Dala horses by Grannas A. Olssons Hemslöjd and Nils Olsson Hemslöjd, these examples produced circa 1970s. Collection of Todd Engdahl and Caroline Schomp, photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA, by Paul Salveson.

By Laura Beach

LOS ANGELES – Royal Copenhagen, Georg Jensen, Orrefors, Kosta Boda, Marimekko, LEGO, Dansk, Design Research, Creative Playthings, Knoll Associates, Jack Lenor Larsen, Volvo, and so many more. Nordic design and designers – and those influenced or trained by the same – so dominated the American consumer landscape over the past century that we scarcely recognize the enormity of their contribution.

The scale of the exchange between Nordic countries – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – and the United States is documented by curators Bobbye Tigerman and Monica Obniski in their magisterial book Scandinavian Design and the United States, 1890-1980 and an accompanying exhibition of the same name, the latter celebrating its American debut at the Los Angeles County Museum (LACMA) on October 9. Jointly organized by LACMA and the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM) in collaboration with their European partners, the show opened in Stockholm in 2021 before traveling to Oslo. It wraps up its tour in Milwaukee in 2023.

The “and” in the show’s title is definitive. Tigerman, LACMA’s Marilyn B. and Calvin B. Gross curator of decorative arts and design, and Obniski, who left MAM in 2020 to become curator of decorative arts and design at Atlanta’s High Museum, reject the traditional view that the Scandinavian style moved in a linear fashion from Europe to the United States, instead demonstrating the ways in which the exchange was reciprocal and influences were ambient. They question what defined Scandinavian Modern design, misnamed in the sense that Iceland and Finland are technically not part of Scandinavia, and argue that, led by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen (1873-1950) and his circle of Nordic instructors, Cranbrook Academy of Art shaped what may be the greatest generation of American designers.

“The last major, multidisciplinary, multi-country Scandinavian design show was at Cooper-Hewitt Museum in 1982. Interestingly, it’s around then that Scandinavian design declined in popularity, to be rediscovered in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The ideas associated with the earlier era persist. We wanted to show how these ideas – often mythical, stereotypical ideas about Scandinavian design being organic and comfortable, a sort of gentle Modernism – were received in the United States and what it meant that they were so popular at the time,” Tigerman explains.

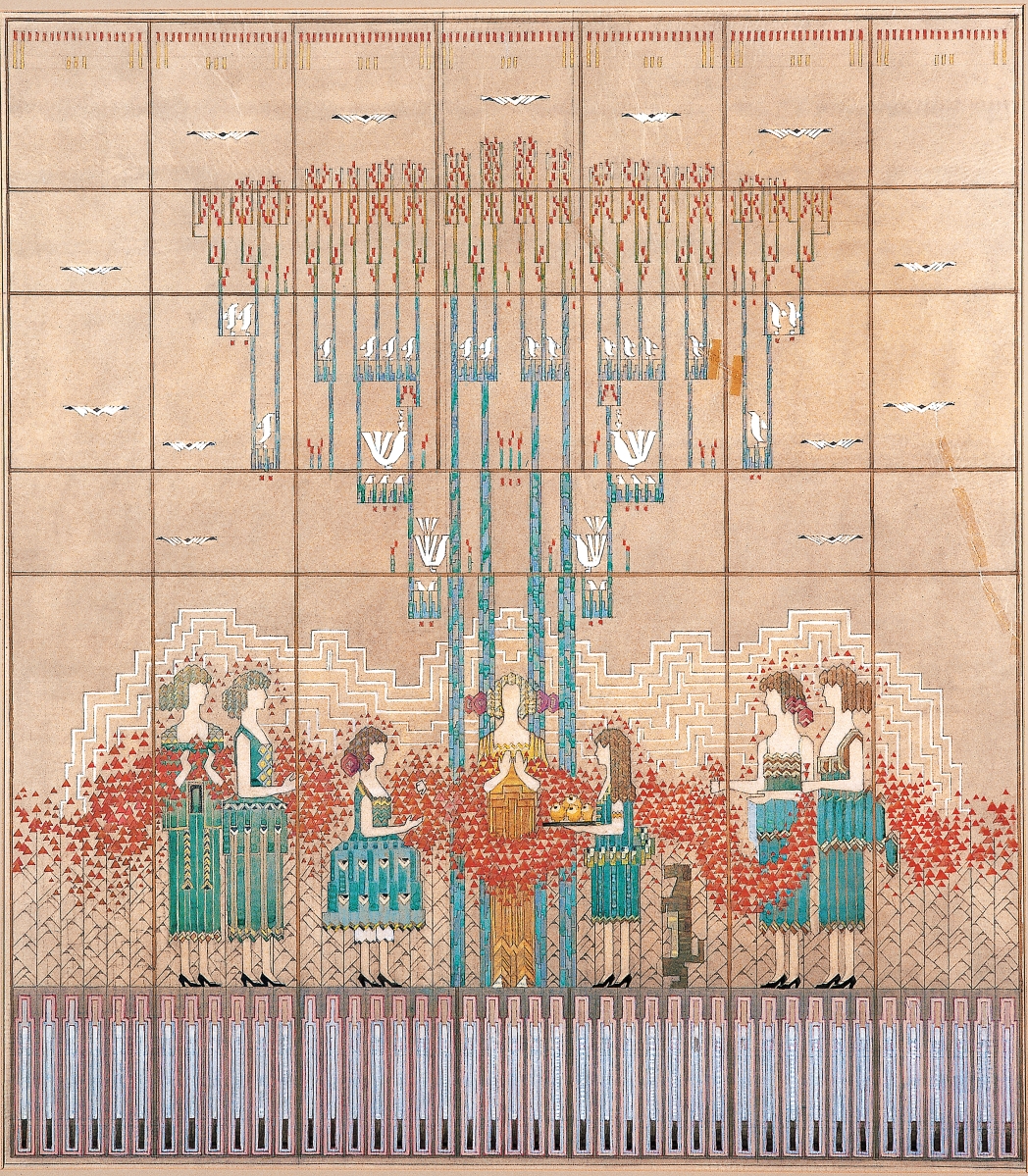

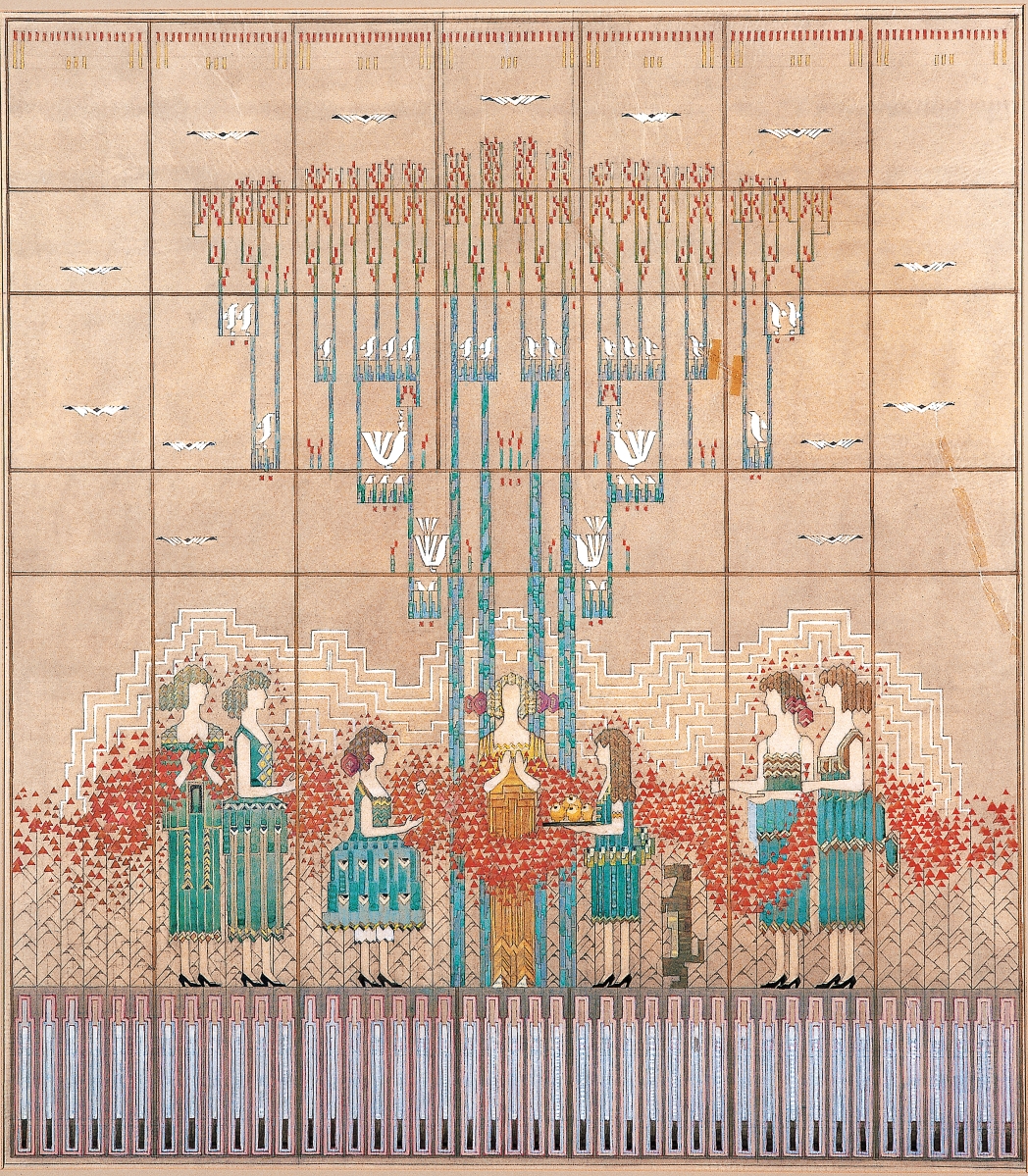

Study for “Festival of the May Queen” hanging by Eliel Saarinen and Loja Saarinen, Kingswood School, 1932. Cranbrook Art Museum, ©Eliel Saarinen® and ©Loja Saarinen, photo ©Cranbrook Art Museum.

Tigerman and Obniski – friends since 2005, when they served as intern and research assistant, respectively, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – in 2014 began discussing an exhibition devoted to the American embrace of Scandinavian design. As planning got underway, each brought a regional perspective to the project. At MAM, Obniski considered the contributions of Scandinavian immigrants to the upper Midwest. Tigerman’s interest was in part piqued by her work on the LACMA exhibition “California Design, 1930-1965: ‘Living in a Modern Way,'” which showcased, among others, the Swedish architect and designer Greta Magnusson Grossman (1906-1999), who settled in Los Angeles.

Ranging from folk art to industrial design and featuring more than 175 examples of work in all media, LACMA’s presentation draws from collections at home and abroad. The California angle is reflected in LACMA’s selection of Los Angeles-based architect Barbara Bestor as exhibit designer. Of Bestor, Tigerman says, “Her signatures are bright colors and energetic spaces. Bestor grew up in Cambridge, Mass., exposed to Design Research, a prominent retailer of Scandinavian design. She drew her color palette from the show’s objects, but her installation scheme echoes the design work of Deborah Sussman (1931-2014), who created the visual language and ‘kit of parts’ strategy for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.”

Installed on level two of LACMA’s Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) and divided into six thematic sections, the show opens with an exploration of “Migration and Heritage.” Nordic people moved to the United States in great numbers beginning in the mid-Nineteenth Century. They were often viewed as model immigrants – wholesome, hardworking and rustic – lingering stereotypes that attach to Scandinavian decorative arts, as well.

Catalog contributor Graham C. Boettcher writes that the 1887 dedication of a monument in Boston to the Viking explorer Leif Eriksson, touted by some at the time as the true European discoverer of North America, set off “a brief but intense Viking moment in American fine and decorative arts.” International expositions helped popularize the Scandinavian dragestil, or “dragon style,” and the Viking Revival, as expressed in the United States by Gorham’s “Viking Boat” silver centerpiece of about 1905. By the 1930s, America was awash in rosemaling, a decorative painting technique promoted by Per Lysne, a Norwegian who settled in Wisconsin, and colorfully painted Swedish Dala horses, an American fad for which was launched by the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

“Viking Boat” centerpiece by Gorham Manufacturing Company, Durgin Division, model D 900, designed circa 1905. Collection of the Art Fund, Inc. at the Birmingham Museum of Art; purchase with funds provided by Guy R. Kreusch, photo ©Birmingham Museum of Art, by Sean Pathasema.

The crucial section “Teachers and Students” documents the institutions and instructors responsible for disseminating Scandinavian style in the United States. A locus of instruction was the Cranbrook Academy of Art (other hotspots were the Rhode Island School of Design and Penland School of Crafts). Eliel Saarinen designed Cranbrook’s campus and curriculum and hired as instructors the ceramist Maija Grotell (1899-1973) and weaver Marianne Strengell (1909-1998), both Finns, and the Swedish sculptor Carl Milles (1875-1955), among others. Cranbrook’s progeny included Charles (1907-1978) and Ray Eames (1912-1988), Florence Knoll (1917-2019), Ed Rossbach (1914-2002) and Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011).

The curators delight in the web of personal relationships underpinning the American design field in the mid-Twentieth Century. In the LACMA display, one of Tigerman’s favorite juxtapositions is a tapestry of circa 1954 by the Finnish weaver Martta Taipale (1893-1966) and a 1959-60 hanging by the American Lenore Tawney (1907-2007), whose career was transformed by a workshop she took with Taipale at Penland in 1954. Fiber art by Strengell, Dorothy Liebes (1897-1972) and Alice Kagawa Parrott (1929-2009) complete the display. “It’s an amazing circle of objects,” says Tigerman, confessing her fascination with “networks of people who connect and share ideas.”

“Travel Abroad” picks up where “Teachers and Students” leaves off, painting a picture of Americans who pursued training or experience in the Nordic world. Tigerman was delighted to become acquainted with Howard Smith (1928-2021), an African American artist who worked in Finland. “He was a remarkable person whose story really spoke to me. He spent time in Los Angeles, but Finland provided freedom and the opportunity that eluded him in the United States,” says the curator.

As illustrated in the section “Selling the Scandinavian Dream,” canny marketing contributed to America’s wholesale embrace of Nordic design. Even the Kennedy White House was in on the action. Invented by the Danish woodcarver Thomas Dam (1915-1989), the best-selling troll doll made it to the Oval Office. Soon to be First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated wearing a dress by the Finnish firm Marimekko, known for its bold, floral prints and simple silhouettes.

Vase by Guðmundur Einarsson and Lydia Pálsdóttir, Listvinahús (Iceland), 1939, stoneware, 14-15/16 by 7½ by 7½ inches. Private collection, photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA, by Ragnar Th. Sigurðsson / Artic-Images.

There was no greater booster of Scandinavian Modern design than editor Elizabeth Gordon (1906-2000), who pitched the style relentlessly in House Beautiful magazine. Gordon was also instrumental in launching the enormously influential exhibition “Design in Scandinavia,” which opened at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 1954 and traveled to 24 venues in the United States and Canada before closing in 1957.

Reflecting on the reach of Scandinavian design into nearly every facet of American life, the curators conclude with sections on “Design for Diplomacy” and “Design for Social Change.” The most compelling example of the former is the United Nation’s headquarters in Manhattan, where, as Obniski details, architects and designers from Denmark, Norway and Sweden styled the three most important chambers. Denmark’s Finn Juhl (1912-1989) provided furniture for the U.N.’s Trusteeship Council Chamber, however, it was another Dane, Hans Wegner (1914-2007), whose chairs appeared as props in the televised Kennedy-Nixon debate of September 1960.

In “Design for Social Change,” the curators explore the ways in which the 1950s focus on “good design” shifted in the 1960s and 1970s to an international discourse on ergonomic, environmental and social concerns. Both LEGO blocks and the BabyBjörn carrier – the latter’s American counterpart was the Snugli – were characteristically Nordic, promoting wholesome domesticity through simple, well-made products.

Globalism is a fitting coda for the show. One need only think of IKEA – founded in Sweden, headquartered in the Netherlands, with 2021 sales of $42 billion – to appreciate the inherent tension between regional design and mass sourcing, manufacturing and distribution. But while global commerce ultimately blurred the contours of the Scandinavian design movement, advances in communication have enhanced curatorial collaboration. Tigerman and Obniski traveled to Norway and Sweden to visit the first two installations of their show. As Obniski relates, the colorful, exuberant presentation at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm – Sweden’s art and design museum – amplified areas such as industrial design, while the Nasjonalmuseet Oslo showing was “minimal – white walls, plywood dividers, light-colored curtains – allowing the brightly colored objects to sing.” Tigerman notes, “Our counterparts were excited to borrow American pieces. Scandinavian designers are household names in many Nordic countries, but American design – even common objects by Charles and Ray Eames and Harry Bertoia, for instance – are less familiar.”

Chair by Jens Risom for Knoll Associates, Inc., model 650, designed 1941, this example circa 1947. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Mr Oliver M. Furth and Mr Sean Yashar, photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA.

Cultural conversations are never really over. “It would be difficult to imagine the current vibrant energy in the Scandinavian craft scene without the influence of Americans from the 1960s and later, and the continuing exchange of ideas since,” catalog contributor Glenn Adamson writes, concluding, “at a time when postwar studio craft is being reappraised, the transformative encounter between America and Scandinavia must be seen as one of its greatest success stories.”

Obniski says, “I consider this project a beginning – in a way, it opens doors for future research and continued development. One area I regret not having enough time to pursue is further lines of inquiry within industrial design education and practice. I am convinced that there are many more stories to uncover.” Tigerman reflects, “Many of the designers we discuss are still waiting for monographic treatments or group shows to highlight their contributions.”

Co-published in 2020 by LACMA and DelMonico Books-Prestel, Scandinavian Design and the United States, 1890-1980 includes essays by 16 contributors in addition to those by its principle authors, Tigerman and Obniski.

Following its close in Los Angeles on February 5, 2023, “Scandinavian Design and the United States, 1890-1980” travels to the Milwaukee Art Museum, where it will be on view from March 24 through July 23, 2023.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is at 5905 Wilshire Boulevard. For more information, go to www.lacma.org.