 by 72-1/8 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Reverend F. Ward Denys, 1943.11.1. Duveneck, a native son of Kentucky, spent years working in Venice and Florence. Scholars view his dignified portrayal of laborers on the Riva degli Schiavoni as indicative of the artist’s confidence in the future of Italy.

“Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass” is not the only current exhibition celebrating Venice. “Unmasking Venice: American Artists and the City of Water” is on view at the Fenimore Art Museum (5798 NY Route 80, Cooperstown, N.Y.) through September 5. It contains works by contemporary and historical artists and is accompanied by a catalog.

“Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano” will be on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, at 3501 Camp Bowie Boulevard, through September 11; it will be mounted at Mystic Seaport Museum, (75 Greenmanville Avenue, Mystic, Conn.) from October 15 until February 27. For additional information, www.cartermuseum.org or 817-738-1933.

Editor’s Notes:

Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano. Edited by Crawford Alexander Mann III. With contributions by Sheldon Barr, Melody Barnett Deusner, Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, Stephanie Mayer Heydt, Crawford Alexander Mann III and Brittany Emens Strupp. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 2021, pp. 336, $65 hardcover.