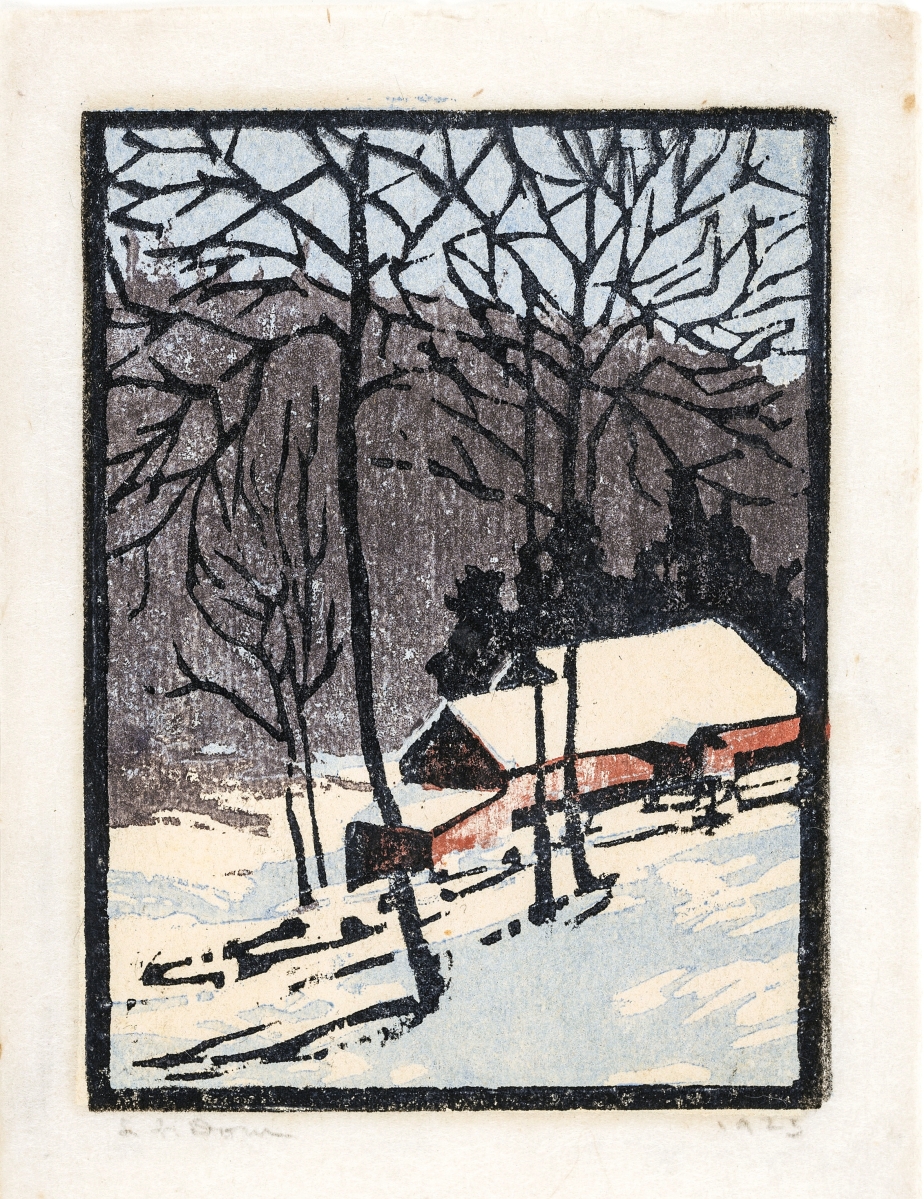

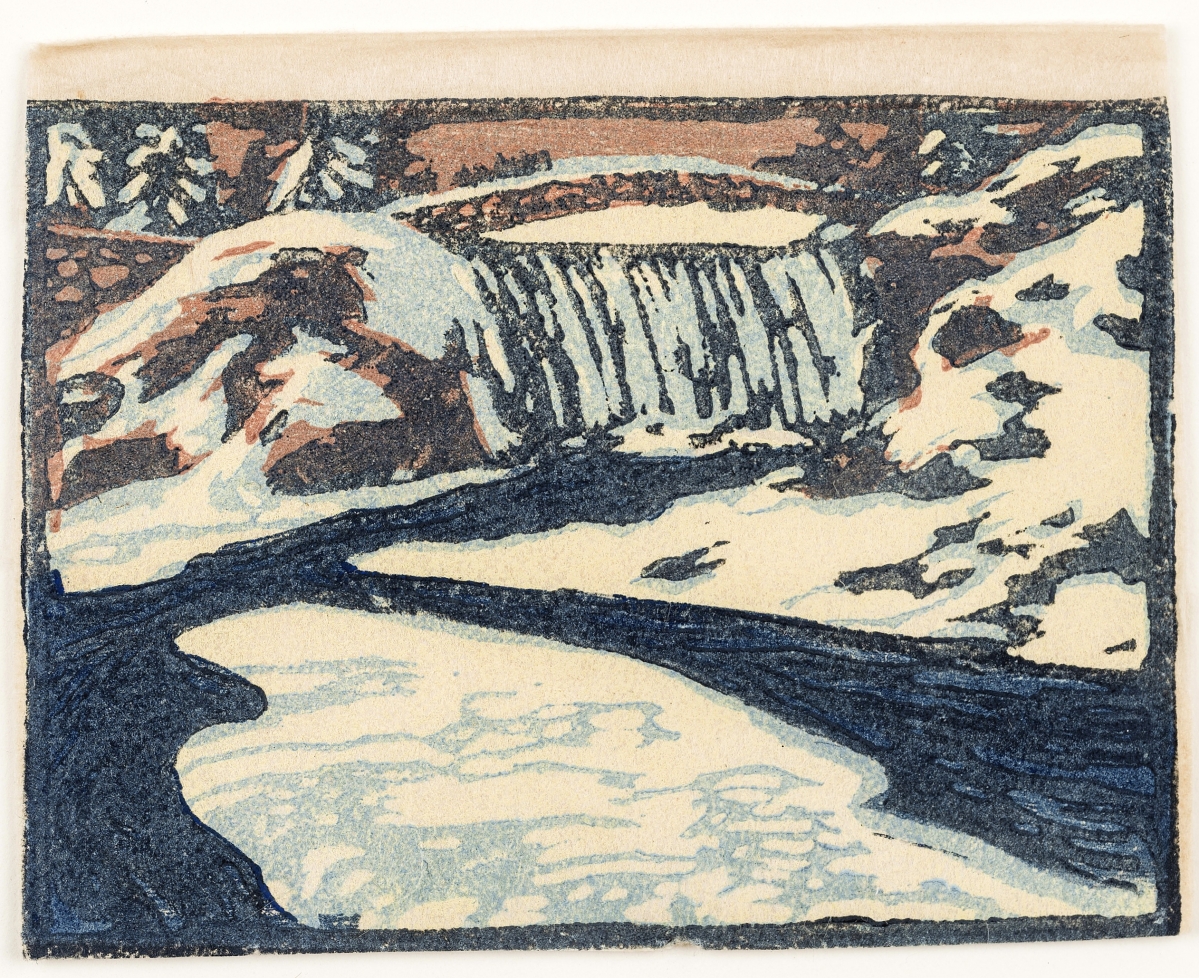

“Winter Falls” by Leo Francis Dorn (1879-1964), n.d., woodblock print, unsigned. Private collection.

By Kristin Nord

SILVERMINE, CONN. – Comradery and a shared commitment to artistic growth and excellence were at the core of Connecticut’s three art colonies during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries. While both the Cos Cob and Old Lyme colonies have become well known for the role they played in American Impressionism, the lesser-known Silvermine Art Colony, situated at the intersection of Wilton, Norwalk and New Canaan, had a different clientele and mission. Now, in “The Silvermine Art Colony and its Founding Members,” up through April 30 at the New Canaan Museum & Historical Society, this collegial group is finally getting its due.

Co-curators Susan Gunn Bromley and Edward Volmer have assembled an impressive survey of works by this highly diverse and eclectic group. The intent is for this exhibit to put the colony on the map, once and for all.

“What drew artists to the Silvermine area in the early 1900s was, in many ways, the same things that drew architects to New Canaan in the midcentury,” Nancy Geary, the New Canaan Museum and Historical Society’s executive director, commented, “Beautiful topography, land that was relatively inexpensive and proximity to New York City.”

Among the early founders was Solon H. Borglum (1868-1922), a renowned sculptor of cowboys and animals of the West. He trained in Paris in the 1890s and had exhibited there at the Salons. When he returned to the United States, he settled into a small working farm in Silvermine with his French wife and children. Other founders who would form the nucleus of the colony included Borglum’s good friend, Addison Thomas Millar (1860-1913), already acclaimed for his Orientalist paintings and etchings; Edmund Marion Ashe (1867-1941), a painter and illustrator for New York-based newspapers; Henry Grinnell Thomson (1850-1937), a painter of detailed still lifes; Howard L. Hildebrandt (1872-1958), a nationally recognized portrait, flora and landscape painter; his wife, Cornelia (1876-1962), an award-winning miniaturist, and William A. Boring (1859-1937), an architect and the Dean of Columbia School of Architecture. Nearly all completed formal training in prestigious art academies in the United States and Europe and had already worked in other art colonies.

“The Serenade” by Karl James Anderson, NA (1874-1956), circa 1910-15, oil on canvas, unsigned, label on reverse and plate on frame. Private collection.

For the most part, they were already well-established professionals, Gunn Bromley said, who were making their living through their artwork. Manhattan was just a short train ride away on the New Haven Railroad or a reasonable journey by automobile.

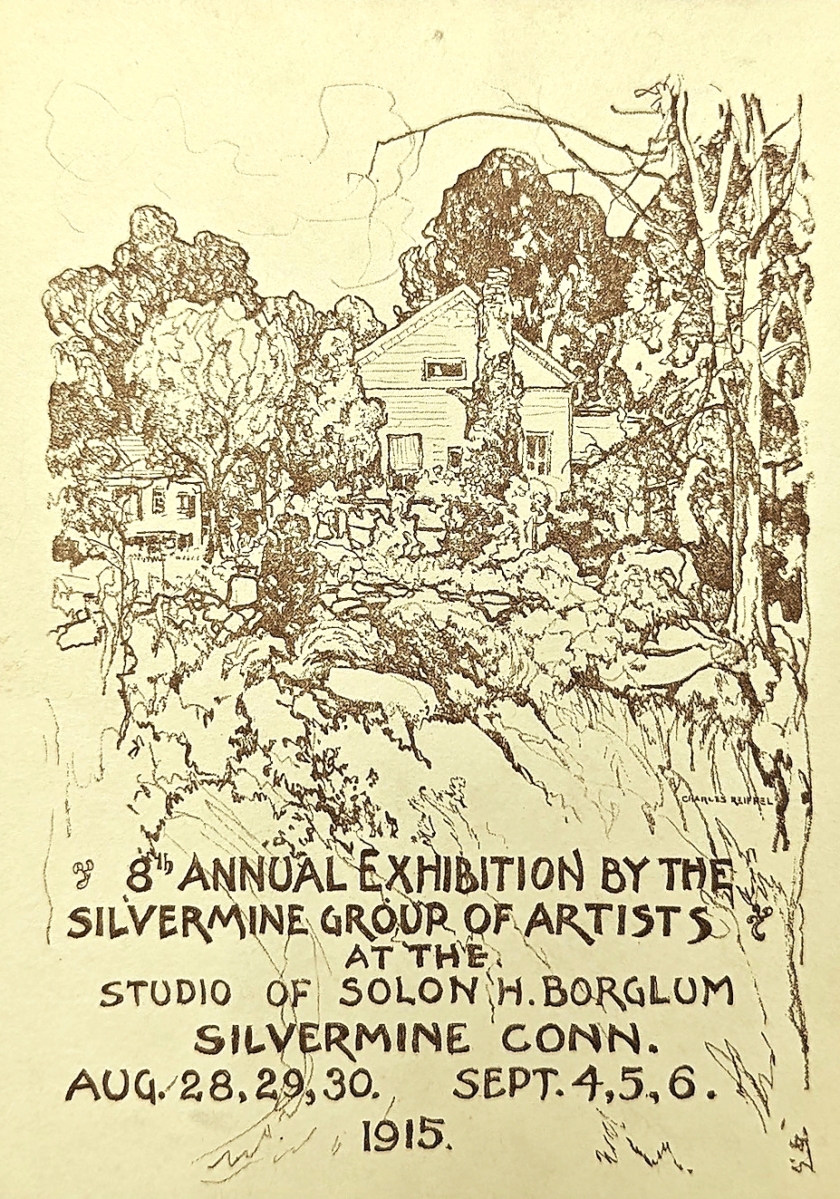

Borglum used the barn on his property for studio work in the colder months but, in 1908, offered it as a center for fellow artists to gather for Sunday morning critiques in the summer. The cadre of working creatives drafted formal rules for what became known as The Silvermine Group of Artists or The Silvermine Art Colony. Membership was open to accomplished working artists who agreed to participate in the weekly critiques and in the colony’s annual exhibitions.

“Almost immediately it was clear that these Silvermine newcomers wanted to be together – to draw inspiration from one another, to be part of the same intellectual community, and to share ideas,” Geary said.

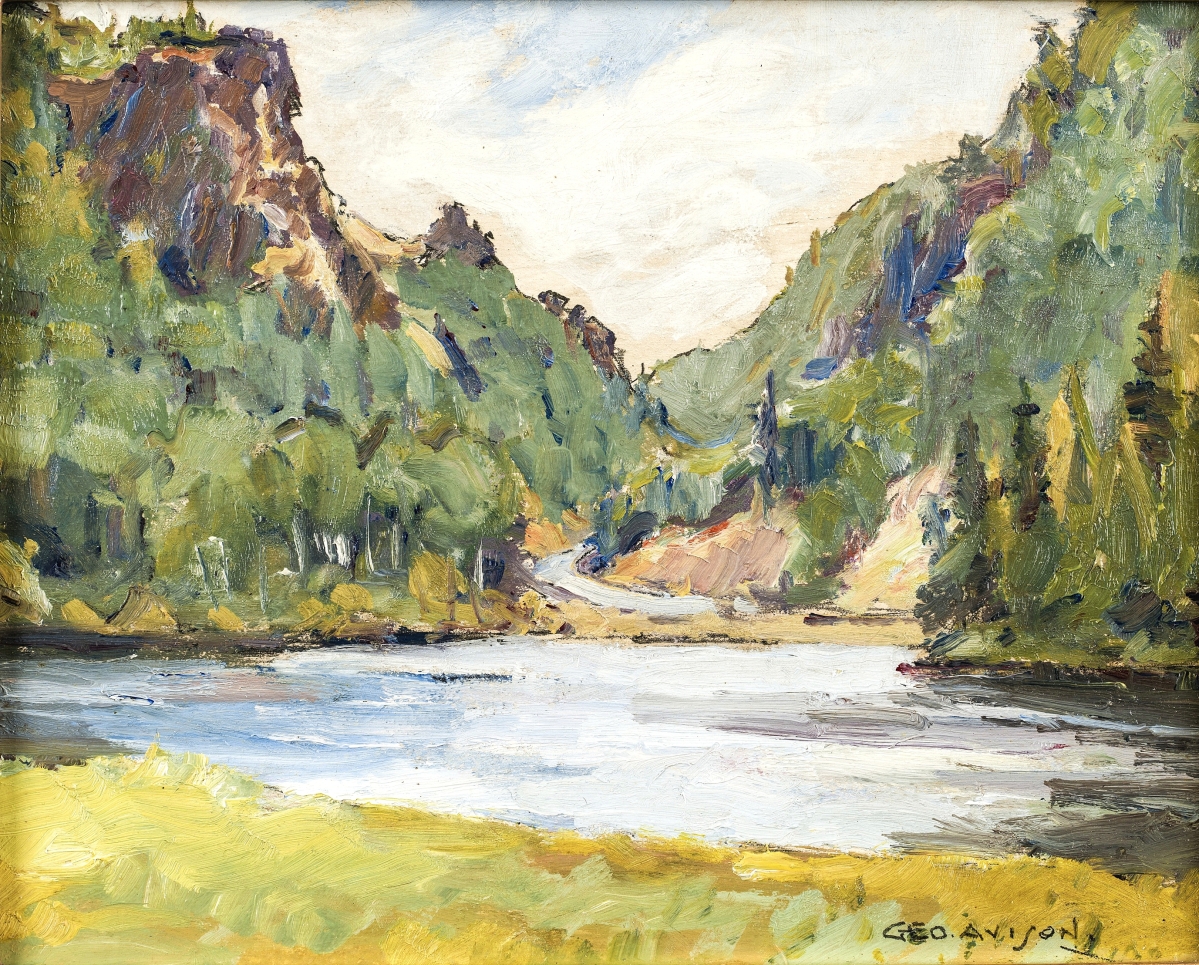

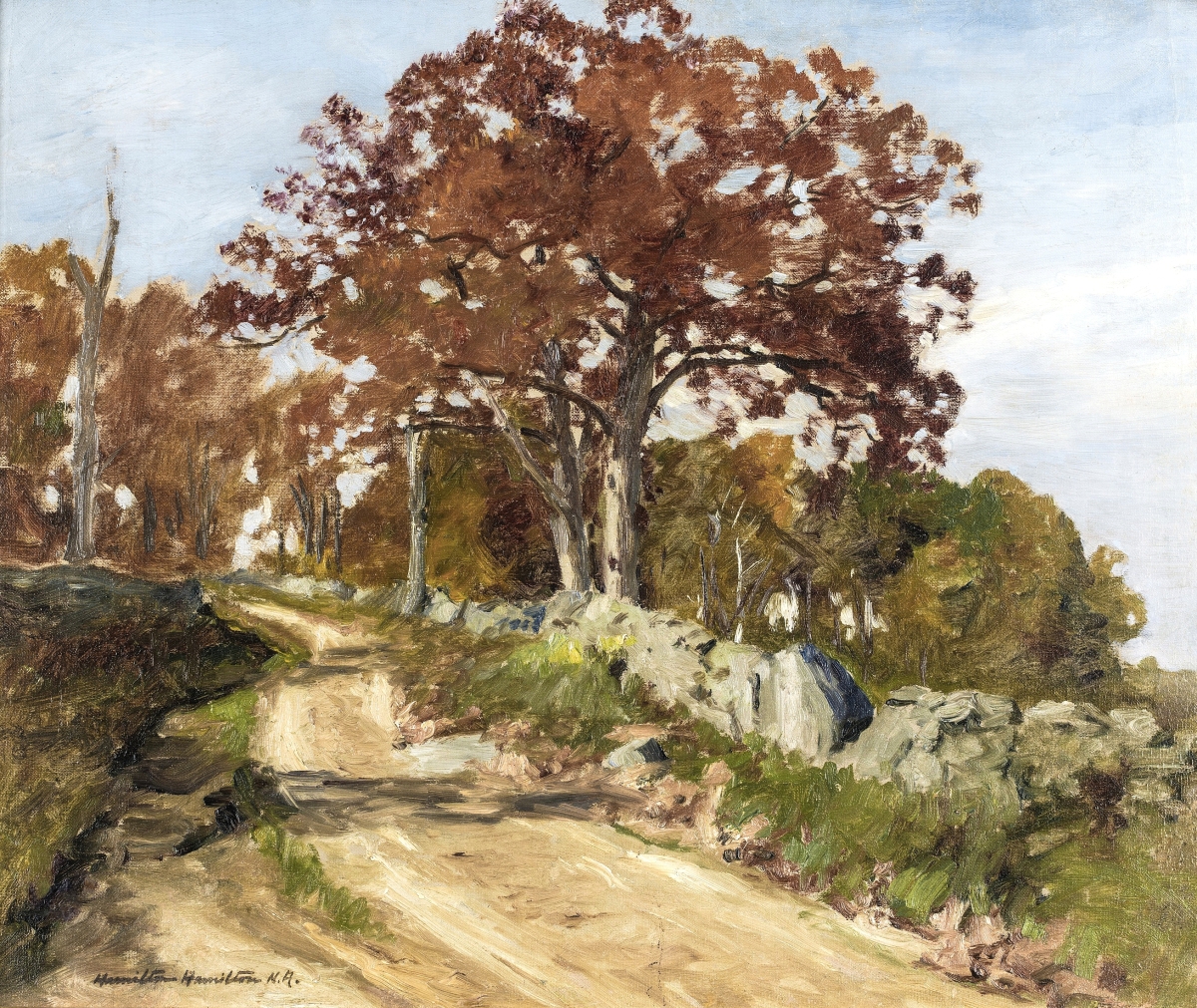

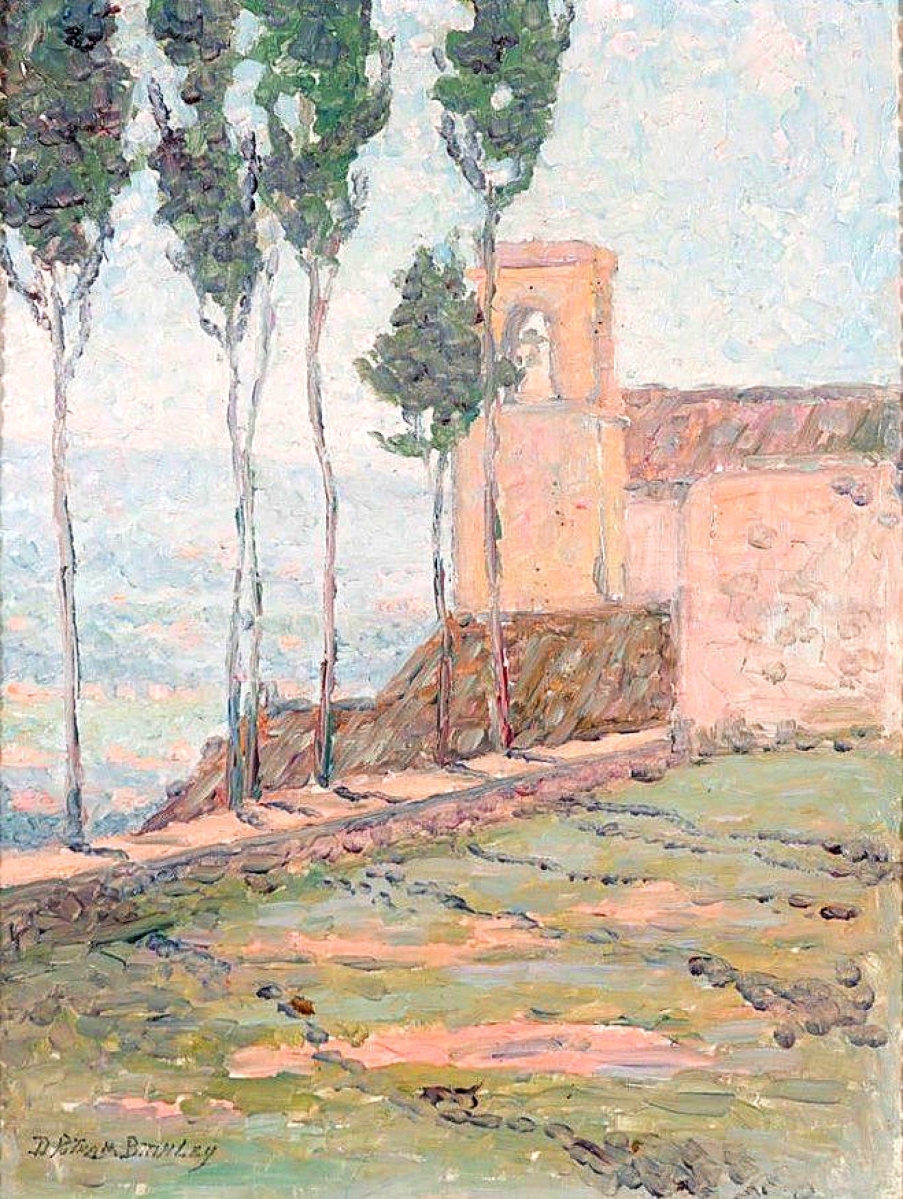

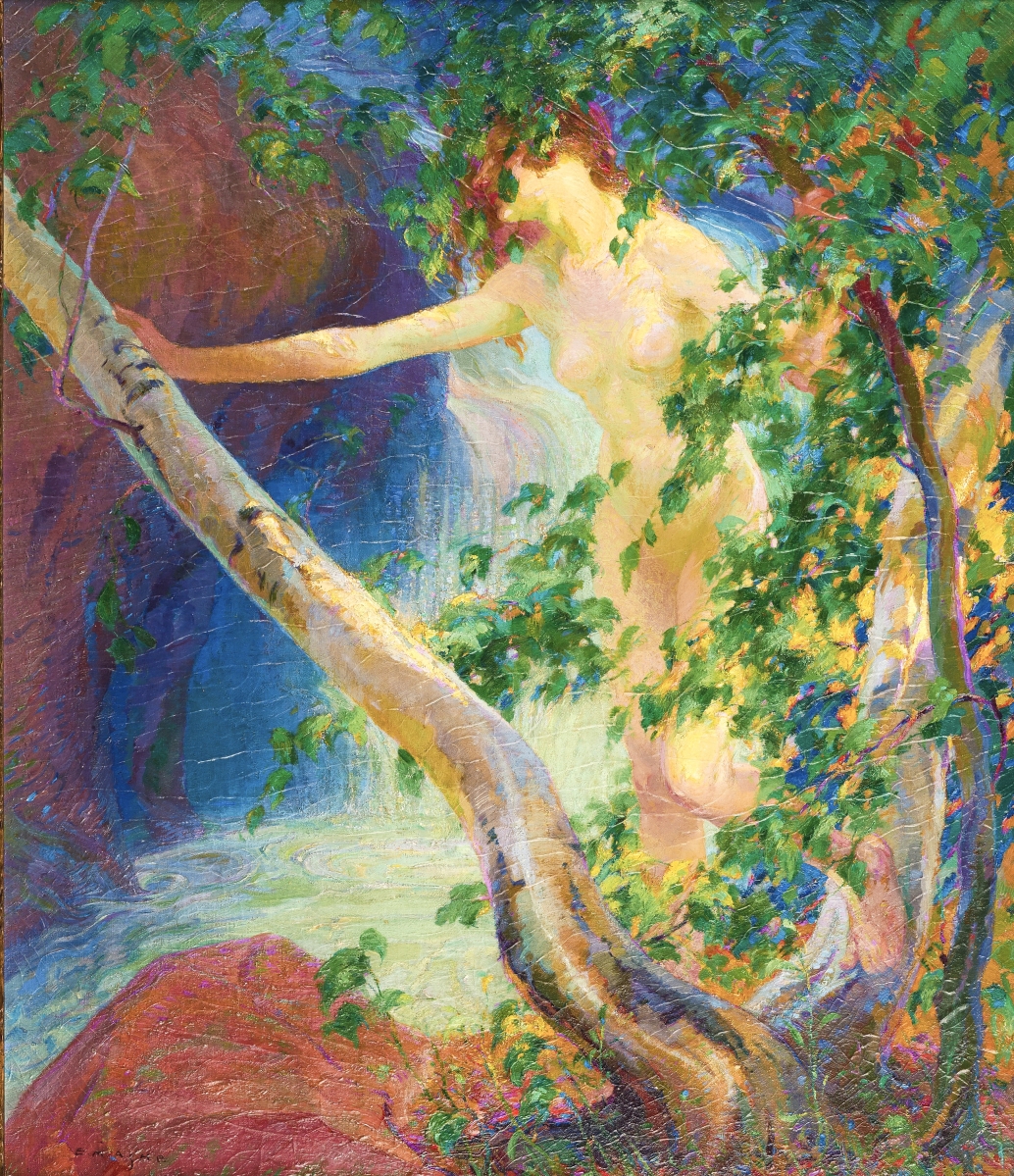

A steady influx led to other members, including Frank Townsend Hutchens (1869-1937), a successful portrait and landscape painter; D. Putnam Brinley (1879-1963) an impressionist and post-impressionist painter, muralist and early modernist; Hamilton Hamilton (1847-1928), a portrait and landscape artist; Leo F. Dorn (1879-1964) and Frederick C. Yohn (1875-1933), commercial illustrators who were in great demand; Richard Buckner Gruelle (1851-1914), a tonalist and Bernard Gutmann (1869-1936), the impressionist and post-impressionist painter, printmaker and illustrator.

“Autumn Morning” by Addison Thomas Millar (1860-1913), 1912, oil on canvas. New Canaan Museum & Historical Society.

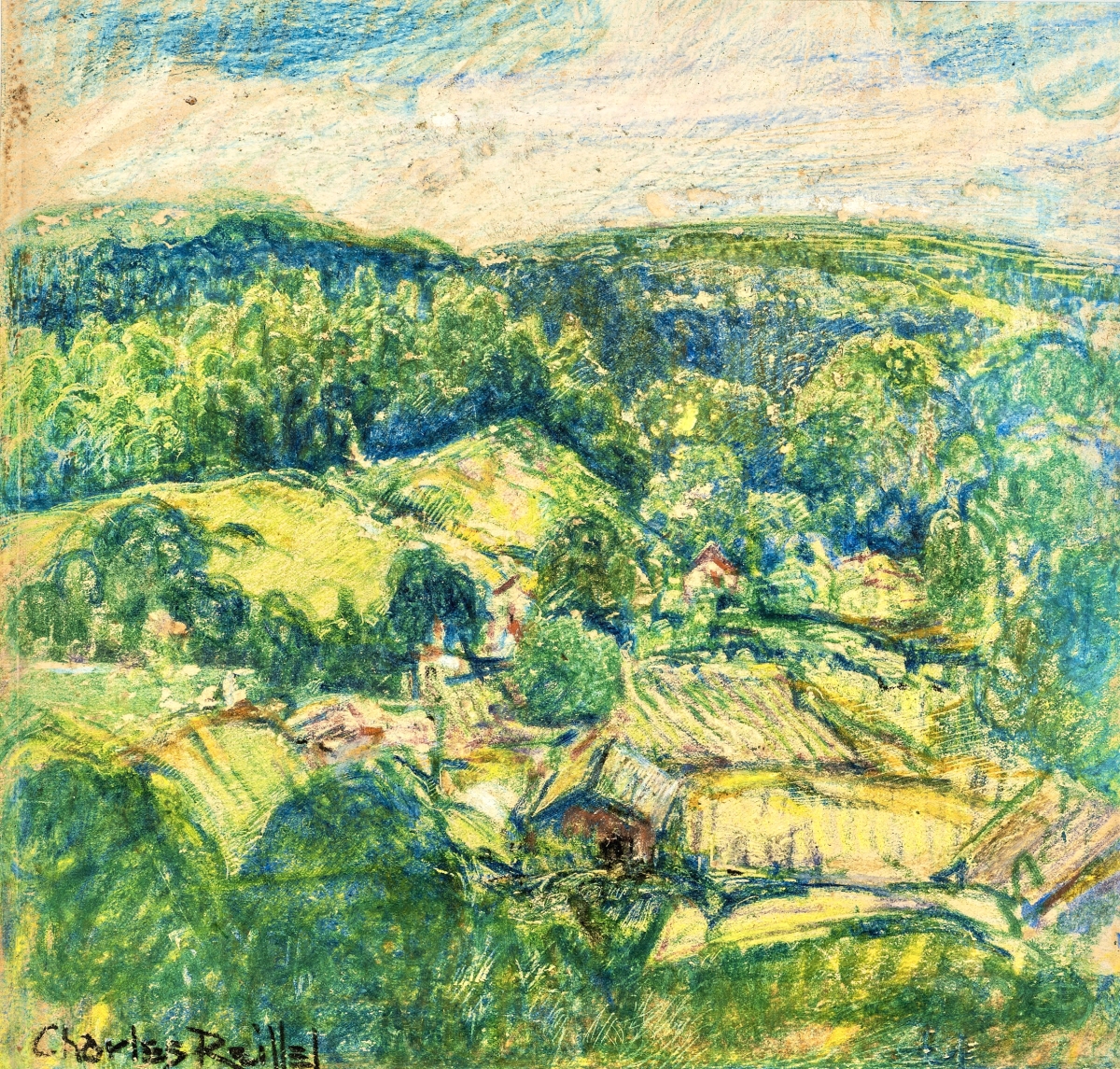

While most had studied and exhibited in Europe and worked in New York, they were absorbing and confronting the artistic crosscurrents of the day. New York had become the artistic epicenter of the United States, and Borglum and Brinley played significant roles in organizing the 1913 New York Armory Show. This exhibition introduced many Americans to European Modernism, Cubism and Abstraction. Silvermine members Borglum, Brinley, Ashe, Gutmann and Karl Anderson (1874-1956) all exhibited, and Guild members Helen Hamilton (1889-1970) and Charles Reiffel (1862-1942) appear to have become deeply inspired by their exposure to new ideas. Hamilton fell under the spell of Van Gogh’s post-impressionist painting, “The Weeders,” and worked almost exclusively for the rest of her life with a palette knife. Reiffel, already a highly accomplished commercial lithographer, produced a series of post-impressionist paintings that still feel bracingly modern.

The colony’s summer exhibitions proved immediately popular, garnering enthusiastic reviews from critics and large crowds of the curious during their duration. The printed invitations to these events were art in themselves, created by members who had backgrounds in lithography and graphic design.

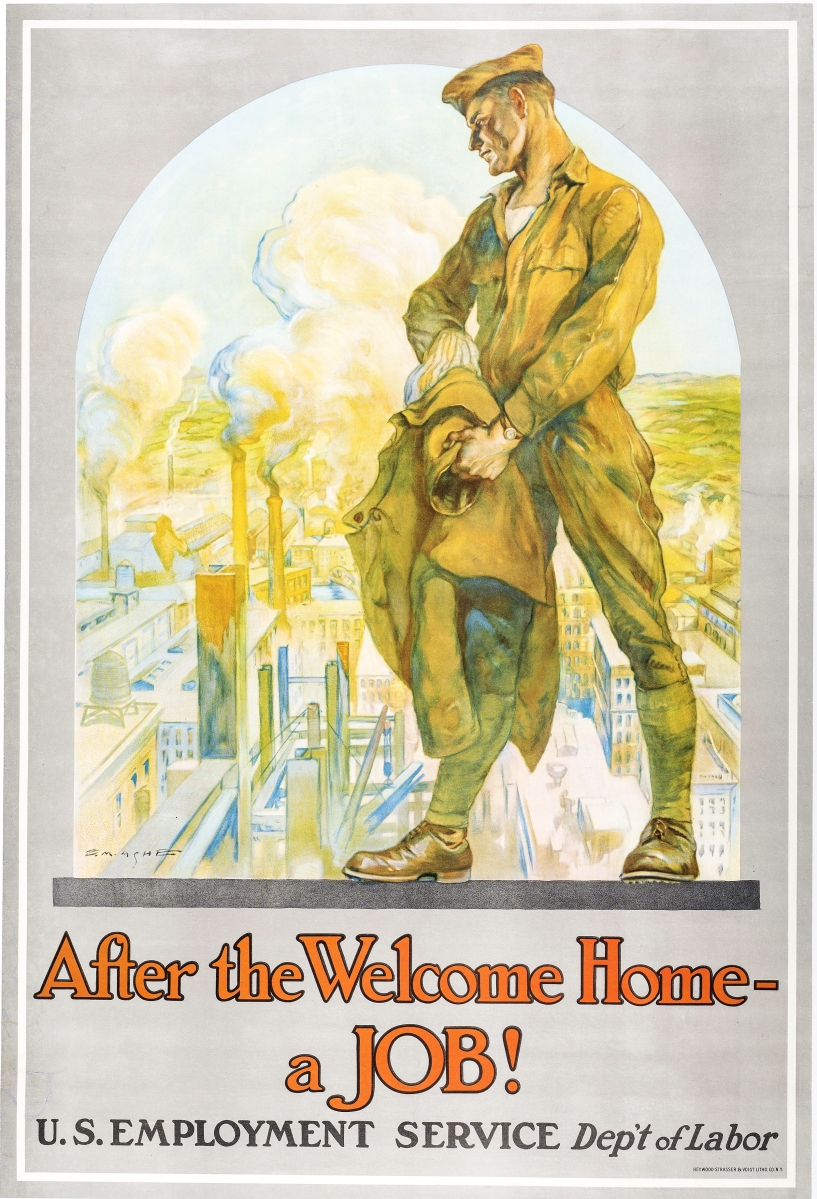

Soon historic events, namely World War I, altered the Colony’s trajectory, as a number of members dispersed to serve in the military or to offer aid abroad. Borglum and Brinley worked for the war effort in France, and Ashe and Yohn created posters. Others trained as machine gunners or worked in supply factories. The colony continued during the war but with reduced numbers.

In 1922, Borglum died suddenly from complications from appendicitis, and the colony lost its center. Its members had long been looking for larger exhibition space and room to expand their interests, and with the loss of Borglum’s studio, a new space was essential. They bought property with a large barn and incorporated as The Silvermine Guild of Artists that same year. Today, it remains the country’s longest-operating guild, with its membership contingent upon a selective peer jurying process. It continues to exert its influence in the Twenty-First Century, and claims a full roster of celebrated artists from Abe Ajay to James Grashow and Alice Neel as members.

“Evening” by Solon Hannibal Borglum, NSS, ANA (1868-1922), circa 1970, bronze with patina. New Canaan Museum & Historical Society.

Volmer became fascinated with the guild in 1997, when he bought a painting signed with the moniker of Silvermine Group of Artists. With his background in art, and through his work as a weekend antiques dealers alongside his wife, he suspected that he was on the cusp of a much larger story. Bromley, also with a background in fine art and history, then director and curator of the Norwalk Museum, increasingly felt that this was a significant, but little-known chapter in Connecticut’s art history. The two joined forces, and in the following years have scoured the country, seeking to learn where the wide range of works had landed. Bromley said that to this day, art historians are not generally aware of the importance of the Silvermine Colony, and its members and their work has been largely forgotten.

Volmer added that most people do not know how to differentiate the colony’s history with that of the Silvermine Center for the Arts, which runs year-round classes on its Silvermine campus and outreach programs in several of Connecticut’s inner cities.

“The Colony was all about self-improvement and showing their artwork, but not teaching summer classes in Silvermine,” Volmer said simply. But both he and Bromley are convinced the public will be astonished at the quality, beauty and variety of works that were produced by colony members.

Volmer and Bromley have taken pains to find choice examples by leading artists to show how their work changed. Millar’s “Silvermine, Fall Landscape,” a post-impressionist work, marks a significant departure from the detailed and carefully applied brush strokes of his revered Orientalist paintings. “Sunset at Compo Beach,” Hutchens’ Fauvist paean to the popular Westport, Conn., bathing beach, is painted in quick strokes with thin washes and splashes of impasto. In Helen Hamilton’s “Buttery Mill,” we see how she modified her painting style and application of color after encountering Vincent van Gogh’s work. There are many other strong pieces, including those by Anderson, Borglum, Brinley and Reiffel.

The exhibition has been installed in two separate galleries: a ground level devoted to prints and etchings, which is on view through February 4, and the upper gallery with 36 paintings, sculpture and pastels on loan from museums and private collections, continuing to April 30. Several lectures are also in the works, which Geary and the co-curators have planned for ongoing engagement.

Opening day of the Annual Silvermine Summer Exhibition, photographer unknown, 1909.

“I think the magic of the colony is much like the magic of the midcentury modern architecture community – a group with a shared passion who worked and socialized together and were able to be fueled by one another’s creativity,” Geary said, adding, “I think of the salons in Paris where writers such as Hemingway and Fitzgerald talked about life and work and art. Sadly, it’s a kind of collegiality missing for many today.”

“I don’t think people in New Canaan know that much about the group of Silvermine artists, which is too bad,” she added. “But perhaps this show and some of the publicity it receives will help with that.”

Significantly, Bromley, Volmer and Geary are immersed in plans for a dedicated study center and exhibition gallery that will be erected in a separate building on the museum’s grounds.

“The architect has almost finalized the designs and we will move to construction documents,” Geary says. “My guesstimate is that it will be completed in 18 months.” For once and for all, it would seem, the Silvermine Colony’s story is off and running.

A publication by Ed Volmer and Susan Gunn Bromley, The Silvermine Art Colony, The Silvermine Group of Artists 1908-1922 (The New Canaan Museum & Historical Society, 2022) accompanies the exhibition.

The New Canaan Museum & Historical Society is at 13 Oenoke Ridge. For information, 203-966-1776 or www.nhchistory.org.