“Symmetry No. 62” by M.C. Escher, January 1944. Colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of Michael S. Sachs. All M.C. Escher works ©The M.C. Escher Company, The Netherlands. All rights reserved.

By James D. Balestrieri

HOUSTON, TEXAS – M.C. Escher’s possible impossibles – possible in geometric terms, impossible in our reality – are so much a part of popular culture that we accept them without hesitation as they oscillate between mathematics and art, between orderly realities and fantastic dreams. Escher’s images graced the covers of 1960s-70s rock and roll albums and have inspired filmmakers from Christopher Nolan (Inception) to Peter Jackson (The Hobbit) to Scott Derrickson (Doctor Strange) to Hwang Dong-hyuk (Squid Game). Time and again, what Escher offers in his woodcuts is the sense of another world running beside, beneath or above ours, a world where the physical constraints are different or absent. In Escher’s world, gravity is challenged, infinity can be represented, incredible transformations are possible, and perception reigns over reality. His images of symmetries and infinities sensitize us, compelling us to tune in to rhythms and patterns in nature and in our daily lives that we have overlooked, missed or, perhaps, forgotten.

Curated by Dena M. Woodall, curator, prints and drawings, “Virtual Realities: The Art of M.C. Escher from the Michael S. Sachs Collection,” the new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is a comprehensive survey of the life and art of Escher. The exhibition is organized chronologically and thematically, beginning with the artist’s portraiture, student and early work, and his Italian pieces. Afterwards, Escher’s mature work, his tessellations, métamorphoses, works that transform two dimensions into three, reflecting worlds, Platonic solids, spirals in space, impossible buildings and representations of infinity will be on display. As well, visitors will see rare original artworks, wood and linoleum blocks, lithographic stones and the artist’s tools. Interactive rooms, where visitors may play with optical illusions, accompany the exhibition.

There is both a science and a fiction behind Escher’s woodcuts, yet they are neither science nor fiction, nor are they, in and of themselves, science fiction. You want to classify them as surrealist, yet Escher’s devotion to the idea of the “regular division of the plane” and the strange, relentless logic of his work makes any alignment with the surrealist drive to access the random unreason of the unconscious impossible. That fact that Escher never understood why his art was so readily adopted by the counterculture of the 1960s as “psychedelic” bears this out.

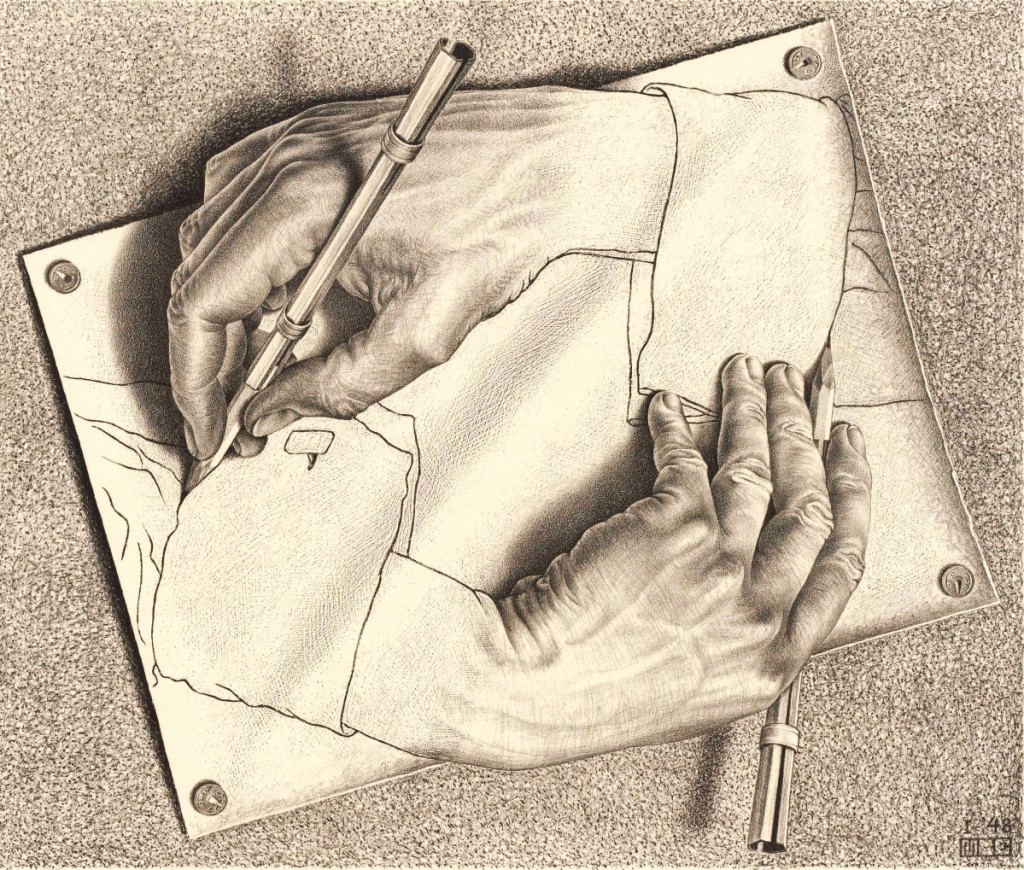

“Drawing Hands” by M.C. Escher, January 1948. Lithograph, 11-1/8 by 13-1/8 inches. Collection of Michael S. Sachs. All M.C. Escher works ©The M.C. Escher Company B.V.-Baarn-the Netherlands. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Just as Escher’s work isn’t surrealist – nor, obviously, is it realistic – it doesn’t really belong with modernism at all. There is no sense of mourning for the loss of order or meaning, no cubist or futurist or expressionist philosophy and process to replace the contours and tenets of realism with new rules for making art and for making meaning from art. Escher didn’t create to displace and supplant.

Following the exhibition’s lead, it’s worthwhile considering Escher’s early life and work, and the seminal moments that led to his mature works, which he called “mental images.”

Maurits Cornelis Escher was born in 1898 in the Netherlands. He studied in Delft and Haarlem, where he learned the art and craft of the woodcut, which would become the medium he preferred and perfected. In the 1920s, Escher traveled throughout Europe and settled in Italy, where he met his wife and started a family. Works from this period – landscapes, clouds and village scenes – show the artist’s interest in rhythm and repetition, concepts he would refine over time into the patterns and designs of his mature, famous woodcuts.

In an interview on the M.C. Escher website, Escher’s son recalls his father’s seriousness when he was conceiving a project, but also his sense of fun and play once a project was underway. He describes his father’s love of the patterns in nature and recalls the mazes he would make out of the furniture in the house.

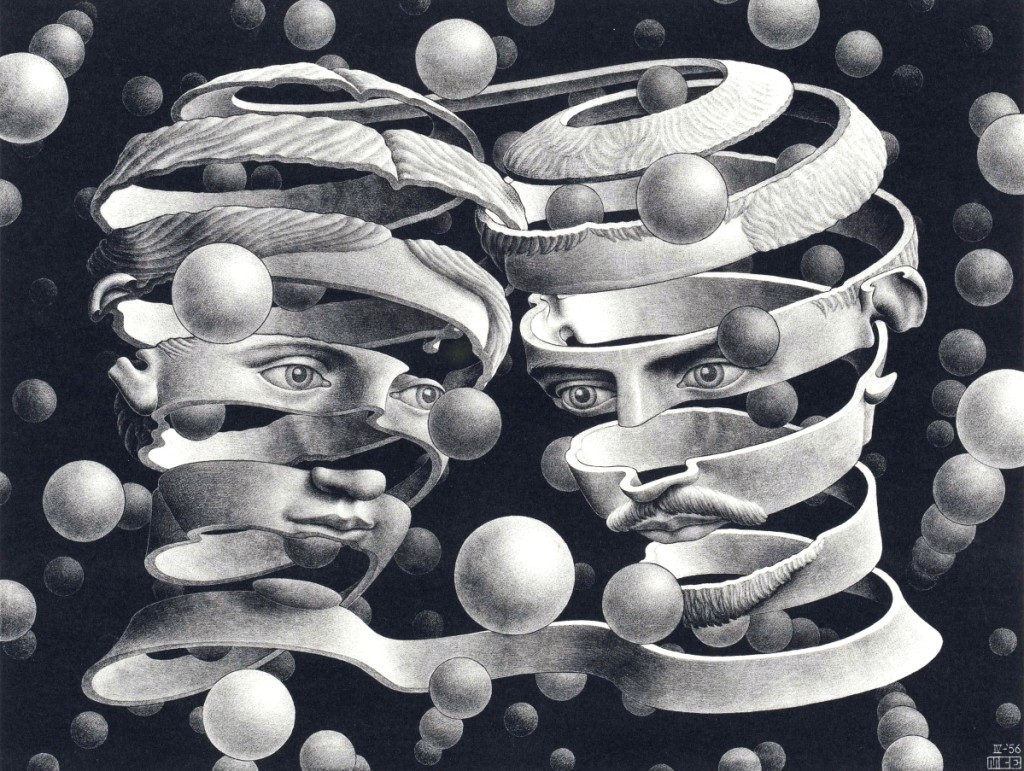

“Bond of Union” by M.C. Escher, April 1956. Lithograph, 10 by 13-3/8 inches. Collection of Michael S. Sachs. All M.C. Escher works ©The M.C. Escher Company B.V.-Baarn-the Netherlands. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Escher once said, “I don’t grow up. In me is the small child of my early days.” I would argue that this simple statement reveals a great deal about the artist. Much of Escher’s appeal can be found in the word “play”: play as in a game or contest – or maze, play as in a space that allows movement – one might also substitute the word “give” here – or play as movement itself, as in the “play of light.” Yet Escher’s play is nothing like the “playfulness” of postmodernism where verbal and visual games hold up ironic funhouse mirrors to a world in which meaning is suspect.

The complex geometries of the Moorish tiles in the Alhambra in Spain, which Escher toured in 1922 and 1936, led to a great leap in Escher’s visual aesthetic – the “play” of tessellations and transformations soon comes to dominate his practice. In one work, devils fill the spaces between angels while angels fill the spaces between devils. The balance requires no commentary; meaning, make itself even as the repeated images proliferate and the fill the picture plane.

In a famous 1938 woodcut, “Sky and Water I,” Escher grafts transformation onto tessellation as birds morph into fish or fish morph into birds – depending on how you read the image. Beyond that, from the top and bottom, the complexity of the single naturalistic bird and fish fall away into simplified shapes. The black birds against the white sky merge with the black sea, while the white sky congeals into white fish. Yet the naturalistic bird at the top has more white defining its details than any other bird; the same is true, conversely, of the naturalistic fish at the bottom. From left to right, the birds and fish fly and swim onto the image and out of it, breaking the horizontal lines that frame a softly rounded square that recalls a frame of film. The viewer grasps at notions of evolution, perhaps, but what is really evolving is perception – our perception.

“Day and Night” by M.C. Escher, 1938. Woodblock for tone. Courtesy of Michael S. Sachs. All M.C. Escher works ©The M.C. Escher Company, The Netherlands. All rights reserved.

Works from the 1940s, like “Reptiles” and “Drawing Hands” – perhaps the first Escher I recall seeing as a kid, one that made me think of two Warner Brothers cartoons where the characters take over as artists and torment one another with abrupt changes in costume, scenery and perspective, and liberal use of the eraser – move the artist towards themes of creation and representations of infinity. In “Reptiles,” the snorting creatures crawl out of a drawing in Escher’s notebook, moving from two dimensions to three as they circle through and over a still life of succulents and a book of matches that reads “JOB” – is Escher seeing his art as his job, or is there a reference to the Biblical Job, where the artist sees himself suffering for his art? Then, the reptiles crawl past a jug and glass -whiskey, perhaps? – and up and over a book of natural history and onto a bridge made of an artist’s triangle that overlooks an open journal and leads to a ten-sided solid, and a brass cup with cigarettes and more matches. At this point, the creatures crawl back into the drawing, moving from three dimensions to two. The entire lithograph is, of course, two-dimensional. It’s Escher’s “play” with perspective as well as the “play” in perspective that leads us round with the little beasts.

At times, Escher seems to be reminding us that nature doesn’t necessarily abide by the rules that we have deemed rules, and that those rules are, in large measure, matters of perspective and point of view.

“Bond of Union,” a 1956 lithograph, adds a note of spirituality to Escher’s interest in spirals in space and impossible infinities. Here, a couple staring into one another’s eyes become an infinite ribbon, an endless apple peel joined at top and bottom, hovering between their individual identities and a unified identity as a couple, somewhere between coming together and coming apart. They – though they are hardly a “they” – float in an undifferentiated black space. Bubbles float around and inside them like thoughts or unspoken words. The artist’s aesthetic tells a story of sorts – metamorphosis becomes metaphor.

A relatively late woodcut, “Path of Life III,” from 1966, exemplifies Escher’s interest in infinity. The bioformic “squid-birds,” tucked neatly one into another, regress infinitesimally in size towards the center of the image and flap at their largest round the edge. Overlaying the creatures, a geometric figure in red spirals in and out in a similar rhythm. The sensation, at first, is one of looking into a cone, but when you step back a bit, you feel that if you wrapped this image onto a sphere, the figures would join up and you could hold this infinite world in your hand.

“Möbius Strip I” M.C. Escher, March 1961. Wood engraving and woodcut in red, green, gold, and black, printed from two blocks, on paper. Courtesy of Michael S. Sachs. All M.C. Escher works ©The M.C. Escher Company, The Netherlands. All rights reserved.

Escher has always been difficult if not impossible to place in the story of modernism. Despite its claims to the radical breaking of old forms and the creation of new ones, modernism’s denial of perspective and subject is nevertheless a denial in terms of those qualities of art. You know what’s missing when you look at Pollock. Once he finds the “play” in perspective and subject, Escher proceeds as if their existence is a tool he can use however he wants. A fish is a form. Moreover, the idea of the “regular division of the plane” leads to the practice of filling the plane.

If it’s all in how you look at it, where “all” is the universe and “how you look at it” depends on your point of view, your perspective, it might be possible to define Escher as a fun sort of relativist and leave it at that. Too many mathematicians, however, such as Nobel Prize winner Roger Penrose have seen, in Escher’s work, visualizations of the concepts they strive to express in the language of math. Instead of symbols, living things – fantastic beasts and creatures – combine in Escher with geometry to create wonder without malice or mendacity. WE may marvel at the sheer complexity of a mathematical formula or an Escher print, though neither is intended to fool of dismay us. Quite the contrary. Each is meant to open our eyes to the infinite orders of order beneath the order we think we know.

“Virtual Realities: The Art of M.C. Escher from the Michael S. Sachs Collection” will be on view at the MFA Houston through September 5.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is at 1001 Bissonnet Street. For information, 713-639-7300 or www.mfah.org.