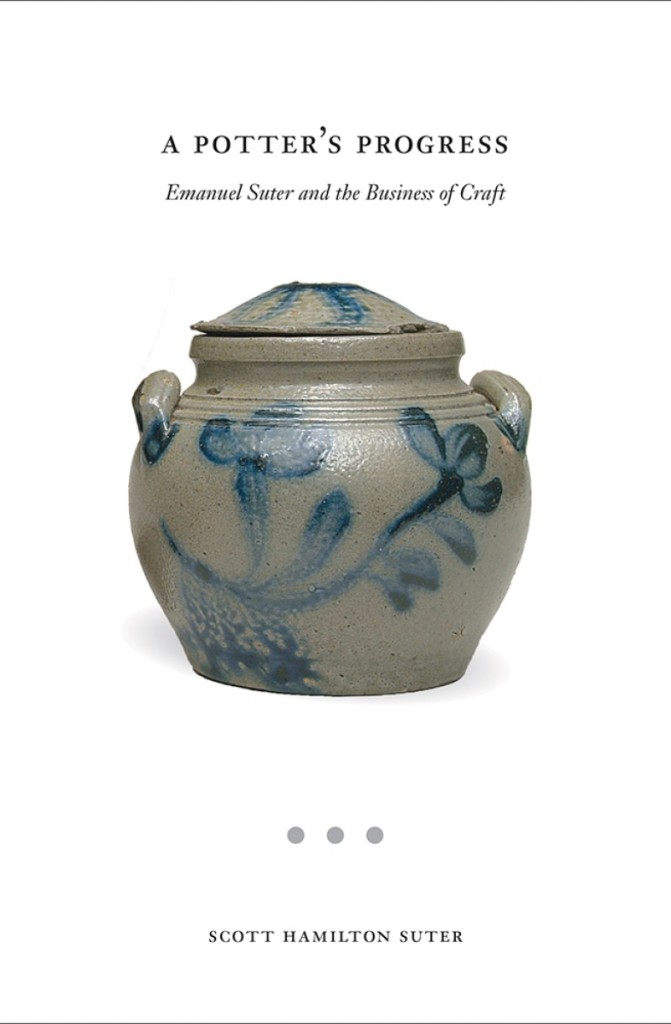

Nineteenth Century Shenandoah Valley potter Emanuel Suter is an artisan worth knowing. The top end of his market is governed by an $88,250 result for a stoneware honey or sugar pot decorated with a cobalt triple-bloom flower. But to know a man, and not just his market, you have to ask him questions. We did the next best thing by sitting down with Scott H. Suter, the potter’s great-great-grandson, a professor of English and American studies and director of the Margaret Grattan Weaver Institute for Regional Culture at Bridgewater College in Virginia. Suter has just released his new book, A Potter’s Progress: Emanuel Suter and the Business of Craft. The author pored over the archives to bring forth a story about a man who straddled the line between tradition and progress, offering more than a gander at the valley’s regional stoneware production at a time of immense change.

When did you first learn about your great-great grandfather?

I knew about him when I was quite young, when most kids are not interested in that sort of stuff. There’s a lot of interest within the Suter family in genealogy, so I knew he was a potter. The family has always told stories about him. He had a bunch of children, so the family spreads out, but we have a family reunion every two years. There’s real attention paid within the family of Emanuel Suter and his father, Daniel, who immigrated to the United States. It wasn’t until I was just about finished with my bachelor’s degree that I was in an antiques store and saw a piece that had Suter written on the tag. I thought “Hey, that’s kind of cool, I ought to look into this.” Then I went to UNC for my master’s degree, and while I was there I started to realize I had an interest in folklife, and I took a course called Traditional Craftsmanship with Terry Zug, a North Carolina pottery scholar. I thought “This is cool, he’s talking about potters and my great-great-grandfather was a potter.” So I went and talked with him and he was excited and encouraged me to pursue it, so I wrote a paper about Emanuel Suter for that class and that was probably the first time I really did some research on the topic.

Does the Suter family have a collection of Suter pottery?

Oh yes, many of the family members have collections.

I have a few pieces, too.

Tell me about Emanuel Suter.

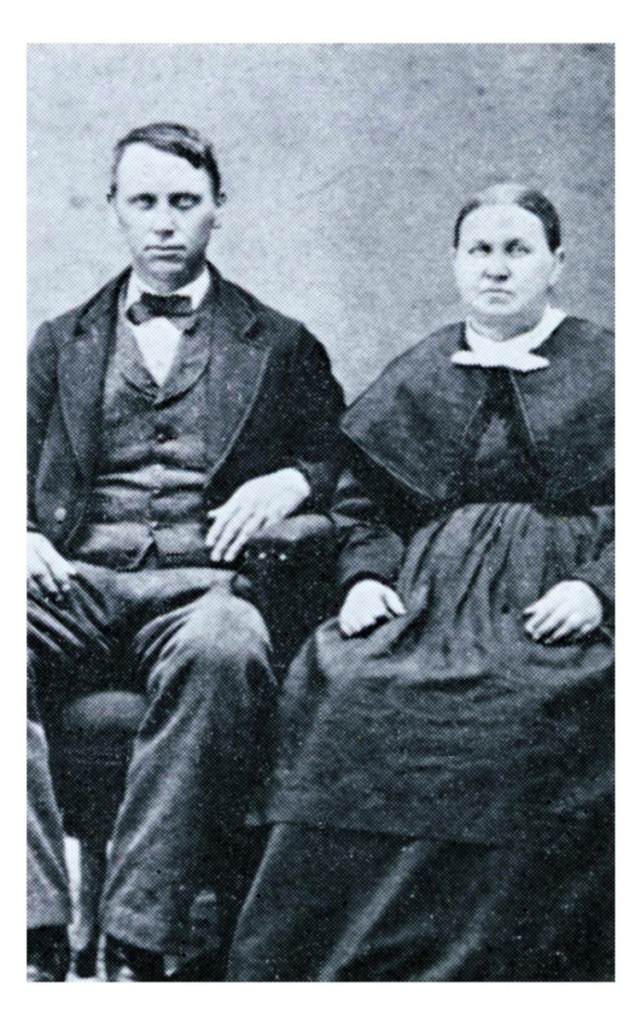

By all accounts, he was well respected in the community. He and his wife joined the Mennonite Church in 1855, the year they were married. They were devout people their entire lives. At the end of each diary entry, Emanuel Suter would frequently write little devotional phrases, such as “Hold fast to the Bible as the sure anchor of liberties. Write its precepts on your heart and practice them in your lives.” He was a respected member of the church and served on important committees. He had progressive ideas, but people didn’t hold that against him. He was also interested in public education, even though from what I can tell he didn’t have a lot of education himself. He read all the time and worked to get public schools built in the county.

Scott H. Suter’s new book, A Potter’s Progress:

Emanuel Suter and the Business of Craft,

is published by The University of Tennessee Press, 2020, 149 pages.

When did he learn pottery?

He grew up living and working on a farm. The oral history is that at the age of 18, Suter went to work with the potter John D. Heatwole, who was his cousin and elder by three or four years. Heatwole had learned from his father-in-law Andrew Coffman. So Suter would have been farming and then learned his trade of potting, but certainly all his life he was both farming and running the pottery. Most of the traditional potters, at least in Rockingham County, worked seasonally. When they weren’t farming, they were making pots. One of my arguments is that Suter changed that. He said ‘I can make pots year round,’ and it became more of a business than a side job.

Tell me about the farm.

Apart from leaving the Shenandoah Valley between October, 1864, and June, 1865, he and his family lived on a farm in a community called New Erection, west of Harrisonburg in Rockingham County. His wife’s name was Elizabeth Swope, and it was her father’s farm. Shortly after Emanuel and Elizabeth married, her father moved off the farm. It’s clear that Suter was operating a pottery shop there shortly after he moved to the place.

How did the Civil War affect his life?

In the Shenandoah Valley, we have large communities of Mennonites and Churches of the Brethren. These are pacifist groups, and largely were not slave owners in the Nineteenth Century. When the Civil War came, many of them were coerced to vote for Secession. In those days, people knew how you voted, it was public. So Suter voted for Secession, but I think only because he was physically threatened with death. He refused to join the Confederate army, and one of the things you could do was furnish a substitute. So he first got someone to go in his place who was not a Mennonite and then saved up money – you could pay $500 to be exempt – so he saved up $500 so his substitute didn’t have to fight anymore. Of course $500 was quite a sum at the time.

In 1864 he went to Pennsylvania to escape the Valley during the war. This is when he started to keep a diary, and he kept it for the rest of his life. When he was in Pennsylvania, he worked briefly at Cowden and Wilcox in Harrisburg, and that changed his life.

He was making pottery when he came back from Pennsylvania; he talks about turning ware at this time, so he had a shop on his farm and there are a few receipts and dated pieces that are around 1860 and 1865, which indicate that there was an existing shop on the farm. But it was when he came back from his brief work at Cowden and Wilcox that he started drawing up a plan for a new shop and new kiln. When you look at the one photo of the New Erection pottery and compare it to the Cowden and Wilcox pottery, you see this distinctively shaped kiln. It’s not a round beehive kiln, it has squared sides and kind of a trapezoid form. It’s a clear indication that Suter said “I want mine to be like that one.” It was much larger than any of the other potters’ kilns here in this county.

The New Erection pottery, 1885. This is a hand-tinted version of a black and white original image. Courtesy of the Virginia Mennonite Conference Center.

What kind of documents did you source from?

The primary source is the Emanuel Suter papers in the Virginia Mennonite Conference Archives at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Va. His diaries and other business and personal papers are preserved there. There was an attic in the house and, from what I understand, the papers were stored there in boxes. One of his granddaughters inherited that house and lived there most of her life. I knew her towards the end of her life. She was the family historian and she guarded these materials and eventually gave them to the university to be preserved – it’s a great collection.

He operated three potteries over 46 years. Run through each of them individually.

The first was started when he moved to the farm in New Erection, and he operated it until he left in 1864. I don’t know much about it, there aren’t records. But I’ve surmised it was a sizable shop, because when he came back, after he cleaned up, he started to turn pots. And he did so for quite some time before firing a kiln. He would have had to have some place to store these pots while they were waiting, so I suspect he had a functional shop on the farm during the Civil War.

He came back in June 1865, and by August he started making plans for a new shop. By 1866 it was complete and the new kiln was operating. That’s the one in the photograph in the book. He operated this one for many years, 1866-90. He was making utilitarian pieces, as all potters were. Much of his stoneware was decorated, but he was never an effusive decorator. There’s some cobalt on pieces, but not a whole lot of decoration compared to other area potters. There are exceptions to that, of course. He made stoneware, but as time went on, in the 1870s and 1880s, he focused on earthenware. Some have argued that this was strange because at this time people started to realize that we shouldn’t be eating off lead-glazed pieces. But he was turning functional pieces – he started making drain tile, flowerpots and pans, stove flues, chimney thimbles. He really did aim for making it a business. My book shows he was a progressive-minded person, and I look at how that manifested in the potteries.

In 1890 in the Shenandoah Valley, communities were booming and there was a lot of economic expansion. There was one group of investors that bought a large piece of property north of Harrisonburg along the railroad tracks, and they were promoting various businesses. There was another pottery that went in there that was producing molded ware such as Rebekah at the Well teapots, and the business leaders talked to Suter and he decided to incorporate and move to Harrisonburg and make his pottery as modern as it could possibly be, calling it the Harrisonburg Steam Pottery. At this point he realized that the Shenandoah Valley tradition was behind the times. So he made trips to Ohio – Zanesville and Roseville – and visited potteries. Then he went to Trenton, N.J., and met with owners of clay mines. He was trying to become less regional and more East Coast-oriented. His inspiration was to just keep moving forward with his business. It didn’t work out so well, as the book points out. It was doing okay, but it was also not doing okay. He overextended the business, perhaps.

Did he just close up?

That was in 1897. He didn’t write too much in his diary – it’s not a heartfelt diary, its just more, “This is what I did today.” On this day he wrote, “I was in town on business at the pottery, sold it for $2,000, this relieves me of further trouble with that works.” That was it, a very cryptic comment. The pottery continued to operate for a couple of years afterwards under different management. He died in 1902, so he lived and farmed for five more years.

Did he have trouble turning out volume?

No. He started buying clay from New Jersey; it had to be shipped here. Then he had to ship his ware out to the new markets. He was firing this new kiln with coal, as opposed to wood. Like the clay, coal came from somewhere else. Harrisonburg was far enough away from the resources that it couldn’t compete economically. I’m not an economist, but I think that’s accurate. None of the industries that were touted during that 1890s boom period actually lasted in Harrisonburg.

Were there any singular points in his production that he learned something new and you can see it in the timeline of his work?

One thing that stands out to me was that he bought a steam engine and put it in his New Erection workshop. He says in his diary that he went to town for a line shaft for the pottery. It was like a big factory in there. He could turn the wheels or grind the clay using the engine.

Suter had a local blacksmith build a tile press according to his design. So instead of turning hollow pipes, he could now press them. And you can look at some pipe pieces and see clear extrusion marks where they were just rammed through the press.

When he incorporated and moved into town with his third pottery, he still had people turning ware, but he had at least one jigger wheel. There are examples from that pottery that are completely undecorated and were clearly produced on a jigger. Examples of that ware are pictured in the text. So you can definitely see a progress through time.

Where does he fit within the context of Shenandoah Potteries?

He was part of this familial tradition in Rockingham County. He learned from Heatwole, who learned from Coffman, who had numerous sons who were potters. Another potter, John Ford, married one of Heatwole’s daughters, so it was a family as well as a community tradition.

This is the story of how one traditional craftsman moves that tradition into industry. He worked here in the county and he tried to expand marketing areas. He was selling loads of ware over the mountain in Charlottesville, and was selling ware in Winchester, about an hour’s drive today north of Harrisonburg. Between those two lies Strasburg, which was the pottery center of the Shenandoah Valley at the time. He faced a lot of competition. There were a number of potters just in Rockingham County alone, but he tried to sell in Shenandoah County and Frederick County, the two counties north of him. There’s a letter from a cousin of his who lived near Strasburg, in which he writes, “I don’t know how well you’re going to do up here because of the Strasburg monopoly.” But he did sell some ware there, especially in Winchester. When he was in Harrisonburg, he was marketing his ware and selling carloads to people in New York City, Baltimore and Washington, DC. He was really trying to expand. But in the valley, he worked in that folk tradition. Potters in that tradition produced attractive and individualistic pieces. This is how he learned, but my argument is that he moved beyond that. The tradition really started to dry up, as is true of most pottery traditions, by the end of the Nineteenth Century.

What was it was like going through his notes – any revealing moments?

There were some. I took the idea of progress from his diary. He wrote “May we realize the importance of making progress in everything we have before us, be it secular or spiritual.” That was in 1893. I thought that was his primary idea, this was what motivated him in life, the idea of making progress. There’s a dichotomy between being a traditional person and this notion of progress. In 1897 he wrote, “Today I purchased a phone over a phone.” To me, that was so cool. He was postmodern before the term existed! There aren’t many places where he indicated profound moments for himself. He was very understated. Many people think of Mennonites as being conservative and doing things in the old ways, but here’s a guy doing everything he could – using technology, selling reapers to people who were still using flails – who bought a steam engine to thresh with. When I saw these things in his diaries and papers, I saw them as confirmations of his progressive attitude.

The main point that I would like people to take away is that he provides an example of how a craftsman could change his techniques and designs from the tradition in which he was based. And in a way, folk arts had to change. The uses of traditionally crafted items started to fade away at this time, and craftspeople weren’t just making things for fun, it was their jobs. If people didn’t see a need for these items, then the craftspeople had to find something else to do. I see Emanuel Suter as an individual on the cutting edge who was moving along, progressive in his thinking.

A Potter’s Progress: Emanuel Suter and the Business of Craft is available at https://utpress.org/title/a-potters-progress or on Amazon.

-Greg Smith