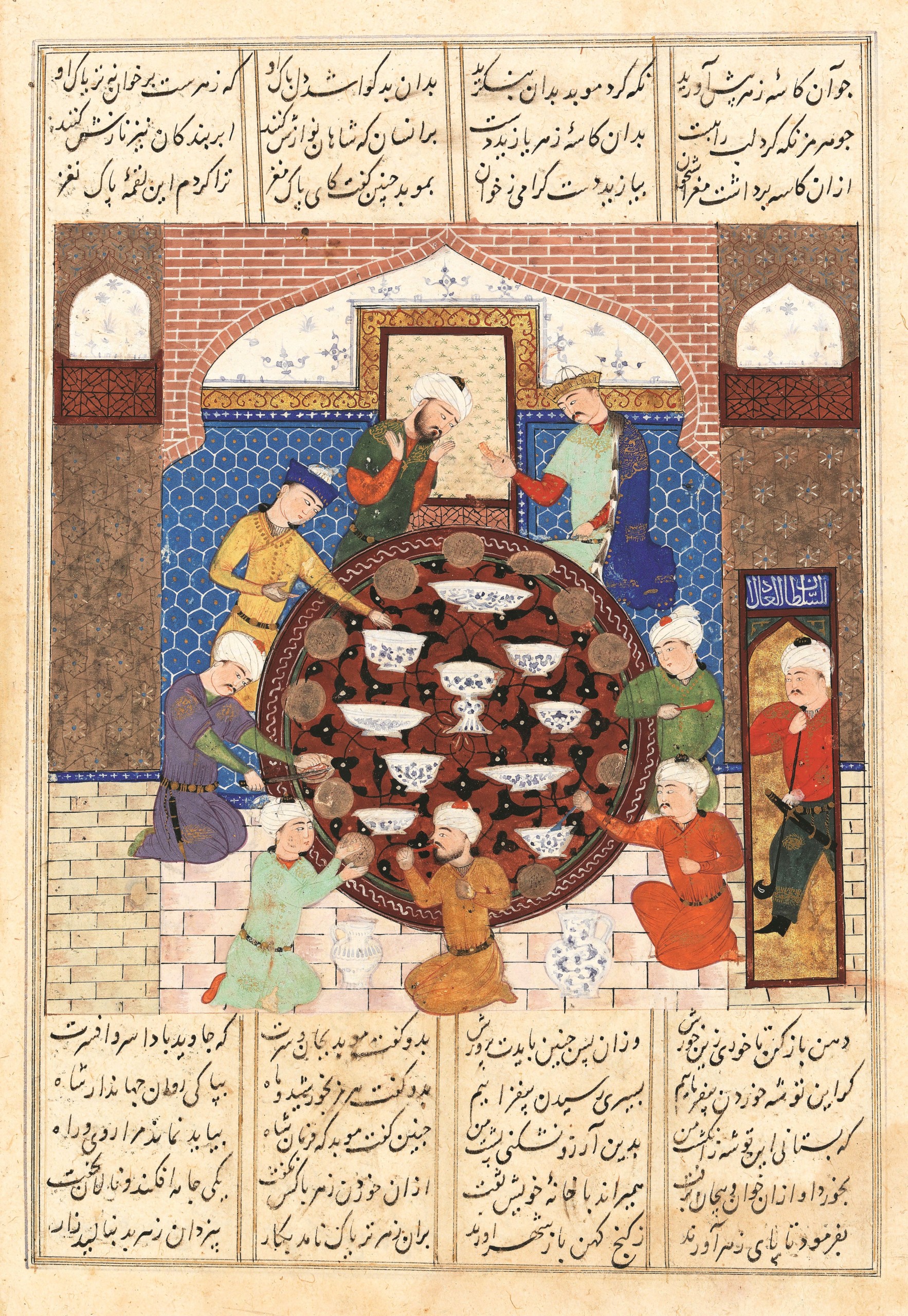

“A Banquet Scene with Hormuz,” folio from a dispersed manuscript of the Shahnama of Firdawsi, Iran, Shiraz, circa 1485-95, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky, photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA.

By James D. Balestrieri

LOS ANGELES — “Dining with the Sultan: The Fine Art of Feasting,” opening at LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), asks us to consider the possibility that eating — that is, communal eating when it is elevated to the level of ritual — might just be humankind’s first immersive art form. By centering this question on Islamic feasts from Moorish Spain to Mughal India, from the Ninth Century to the Twenty-First Century, through more than 250 objects that demonstrate the evolution of a variety of cuisines and influences ranging from Chinese porcelain to Yemeni coffee to dishes from as far afield as Venice, India and Mongolia, the exhibition offers insight into a web of intertwining, overlapping foodways.

What happens when we eat together? When we plan a meal? When we make a meal with others? Food is sensory, sensual, medicinal and intellectual — within cultures, it binds us, one to another; across cultures, it opens our minds and hearts to an otherness that suddenly, well, isn’t so other. This is the root of feasts on celebratory days, the reason for state dinners and diplomatic banquets. On the other side, food is power and wealth, its abundance controlled and doled out — food is, or can be, a projection of power. What would the appearance of ice at a feast in a desert say to a visiting ruler or emissary? What would foodstuffs — from far-off lands — in delicate vessels — from even farther away — say? Then the feast has and is a language all its own. It is a careful, aesthetic and artistic arrangement of signifiers: shapes, colors, smells, tastes, textures — add music, dance, recitation and sound enters the tent or hall — that means to convey intention. Even the humblest holiday meal is a moment of escape and, perhaps, of hope.

“Members of Court of Sultan Selim II (r. 1566-1574)” by Nigari, Turkey, circa 1570, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Edwin Binney, 3rd, Collection of Turkish Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo ©Museum Associates/LACM.

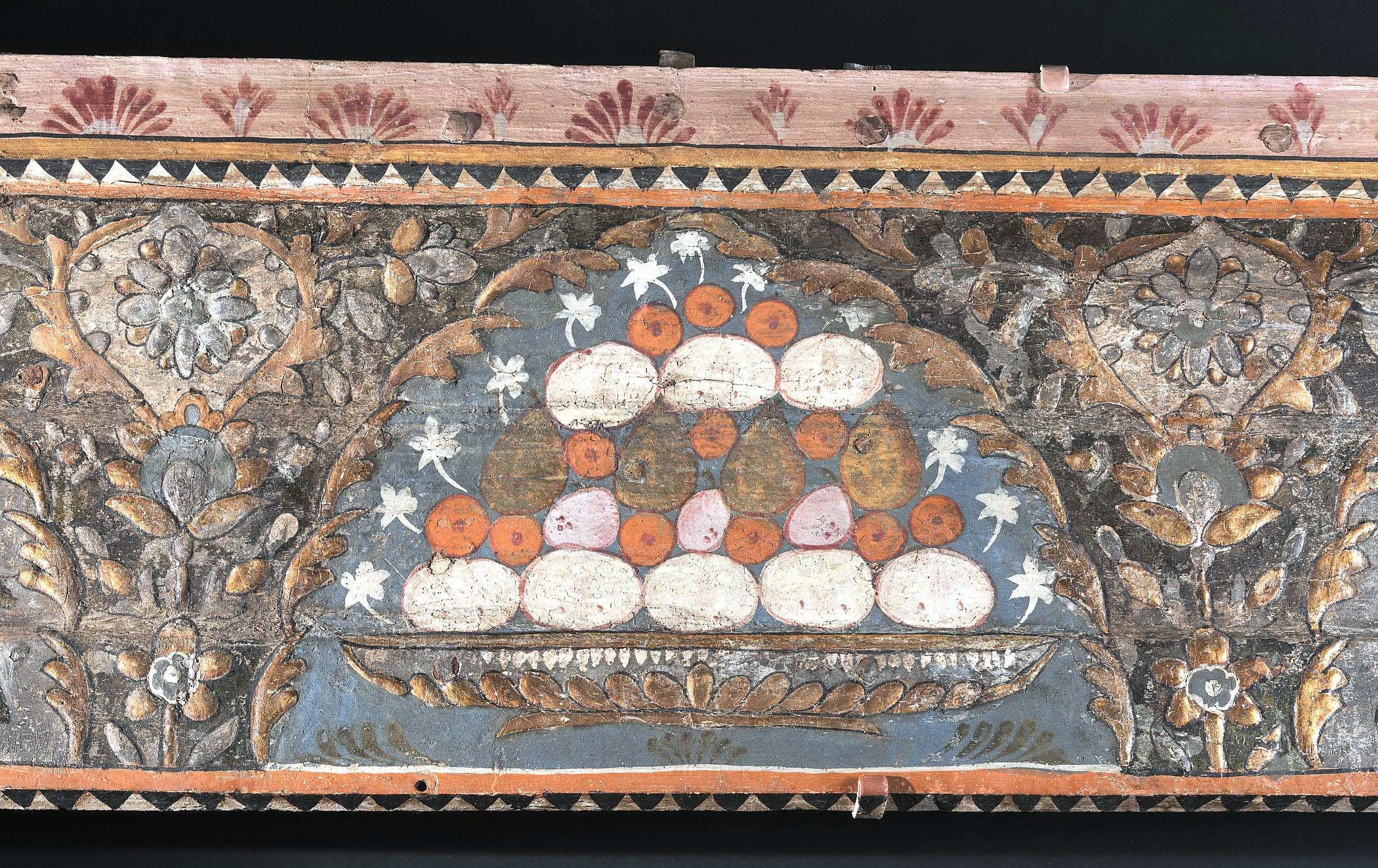

“Dining with the Sultan” ventures beyond museum objects, offering visitors a sensory glimpse, if you will, of the splendor of the Islamic feast. For example, Iranian American chef and author Najmieh Batmanglij will be on site, cooking dishes based on the rich culinary history — a history that includes an astonishing number of extant recipes, cookbooks, manuscript descriptions and images of food. Also, the exhibition includes a fully furnished and table-laid room, the Damascus Room, removed from an Ottoman-era home, that once served as a reception and dining area. To bring the exhibition into the present, artist Sadik Kwaish Alfraji’s installation incorporates taste, smell and touch into his memory of his mother’s breadmaking. The exhibition, like the excellent and enjoyable catalog, is laid out thematically, in courses. You move through it as if through a feast, from dynasty to dynasty, from refinement to refinement. As a bonus, recipes that sound scrumptious are sprinkled throughout the exhibition and catalog, like so many rare stigma and styles of saffron in broth. Think there of how quickly we substitute one sense — “sound” — for another — taste — when taste is impossible, and yet, our desire to experience creates an instantaneous synesthetic transference. One recipe in particular, judhabat al-mishmish (apricot judhaba) — that dates back to the Ninth Century reign of the Caliph Al-Wathiq — leads to a roast chicken served over an apricot, saffron and rosewater-flatbread that heats in the pan under the falling chicken juices. Judhabat al-mishmish will absolutely make an appearance in my kitchen one of these days. I’ll report back.

It’s worthwhile to go back to the beginning, before the feasts, and to relate the evolution of a single, crucial dish: tharid, meat cooked in broth with crumbled bread on top, that was a favorite of the Prophet Muhammad. Over time, to honor the Prophet, many recipes for tharida emerged, some with redolently spiced meatballs, others cooked with pomegranate juice or with eggs in milk and butter. This last version from a Maghrib (North African and Spanish) cookbook simply called Manuscrito Anónimo highlights the humor that permeates the exhibition and Islamic culinary history. As Charles Perry writes in A Canvas of Cuisines, his contribution to the catalog, “This lacto-ovo alternative to stewed meat is a bit surprising, but even more of a surprise to us is the fact that medieval cooks were going to all the trouble of making puff pastry just in order to crumble it into stew. Strange indeed; but would they ever have stumbled on the puff pastry idea without this arbitrary motivation? This leads us into deep thoughts about the historical process. In any case, the Maghribis did become aware of musammana’s potential as a pastry” (p. 37).

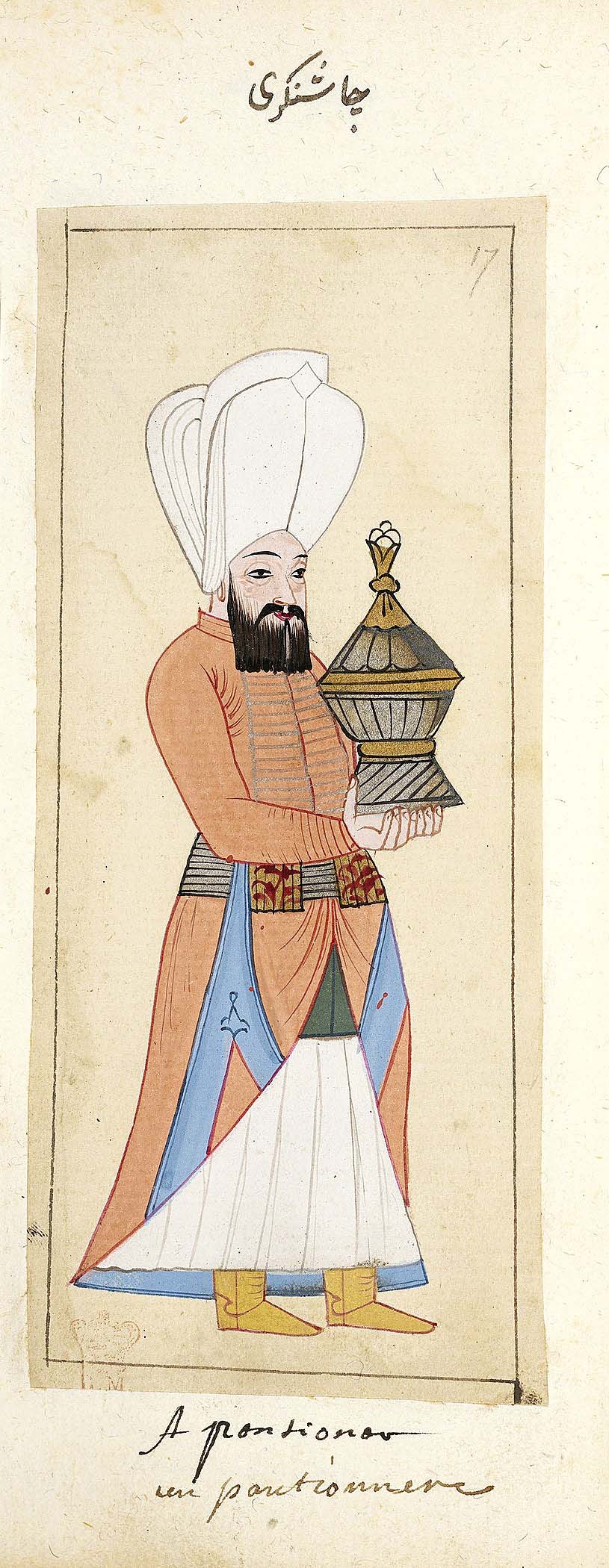

“The Taster (Çaşnigiri),” folio in the album The Habits of the Grand Signor’s Court, Turkey, circa 1620, British Museum, London, bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane, 1928, photo ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Food even becomes a subject for parodic, poetic debates (Wine vs. Beer, as an example) created by “gastronomic poets,” whose role at court was to celebrate the gustatory munificence of the ruler through verses and stories surrounding his feasts — I almost wrote “feats” just there, in what was perhaps a not-so-Freudian slip equating the banquet with the chivalric deed. In Noodles vs. Rice. In The Story of Muza’far and Bughra, by Bushaq At‘ima, the Fifteenth Century gastronomic poet of Shiraz, muza’far, a dish of saffroned rice demands tribute from Bughra, a dish of noodles simmered in broth. Each lines up his warrior allies and a pitched battle ensues. Now, in order to appreciate the parody, the reader or listener — who would have known this then — has to understand that noodles (think couscous) are indigenous through the Middle East. Wheat, after all, was a staple of the so-called Fertile Crescent. Rice, however, was an import, probably from the Indian subcontinent, a luxury that became a kind of preferred staple. Here is an excerpt: “As Muza‘far stepped onto the field, sweet as syrup and the color of garlic, in fear of harm he put toasted bread in front of himself and began to boast: ‘I am the adorner of the table on holidays. I give joy at weddings, and I console the bereaved. From me light comes to candles, of me midday meals are made. If a bird were to come forth from the egg of me it would pluck out Bughra’s eyes.’ When Bughra heard this, he too drove his steed into the battlefield, a spear of tamarisk over his shoulder. ‘I am stronger than any soup; in stew, I am yellower than any egg yolk. I redden the face like rose petals; I bring sweat to forehead and cheeks. I enter bit by bit from head to foot, not like rice, which sticks in the throat. If you are healthy, cook stew with me. Only the ill look for rice and lentils. I am the food of manly men. Rice is womanish and cowardly.’” (p. 59) In the end, however, the courtly Muza’far vanquishes the streetwise Bughra; rice takes its rightful place above noodles in the gastronomic hierarchy.

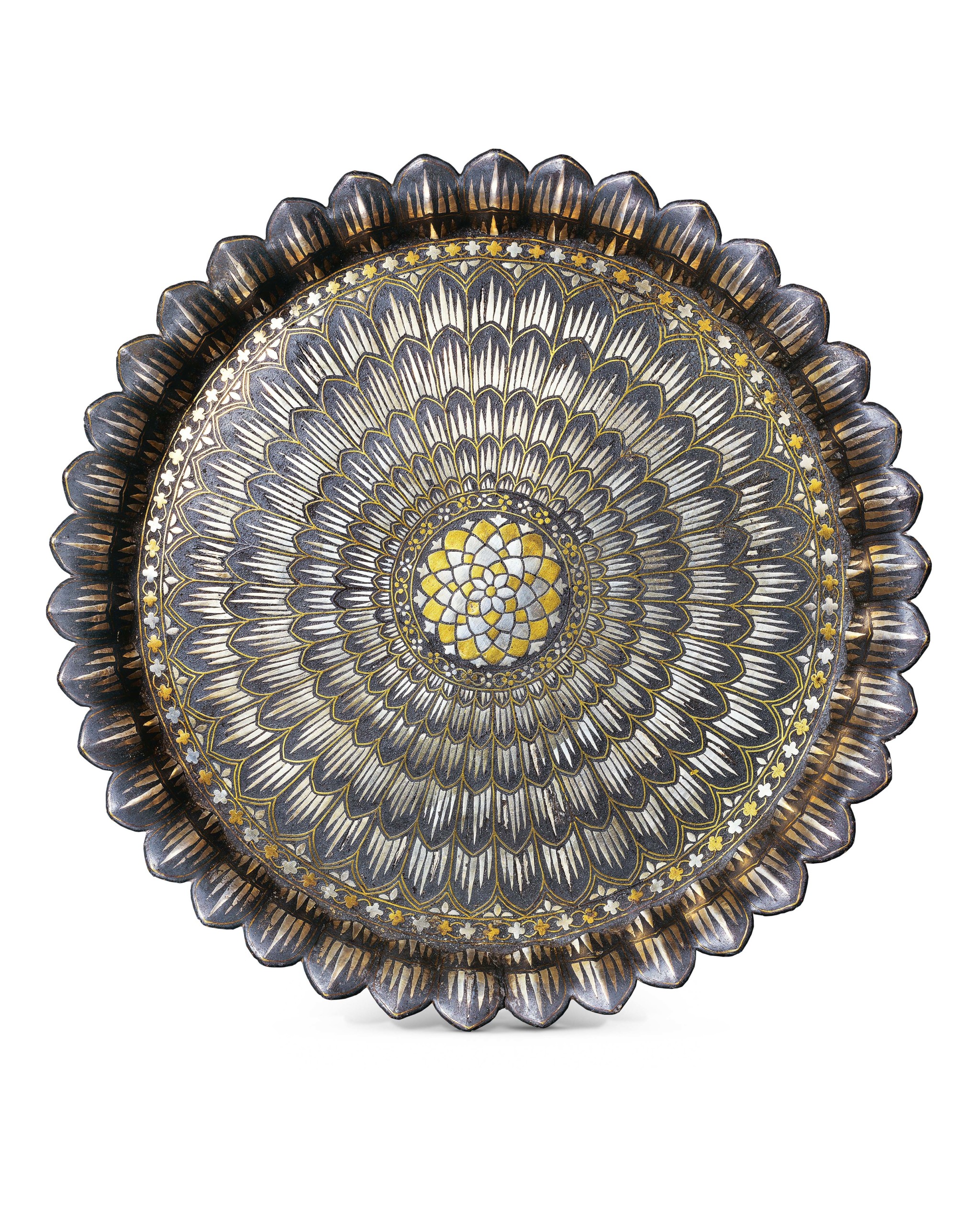

Footed dish, Turkey, Iznik, late Sixteenth Century, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, photo ©Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar.

The incorporation of exotic goods into preparing and serving dishes follows on from the assimilation of foodways. The Umayyad empire, centered in Damascus, adopts Egyptian spices and flavors to dishes from Mecca and substitutes grape wine for fermented dates. Persian influences, especially in the form of sweets and sweet-sour dishes enter Islamic cuisine when Abbasid empire builds its capital Baghdad. At the same time, blue and white porcelain, imported from China, spreads like wildfire. Apart from the sheer beauty of painted china, porcelain neither stains nor taints the food it holds. And it can be fashioned into any number of shapes for any number of uses, from single serving dishes to large storage containers. Rulers and the wealthy would create elaborate displays of china and would sometimes borrow or lend pieces for special occasions. It wasn’t long before blue and white china began to be made by Islamic potters and for the wares to be made more readily available outside palace walls. Mamluk sultans “seemed to love fowl and horse meat, while the later Ottoman empire preferred fish, light pastry and more subtle flavors” (p. 51).

Bowl, Iraq, Ninth-Tenth Century, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Descriptions of actual feasts in the exhibition approach the mythological. Thousands of animals, caravans of vegetables, fruits and spices were transformed into dozens of complex dishes designed to balance the humors in the body, “blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. These humors corresponded to the qualities of dryness, dampness, cold and heat that underlaid all earthly substances and inhered as special qualities in foodstuffs” (p. 47). Seating charts were filled with meaning — who was seated where and where they had been seated before told tales of favor and disfavor. Textiles to sit on and use as napkins and tapestries that fell from the walls and ceiling, orchestrated by color and texture, created an atmosphere of splendor, as did performances designed to accompany the meal. At the same time, etiquette manuals cautioned diners to eschew gluttony and to watch out for the gourmand who eats all the dates and drops the pits in front of you when you’re not looking, just to make you look bad. With so much food, I fretted about waste and kept asking myself, “What happened to the leftovers?” But the exhibition and catalog satisfied even this craving to know. Leftovers often went to servants and their families or were packed in boxes marked with the ruler’s crest and sold in the streets. The rest was often doled out to the poor.

Flask, India, Deccan, Sixteenth-Seventeenth Century, The Farjam Collection, photo courtesy of The Farjam Collection.

Before closing, a word about coffee, which came from Ethiopia to Yemen and became a ritual beverage among Sufi mystics, transporting them even as it transports most of us on most mornings. As Islam gradually forbade wine and beer, coffee took the place of alcohol in ritual conviviality. Coffee houses sprang up across the Middle East and soon made their way to Europe via Vienna and other points of contact between the Christian and Islamic worlds. The aroma of roasting, grinding and brewing coffee led to specialized cups, pots, trays, coffeehouses and pastries — puff pastries among them — designed to accompany what has become, for many of us, our essential elixir.

It is in our nature to ritualize, to make arts of activities, even those simple acts — like eating — that sustain us. Therefore, a feast is a feat just as cuisine is perhaps the ultimate in cultural borrowing. Think about it. You cook, following a recipe or heading out on your own. You don’t have what you need and find a substitute, or you decide that you just might have a better idea. You take a pinch of this, a dollop of that, experiment, appropriate and come up with a synthesis that, in the end, transcends and even forgets its origins. It might be slumgullion and end up in the bin; it might be something that becomes tradition in your family, your community, your country. It might leave nothing but a trace, a trace you leave but never know. And so, with all the arts.

“Dining with the Sultan: The Fine Art of Feasting” will be on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Arts until August 4.

Los Angeles County Museum of Arts is at 5905 Wilshire Boulevard. For information, 323-857-6000 or www.lacma.org.