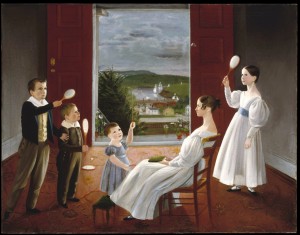

“The Children of Nathan Starr” by Ambrose Andrews (1801–1877), Middletown, Conn., 1835, oil on canvas, 283⁄8 by 36½ inches. Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, gift of Nina Howell Starr, in memory of Nathan Comfort Starr (1896–1981), 1987. Image ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Resource, New York.

NEW YORK CITY — “Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America,” an exhibition of works of art that capture posthumous likenesses, be on view at the American Folk Art Museum October 6–February 26. The exhibition explores the important and underrecognized genre that captured a memorial portrait of its subject after death.

“Mary and Francis Wilcox” by Joseph Whiting Stock (1815–1855), Springfield, Mass., 1845, oil on canvas, 481⁄16 by 40 inches. Collection National Gallery of Art, Washington, gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

At a time when images of loved ones were precious and few, capturing a shadow held a particular urgency for families. More than 120 works of art — gravestone photos and monuments, painted portraits, death casts and postmortem daguerreotypes — from the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries will be shown. Stacy C. Hollander, deputy director for curatorial affairs and chief curator of the American Folk Art Museum, is the curator of this exhibition.

“Memorial portraits are an important genre in American art history of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries. They form a visual record of family life, social mores and religious and secular attitudes toward death that help us understand life in the pre-modern era,” commented Dr Anne-Imelda Radice, executive director, American Folk Art Museum.

The exhibition will examine ways in which Americans have understood death and remembrance as the culture changed from the Colonial period through the Nineteenth century. Gravestones are witnesses to the transition from allegorical and emblematic imagery to living portraits of the deceased. This evolution reflected a shift in society itself, as the center of life moved from the locus of community to the individual family and its constituent members. They also established a lexicon of symbols that increasingly emphasized the redemptive quality of death and rebirth in a better world. Many of these symbols had deeper roots in mythological and biblical texts and in art historical precedents. A widespread conversance with this language enabled posthumous portraits to be easily “read” by those who beheld them. Such symbols were employed in portraits that might not otherwise be recognized as posthumous.

More than 40 paintings by artists including Charles Willson Peale, Oliver Tarbell Eddy and well-known self-taught artists, such as William Matthew Prior, Joseph Whiting Stock, Susan C. Waters and others, illustrate the changing nature from irrefutable deathbed or mortuary depictions to posthumous portraits that showed the deceased living. The exhibition will refocus an appreciation of folk portraiture through the lens of memory and loss, highlighting the individuals whose identities are preserved through portraits made after death. Some artists dreaded such commissions, while others made it a regular part of their practice.

“The Children of Oliver Adams” by Deacon Robert Peckham (1785–1877), Bolton, Mass., 1831, oil on canvas, 26¼ by 21¼ inches. Collection of Charles N. Grichar. —Gavin Ashworth photo

The challenges were many as artists were charged with taking sketches and measurements from corpses, basing their portrait on earlier paintings or facial similarities to other family members. The subject then needed to be imagined as standing orengaged in some activity. The use of symbols and props such as roses and other symbolic flowers, toys and elements specifically associated with the deceased, color palette, sailing ships and sunsets, often indicated that the sitter was deceased. Many of these symbols have a duality of meanings that depend on their particular combination for a portrait to be understood as posthumous. The exhibition will examine these visual motifs and their meanings, much of which has faded over time.

The exhibition concludes with 78 postmortem daguerreotypes on loan from the Burns family collection dating from the 1840s to 1870s. The invention of photography in 1839 provided a new way to cheat death through the manipulation of the corpse to capture a “living” image of a loved one. The daguerreian operator vied for customers with the traditional portrait painter for a number of years and some families elected to commission both painted and photographic images. The emphasis slowly shifted from “sleeping” images to the unblinking reality of a corpse whose “hue of death” could not be disguised.

Early photographers adapted the slogan of the artist in paint when they warned customers to “secure the shadow ‘ere the substance fades.” The link between shadows and absence is an ancient one that speaks to the very origins of portraiture when a young woman of Corinth traced her beloved’s shadow on a wall to remain as a presence once he departed. Posthumous portraits and postmortem daguerreotypes are memories fixed in colored pigments on canvas and vapors on silver. And we cannot help but hear them whisper through the years, “remember me,” because, as photographer Mathew Brady declared in 1856, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.”

The American Folk Art Museum is at 2 Lincoln Square, Columbus Avenue at West 66th Street. For information, www.folkartmuseum.org or 212-977-7295.

[slideshow_deploy id=’1000275483′]