This “show home” opened at Disneyland in 1957 to encourage the use of plastics in interior design and to position Monsanto as an industry leader. While the Monsanto House was reimagined over the years, this particular rendering was never realized. Rendering for Monsanto House of the Future by Eileen J. Aureli, circa 1958. Gouache on tissue. Collection of Jill A. Wiltse and H. Kirk Brown III. Photograph courtesy of Denver Art Museum.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

MILWAUKEE, WIS. – Designers Charles and Ray Eames famously observed, “Toys are not really as innocent as they look. Toys and games are preludes to serious ideas.” The momentousness of fun and frolic in Modernist design, a perhaps surprising idea at first take, is the subject of “Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America.” Co-organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum and the Denver Art Museum, this presentation will delight visitors from September 28 through January 6 in Milwaukee before traveling to Denver in 2019.

Monica Obniski, the Demmer curator of Twentieth and Twenty-First Century design at the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM), and Darrin Alfred, the curator of architecture, design and graphics of the Denver Art Museum, highlight designers who developed lighthearted home décor, fashioned special toys or imbued corporate identities with a whimsical spirit. We learn through the exhibition and catalog that these were not mutually exclusive groups. These co-curators pay special attention to lesser-known designers – for example, Henry P. Glass (1911-2003), Gene Tepper (1919-2013) and Bradbury Thompson (1911-1995) – while also spotlighting such Hall of Famers as Charles Eames (1907-1978), Ray Eames (1912-1988), Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) and Harry Bertoia (1915-1978). Obniski stated, “in mounting an exhibition on Modernism, we decided that we would take a specific viewpoint, focus it through a specific lens. Then we could do the topic justice.”

Factors driving the rise of “play” in the design process during the late 1940s, 1950s and 1960s included a reaction against uniformity and a need for emotional release at the conclusion of World War II, the desire to provide a nurturing environment for the surge of young ones who arrived in the postwar years, and educators’ and parents’ continuing interest in the connections between childhood play and learning, an area that John Dewey and others had begun to investigate earlier in the century.

Recognizing the relationship between improvisation and innovation, designers engaged in play in their studios and workshops as a way to trigger ideas. For example, Charles and Ray Eames made movies of tops and toy trains, put on impromptu theatrical performances using masks they had collected on trips abroad and tinkered with the “Solar Do-Nothing Machine,” among other experimental objects, the last bringing to mind the mobile, dazzling installations of contemporary artist Nick Cave. Particularly in the 1950s, this practice was glorified, captured in photographs and on film and discussed in articles and books as never before.

Collectors and students of Modern design, as well as the simply nostalgic, can savor some 270 exemplary items in this offering. The eclectic assemblage includes renderings, maquettes, film segments, advertising materials, furniture, textiles, tableware, toys, playground equipment and even Latin American folk art. Suggestive of the range of art and artifacts showcased are the innovative wall clocks designed by Irving Harper (1916-2015) for the Howard Miller Clock Company; Eva Zeisel’s (1906-2011) fanciful bird-shaped tea set for Monmouth Pottery; the Magnet Master 400 toy construction set, the brainchild of architect and designer Arthur A. Carrara (1910-1991); and samples of the packaging Paul Rand (1914-1996) dreamed up for El Producto cigars.

Asked to point to a favorite aspect of the exhibition, Monica Obniski selected the Dallas Love Field Airport VIP lounge Alexander H. Girard (1907-1993) designed for Braniff Airlines in 1965. It stands as an illuminating illustration of the corporate embrace of play. Obniski told how Braniff was a conservative airline before hiring Girard to revamp its image. For the VIP lounge, Girard juxtaposed Herman Miller interlocking display units and textiles of his own design, both Modern in style, with examples of international folk art. “This became the insignia of the design firm… I think that it will be new and exciting for museum visitors to think about folk art as decoration in Modern interiors.” Obniski reflected further, “When people think about ‘Midcentury,’ they think about the IBM building and ‘The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,’ but there were designers taking risks and adding levity to corporate approaches.”

Asked to point to a favorite aspect of the exhibition, Monica Obniski selected the Dallas Love Field Airport VIP lounge Alexander H. Girard (1907-1993) designed for Braniff Airlines in 1965. It stands as an illuminating illustration of the corporate embrace of play. Obniski told how Braniff was a conservative airline before hiring Girard to revamp its image. For the VIP lounge, Girard juxtaposed Herman Miller interlocking display units and textiles of his own design, both Modern in style, with examples of international folk art. “This became the insignia of the design firm… I think that it will be new and exciting for museum visitors to think about folk art as decoration in Modern interiors.” Obniski reflected further, “When people think about ‘Midcentury,’ they think about the IBM building and ‘The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,’ but there were designers taking risks and adding levity to corporate approaches.”

On a parallel track, between 1956 and 1960 the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) hosted the Forecast advertising and design-invitational initiative to promote novel applications of aluminum in architecture and design. The enticing kick-off ad for the campaign read, “Forecast: There’s a world of aluminum in the wonderful world of tomorrow… rich in comforts, eye-delighting in color and form. And so Alcoa will present a broad collection of outstanding designs, to be shown in pages like this one. They will let you glimpse the lightness and brightness and beauty of aluminum that will come into your home and into your life… in the wonderful world of tomorrow.”

Among the prototypes publicized were an accordion camping trailer by Henry P. Glass, occasional tables by Isamu Noguchi, modular buffet serving ware by Don Wallance (1909-1990) and the previously mentioned “Solar Do-Nothing Machine” by the Eameses. The Alcoa Forecast program is represented in the exhibition by more than two dozen sketches, objects and advertisements, and in the catalog by Darrin Alfred’s intriguing essay.

The scholarly, yet accessible, catalog, with its zippy, Pop design and multitude of striking illustrations, embodies the topic perfectly. It is fresh in both look and approach. While some writers on Modern design skate along the surface and never move beyond vague commentary, the co-curators and other contributors to the “Serious Play” catalog have conducted deep research as the basis for their directed essays. As an example of their method, they combed through designers’ writings, interviews and oral histories while also drawing upon the more commonly referenced renderings and products.

Queried about the most important lesson the exhibition has to offer, Obniski pointed to “the constructive and valuable quality of play.” She went on to explain, “In 2018, America is not a happy society. We work hard. We value work, but we don’t value play in the same way.” After touring this exhibition, “visitors might be encouraged to take 15 minutes a day to draw or to let their mind wander. These designers were not grinding out designs for the perfect chair. They were playing with colors; they were taking photographs. These were aids in creativity.”

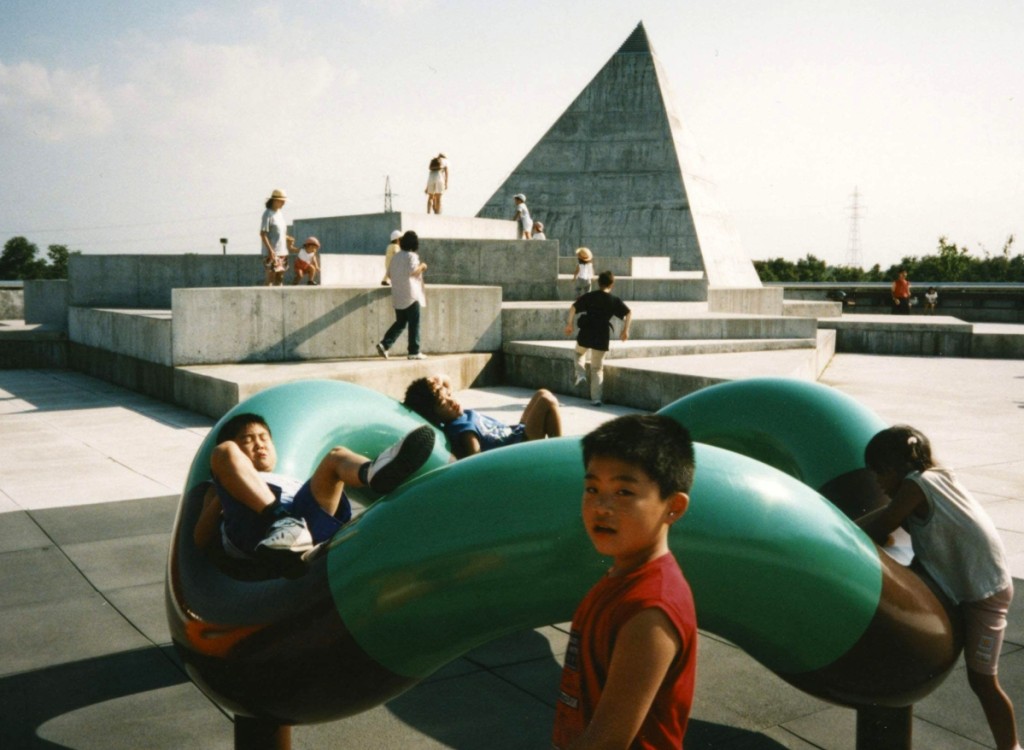

Moerenuma Park was completed in 2005, 17 years after the death of its designer Noguchi. “Play Sculpture” by Isamu Noguchi, Moerenuma Koen (Moerenuma Park) in Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan, n.d. Photographer unknown. ©The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Considering decorative arts and design a natural avenue for connecting with people, the MAM curator described participatory activities and play areas created in conjunction with the exhibition. Cards similar to those the Eameses used in their “House of Cards” set have been decorated by community members and incorporated into “structures” on display. In a hands-on area, visitors can work with a version of the Tyng Toy, a group of modular shapes cut from plywood designed by Anne Tyng (1920-2011) and first offered for sale in 1949. Visitors will be able to assemble a rocking chair, a table or whatever suits their fancy. For the enjoyment of all, the museum has borrowed a usable play sculpture called “The Noodle” from the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. (Over a period of decades, Noguchi explored the realm of play landscapes and equipment specifically designed for play.) In addition, MAM will host “Build Days” for visitors. These enhancements are reminders that interactive learning at museums grew in part from the play and toy experiments concocted by designers of this era.

During the mid-Twentieth Century, a surprising array of designers in the United States tapped into the power of play in order to “prime the pump,” often with toys and games, domestic wares and corporate branding as the end products in mind. Exhibition visitors may be amazed to learn how opportunities for creative engagement, amusement and edification were artfully built into all kinds of objects designated for “unstructured play” a half-century ago. They likely will be buoyed by the spirit of American optimism inherent in these artifacts and will break into a smile when they think about the significance of play in American life.

In summary, “Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America” runs at the Milwaukee Art Museum from September 28 through January 6. The exhibition will then travel to the Denver Art Museum, where it can be seen from May 5 through August 25.

A catalog of the same title edited by exhibition co-curators Monica Obniski and Darrin Alfred is scheduled for release on October 23. Published by Yale University Press, it contains essays by Darrin Alfred, Amy Auscherman, Steven Heller, Pat Kirkham, Alexandra Lange and Monica Obniski.

.jpg)