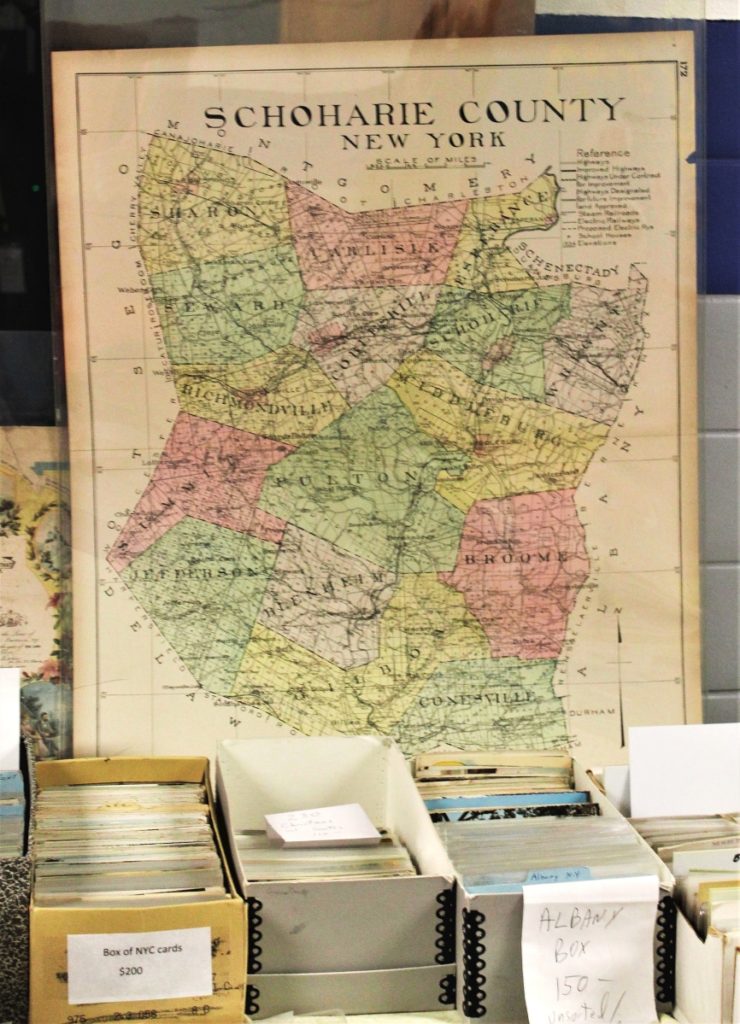

John Duda appealed to regional pride with this leaf of Schoharie County from the New Century Atlas of Counties of New York State, 1912, offered for $100.

Review & Onsite Photos by Z.G. Burnett

SCHOHARIE, N.Y. – Amid drizzle and snow flurries, there was no slowdown to the setup within the Schoharie Central School for the Schoharie Colonial Heritage Association’s Spring Antiques Show on March 25 and 26. There was a shuffle of excitement within every occupiable space in the school on Saturday morning, which hosted more than 90 dealers as well as a full staff of volunteers running the kitchen and manning other charity-based project tables among the antiques. This was the first time in three years that the Schoharie Antiques Show was able to set up in the school, and the excitement was palpable. “The show was a great success,” said Jim and Mara Kerr, who were helping with the show’s advertising for the first time this year. “Most dealers seemed happy with sales.” The Kerrs reported “a smaller but still steady crowd” on Sunday, which would have been a healthy turnout considering the near crush of attendees on Saturday. More than a few masks could be spotted, but crowds appeared to be back at a pre-pandemic level.

Dealers’ booths were spread throughout the school with no corner or hallway space spared, and there was merchandise available for truly all types of collectors and budgets. Many dealers were veterans of the Schoharie show, some participating for up to two decades, and others were relative newcomers having only been in the business half a decade or so. Nancy and Jim Douglas of Clifton Park, N.Y., have shown at Schoharie 15 times, and their booth offered a broad array of Americana, including pewter, pottery, toleware and more. Sitting atop an early Nineteenth Century tiger maple two-drawer chest was an unusual dome-top tea chest from the same era, decorated with scrimshawed bone panels and brass nails, priced at $750.

This Nineteenth Century apothecary chest from Richard Fuller, Royalton, Vt., sold early on Saturday, and he was chatting with its new owner when we asked about the piece.

Matt Reuter, Delmar, N.Y., was setting up for the second time at Schoharie, although one would not know it by his stock. The central piece of Reuter’s booth was also tiger maple and from the late Eighteenth to early Nineteenth Century, but most likely of a different origin; a carved working bowl like those used by the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy for $1,250. After buying the bowl in Rhinebeck, N.Y., Reuter took it to the Iroquois Museum in Howes Cave, N.Y., where he consulted with Six Nations’ tribe members from Ontario, Canada. Opinions were “split” as to whether or not the bowl was of colonial or Indigenous origin, but those present confirmed that the bowl was much like others the tribal representatives had seen and used that were passed down in their communities.

Next to this booth was that of Scott Penpraze, Eastfield Village, N.Y., who has been showing at Schoharie for the past 20 years. Penpraze brought a refined selection of early American and English bottles, a category that has been overlooked for the past few decades in the larger antiques world but is due for a comeback. One of the best examples was a black glass mallet wine bottle from the late Eighteenth Century, marked with the seal of “Mrs Murray 1772.” These seals indicate the owners of family-run wineries, and Mrs Murray is not listed in David Burton’s Antique Sealed Bottles 1640-1990 (2015) and does not appear in a cursory Internet search. Because Burton’s book focuses mainly on British wine bottles, this could mean that Mrs Murray was an American distributor, is a yet undiscovered proprietress of the industry, or both. Either way, it was a fantastic potential research project for $1,150.

Another object of hazy origin was an early Twentieth Century papier-mâché American eagle perched prominently in the booth of Janet Sherwood of Cambridge, N.Y., for $295. Standing about 2 feet high and 3 feet wide, the eagle looked barely used with minimal wear around its edges and no fading of its golden paint. Most likely created for some kind of celebration, Sherwood was not exactly certain of its age or origin.

Bob Mock of Mockingbird Period and Decorative Antiques, Niskayuna, N.Y., had already sold five case pieces, a few large paintings and other antiques by 10:40 am on Saturday.

Nearby in the cafeteria, Joe Fava of Joe’s Follies, Ballston Spa, N.Y., displayed a collection of three Bunraku-type masks made around 1790 in the Edo period. Bunraku is a traditional form of puppet theater, but these were larger than the typical puppet size. The fragile masks were contained in their original wooden cases, which would have been collector’s pieces on their own. Altogether, Fava was asking $385 for the set.

Christine Buchanan-Smith, New York, was also dealing in miniatures but of the dollhouse variety. Her hallway table was piled high with artfully arranged, tiny goods, aided by a few potted tulips and hyacinths that drew customers like bumblebees. Buchanan-Smith’s moderate prices kept them there, starting at $1; customers added to their piles while waiting in line and often had quite a few items to ring up when it was time to settle.

Off the path from the populated hallways was the country kitchen-esque setup of Hirsch Antiques, Pleasant Valley, Conn., represented by Jamie B. Heuschkel. Right near the entrance of this alcove was a crewelwork trade sign that read “Welcome” within a floral arrangement, supported by an adjustable wooden stand, priced at $195. Heuschkel explained that the sign itself was early Twentieth Century, most likely made for promotion, and that the stand was even earlier, likely from the late Nineteenth Century.

Maureen Poulin of A Feathered Nest Antiques, Esperance, N.Y., led the Easter Parade with a wide selection of moderately priced decorations.

Another example of early stylistic collaboration was found in John and Dannette Darrow’s booth. Peeking out from underneath a table was a pair of andirons, which John described as “early Nineteenth Century copies of Eighteenth Century [originals].” The deep, iron dogs and stands supported delicately wrought iron finials in a thistle-like pattern. This indicated that the andirons may have been Scottish, or made by someone of that origin. They had seen use and sported a suitable patina but were still fully functional and offered for $295.

Portraiture was also well represented at Schoharie, especially in the school’s larger gymnasium. Here Peter Bazar of Saratoga Fine Art, Saratoga Springs, N.Y., presented a late Nineteenth Century portrait after “Mrs Mayer and Daughter” by Ammi Phillips (American, 1788-1865), 1835-40. This painting was smaller than the original at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and far more flattering to the sitters. Bazar believed that it was painted by an unknown follower of Phillips, which was remarkable for its excellent condition and asking price at $3,750. Another “pleasing portrait” of a young woman, 1830-1850, was offered by Bazar’s gymnasium neighbor, Mark Wheaton, Mariaville Lake, N.Y., for $695. This lady’s image had been cleaned and little restoration was found for Wheaton to report.

The 47th Fall Antiques in Schoharie show is scheduled for September 23-24 at the Historic Valley Railroad Complex, 143 Depot Lane. For additional information, www.schoharieheritage.org or contact show manager Ruth Anne Wilkinson, 518-231-7241.