“Lanterns” by William Charles Libby (American, 1919-1982), 1945, tempera on board, 27-1/8 by 17¾ inches. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Gift of Mr and Mrs James H. Beal, 63.1.5 Photograph ©2023 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Penn.

By Karla Klein Albertson

SHELBURNE, VT. — Pursuing an important single theme, Shelburne Museum’s exhibition, “All Aboard: The Railroad In American Art, 1840-1955,” is focused on a span of more than 100 years in American history when artists captured images of the outside and inside of rail travel. People of all ages have a favorite train memory from picking Dad up at the station to waiting at a flashing crossing to circling Disneyland as a kid. Even though passenger travel between cities has undergone significant change, try to navigate life in California’s Bay Area, Chicago or along the East Coast, without rails.

Abroad, from London to Tokyo, driving is never the answer, especially when trains designed for speed have been put into action. The Orient Express makes an intriguing film, but modern travelers focus on arrival, not place settings.

As for freight, there are underpasses and overpasses, but, at night, you can hear the subtle shift in background tone as hundreds of linked cars slide across the country with the essentials of daily life locked in stacked containers. They pass only blocks away, right now. No painters are waiting but railroads live on.

Thomas Denenberg is the John Wilmerding director and chief executive officer of the Shelburne Museum. He is one of the forces behind the traveling exhibition, “All Aboard: The Railroad in American Art, 1840-1955,” which is organized in concert with the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tenn., and the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Neb.

“All the Live Long Day” by Joe Jones (American, 1909-1963), 1939, oil on paper mounted on board, 16 by 29-5/8 inches. Art Gallery of Hamilton; Gift of Mr Herman H. Levy, O.B.E., 1961. Mike Lalich photo, 2017.

When the show opens first in Vermont for a June 22-October 20 run, it will be accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog available from the museums and online. Denenberg authored the final chapter, “Passengers All: People on the Train in American Art, 1900-1950.”

That section is filled with depictions of people riding and waiting for passenger trains as well as images of the workers that built and maintained the lines. Illustrations include the diverse below-ground riders in “The Under World” circa 1909-10, by Samuel J. Woolf (1880-1948) and “The Subway” 1919 by Walter Pach (1883-1958).

Speaking with Antiques and The Arts Weekly about the origin of this collaboration, Denenberg mentioned a previous joint project by the Shelburne and Dixon in 2017 titled “Wild Spaces, Open Seasons” that focused on hunting and fishing in American art. He explained: “Painters were advocates of the rugged outdoor life. We were used to looking at these very broad themes. Looking for another, we decided the railroad hadn’t been explored for a number of years. As we developed the idea, it was clear that artists — from the 1830s and 1840s on — developed a fascination with that technology. And they participated in promoting the railroad.

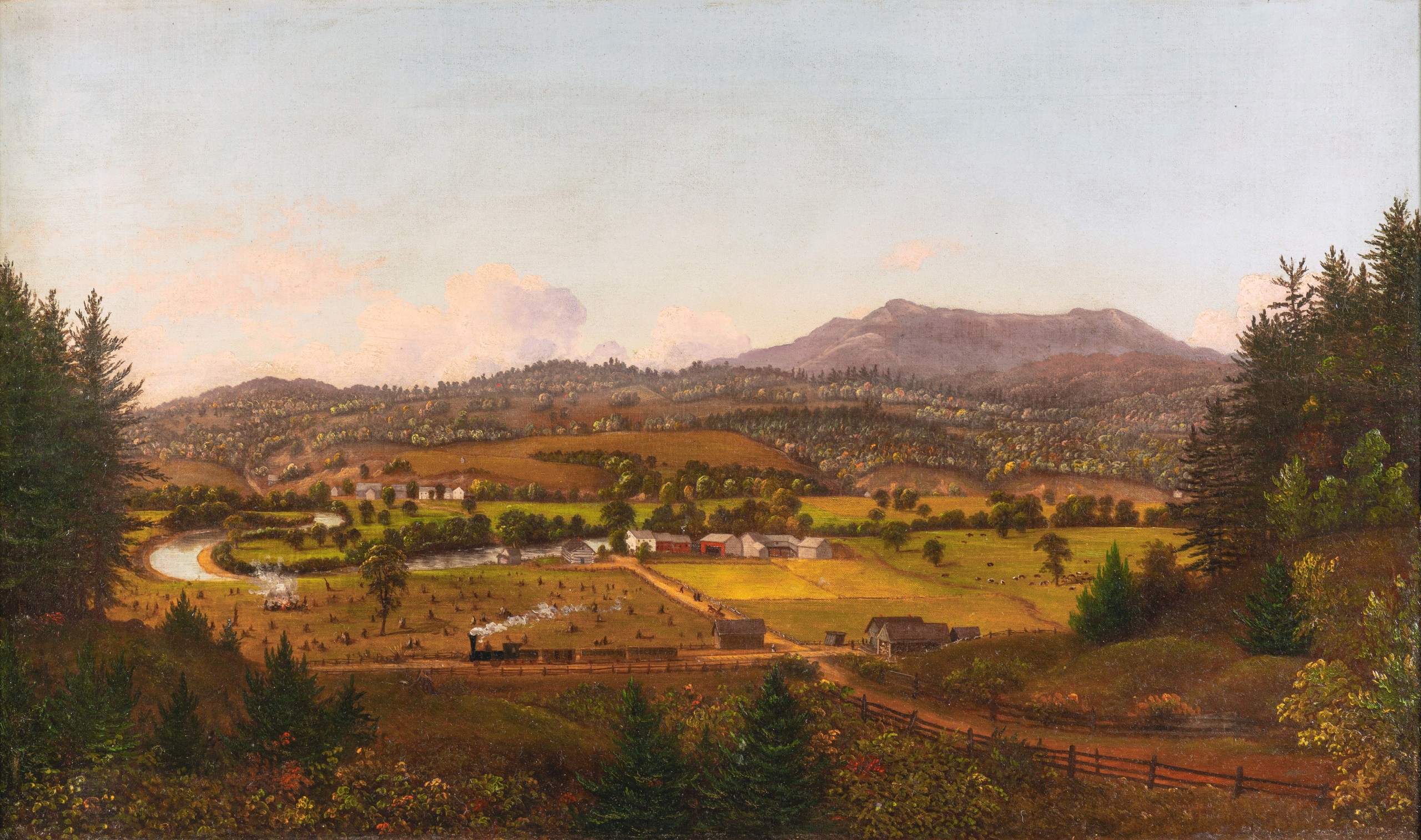

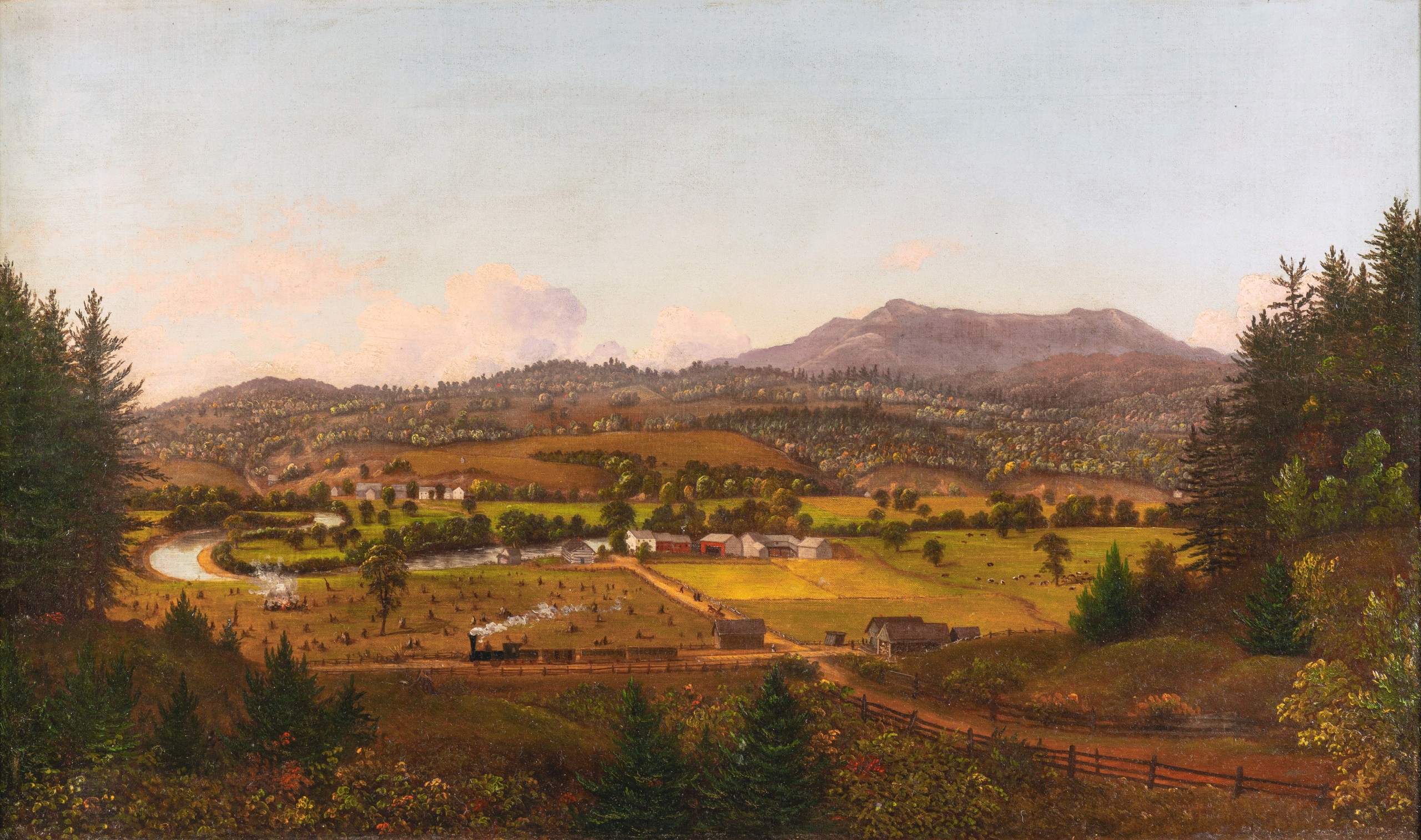

“Steam Train in North Williston, Vt.” by Charles Louis Heyde (American, 1822-1892), 1850, oil on canvas, 20-9/16 by 35-3/16 inches. Shelburne Museum; Gift of Edith Hopkins Walker, 1959-49.1. Photography by Andy Duback.

“By the 1860s and 1870s, you have numerous well-known artists who are commissioned by railroads to create this kind of visual culture of the West, as basically Eden. In this, the creative participated with capital and technology really from the Civil War into World War II — that seemed like a fascinating story. We thought the role that painters played in making railroads part of American culture was all-important for this story.”

Denenberg himself grew up in the era when many rail lines were shutting down and stories were published about the last trains to various destinations. As the national highway system expanded, vacations revolved around the family car or ever-cheaper air travel. Railroads were no longer revolutionary transportation. He pointed out that, now, “It’s an interesting moment, particularly where we are in Vermont. Train tracks literally bisect the campus at Shelburne Museum. And the state of Vermont has made a great effort to bring back passenger rail — Amtrak — in the last few years. I don’t know if it’s going to shock anyone, but I think the conversation about rail travel in our neck of the woods when you can get one train a day to New York City is so unlike the experience in Europe. Even small cities have wonderful rail service.”

When asked what he hopes visitors will take away, the director replied: “There are multiple themes to the exhibition. It starts with a section on when trains first appear.” (This is covered by the first catalog chapter, “Smoke in the Wilderness.”) “Then we talk about the industrialization of America and the progressive era. The element of nostalgia is important, as well.”

“Steel Valley, Pittsburgh” by Otto Kuhler (American, 1894-1977), circa 1925, oil on canvas, 45 by 50 inches. The Westmoreland Museum of American Art; Gift of Mr Richard M. Scaife, 2004.2.

Julie R. Pierotti, Martha R. Robinson curator, Dixon Gallery & Gardens, Memphis (the second institution to host the show), is editor of the catalog and author of that chapter on “Industry and Urbanization: The Railroad and American Art in the Progressive Era and Beyond.”

Early in the catalog, she writes, “By 1902, railroad tracks in the United States measured 200,000 miles, double what they had been just two decades prior, and technology was advancing as well, allowing trains to move more and more passengers and materials ever more quickly toward a growing number of destinations across the country. And while the railroad was crucial to America’s rise as a global economic leader, there were concerns, presciently articulated by Thoreau in the 1850s, over the costs of such progress to the nation’s landscape, well-being and identity.”

How did he write about this conflict of nature and industrial expansion?

Men have an indistinct notion that if they keep up this activity of joint stocks and spades long enough all will at length ride somewhere, in next to no time, and for nothing; but though a crowd rushes to the depot and the conductor shouts “All aboard!” when the smoke is blown away and the vapor condensed, it will be perceived that a few are riding, but the rest are run over ― and it will be called, and will be, “A melancholy accident.” Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854).

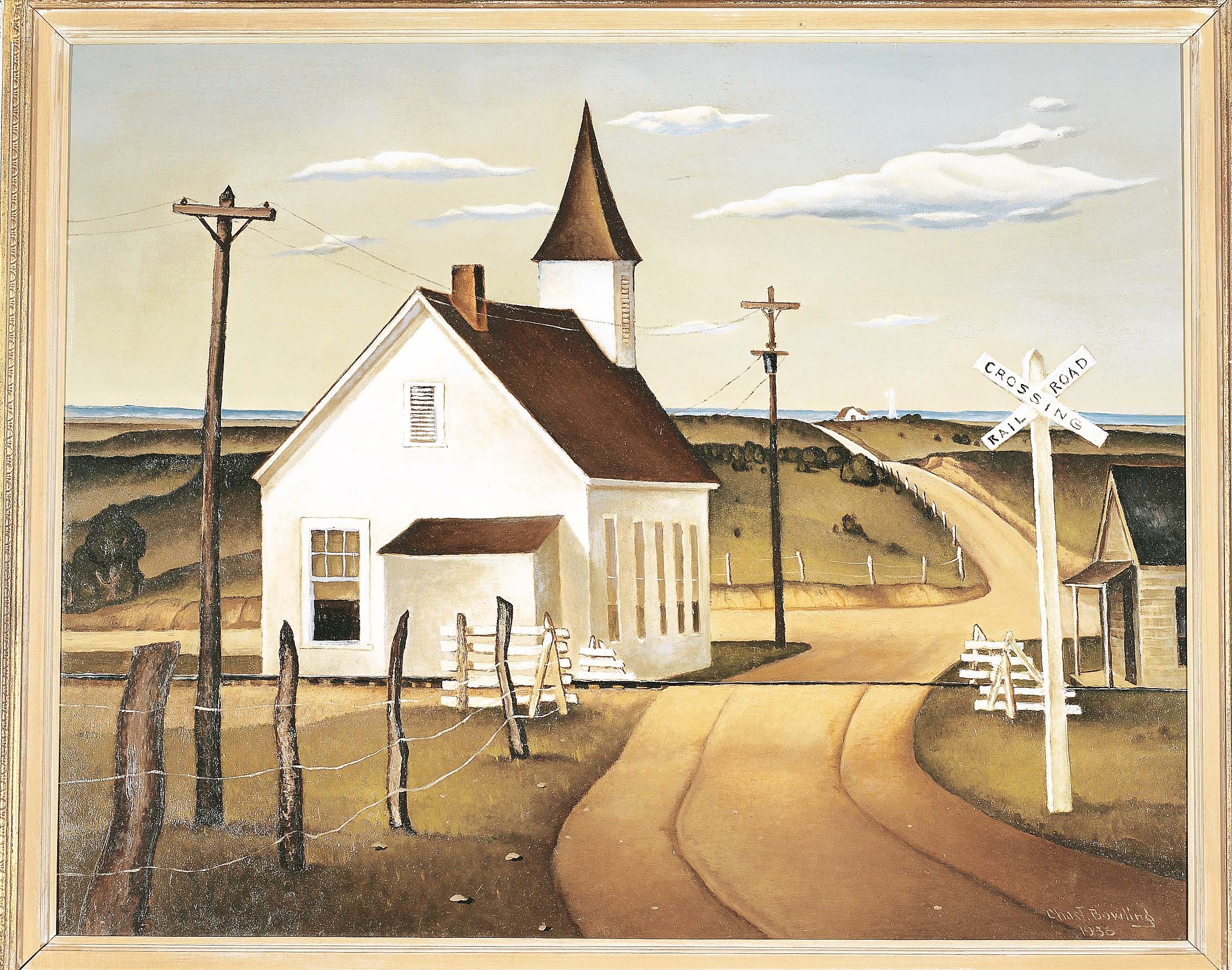

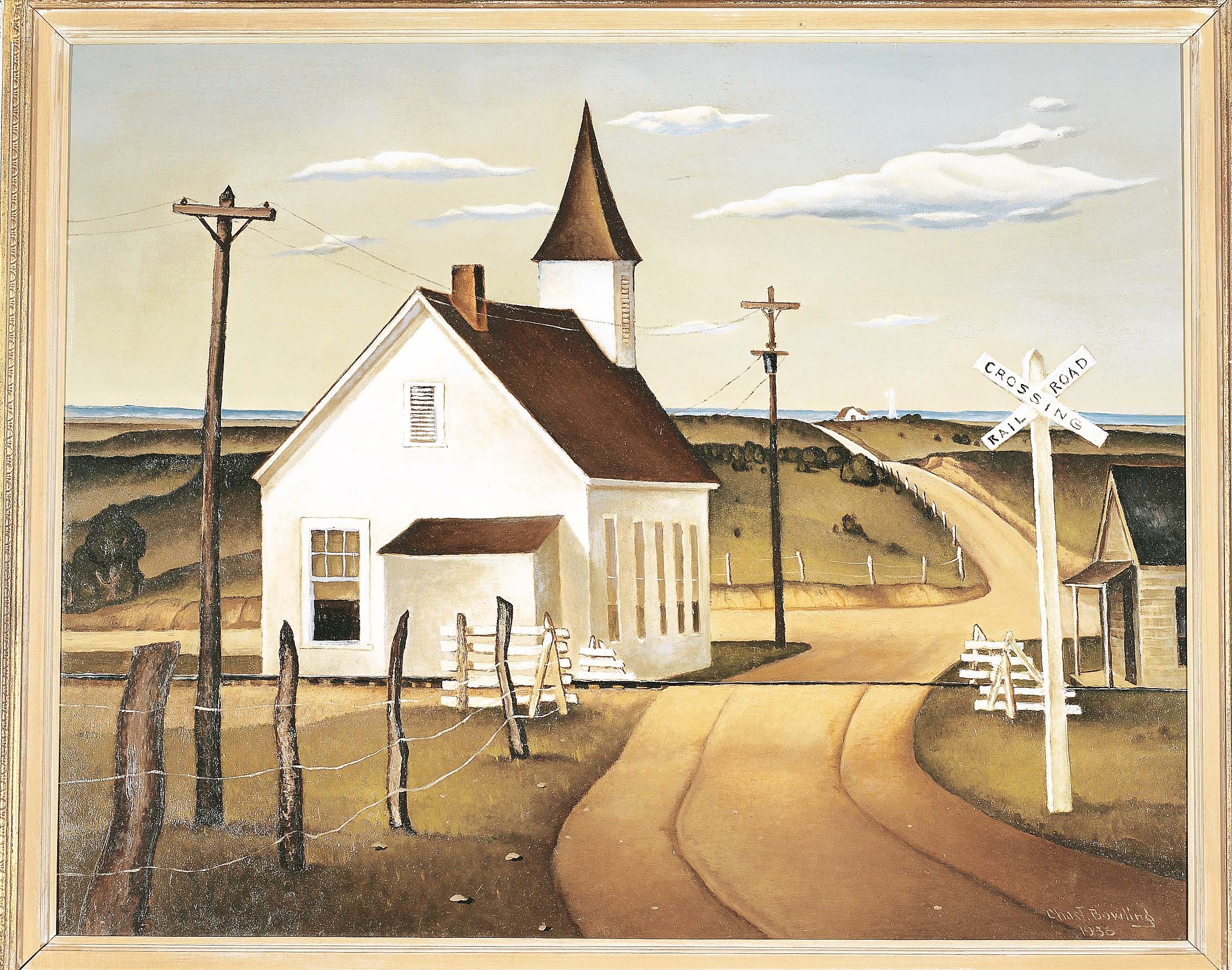

“Church at the Crossroads” by Charles T. Bowling (American, 1891-1985), 1936, oil on board, 24 by 30 inches. Anonymous, courtesy of the Dallas Museum of Art.

Pierotti’s contributions to the entire project were significant. She explained to Antiques and The Arts Weekly, “I took over writing this essay as the deadline approached and ended up being the point person for the catalog. It was a pleasure to do it — it was a wonderful project to work on. All the authors were great. We’re working with two other institutions, there has to be someone that makes sure everything is getting done. And I’m very happy how the show came together.”

She explained that the Dixon Gallery’s director, Kevin Sharp, had been wanting to do a show about trains for a long time. And visitors to the estate will remember that the train runs not very far from the edge of the institution’s expansive, multi-level garden campus. “He had this idea about the evolution of the depiction of trains in art and at the same time, the evolution of American art, for years, almost as long as I have known him. We started gathering images together well before the pandemic, so it’s been years in development.”

Pierotti continued, “My goal was to trace the evolution of the perception of trains and also illustrate the evolution of American art. In the first section, where we have the Hudson River School paintings, the train is being called the “devilish iron horse” — this huge monster that is creeping into the otherwise pristine wilderness. As the show moves forward through time, it becomes the engine of American industry which fuels American growth, especially urban growth. As you get into the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century, it becomes less of a curiosity and becomes this ubiquitous thing in American life, almost like it’s always been there.”

“River in the Catskills” by Thomas Cole (American, 1801-1848), 1843, oil on canvas, 27½ by 40-3/8 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Gift of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815-65, 47.1201. Photograph ©2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Then at the end of the show, it’s become sort of old-fashioned and there’s a nostalgic air about trains. By the 1950s, it was more about planes and cars. Visitors will go on that journey with us as they view the art beginning with Thomas Cole’s awe-inspiring “River in the Catskills” (1843). One hundred years later, the art shows pollution everywhere — grime and smoke and ash — because of the railroad and the industry it supports.”

The curator concluded, “The glamor of trains — and the excitement around them — had faded at a certain point. They became more an everyday thing. We’re not saying trains are dead but the fascination around them has abated.”

What better way to revive that excitement and fascination than “All Aboard” — the exhibition and catalog — as it, like the great engines it depicts, makes its way across America.

“All Aboard: The Railroad in American Art, 1840-1955” will be on view at the Shelburne Museum from June 22-October 20. Following its presentation in Vermont, it will travel to the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tenn., (November 2-January 24) before reaching its final stop at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Neb. (February 15-May 4).

The Shelburne Museum is at 6000 Shelburne Road. For information, 802-985-3346 or www.shelburnemuseum.org.