The sale’s highest price, $144,000, was earned by Shang Wheeler’s rare mallard drake, circa 1940, in an at-rest pose. Wheeler mostly carved decoys for his own personal use and this is believed to be the only sleeping mallard he made.

Review by Rick Russack, Photos Courtesy Guyette & Deeter

ST MICHAEL’S, MD. – The second of Guyette & Deeter’s three cataloged decoy auctions this year took place on August 6-7. The one word to sum it up would be “success.” Five lots sold for more $100,000 each and about 100 lots earned five-figure prices, with the two-day sale grossing $4.2 million. There were just over 500 lots offered, but the word “decoy” doesn’t really describe everything the sale included. Yes, there were duck and shorebird decoys from nearly every bird hunting region representing the East Coast to the West Coast. There were fine examples of sporting art, including an oil on canvas of duck hunters that was 5 feet wide. There were miniature carvings, decorative carvings, fish decoys and carvings, duck and turkey calls, ammunition boxes, some hunting firearms, some American furniture, and this is not a complete list. One of the most unusual offerings was a collection of 48 vintage falconry hoods.

We’re in an era in which most auctioneers have dispensed with thick catalogs filled with color photographs and details about what is being sold, relying instead on online descriptions, with more or less information, depending on the auction company. Decoy auctioneers are one of the exceptions to this practice. The catalog for this sale was about 350 pages long, sometimes with multiple photos of each item. Condition reports were included, and the accuracy of those descriptions was guaranteed. The catalog also included extensive biographies of some of the men and women whose collections were being sold, biographies of several of the major carvers and information about specific but perhaps little-known facets of the collecting or hunting world. For example, this catalog included a discussion of specifics of New England shore birds, a two-page explanation of falcon hoods, a discussion of the role played by the demand for feathers for women’s hats and the enormous slaughter it caused and more. Catalog descriptions often trace the movement of prize decoys from one famous collection to another. In other words, catalogs like this keep alive the “lore” of decoy collecting.

At $108,000, this fish decoy was one of the surprises of the auction. Hans Jenner carved and painted this walnut fish, a so-called “ghost fish.” Called by some “a fish on fish,” the painting on each side of the body is done in such a way as it appears a second fish is swimming alongside the larger one.

The sale started with carvings by contemporary carvers and the first lot, a willet in flight by William Gibian, sold for $19,200, almost five times the estimate – that’s a good way to start a sale. Interest continued strong in the contemporary carvers with a loon by Mark McNair selling for $10,800. There were five ducks by Jim Schmiedlin, one of the masters of the craft who died in 2015. Bringing $45,000 was a 2008 back-preening wood duck drake with fine paint and details, such as carved feathers, wingtips and tail. Its head and crest were tilted to one side and the drake was grooming itself. Schmiedlin, who developed Lou Gehrig’s disease late in life, sold this bird through a 2013 Guyette & Deeter auction, where it sold for $26,450, with the proceeds donated to the “Live Like Lou” foundation.

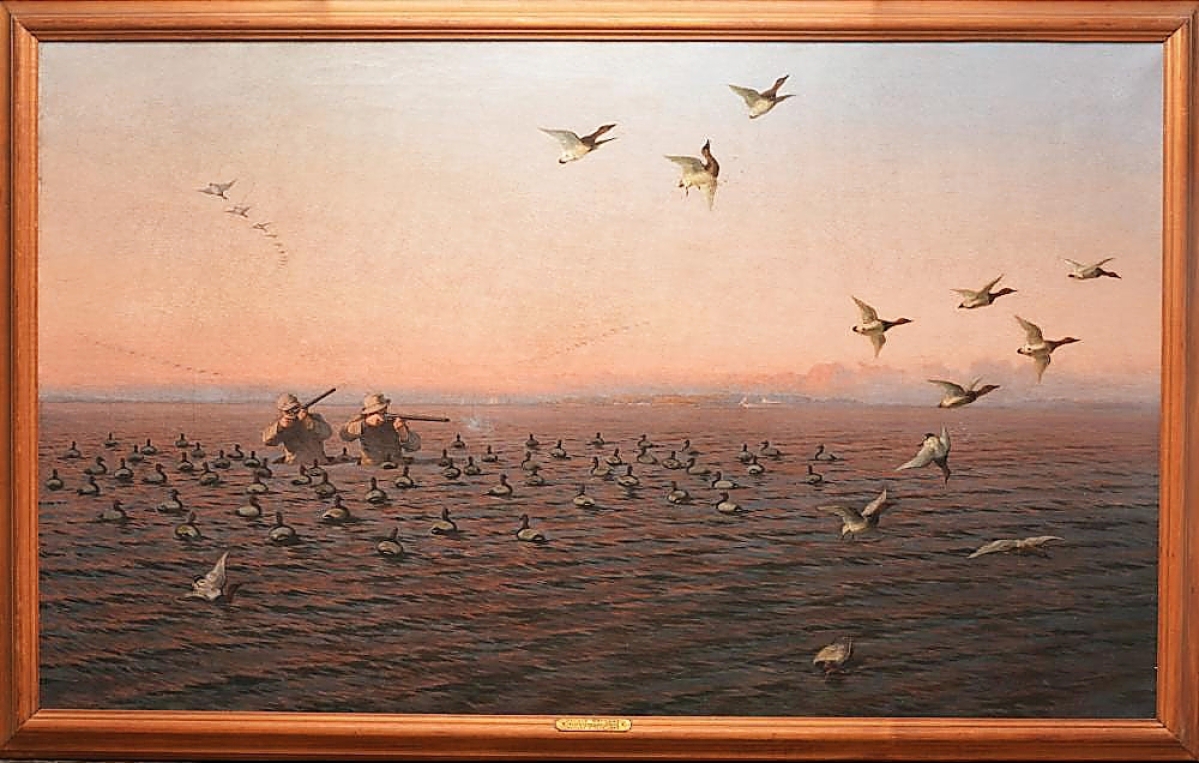

The first of the auction’s six-figure sales was an oil on canvas by Herman Gustav Simon (1846-1897). The large painting, 3 by 5 feet, which brought $102,000, was titled “Double Battery Susquehanna Flats” and was a scene of two well-dressed hunters rising from a sinkbox in the midst of a large rig of decoys. Canvasback ducks fly overhead and some, having been shot, are falling. The painting is thought to be the earliest and largest depiction of the use of the double sinkbox in the region and was, undoubtedly, originally destined for an affluent home. Herman Gustav Simon, born in Germany emigrated with his family, settling in Philadelphia. He was well-known in Philadelphia for his landscapes and paintings of animals. His work was included in several exhibitions in Philadelphia, including the 1876 Centennial Exhibition.

Use of the sinkbox, giving hunters a huge advantage, was a complicated undertaking, involving several small boats and several men to get everything safely set up and ready. It was not an inexpensive day’s sport. In 1905, renting the sinkbox and the necessary men for arranging everything could cost $100 (equivalent to $3,000 today). The catalog includes a reprint of an 1886 article published in Baltimore which discusses use of sinkboxes.

A large oil painting, illustrated by a fold-out plate in the catalog, was expected to be one of the stars of the sale and it was. Done by Herman Gustav Simon and selling for $102,000, it was titled “Double Battery Susquehanna Flats” and was a scene of two well-dressed hunters rising from a sinkbox with canvasback ducks flying overhead.

The sale included numerous other pieces of sporting art, including a painting by Edmund Osthaus (1858-1928) depicting two English setters on point, which earned $60,000. An oil on canvas by George Browne (1918-1958) depicting a flock of geese landing on a farm pond earned $12,000. It wasn’t necessary to spend five figures on good examples of sporting art. Several other works sold for less than $2,000, with some selling under $1,000.

Shang Wheeler’s rare mallard drake, circa 1940, in an at-rest pose with its head reclined to one side and its bill tucked under a wing, was expected to bring the top price of the sale, and it did not disappoint, realizing $144,000. It’s the only sleeping mallard by Wheeler now known to exist. Wheeler, who carved only for his own use, worked in Stratford, Conn., and most of his decoys represent species that frequented that area. Mallards were not common in the area and Wheeler did not make many. This particular decoy is pictured on page 70, as well as on the rear dust jacket, of Shang by Dixon Merkt. Wheeler gave it to a private family, where it has been since then; it has never been on the market prior to this sale. The catalog devotes four pages to a discussion of this decoy.

Four of the five lots that realized more than $100,000 were decoys but not all were expected to reach that level. One of the surprise finishers in the six-figure category (and it wasn’t the only one) was a Nantucket plover by an unknown maker, and another of the surprises was a fish decoy. Shorebirds accounted for several of the higher prices of the sale.

Of the five lots that sold for more than $100,000, two were shorebirds, one from Nantucket and this one from Long Island. It was a greater yellowlegs in a contented pose carved by William Bowman in the late Nineteenth Century. Well carved and well painted, it sold for $108,000.

The plover by an unknown Nantucket maker, dating to the late Nineteenth Century, had a high estimate of $22,000 but finished at $114,000, despite the fact that it had a professionally replaced bill. It had relief wing carving and near original paint. The catalog noted that it is a rig mate to the only Nantucket plover in the collection of the Museum of American Folk Art. Storms at sea would sometimes drive huge flocks of plovers to the island and hunters took advantage of that fact. A resident of the island reported that on August 29, 1863, 7,000 to 8,000 plovers and Eskimo curlews were killed on that one day. The birds were saved from extinction by legislation. In all, there were five other plovers by Nantucket carvers that sold between $2,400 and $7,800. The latter had four different holes for its supporting stick, meaning that it could appear to be in four different poses. A set of six plovers from nearby Martha’s Vineyard sold for $9,600.

Also finishing at the top of the list was another shorebird, this time a greater yellowlegs in a contented pose, which reached $108,000. It was one of a group of shorebirds from Long Island. This one had been made by William Bowman, who worked in the Nineteenth Century in Lawrence. It had its original paint, relief wing carving and extended wingtips. Another Bowman shorebird, a dowitcher in a resting pose, finished at $60,000. Obediah Verrity was another skilled Long Island carver, and his oversized whimbrel went out for $21,600.

There were far more than just shorebirds. A mallard drake by John Blair Sr, Philadelphia, dating to the late Nineteenth Century, earned $96,000. It had been illustrated in two books and had been included in an exhibition of Delaware River decoys. There were a number of decoys from the collection of D.C. North, who had specialized in Southern decoys. Many decoys from his collection have been pictured in a number of books, and this one appeared in three. It was a rare bufflehead carved by Virginia’s Arthur Cobb. Not many bufflehead decoys were made – they were not favorite targets of hunters as they were not as tasty as other species. This may be the only surviving bufflehead by Cobb, and it sold for $54,000. A tern decoy carved by Long Island’s Daniel Demott, which had been illustrated in two books, reached $45,000.

This mallard drake by John Blair Sr was a well-known example, having been pictured in two books. It more than doubled its estimate, bringing $96,000.

Terns were one of the birds almost decimated by the feather trade, intended to adorn women’s hats. Good Housekeeping magazine, in its 1886-1887 issue, reported “at Cape Cod, 40,000 terns have been killed in season by a single agent of the hat trade.” It also stated that an “enterprising” New York businesswoman on Cobb’s Island, Va., bagged 40,000 seabirds to meet the demands of a single hatmaker. Three pages of the catalog go into details of the feather trade.

Although some of the higher priced decoys in this sale have been highlighted, it would be a mistake to believe that all decoys are expensive. A circa 1900 yellowlegs shorebird decoy by New Jersey carver Lou Barkalow sold for $540; a canvas Canada goose decoy by Mannie Haywood sold for $600; a coot by Virginia carver James R. Rowe sold for the same price, and there were dozens more. Guyette & Deeter conducts weekly online-only decoy auctions with many birds selling under $1,000.

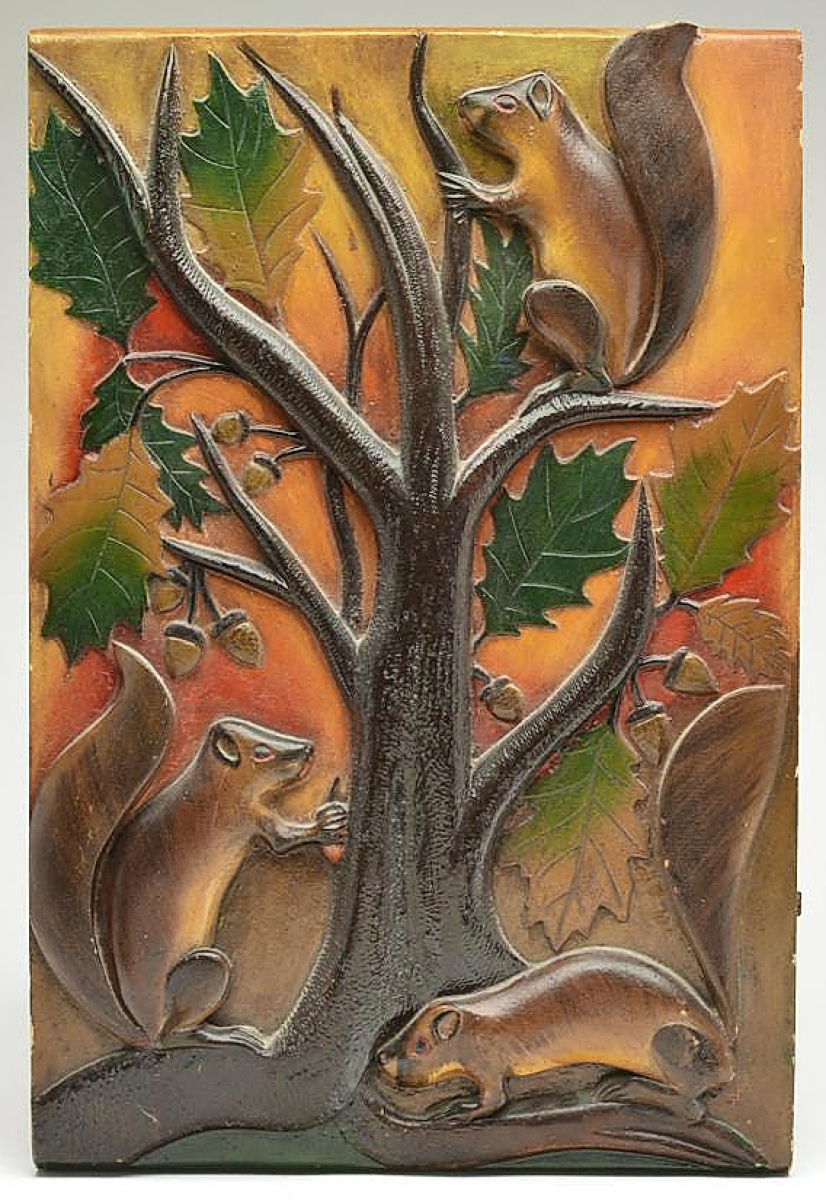

The name Oscar Peterson is often associated with fine fish decoys and there were several of his carvings, fish, plaques and even a goose. But it was a fish carved by Hans Janner, Mount Clemens, Mich., circa 1930, that sold for $108,000, more than three times the estimate, and one of the five highest priced items in the sale. Jenner was truly a “character,” so disliked even by members of his own family that when he died, his son burned so many of his decoys that today it’s estimated that only about 150 survive. The catalog devotes four pages to Jenner and his fish decoys. The one that brought top dollar was a 13-inch carved and painted walnut fish, a so-called “ghost fish.” The painting on each side of the body is done in such a way as it appears a second fish is swimming alongside the larger one. Called by some “a fish on fish,” it’s extremely rare. A rock bass decoy by Jenner earned $75,000, and another rock bass earned $63,000; each well over estimates. Oscar Peterson was represented by a number of carvings; a wall plaque with three squirrels in a tree gathering nuts sold for $69,000.

Oscar Peterson is best known for carvings of fish decoys, but he also carved other objects. One of his most unusual works was a wall plaque with three squirrels in a tree gathering nuts, which sold for $69,000.

A few days after the sale, Jon Deeter noted the strong market reflects the influx of new collectors. “We’re seeing dozens, sometimes more, new customers with each sale. And we’re seeing that collectors who began buying at our last few sales have continued to participate. That’s really great to see. We’re also seeing that level of interest across the board. Fish decoys are coming into their own, as they should. And buyers are realizing that there’s more to a wonderful decoy than a famous name of who made it. I’m thinking of the Nantucket plover by an unknown maker that brought more than $100,000. It’s good to see the level of participation we’re seeing now.”

Prices given include the buyer’s premium as stated by the auction house. Guyette & Deeter’s next sale is scheduled for November and will be conducted live (barring unforeseen circumstances) in conjunction with the Eastern Waterfowl show in Easton, Md.

For additional information, www.guyetteanddeeter.com or 410-745-0485.